Matilda of Canossa Has for Some Time Been a Figure of Extensive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impianti Di Distribuzione/Punti Di Consegna Reggio Emilia

Dati identificativi impianti distribuzione/Comuni/REMI gas naturale IMPIANTO DI PRESSIONE GAS CODICE IMPIANTO COMUNE/PORZIONE DENOMINAZIONE DISTRIBUZIONE DENOMINAZIONE IMPIANTO CODICE REMI CODICE REMI PUNTI DI NOME IMPRESA DISTRIBUZIONE COMUNE SERVITO DA REMI /CENTRALE INTERCONNESSO DISTRIBUZIONE (AEEGSI) AGGREGATO (Punto di riconsegna) CONSEGNA FISICI DI TRSPORTO (Codice univoco AEEGSI) IMPIANTO DISTRIBUZIONE GPL CON ALTRI (bar minimo) IMPIANTI AREAAREA REGGIO PARMA EMILIA ALBINEA 34618502 ALBINEA BIBBIANO 34618501 QUATTRO CASTELLA QUATTRO CASTELLA 34618503 RIVALTA ALBINEA - QUATTRO CASTELLA 2PCSM17 34618500 14 NO SNAM RETE GAS REGGIO EMILIA SCANDIANO VEZZANO SUL CROSTOLO BAISO BUSANA CANOSSA CARPINETI CASINA CASTELNOVO NE' MONTI SI (HERA BAISO-PULPIANO 2PCSM19 NEVIANO DEGLI ARDUINI 34624200 34615801 PULPIANO 8,5 SNAM RETE GAS BOLOGNA) RAMISETO TOANO VETTO VEZZANO SUL CROSTOLO VIANO VILLA MINOZZO BIBBIANO BIBBIANO 2PCSM20 QUATTRO CASTELLA 34615901 34615901 BIBBIANO 26 NO SNAM RETE GAS SAN POLO D'ENZA BORETTO BORETTO 2PCSM21 BRESCELLO 34616001 34616001 BORETTO 13 NO SNAM RETE GAS POVIGLIO BRESCELLO - LENTIGIONE 2PCSM22 BRESCELLO 34616102 34616102 LENTIGIONE 27 NO SNAM RETE GAS BRESCELLO - CAPOLUOGO 2PCSM23 BRESCELLO 34616103 34616103 BRESCELLO 14 NO SNAM RETE GAS CADELBOSCO DI SOPRA CADELBOSCO SOPRA 2PCSM24 34616301 34616301 CADELBOSCO SOPRA 12 NO SNAM RETE GAS REGGIO EMILIA CAMPAGNOLA EMILIA 2PCSM25 CAMPAGNOLA EMILIA 34616401 34616401 CAMPAGNOLA 27 NO SNAM RETE GAS CAMPEGINE 34617704 GATTATICO CASTELNOVO DI SOTTO 34617702 S.ILARIO S. -

