Wealth and Hierarchy in the Intermediate Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Prehistoric Civilizations of Nuclear America GORDON R

The Prehistoric Civilizations of Nuclear America GORDON R. WILLEY H mwd University INTRODUCTION HE native agricultural civilizations of the New World had their begin- Tnings and their highest development in those areas that have been sub- sumed under the term “Nuclear America” (Kroeber 1948: 779). The desig- nation has both a geographical and a cultural connotation. The areas involved embrace central and southern Mexico, Central America, the north Andes, and Peru. This is the axis of aboriginal high culture in the Americas and, as such, the major center of prehistoric diffusion for the western hemisphere. To the best of our knowledge, it stands clearly apart and essentially independent from the comparable culture core of the Old World. Kroeber (1948: 784-85; 1952:377-95) has suggested the analogy between the American civilizational nucleus of Mexico-Peru and the “Oikoumene” of the Old World. Readapting the old Greek concept of the “inhabited” or civil- ized world (Kroeber 1952:379 and 392), he has defined the Oikoumene for purposes of culture-historical analysis as (‘ . the millennially interrelated higher civilizations in the connected mainland masses of the Eastern hemi- sphere,” and “as ’a great web of culture growth, areally extensive and rich in content.” It is, in effect, a vast diffusion sphere (see Hawkes 1954) interlinked across continents by common cultural content. The comparison with Nuclear America seems particularly apt. In both cases the great historic nexuses have considerable time depth at their centers, and in both they have influenced those cultures marginal to them at relatively later points on the time scale. -

Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia

This is an extract from: Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia Jeffrey Quilter and John W. Hoopes, Editors published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2003 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html The Political Economy of Pre-Colombian Goldwork: Four Examples from Northern South America Carl Henrik Langebaek Universidad de los Andes Introduction: The Problem ome twenty years ago, Alicia Dussán de Reichel (1979: 41) complained that studies that “set out to place the prehistoric metallurgy of Colombia within a wider context Sof cultural development” were not very numerous. Despite a great deal of research on Pre-Columbian goldwork since, the same observation remains true today. One source of frustration comes from the fact that most archaeologists focus on the study of metallurgy as a goal in itself. Although researchers have produced detailed descriptions about the techno- logical characteristics of Pre-Columbian goldwork (Scott 1981), timelines, definitions of “styles” and “traditions,” as well as correlations among styles across Colombia, Lower Central America, and Ecuador (Bray 1981; 1992a; 1997; Plazas and Falchetti 1983), and identifica- tions of plant and animal species represented in ornaments (Legast 1987), they have rarely placed goldwork within a social context (Looper 1996) or incorporated it in models related to social change. Whatever improvement in the research on Pre-Columbian metal objects there has been, further progress will be limited if it is not aimed at understanding the way societies function and change (Lechtman 1984). -

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by O Number 414 Thu Axmucanmuum"Ne Okcitynatural HITORY March 24, 1930

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by o Number 414 THu AxmucANMuum"Ne okCityNATURAL HITORY March 24, 1930 59.82 (728.1) STUDIES FROM THE DWIGHT COLLECTION OF GUATEMALA BIRDS. II BY LUDLOW GRISCOM This is the second' preliminary paper, containing descriptions of new forms in the Dwight Collection, or revisions of Central American birds, based almost entirely on material in The American Museum of Natural History. As usual, all measuremenits are in millimeters, and technical color-terms follow Ridgway's nomenclature. The writer would appreciate prompt criticism from his colleagues, for inclusion in the final report. Cerchneis sparveria,tropicalis, new subspecies SUBSPECIFIC CHARACTERS.-Similar to typical Cerchneis sparveria (Linnleus) of "Carolina," but much smaller and strikingly darker colored above in all ages and both sexes; adult male apparently without rufous crown-patch and only a faint tinge of fawn color on the chest; striping of female below a darker, more blackish brown; wing of males, 162-171, of females, 173-182; in size nearest peninularis Mearns of southern Lower California, which, however, is even paler than phalena of the southwestern United States. TYPE.-No. 57811, Dwight Collection; breeding male; Antigua, Guatemala; May 20, 1924; A. W. Anthony. MATERIAL EXAMINED Cerchneis sparveria spar'eria.-Several hundred specimens from most of North America, e.tern Mexico and Central America, including type of C. s. guatemalenis Swann from Capetillo, Guatemala. Cerchneis sparveria phalkna.-Over one hundred specimens from the south- western United States and western Mexico south to Durango. Cerchneis sparveria tropicalis.-Guatemala: Antigua, 2 e ad., 1 6" imm., 2 9 ad., 1 9 fledgeling. -

