Les Cahiers D'afrique De L'est / the East African Review, 38

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observing and Analysing Thé 1997 General Elections

Préface and acknowledgements xvii Nzibo, thé ftenyan ambassador. Prof. Kivutha Kibwana, chairman of the 1 National Convention Executive Council (NCEC) in Kenya, a platform for several gr&Hps in thé Kenyan society campaignmg for a review of the c<$nstitutiojj|l||,so attended, courtesy of HIVOS. Observing and Analysing thé 1997 în open-minded and stimulating environment, participants General Elections : An Introduction entfosiastQyy evaluated Kenyan politics and the élection observation, happy to sklp tea oreaks, to take a short lunch and continue till late. Draft chapters François Grignon, Marcel Ruiten, Alamin Mazrui , pfesented by thé authors were discussed and commented upon, the object being to provide a better understanding of the outcome of the Kenyan élections , -aad to explain the new model for élection observation. In addition, a scientific Kenya held ils first multi-party presidential and parliamentary élections since CQmimttee consisting of the editors and Charles Hornsby made detailed 1966 on 29 December 1992. It followed the footsteps of Zambia which, among commenta to each and every paper. iÉi: -$% * thé English-speaking African countries, had heralded thé transition from single pThf editors would, first and foremost, like to thank ail book contributors, to multi-party politics in October 1991 (Andreassen et al 1992). The road to disposants as well as participants during the conférence. Thèse include Paul thé institutionalisation of a pluralist political system after more than twenty Hapdow and David Throup who were not able to contribute to this volume. years of a de-facto (1969-82) and then a de-juré (1982-91) single-party system We would also like to acknowledge thé logistical support of the administrative had been a rocky one. -

Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 8 | Issue 2 Article 1 Spring 2010 Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Edwin Odhiambo Abuya, Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections?, 8 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 122 (2010). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol8/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2010 by Northwestern University School of Law Volume 8, Issue 2 (Spring 2010) Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Can African States Conduct Free and Fair Presidential Elections? Edwin Odhiambo Abuya* Asiyekubali kushindwa si msihindani.1 I. INTRODUCTION ¶1 Can African States hold free and fair elections? To put it another way, is it possible to conduct presidential elections in Africa that meet internationally recognized standards? These questions can be answered in the affirmative. However, in order to safeguard voting rights, specific reforms must be adopted and implemented on the ground. In keeping with international legal standards on democracy,2 the constitutions of many African states recognize the right to vote.3 This right is reflected in the fact that these states hold regular elections. The right to vote is fundamental in any democratic state, but an entitlement does not guarantee that right simply by providing for elections. -

The Social, Cultural and Economic Impact of Ethnic Violence in Molo Division, 1969 – 2008

THE SOCIAL, CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACT OF ETHNIC VIOLENCE IN MOLO DIVISION, 1969 – 2008. BY MUIRU PAUL NJOROGE REG. NO. C50/10046/2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY. NOVEMBER 2012 ii DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been submitted for a degree in any other university. ______________________Signature Date_______________ Muiru Paul Njoroge Department of History, Archaeology and Political Studies This thesis has been submitted for examination with our knowledge as university supervisors _____________________Signature Date____________________ Dr. Samson Moenga Omwoyo Department of History, Archaeology and Politics Studies ___________________Signature Date____________________ Dr. Peter Wafula Wekesa Department of History, Archaeology and Political Studies iii DEDICATION To my parents, Salome Wanjiru and James Muiru, my brothers and sisters as well was my dear wife, Sharon Chemutai. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study would not have been possible without the assistance of several people and institutions. My gratitude first goes to Kenyatta University for awarding me a postgraduate scholarship, and to colleagues at Naivasha Day Secondary School for their moral support. I am eternally indebted to my supervisors Dr Peter Wekesa Wafula and Dr. Samson Moenga Omwoyo who spared no efforts to iniate me into the world of scholarship. I would also like to thank all members of the Department of History, Archaeology and Political Studies for their academic guidance since my undergraduate days (1998-2002). I cannot forget to thank the staff of the Post Modern Library of Kenyatta University, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Library of Egerton University for their assistance in the course of writing this work. -