Aperture Provincia Novembre

...and its Province!!! Monday Antonio Ligabue Museum (Gualtieri): 9.30-12.30 and 15.30-18.30 Estense Fortress (Montecchio Emilia): 9.00-13.00 and 15.00-18.00 Inlay work Museum (Rolo): 9.00-12.30 and 15.00-17.00 Tuesday Wednesday Peppone e Don Camillo Museum (Brescello): 9.30-12.30 and 14.30-17.30 Peppone e Don Camillo Museum (Brescello): 9.30-12.30 and 14.30-17.30 Guareschi Museum (Brescello): 9.30-12.30 and 14.30-17.30 Guareschi Museum (Brescello): 9.30-12.30 and 14.30-17.30 Cervi Brothers' home Museum (Gattatico): 10.00-13.00 Canossa Castle (Canossa): 9.00-13.00 e 13.30-16.30 Estense Fortress (Montecchio Emilia): 15.00-18.00 Cervi Brothers' home Museum (Gattatico): 10.00-13.00 Inlay work Museum (Rolo): 9.00-12.30 and 15.00-17.00 Antonio Ligabue Museum (Gualtieri): 9.30-12.30 and 15.30-18.30 Museum of the Terramara (Poviglio): 9.00-12.30 and 15.00-18.15 Estense Fortress (Montecchio Emilia): 9.00-13.00 Museum of the Terramara (Poviglio): 9.00-12.30 Thursday Friday Peppone e D.Camillo Museum(Brescello): 9.30-12.30 and 14.30-17.30 Bridge attendants Museum (Boretto): 9.00-12.00 and 15.00-18.00 Guareschi Museum (Brescello): 9.30-12.30 and 14.30-17.30 Peppone e Don Camillo Museum (Brescello): 9.30-12.30 and 14.30-17.30 Canossa Castle (Canossa): 9.00-13.00 e 13.30-16.30 Guareschi Museum (Brescello): 9.30-12.30 and 14.30-17.30 Sarzano Castle (Casina): 10.00-sunset Canossa Castle (Canossa): 9.00-13.00 e 13.30-16.30 Cervi Brothers' home Museum (Gattatico): 10.00-13.00 Cervi Brothers' home Museum (Gattatico): 10.00-13.00 Antonio Ligabue Museum -

SEZIONE LOCALE – BIBLIOGRAFIA GENERALE SU BRESCELLO Fonti Storiche, Pubblicazioni, Libri, Estratti, Documenti (2017)

SEZIONE LOCALE – BIBLIOGRAFIA GENERALE SU BRESCELLO Fonti storiche, pubblicazioni, libri, estratti, documenti (2017) NB. In colore rosso: ultimi inserimenti ALDONI EZIO, GORI GIANFRANCO MIRO, SETTI ANDREA, Amici Nemici : Brescello, piccolo mondo di celluloide, Brescello, Tipo-lito Valpadana, 2007 ALDONI EZIO, Amici nemici [DVD] : Brescello e i film di Peppone e Don Camillo raccontati dai protagonisti, Brescello, Studio Digit Sas, 2008. - 1 DVD (ca. 45 min.) : color., son. ; in contenitore, 19 cm. Antonio Panizzi. 1797 – 1879. Mostra documentaria, a cura di Maurizio Festanti, Comune di Reggio Emilia, Biblioteca Municipale "Panizzi", Istituto per i Beni Artistici, Culturali e Naturali della Regione Emilia-Romagna, Università degli Studi di Parma, con il patrocinio del Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali; in collaborazione con l'Amministrazione Provinciale di Reggio Emilia e la British Library di Londra, Reggio Emilia, 1979. ARMELLINI LUIGI MARIA, Incontro con S.Genesio. Atti e memorie 106 (2001/03). Estratto, Ancona, Deputazione di Storia Patria per le Marche, 2008 ASCARI SILVIA, La centuriazione, in Quaderni 6. Il paesaggio argrario italiano protostorico e antico. Storia e didattica. Summer School Emilio Sereni I Edizione 26-30 Agosto 2009 (atti), Gattatico, Edizioni Istituto Alcide Cervi, 2009 BACCHI FERDINANDO, CAGNOLATI GALLIANO, Marius Nizolius. 1488 – 1566, Modena, 1988. BALLESTRI MASSIMILIANO, Famiglia Cantoni di Poviglio e Brescello, s.l., 1990 BALLESTRI MASSIMILIANO, Mario Nizolio. 1488 – 1566, Milano, 1985. BELLOCCHI UGO, Antonio Panizzi (1979 – 1879). Principe dei bibliotecari, in "Circolo Filatelico Numismatico Reggiano – 14° Convegno Nazionale e Mostra Filatelico-Numismatica.", Reggio Emilia, 6-7 ottobre 1979, Reggio Emilia, 1979. BERNARD FRANCESCA, L'architettura di Piazza Matteotti a Brescello, Tesi di Laurea, Corso di Analisi della Morfologia Urbana e della Tipologia Edilizia, Professor Aldo De Poli, Data di consegna 24.01.2002, fotocopia. -

