Aida,Save Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad Peruana De Ciencias Aplicadas Facultad

Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K- Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 10/10/2021 11:56:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/648589 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIONES PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y MEDIOS INTERACTIVOS Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K-Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS. TESIS Para optar el título profesional de Licenciado en Comunicación Audiovisual y Medios Interactivos AUTOR(A) Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie (0000-0003-4569-9612) ASESOR(A) Calderón Chuquitaype, Gabriel Raúl (0000-0002-1596-8423) Lima, 01 de Junio de 2019 DEDICATORIA A mis padres Abraham y Luz quienes con su amor, paciencia y esfuerzo me han permitido llegar a cumplir hoy un sueño más. -

Korean Language Hymns.Pdf

TITLE TUNE 001 Praise God from whom all blessings flow OLD HUNDREDTH: 8.8.8.8. 002 To Father, Son, and Holy Ghost ORTONVILLE: 8.6.8.6.6. 003 Glory be to the Father MEINEKE: IRREG. 004 Glory be to the Father GREATOREX: IRREG. 005 Let earth and sky SESSIONS: 8.8.8.8. 006 Now to the King of heav'n ST. JOHN: 6.6.6.6.8.8. 007 Glory to the Father BETHEL PARK: IRREG. 008 Holy, holy, holy, Lord God Almighty! NICAEA: 12.13.12.10 009 Heaven is full of Your glory IRREG. 010 Come, Thou Almighty King ITALIAN HYMN: 6.6.4.6.6.6.4. 011 Let people all worship our God IRREG. 012 Jehovah, let me now adore Thee DIR, DIR, JEHOVAH: 9.10.9.10.10.10. 013 Eternal Kingdom of God IRREG. 014 The God of Abraham praise YIGDAL (LEONI): 6.6.8.4.D. 015 Love divine, all loves excelling BEECHER: 8.7.8.7.D. 016 God of love and mercy great 7.6.7.6.7.5.7.5. 017 God of love and mercy great IRREG. 018 Let us join to sing together IRREG. 019 Hark, ten thousand harps and voices HARWELL: 8.7.8.7.8.8.ALLELUIAS 020 Begin, my tongue, some heavenly theme MANOAH: 8.6.8.6. 021 Praise to the Lord, the Almighty LOBE DEN HERREN: 14.14.4.7.8. 022 Rejoice, the Lord is King DARWALL: 6.6.6.6.REF. 023 Of a thousand tongues to sing AZMON: 8.6.8.6. -

We Gather We Prepare

May 22, 2011 Our Community Gathers Rev. Kristen Klein-Cechettini Mark Eggleston We Gather Prelude HeavenSound Handbells From many places we gather here. This Grandioso is a high point of our by Darrell Day week. We see our friends. We make + new friends. And we Call to Worship Rev. Janice Ladd spend time with The Congregational Response: “Abide in us, O God!” Friend -- the loving Christ who meets us + Hymn where we are, as we are. In this Sanctuary Lead Me, Lord we worship, and by Wayne and Elizabeth Goodine through worship the courage within us is kindled to inspire courageous living beyond this place. We Prepare As the prelude begins, the congregation is invited to be in an attitude of expectation for the worship of God. + Please rise in body or spirit. Reading from the Hebrew Scriptures Bill O'Rourke (9 am) Marcial Renteria (11 am) Psalm 31:1-5, 15-16 In you, O LORD, I seek refuge; do not let me ever be put to shame; in your righteousness deliver me. Incline your ear to me; rescue me speedily. Be a rock of refuge for me, a strong fortress to save me. You are indeed my rock and my fortress; for your name's sake lead me and guide me, take me out of the net that is hidden for me, for you are my refuge. Into your hand I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, O LORD, faithful God. My times are in your hand; deliver me from the hand of my enemies and persecutors. -