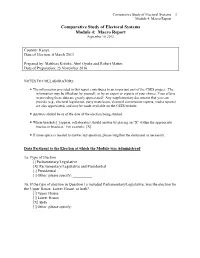

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 4: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012 Country: Kenya Date of Election: 4 March 2013 Prepared by: Matthias Krönke, Abel Oyuke and Robert Mattes Date of Preparation: 23 November 2016 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: . The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] . If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [] Parliamentary/Legislative [X] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [ ] Lower House [X] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 4: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election, regardless of whether the election was presidential? Party of National Unity and Allies (National Rainbow Coalition) 2b. -

Les Cahiers D'afrique De L'est / the East African Review, 38

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 38 | 2008 The General Elections in Kenya, 2007 Special Issue Bernard Calas (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/644 Publisher IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Printed version Date of publication: 1 April 2008 ISSN: 2071-7245 Electronic reference Bernard Calas (dir.), Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review, 38 | 2008, « The General Elections in Kenya, 2007 » [Online], Online since 17 July 2019, connection on 07 February 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/644 This text was automatically generated on 7 February 2020. Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 1 EDITOR'S NOTE This issue, published in 2008, was revised and corrected in 2019. Ce numéro, publié en 2008, a été révisé et corrigé en 2019. Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review, 38 | 2008 2 Introduction Jérôme Lafargue 1 This book is a translation of a special issue of IFRA’s journal Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est, no. 37, and of a collection of articles from Politique africaine, no. 109. These both focused on the General Elections in Kenya at the end of 2007. The on-site presence of several researchers (Bernard Calas, Anne Cussac, Dominique Connan, Musambayi Katumanga, Jérôme Lafargue, Patrick Mutahi), fieldwork carried out by others between December 2007 and February 2008 (Florence Brisset-Foucault, Ronan Porhel, Brice Rambaud), as well as a good knowledge of the country by researchers on regular visits (Claire Médard, Hervé Maupeu), were all ingredients that led to the production of hundreds of pages within a limited period. -

Electoral Challenges Encountered by Women Aspirants in Kericho And

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 5, May-2018 ISSN 2229-5518 1,461 Electoral Challenges Encountered by Women Aspirants in Kericho and Bomet Counties during Elections Campaigns in Kenya By Kathryn Chepkemoi Langat Department of Social Work & Criminology Kibabii University P, O Box 1699-50200 Bungoma This study focused on electoral process and conflicts encountered by women aspirants in Kericho and Bomet counties during electioneering period in Kenya. Past studies indicates that women candidates in the world face many hurdles during electioneering period and Sub-Sahara Africa has been leading on elections offenses meted on women followed by Asian countries. It was as a result of this that the studies on women participation in elections drew the attention of United Nations and various treaties were signed to give women a level ground to express their political right by contesting like men. However, the Kenya politics even after promulgation of 2010 constitution elective positions is still domineered by men. The purpose of this study was to explore electoral challenges encountered by women aspirants during elections campaign period in Kenya. The study areas was Bomet and Kericho County. The study was guided by patriarchal theory. The literature was reviewed from global perspective, Africa and Kenya context. The study adopted both qualitative and quantitative research method which was suitable in collecting opinions of the electorates. The target population comprised of 4,000 registered voters in Bomet and Kericho Counties. A sample of 10% of the target population yielded 400 sample sizes. Simple random sampling was used to obtain 200 respondents from each county. -

Bomet Constituency 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface…………………………………………………………………….. i 1. District Context………………………………………………………… 1 1.1. Demographic characteristics………………………………….. 1 1.2. Socio-economic Profile………………………………………….. 1 2. Constituency Profile………………………………………………….. 1 2.1. Demographic characteristics………………………………….. 1 2.2. Socio-economic Profile………………………………………….. 1 2.3. Electioneering and Political Information……………………. 2 2.4. 1992 Election Results…………………………………………… 2 2.5. 1997 Election Results…………………………………………… 2 2.6. Main problems……………………………………………………. 2 3. Constitution Making/Review Process…………………………… 3 3.1. Constituency Constitutional Forums (CCFs)………………. 3 3.2. District Coordinators……………………………………………. 5 4. Civic Education………………………………………………………… 6 4.1. Phases covered in Civic Education…………………………… 6 4.2. Issues and Areas Covered……………………………………… 6 5. Constituency Public Hearings……………………………………… 7 5.1. Logistical Details…………………………………………………. 5.2. Attendants Details……………………………………………….. 7 5.3. Concerns and Recommendations…………………………….. 7 8 Appendices 31 1. DISTRICT CONTEXT Bomet is a constituency in Bomet District. Bomet District is one of 18 districts of the Rift Valley Province of Kenya. 1.1. Demographic Characteristics Male Female Total District Population by Sex 185,999 196,795 382,794 Total District Population Aged 18 years & 117,124 115,106 232,230 Below Total District Population Aged Above 18 68,875 81,689 150,564 years Population Density (persons/Km2) 203 1.2. Socio-Economic Profile Bomet District: • Is the 4th most densely populated district in the province; • Has -