Ciano D’Enza Amm

Il Sindaco Mirca Carletti L’Assessore all’Urbanistica Daniele Caminati Il Segretario Comunale Maria Stefanini Gruppo di Progettazione: Arch. Ana de Balbin Ing. Monia Ruffini: Geom. Silvia Fallace Valutazione Ambientale di Sostenibilità Dott.sa Tania Tellini Dott. Stefano Baroni 2° PIANO OPERATIVO COMUNALE ADOZIONE APPROVAZIONE DELIBERA C.C. DELIBERA C.C. n° 12 del 26.03.2013 n° del REGIONE EMILIA ROMAGNA PROVINCIA DI REGGIO EMILIA COMUNE DI CANOSSA ANALISI AZIONE SISMICA PER IL PROGETTO DEFINITIVO DELLA VARIANTE ALLA SP 513R, TRATTO DI SAN POLO-RIO VICO-VIA CARBONIZZO (RE) AMMINISTRAZIONE PROVINCIALE DI REGGIO EMILIA INDICE INTRODUZIONE ...................................................................................................................................................................................................1 INQUADRAMENTO TOPOGRAFICO........................................................................................................................................................................1 CARATTERIZZAZIONE E MODELLAZIONE GEOLOGICA..........................................................................................................................................2 Serie litostratigrafica .....................................................................................................................................................................................4 INQUADRAMENTO SISMOTETTONICO ..................................................................................................................................................................7 -

11 Febbraio 2021

COVID-19, resoconto giornaliero 11-2-2021 In provincia di Reggio Emilia, su 142 nuovi casi positivi, 66 sono riconducibili a focolai, 76 classificati come sporadici. 139 casi sono in isolamento domiciliare, 2 pazienti ricoverati in terapia non intensiva, 1 paziente ricoverato in terapia intensiva. Nella giornata di ieri sono state vaccinate 399 persone mentre per quella odierna ne erano programmate 460. NUOVI CASI TOTALE TAMPONI POSITIVI 142 30 378 TERAPIA INTENSIVA 1 20 ISOLAMENTO DOMICILIARE 139 3565 RICOVERO NON INTENSIVA 2 168 * GUARITI CLINICAMENTE TOTALI 510 GUARITI CON TAMPONE NEGATIVO 25748 * Il dato comprende le persone positive in isolamento negli alberghi COVID Nuovi casi Albinea 1 Bagnolo in Piano 1 Baiso 5 Bibbiano 6 Boretto Brescello Cadelbosco Sopra 2 Campagnola Emilia 1 Campegine 2 Canossa Carpineti Casalgrande 3 Casina Castellarano 5 Castelnovo Sotto 6 Castelnovo ne’ Monti Cavriago Correggio 3 Fabbrico 1 Gattatico 2 Gualtieri 5 Guastalla 1 Luzzara 3 Montecchio Emilia 1 Novellara 9 Poviglio 1 Quattro Castella 2 Reggio Emilia 40 Reggiolo Rio Saliceto 2 Rolo 3 Rubiera 2 San Martino in Rio San Polo d’Enza 3 Sant’Ilario d’Enza 4 Scandiano 12 Toano Ventasso Vetto Vezzano sul Crostolo Viano 1 Villa Minozzo 6 Non residenti in provincia 1 Residenti in altra regione 8 Totale 142 Deceduti all’ 11 febbraio 2021: Oggi comunichiamo 9 decessi - Donne: 1924 n.1 – 1927 n.1 – 1929 n.1 -1935 n.1 -1936 n.1 - Uomini: 1935 n.1 – 1939 n.1 – 1941 n.1 – 1951 n.1 Deceduti Comune di residenza Parziale Totale Albinea 10 Bagnolo in Piano 10 Baiso -