Martha's Vineyard Concert Series

THA’S VINEY AR ARD M SUMMER 2017 CONCERT SERIES 2ND ANNUAL SEASON ALL SHOWS ON SALE NOW! MVCONCERTSERIES.COM MARTHA’S VINEYARD CONCERT SERIES your year - round connection to Martha’s Vineyard SUmmER LINE-UP! JUNE 28 • AIMEE MANN over 6,500 photo, canvas WITH SPECIAL GUEST JONATHAN COULTON images & metal prints published agendas JULY 6 • LOUDON WAINWRIGHT III daily photos calendars JULY 13 • PINK MARTINI sent to your inbox notecards WITH LEAD SINGER CHINA FORBES JULY 18 • GRAHAM NASH JULY 23 • PRESERVATION HALL JAZZ BAND JULY 29 • JACKOPIERCE WITH SPECIAL GUEST IAN MURRAY FROM VINEYARD VINES AUGUST 15 • THE CAPITOL STEPS ALL NEW SHOW! ORANGE IS THE NEW BARACK AUGUST 19 • ARETHA FRANKLIN AUGUST 21 • DIRTY DOZEN BRAss BAND AUGUST 23 • BLACK VIOLIN GET YOUR TICKETS TODAY! www.vineyardcolors.com MVCONCERTSERIES.COM AIMEE MANN WITH SPECIAL GUEST JONATHON COULTON WEDNESDAY, JUNE 28 | MARTHA’S VINEYARD PAC Aimee Mann is an American rock singer-songwriter, bassist and guitarist. In 1983, she co-founded ‘Til Tuesday, a new-wave band that found success with its first album, Voices Carry. The title track became an MTV favorite, winning the MTV Video Music Award for Best New Artist, propelling Mann and the band into the spotlight. After releasing three albums with the group, she broke up the band and embarked on a solo career. Her first solo album, Whatever, was a more introspective, folk-tinged effort than ‘Til Tuesday’s albums, and received uniformly positive reviews upon its release in the summer of 1993. Mann’s song “Save Me” from the soundtrack to the Paul Thomas Anderson film Magnolia was nominated for an Academy® Award and a Grammy®. -

BTS' A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker a Dissertation

BTS’ A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Anis Bawarshi, Chair Nancy Bou Ayash Juan C. Guerra Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2019 Judy-Gail Baker University of Washington Abstract BTS’ A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Anis Bawarshi English As a transcultural K-Pop fandom, 아미 [A.R.M.Y.] perform out-of-school, Web 2.0 English[es] composing to cooperatively translate, exchange and broker content for parasocially relating to/with members of the supergroup 방탄소년단 [BTS] and to/with each other. Using critical linguistic ethnography, this study traces how 아미 microbloggers’ digital conversations embody Jenkins’ principles of participatory fandom and Wenger’s characteristics of communities of learning practice. By creating Wei’s multilingual translanguaging spaces, 아미 assemble interest-based collectives Pérez González calls translation adhocracies, who collaboratively access resources, produce content and distribute fan compositions within and beyond fandom members. In-school K-12 and secondary learning writing Composition and Literacy Studies’ theory, research and pedagogy imagine learners as underdeveloped novices undergoing socialization to existing “native” discourses and genres and acquiring through “expert” instruction competencies for formal academic and professional “lived” composing. Critical discourse analysis of 아미 texts documents diverse learners’ initiating, mediating, translating and remixing transmodal, plurilingual compositions with agency, scope and sophistication that challenge the fields’ structural assumptions and deficit framing of students. -

Finding Grace in the Concert Hall: Community and Meaning Among Springsteen Fans

FINDING GRACE IN THE CONCERT HALL: COMMUNITY AND MEANING AMONG SPRINGSTEEN FANS By LINDA RANDALL A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY On Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Religion December 2008 Winston Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Lynn Neal, PhD. Advisor _____________________________ Examining Committee: Jeanne Simonelli, Ph.D. Chair _____________________________ LeRhonda S. Manigault, Ph.D _____________________________ ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, my thanks go out to Drs. Neal and Simonelli for encouraging me to follow my passion and my heart. Dr. Neal helped me realize a framework within which I could explore my interests, and Dr. Simonelli kept my spirits alive so I could nurse the project along. My concert-going partner in crime, cruisin’tobruce, also deserves my gratitude, sharing expenses and experiences with me all over the eastern seaboard as well as some mid-America excursions. She tolerated me well, right up until the last time I forgot the tickets. I also must recognize the persistent assistance I received from my pal and companion Zero, my Maine Coon cat, who spent hours hanging over my keyboard as I typed. I attribute all typos and errors to his help, and thank him for the opportunity to lay the blame at his paws. And lastly, my thanks and gratitude goes out to Mr. Bruce Frederick Springsteen, a man of heart and of conscience who constantly keeps me honest and aware that “it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive (Badlands).” -

Save Me HV PK

SAVE ME Directed by Robert Cary Story by Craig Chester and Alan Hines Screenplay by Robert Desiderio Starring Chad Allen, Robert Gant, Judith Light 96 minutes, color, 2007 First Run Features 630 Ninth Avenue, Suite 1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600/Fax (212) 989-7649 www.firstrunfeatures.com 1 of 18 SYNOPSIS 1 Save Me is a love story about Mark, a sex and drug addicted young man who after an accidental overdose finds he’s been checked into a Christian retreat for ‘Ex-Gays’. Gayle, the director of the ministry run together with her husband Ted, believes she can help cure young men of their ‘gay affliction’ through spiritual guidance. At first, Mark resists, but soon takes the message to heart. As Mark’s fellowship with his fellow Ex-Gays grow stronger, however, he finds himself powerfully drawn to Scott, another young man battling family demons of his own. As their friendship begins to develop into romance, Mark and Scott are forced to confront the new attitudes they’ve begun to accept, and Gayle finds the values she holds as an absolute truth to be threatened. A complex and deeply sympathetic look into both sides of one of the most polarizing religious and sexual debates in America. SYNOPSIS 2 Though there is no sound scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed, the ex-gay movement has been at the polarizing center of religious and sexual debates in the U.S. since the 1970s. In Save Me , an exceptionally layered, intelligent and sensitive drama brought to life by director Robert Cary, Mark (Chad Allen) a self-destructive addict hooked to anonymous sex and narcotics finally hits bottom. -