Hezron Ndunde.Pdf

CODESRIA 12th General Assembly Governing the African Public Sphere 12e Assemblée générale Administrer l’espace public africain 12a Assembleia Geral Governar o Espaço Público Africano ةيعمجلا ةيمومعلا ةيناثلا رشع ﺣﻜﻢ اﻟﻔﻀﺎء اﻟﻌﺎم اﻹﻓﺮﻳﻘﻰ From Cyberspace to the Public: Rumor, Gossip and Hearsay in the Paradoxes of the 2007 General Election in Kenya Hezron Ndunde Egerton University 07-11/12/2008 Yaoundé, Cameroun Abstract While political control, draconian press laws, selective communication and downright misinformation and disinformation by the state took centre stage in the wake of post-election violence in Kenya, the citizens had to seek alternative ways of satisfying their information and communication needs. Among these alternative ways were what Spultunik terms as “small media” such as graffiti, flyers, underground cassettes, internet listservs, slogans, jokes and rumors which despite being rather diffuse and not direct in their engagement with the state and global structures of repression, nevertheless, served as vital and pervasive undercurrent and reservoirs of political commentary, critique and potential mobilization. Out of thousands of such encounters, "public opinion" slowly formed and became the context in which politics was framed. Cyberspace was easily adapted and embraced as an essential aspect of resistance struggles, beginning with news forums, interactive websites, and/or personal weblogs (blogs). Electronic communication, whether via computers, wireless PDAs, or text messages between cell phones, created new forms of relatively facile information transmission, communication, coordination, and connections between social actors that in turn enabled new kinds of social mobilizations not tied to specific locales. Anyone anywhere having access to a terminal, or even a handheld phone or PDAs with Internet capability could provide information to anyone else as often as events took place. -

AC Vol 42 No 18

www.africa-confidential.com 14 September 2001 Vol 42 No 18 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL ZAMBIA 3 KENYA Puppet or prince? Levy Mwanawasa’s emergence as Moi versus the economy MMD’s flagbearer is the least bad Galloping inflation, sinking export prices and corruption are bigger option for President Chiluba. problems for the President than the opposition Having abandoned his tilt at a third term, Chiluba finds a malleable President Daniel arap Moi has run out of promises. The Board of the International Monetary Fund candidate and a way to hold on to refuses to unblock further loans – in particular, a hoped for quick credit of US$125 million. This is executive power. Oppositionists suspended until Moi’s ruling Kenya African National Union steers an effective anti-corruption bill are buoyed by the prospect of more through parliament, and sells off the state telecommunications company and Kenya Commercial Bank. infighting in the ruling MMD. Opposition parliamentarians threw out an anti-corruption bill last month and a revised bill can hardly be passed before early next year. Any IMF help will come too late to rescue the economy before the elections SEYCHELLES 4 that are scheduled for December 2002. The economy now hangs on tea. Coffee and tourism, once big foreign-exchange earners, lose millions By a whisker of dollars to official rake-offs. State-owned companies are mired in bureaucracy and corruption. After a tight presidential race, Business is pessimistic, domestic debt is swelling, public services are among the world’s worst and Albert René will find it tough to win officials are among the most corrupt. -