Matilda of Canossa Has for Some Time Been A

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Journal of Medieval History on 30 September 2015, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03044181.2015.1089311 0 Reconsidering Donizone’s Vita Mathildis: Boniface of Canossa and Emperor Henry II Robert Houghton* Department of History, Medecroft Building, King Alfred Campus, Sparkford Road, Winchester, SO22 4NR, United Kingdom (Received 6 March 2014; final version received 5 November 2014) Boniface of Canossa is a figure of great importance to the political and military history of eleventh-century Italy. Modern historiography has almost universally argued that Boniface gained his power through a close relationship and alliance with a series of German emperors. Most accounts see Boniface’s fall and eventual murder in 1052 as a direct consequence of the breakdown of this relationship. This analysis is flawed, however, as it rests predominantly on the evidence of a single source: the Vita Mathildis by Donizone of Canossa. This document was produced more than half a century after the death of Boniface by an author who held complex political goals, but these have not been fully considered in the discussion of Boniface. Through the examination of the charter sources, this article argues that Donizone misrepresented Boniface’s actions and that there is considerable evidence that Boniface was not a consistent ally of the German emperors. Keywords: Italy; diplomatic; authority; power; relationship networks; Donizone of Canossa; Boniface of Canossa; Holy Roman Empire 1 Boniface of Canossa (c.985–1052) was one of the most influential figures in northern and central Italy in the early eleventh century, controlling extensive lands and rights in the counties of Mantua, Reggio, Modena, Parma, Bergamo, Brescia, Verona, Ferarra and Bologna, and in the duchy of Tuscany.1 Canossa itself dominated the important pass between Reggio and Tuscany. -

The Location the Rooms the Breakfast

The Location Located in a quiet green area outside the town (in Praticello , in the municipality of Gattatico) , the B&B "Il Portico" is located in a farmhouse comple- tely restored by keeping the rural original Emilian countryside style, without missing, the the same ti- me, all the comforts for a relaxing stay. The strate- gic location of the B&B allows in a few kilometers to reach Parma and Reggio Emilia , as well as the nearby natural areas of the “Po” and “Enza” rivers, and the Matildic or Parmesan hills. You are easily reach the nearby Parma and Reggio Emilia Exhibi- tions, also thanks to the nearby "Campegine - Terre di Canossa" A1 Motorway exit. The Interiors The residence, sur- rounded by vegeta- ble, orchard and a garden, has been re- The Rooms cently restructured: this operation made The 3 rooms, recently built, are each decorated and us protect the charac- furnished based on a particular theme, expressed by teristic elements of the name of the room. The areas vary from 20 squa- the rural houses ( re meters for "Ninfea" and "Glicine" romms, to the exposed brick , 23 s.m of the "Tulipano". All rooms, located on the wooden beams ) and first floor, in an exclusive and private area of the innovate all the tech- structure, have a large window overlooking the gar- The Breakfast nological systems, den, air conditioning / heating, and are furnished maximizing as much as possible the energy efficien- with a double bed, bedside tables, desk , sofa/bed In the breakfast room (of about 50 s.m.), in your cy of the building. -