My Mental Health Matters Selected Art and Poetry Submissions from the International Youth Day Campaign 2014

Economic & Social MY MENTAL HEALTH MATTERS Affairs SELECTED ART AND POETRY SUBMISSIONS FROM THE INTERNATIONAL YOUTH DAY CAMPAIGN 2014 United Nations Division for Social Policy and Development Department of Economic and Social Affairs MY MENTAL HEALTH MATTERS SELECTED ART AND POETRY SUBMISSIONS FROM THE INTERNATIONAL YOUTH DAY CAMPAIGN 2014 United Nations New York, 2014 DESA The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which Member States of the United Nations draw to review common problems and take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Disclaimer: The artwork, photos and poems contained in this booklet do not reflect the views or opinions of the United Nations. All entries are hereby reproduced with the written permission of the artists. FOREWORD International Youth Day is commemorated annually on 12 August. Each year, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) selects a theme for the day with input from youth organizations and members of the UN Inter-Agency Network in Youth development. -

Media/Entertainment Rise of Webtoons Presents Opportunities in Content Providers

Media/Entertainment Rise of webtoons presents opportunities in content providers The rise of webtoons Overweight (Maintain) Webtoons are emerging as a profitable new content format, just as video and music streaming services have in the past. In 2015, webtoons were successfull y monetized in Korea and Japan by NAVER (035420 KS/Buy/TP: W241,000/CP: W166,500) and Kakao Industry Report (035720 KS/Buy/TP: W243,000/CP: W158,000). In late 2018, webtoon user number s April 9, 2020 began to grow in the US and Southeast Asia, following global monetization. This year, NAVER Webtoon’s entry into Europe, combined with growing content consumption due to COVID-19 and the success of several webtoon-based dramas, has led to increasing opportunities for Korean webtoon companies. Based on Google Trends Mirae Asset Daewoo Co., Ltd. data, interest in webtoons is hitting all-time highs across major regions. [Media ] Korea is the global leader in webtoons; Market outlook appears bullish Jeong -yeob Park Korea is the birthplace of webtoons. Over the past two decades, Korea’s webtoon +822 -3774 -1652 industry has created sophisticated platforms and content, making it well-positioned for [email protected] growth in both price and volume. 1) Notably, the domestic webtoon industry adopted a partial monetization model, which is better suited to webtoons than monthly subscriptions and ads and has more upside potent ial in transaction volume. 2) The industry also has a well-established content ecosystem that centers on platforms. We believe average revenue per paying user (ARPPU), which is currently around W3,000, can rise to over W10,000 (similar to that of music and video streaming services) upon full monetization. -

Onomatope Dan Mimesis Bahasa Korea Dalam Cerita

ONOMATOPE DAN MIMESIS BAHASA KOREA DALAM CERITA HWAYANGYȎNHWA: SAVE ME KARYA LICO/BIG HIT ENTERTAIMENT ARINA PRAMUDITA NIM 16345020050092 PROGRAM STUDI BAHASA KOREA AKADEMI BAHASA ASING NASIONAL JAKARTA 2020 ONOMATOPE DAN MIMESIS BAHASA KOREA DALAM CERITA HWAYANGYȎNHWA: SAVE ME KARYA LICO/BIG HIT ENTERTAIMENT Karya Tulis Akhir Ini Diajukan Untuk Melengkapi Pernyataan Kelulusan Program Diploma Tiga Akademi Bahasa Asing Nasional ARINA PRAMUDITA NIM 16345020050092 PROGRAM STUDI BAHASA KOREA AKADEMI BAHASA ASING NASIONAL JAKARTA 2020 ABSTRAK Nama : Arina Pramudita Fakultas/Jurusan : Bahasa Korea Judul KTA : Onomatope dan Mimesis Bahasa Korea Dalam Webtoon Hwayangyȏnhwa: Save Me Karya Lico/Big Hit Entertainment Onomatope adalah pengimitasian dari suara alami yang didengar dan dibentuk menjadi sebuah kata, sedangkan mimesis adalah sesuatu yang bukan berupa suara, atau tidak berhubungan dengan indra pendengaran, namun diubah lalu diekspresikan dengan merujuk kepada indra pendengaran. Dalam komik, onomatope dan mimesis selalu dimanfaatkan sebagai elemen pendukung dan unsur estetik. Penulisan Karya Tulis Akhir ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan perbedaan onomatope dan mimesis, karakterististik onomatope dan mimesis dari kedua bahasa, dan perbandingan varian bentuk dan makna onomatope dan mimesis yang terdapat dalam webtoon Hwayangyȏnhwa: Save Me karya Lico/Big Hit Entertainment. Karya tulis ini adalah hasil dari penelitian menggunakan metode deskriptif kualitatif berdasarkan studi kepustakaan. Hasil penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa menghafal -