KLB Is Born Pioneers, Leaders and Workers

October 2020 KLB is Born Pioneers, Leaders and Workers ONLINE EDITION www.klb.co.ke Inside this issue.... 2 Editorial 3 MD's Note 4 KLB set to unveil new Strategic Plan 5 Gazing Ahead: Our promise to stakeholders 8 KLB is Born: Pioneers, Leaders and Workers 13 KLB Captains EDITORIAL TEAM Managing Editor: Diana Olenja OUR VISION WE WILL Editor: Joseph Ndegwa A knowledgeable and inspired society Design and Layout: Sylvester Karanja • Comply with regulatory and statutory requirements. Photography: Joseph Ndegwa, Bernard MISSION STATEMENT Kibui and Ronald • Continually improve the effectiveness of our To provide innovative and competitive Kibaron publishing and printing solutions. Management Systems. Contributions: Joseph Ndegwa, Diana • Achieve and ensure that our customers Olenja Ronald Kibaron OUR CORE VALUES receive the highest quality service. • Customer Focus and Sharon Nderema • Integrity • As a team, be guided by strict adherence • Creativity and Innovation to laid down procedures and strive to be • Quality Publishing and Printing Solutions competitive and independent; and will protect and uphold our customers’ interest without compromising the quality standards OUR QUALITY POLICY set. Kenya Literature Bureau is committed to and shall always endeavour to reach the highest Our quality objectives shall be established and reviewed at the regular management review meetings. level of quality in publishing and printing Published by: All correspondence to the: KENYA LITERATURE BUREAU Corporate Communications Office, educational and knowledge materials as P.O. Box 30022-00100, Nairobi P. O. Box 30022 - 00100, Nairobi. stipulated by the ISO 9001 : 2015 Quality KLB Road, Off Popo Road, Belle-vue Area, South C Tel: 254 20 3541196/7, 0711 318 188 Tel:+254203541196/7, 0711318188 Management System. -

Electoral Geography and Conflict

Electoral Geography and Conflict: Examining the Redistricting through Violence in Kenya Kimuli Kasara Columbia University∗ March 2016 Abstract Politicians may use violence to alter the composition of the electorate either by suppressing turnout or by permanently displacing voters. This paper argues that politicians are more likely to use violent redistricting where it can sway electoral results and when their opponents sup- porters are less likely to return if displaced by violence. I explore the relationship between electoral geography and violence in Kenya’s Rift Valley Province during the crisis that fol- lowed Kenya’s disputed 2007 general election. Using the proportion of migrants in a neigh- borhood as one proxy for residents’ propensity to relocate, I show that more violence occurred in electorally pivotal localities as well as in localities that were both electorally pivotal and contained more migrants. ∗Address: Department of Political Science, Columbia University, International Affairs Building, 420 W. 118th Street, New York, NY 10027, [email protected]. I thank Kate Baldwin, Joel Barkan, Rikhil Bhavnani, Luke Condra, Catherine Duggan, Thad Dunning, Lucy Goodhart, Jim Fearon, Macartan Humphreys, Saumitra Jha, Jackie Klopp, Jeffrey Lax, Peter Lorentzen, Gerard Padro ´ı Miquel, Kenneth McElwain, Stephen Ndegwa, Jonathan Rodden, Jack Snyder and seminar participants at the Yale and NYU for comments on a previous draft of this paper. Ayla Bonfiglio, Benjamin Clark, and Kate Redburn provided excellent research assistance. The Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy at Columbia University and the Hoover Institution at Stanford University provided research support. All mistakes are my own. 1 Introduction Elections are associated with conflict in several new democracies. -

Le Kenya D'une Élection À L'autre Criminalisation De L'etat Et Succession Politique (1995-1997)

L e s É t u d e s d u C E R I N° 35 - décembre 1997 Le Kenya d'une élection à l'autre Criminalisation de l'Etat et succession politique (1995-1997) Chris Thomas Centre d'études et de recherches internationales Fondation nationale des sciences politiques Le Kenya d'une élection à l'autre Criminalisation de l'Etat et succession politique (1995-1997) Chris Thomas Jusqu'au début des années quatre-vingt, le Kenya était réputé pour sa stabilité politique. Daniel arap Moi a ainsi succédé à Jomo Kenyatta en 1978 dans le respect le plus strict des règles constitutionnelles du pays. Mais une tentative de coup d'Etat est venue en 1982 briser l'image exotique et rassurante de ce pays touristique. Les populations urbaines ont fait irruption sur la scène politique nationale, révélant par ailleurs la violence des nationalismes ethniques. La compétition pour le pouvoir, que Jomo Kenyatta parvenait à réguler en faisant preuve d'une poigne de fer adoucie par le partage des ressources nationales, était devenue une véritable lutte, maîtrisée par Daniel arap Moi au prix d'une évolution autoritaire brutale de son régime. Tout au long des années quatre-vingt, avec l'accroissement des difficultés économiques du pays et la mise en place des premières mesures d'ajustement structurel, la base sociale élargie sur laquelle reposait le pouvoir présidentiel en 1978 s'est réduite comme une peau de chagrin, à mesure que le partage des ressources du pays se faisait plus étroit et que croissaient l'autoritarisme et la répression politique de toute forme de contestation.