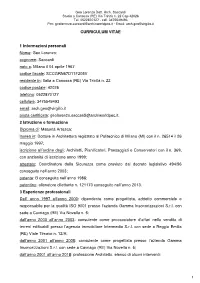

Curriculum Vitae

Geo Lorenzo Dott. Arch. Saccardi Studio a Canossa (RE) Via Trinità n. 22 Cap 42026 Tel. 0522870127 - cell. 3475549493 Pec: geolorenzo.saccardi©archinworldpec.it - Email: arch.geo©virgilio.it CURRICULUM VITAE 1 Informazioni personali Nome: Geo Lorenzo; cognome: Saccardi nato a: Milano il 04 aprile 1967 codice fiscale: SCCGRN67D11F205V residente in: Italia a Canossa (RE) Via Trinità n. 22 codice postale: 42026 telefono: 0522870127 cellulare: 3475549493 email: [email protected] posta certificata: [email protected]. 2 Istruzione e formazione Diploma di: Maturità Artistica; laurea in: Dottore in Architettura registrato al Politecnico di Milano (MI) con il n. 26514 il 26 maggio 1997; iscrizione all’ordine degli: Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori con il n. 369, con anzianità di iscrizione anno 1999; attestato: Coordinatore della Sicurezza come previsto dal decreto legislativo 494/96 conseguito nell’anno 2003; patente: B conseguita nell’anno 1986; patentino: allenatore dilettante n. 121173 conseguito nell’anno 2013. 3 Esperienze professionali Dall’ anno 1997 all’anno 2000: dipendente come progettista, addetto commerciale e responsabile per la qualità ISO 9001 presso l’azienda Gamma Insonorizzazioni S.r.l. con sede a Cavriago (RE) Via Novella n. 6; dall’anno 2000 all’anno 2003: consulente come procacciatore d’affari nella vendita di terreni edificabili presso l’agenzia immobiliare Intermedia S.r.l. con sede a Reggio Emilia (RE) Viale Timavo n. 12/A; dall’anno 2001 all’anno 2005: consulente come progettista presso l’azienda Gamma Insonorizzazioni S.r.l. con sede a Cavriago (RE) Via Novella n. 6; dall’anno 2001 all’anno 2018: professione Architetto, elenco di alcuni interventi: 1 Geo Lorenzo Dott. -

17 Marzo 2021

COVID-19, resoconto giornaliero 17-3-2021 In provincia di Reggio Emilia, su 215 nuovi casi positivi, 103 sono riconducibili a focolai, 112 classificati come sporadici. 208 casi sono in isolamento domiciliare, 7 pazienti ricoverati in terapia non intensiva. Nella giornata di ieri sono state vaccinate 1640 persone mentre per quella odierna ne erano programmate 1260. NUOVI CASI TOTALE TAMPONI POSITIVI 215 37615 TERAPIA INTENSIVA 31 ISOLAMENTO DOMICILIARE 208 6875 RICOVERO NON INTENSIVA 7 335 * GUARI TI CLINICAMENTE TOTALI 822 GUARITI CON TAMPONE NEGATIVO 29594 * Il dato comprende le persone positive in isolamento negli alberghi COVID Nuovi casi Albinea 1 Bagnolo in Piano 2 Baiso Bibbiano 1 Boretto 2 Brescello Cadelbosco Sopra 1 Campagnola Emilia 2 Campegine 2 Canossa 2 Carpineti 1 Casalgrande 7 Casina 2 Castellarano 10 Castelnovo Sotto 6 Castelnovo ne’ Monti 4 Cavriago 3 Correggio 10 Fabbrico 3 Gattatico 2 Gualtieri 6 Guastalla 6 Luzzara 3 Montecchio Emilia 1 Novellara 10 Poviglio 3 Quattro Castella 5 Reggio Emilia 63 Reggiolo 4 Rio Saliceto 4 Rolo 1 Rubiera 4 San Martino in Rio San Polo d’Enza 1 Sant’Ilario d’Enza 8 Scandiano 19 Toano Ventasso 1 Vetto 1 Vezzano sul Crostolo 1 Viano Villa Minozzo 3 Non residenti in provincia 2 Residenti in altra regione 8 Totale 215 Deceduti al 17 marzo 2021: Oggi comunichiamo 7 decessi - Donne: 1925 n.1 – 1929 n.1 – 1934 n.1 – 1943 n.1 - Uomini: 1935 n.1 – 1943 n.1 – 1962 n.1 Deceduti Comune di residenza Parziale Totale Albinea 12 Bagnolo in Piano 12 Baiso 8 Bibbiano 20 Boretto 11 Brescello 5 Cadelbosco -