BTS Author, Composer, and Producer Stats

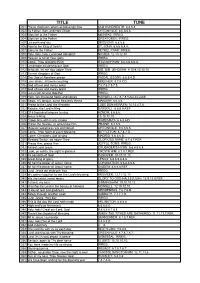

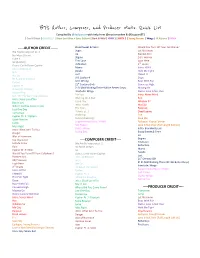

BTS Author, Composer, and Producer stats: Quick List Compiled By @dailyunnie with help from @musicmunkee & @SupportBTS 2 Cool 4 Skool | O!RUL8,2? | Skool Luv Affair + Spec. Edition | Dark & Wild | HYYH 1 | HYYH 2 | Young Forever | Wings | JP Albums | YNWA -----AUTHOR CREDIT------ Blood Sweat & Tears Would You Turn Off Your Cellphone? We Are Bulletproof pt. 2 Begin Let Me Know Lie Blanket Kick No More Dream Stigma 24/7 Heaven I Like It First Love Look Here Gil (hidden) Reflection 2nd Grade Outro: Circle Room Cypher Intro: O!RUL8,2? Mama Intro: HYYH Awake Hold Me Tight N.O We On Lost I Need U BTS Cypher 4 Dope If I Ruled The World Coffee Am I Wrong Boyz With Fun 21st Century Girls Converse High Cypher Pt. 1 Attack On Bangtan 2! 3! (Still Wishing There Will be Better Days) Moving On Interlude: Wings Outro: Love Is Not Over Satoori Rap Skit: On The Start Line (hidden) For You Intro: Never Mind Wishing On A Star Run Intro: Skool Luv Affair Boy In Luv Good Day Whalien 52 Intro: Youth Ma City Where Did You Come From? The Stars Baepsae Just One Day I Like It pt. 2 Dead Leaves Tomorrow Wake Up Fire Cypher Pt. 2: Triptych Spine Breaker Outro (Wake Up) Save Me Supplemental Story: YNWA Epilogue: Young Forever Jump Miss Right Not Today Love Is Not Over (Full Length Edition) Outro: Wings Intro: Boy Meets Evil Intro: What Am I To You Danger Spring Day Blood Sweat & Tears Lie War of Hormone Hip Hop Lover ----COMPOSER CREDIT---- Stigma First Love Let Me Know We Are Bulletproof pt. -

An Analysis of Metaphor Used in Harris Jung's Selected

AN ANALYSIS OF METAPHOR USED IN HARRIS JUNG’S SELECTED SONGS A GRADUATING PAPER Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of a Requirements for Gaining The Bachelor Degree in English Literature By: Luthfi Bahrul Anwari 15150046 ENGLISH DEPARTEMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND CULTURAL SCIENCES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF SUNAN KALIJAGA YOGYAKARTA 2019 SELECTED SONGS ii iii iv AN ANALYSIS OF METAPHOR USED IN HARRIS JUNG’S SELECTED SONGS By: Luthfi Bahrul Anwari ABSTRACT This research is focused on the study of meaning and types of metaphors contained in the Harris Jungs song. Almost all Harris Jung songs are religious- themed and full with messages of kindness. The researcher chooses 10 songs to be analysed in this research. Those songs are, Salam Alaikum, Good Life, Rasool Allah, I Promise, Love who You are, Let Me Breathe, Paradise, You’re My Life, Save Me from Myself and The One. The researcher chooses the songs because they are the most watched Harris Jung’s song in YouTube. The researcher in this research uses semantic theory that focuses on metaphors, according to the purpose of this research which is to examine the meaning and types of metaphors. The theory is proposed by Ullmann then is adapted by Sumarsono. This research uses qualitative methods, while the data collection method uses documentation techniques. As a result, the researcher finds 12 metaphors in the lyrics of the selected songs which included, 1 anthropomorphic metaphor, 11 concrete to abstract metaphors. The domination of concrete to abstract metaphor shows that the songwriters wants to depict the existence of God through existing symbols, and shows God's love for humans.