Elenco Proftur Re 2011.Xls

Guide Turistiche N. COGNOME e NOME INDIRIZZO CAP CITTA' PROV. RECAPITO TELEFONICO LINGUA/E LOCALITA' ORD. 1 BAIOCCHI MARCELLO VIA EUROPA, 30 42044 BORETTO RE 0522/965203 340/2469940 FRANCESE BRESCELLO, [email protected] BORETTO, GUALTIERI E GUASTALLA 2 JAGER BEDOGNI VIA CALATAFIMI, 26 42100 REGGIO EMILIA RE 335/251717 0522/440942 TEDESCO REGGIO EMILIA E DONATELLA donatella.jagerbedogni@fast INGLESE PROVINCIA webnet.it 3 BENZI CRISTINA VIA MARCO 41012 CARPI MO 338/3415671 TEDESCO REGGIO EMILIA E MELONI, 1 [email protected] INGLESE PROVINCIA FRANCESE 4 BIANCHI MARIACHIARA VIA ASSEVERATI, 42100 REGGIO EMILIA RE 0522/351592 347/1717398 INGLESE REGGIO EMILIA, 12/1 [email protected] QUATTRO om CASTELLA, CARPINETI, CASINA, CANOSSA, S. POLO 5 BOGDANOVIC MEGLIOLI VIA CALATAFIMI, 26 42100 REGGIO EMILIA RE 333/8167570 0522/580767 FRANCESE REGGIO EMILIA E ANNE [email protected] INGLESE PROVINCIA 6 BOLLINA MARCO VIA S. DONATO, 11 40127 BOLOGNA BO 338/9048409 FRANCESE REGGIO EMILIA [email protected] 7 BORCIANI VIDA VIA A. CUGINI, 14/1 42100 REGGIO EMILIA RE 0522/1970926 349/0569107 INGLESE REGGIO EMILIA, [email protected] Boretto, Brescello, Campegine, Canossa, Carpineti, Casina, Correggio, Gattatico, Gualtieri, Guastalla, Luzzara, Montecchio, Novellara, Poviglio, Quattro Castella, Reggiolo, Rubiera, S. Martino in Rio, S. Polo, Scandiano Provincia di Reggio-Emilia Guide Turistiche 8 CANTARELLI SILVIA VIA DONIZETTI, 5 43022 MONTECHIARUGO PR 0521-659095 347/5423846 INGLESE REGGIO EMILIA E LO [email protected] PROVINCIA 9 CAPELLI CRISTIANA VIA C. CORSI, 26 43121 PARMA PR 0521/200084 FAX INGLESE REGGIO EMILIA, 0521/237794 338/6045686 BRESCELLO, [email protected] CANOSSA 10 CERVI GIULIANO VIA A. -

REGGIO EMILIA Guide Turistiche.Pdf

Guide Turistiche N. RECAPITO COGNOME e NOME INDIRIZZO CAP CITTA' PROV. LINGUA/E LOCALITA' Ord. TELEFONICO 0522/965203 340/2469940 BRESCELLO, BORETTO, 1 BAIOCCHI MARCELLO VIA EUROPA, 30 42044 BORETTO RE FRANCESE baiox@inwind. GUALTIERI E GUASTALLA it 335/251717 0522/440942 JAGER BEDOGNI TEDESCO REGGIO EMILIA E 2 VIA CALATAFIMI, 26 42100 REGGIO EMILIA RE donatella.jager DONATELLA INGLESE PROVINCIA bedogni@fast webnet.it 338/3415671 TEDESCO REGGIO EMILIA E 3 BENZI CRISTINA VIA MARCO MELONI, 1 41012 CARPI MO cribenzi@liber INGLESE PROVINCIA o.it FRANCESE 0522/351592 REGGIO EMILIA, 347/1717398 QUATTRO CASTELLA, 4 BIANCHI MARIACHIARA VIA ASSEVERATI, 12/1 42100 REGGIO EMILIA RE mariachiara.bi INGLESE CASINA, CANOSSA, S. [email protected] POLO om 333/8167570 BOGDANOVIC FRANCESE REGGIO EMILIA E 5 VIA CALATAFIMI, 26 42100 REGGIO EMILIA RE info@enoone. MEGLIOLI ANNE INGLESE PROVINCIA com 338/9048409 6 BOLLINA MARCO VIA S. DONATO, 11 40127 BOLOGNA BO m.bollina@alic FRANCESE REGGIO EMILIA e.it Provincia di Reggio Emilia Guide Turistiche N. RECAPITO COGNOME e NOME INDIRIZZO CAP CITTA' PROV. LINGUA/E LOCALITA' Ord. TELEFONICO 0522/430760 349/0569107 NOVELLARA, GUASTALLA, 7 BORCIANI VIDA VIA CUGINI, 14/1 42100 REGGIO EMILIA RE INGLESE borciani@alice REGGIO EMILIA .it 0521-659095 MONTECHIARUGO 347/5423846 REGGIO EMILIA E 8 CANTARELLI SILVIA VIA DONIZETTI, 5 43022 PR INGLESE LO silviacantarelli PROVINCIA @tiscali.it 338/6045686 REGGIO EMILIA, 9 CAPELLI CRISTIANA VIA C. CORSI, 26 43121 PARMA PR cristiana.capell INGLESE BRESCELLO, CANOSSA [email protected] 0522/521563 REGGIO EMILIA - COLLINA 10 CERVI GIULIANO VIA A. FRANK, 11/A 42100 LOC. -

COVID-19, Resoconto Giornaliero 23-10-2020 in Provincia Di Reggio

COVID-19, resoconto giornaliero 23-10-2020 In provincia di Reggio Emilia, su 130 nuovi casi positivi, 4 sono riconducibili a focolai già noti, 126 classificati come sporadici ( i casi sporadici sono quelli per cui l’attività di tracciamento non riconduce ad un focolaio, per cui restano casi singoli, non associabili ad altri. Nel proseguo delle indagini se vengono individuati collegamenti con altri casi entrano a far parte di un focolaio ). Tutti i casi sono in isolamento domiciliare. NUOVI CASI TOTALE TAMPONI POSITIVI 130 6899 TERAPIA INTENSIVA 3 ISOLAMENTO DOMICILIARE 130 1538 RICOVERO NON INTENSIVA 111 * GUARITI CLINICAMENTE TOTALI 361 GUARITI CON DOPPIO TAMPONE NEGATIVO 4937 * Il dato comprende le persone positive in isolamento negli alberghi COVID Nuovi casi Albinea 3 Bagnolo in Piano Baiso 4 Bibbiano 4 Boretto Brescello Cadelbosco Sopra 1 Campagnola Emilia 1 Campegine 2 Canossa 1 Carpineti 1 Casalgrande 2 Casina Castellarano 1 Castelnovo Sotto 1 Castelnovo ne’ Monti 1 Cavriago 2 Correggio 3 Fabbrico Gattatico 4 Gualtieri Guastalla 6 Luzzara Montecchio Emilia Novellara 2 Poviglio 2 Quattro Castella 3 Reggio Emilia 60 Reggiolo Rio Saliceto Rolo Rubiera 2 San Martino in Rio 1 San Polo d’Enza 1 Sant’Ilario d’Enza 4 Scandiano 8 Toano Ventasso Vetto Vezzano sul Crostolo Viano 7 Villa Minozzo Non residenti in provincia 3 Residenti in altra regione Totale 130 Deceduti al 23 ottobre 2020: -Uomini: -Donne: Deceduti Comune di residenza Parziale Totale Albinea 7 Bagnolo in Piano 7 Baiso 2 Bibbiano 11 Boretto 5 Brescello 2 Cadelbosco Sopra 10