1 Abbreviated Curriculum Vitae Rosemary A. Joyce Education

Abbreviated curriculum vitae Rosemary A. Joyce Education: AB May 1978 Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Honors paper: Fejervary-Meyer 1: Dimensions of Time and Space. PhD May 1985 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Dissertation: Cerro Palenque, Valle del Ulua, Honduras: Terminal Classic Interaction on the Southern Mesoamerican Periphery. Employment history: University of California, Berkeley: Professor, Anthropology (July 2001-present); Associate Professor (July 1994- June 2001) Interim Dean of the Graduate Division (July 2014-December 2014); Associate Dean of the Graduate Division (July, 2011-June 2014, January-June 2015) Chair, Department of Anthropology (January 2006- December 2009) Director, Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology (July 1994-June 1999) Harvard University: Associate Professor (June 1991-June 1994), Assistant Professor (July 1989-June 1991), Lecturer (July 1986-July 1989), Department of Anthropology Assistant Curator of Precolumbian Archaeology, Peabody Museum (September 1985-June 1994) Assistant Director, Peabody Museum (July 1986-July 1989) University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign: Lecturer in Anthropology (August 1984-May 1985) Jackson (Michigan) Community College: Instructor, Social Sciences department (August 1983-January 1984) Fellowships, honors and awards: University of Colorado, Boulder Distinguished Archaeology Lecturer, February 2016 Smithsonian Fellow, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, August-December 2015. John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, 2010-2011. Astor Visiting Lecturership, Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford University, Fall 2010. Fulbright Senior Scholar, Universidad de Costa Rica, June 2007 Leon Henkin Citation for Distinguished Service, Committee on Student Diversity and Academic Development, Berkeley Division of the Academic Senate of the University of California (with Margaret W. Conkey, Kent Lightfoot, and Laurie Wilkie), 2007. -

The Grammar of Teribe Verb Serialization in a Cross-Chibchan Perspective1

THE GRAMMAR OF TERIBE VERB SERIALIZATION IN A CROSS-CHIBCHAN PERSPECTIVE1 J. Diego Quesada This paper describes the grammar of serial verb constructions in Teribe, a Chibchan language of Costa Rica and Panama; it also analyzes the grammaticalization of minor components of Teribe serial verb construc- tions as potential auxiliaries. By comparing the Teribe verb serialization patterns with the behavior of positionals in three neighboring Chibchan languages, Bribri and Cabecar (Costa Rica) and Cuna (Panama and Colombia), the paper explores the grammaticalization path of verb seri- alization in Chibchan. The analysis suggests that the difference between Bribri, Cabecar, Teribe, and Cuna in terms of positionals has to do with varying degrees of grammaticalization of those verbs. 1 Introduction The Chibchan languages extend from Northeastern Honduras, through the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua, most of Costa Rica and Panama, Colombia and West of Venezuela; they represent the most widespread language family in the cultural and linguistic area known as the Inter- mediate Area.2 The Intermediate Area borders with Mesoamerica to the North and with the Peruvian (Andean) and Amazonian areas to the South. On the basis of important differences that recent archeolog- ical, anthropological and linguistic research have established between Central America and Colombia, the Chibchan world has been divided into these two geographic zones (cf. Quesada 2007); one of these differences has to do with the category of auxiliaries, which seems 1 I wish to express my sincere thanks to Adelfia Gonzalez and Ali Segura, native speakers of Teribe and Bribri, respectively. Thanks are also due to the editors of the volume for insightful criticism and suggestions on an earlier version of this paper. -

Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia

This is an extract from: Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia Jeffrey Quilter and John W. Hoopes, Editors published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2003 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html GOLD AND POWER IN ANCIENT COSTA RICA, PANAMA, AND COLOMBIA GOLD AND POWER IN ANCIENT COSTA RICA, PANAMA, AND COLOMBIA A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks 9 and 10 October 1999 Jeffrey Quilter and John W. Hoopes, Editors Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2003 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Frontispiece: King Antonio Saldaña of Talamanca wearing a necklace of tumbaga bird-effigy pendants. Detail of a portrait by S. Llorente, 1892. ©1992 National Museum of Costa Rica, Editorial Escudo de Oro, S.A. (Calvo Mora, Bonilla Vargas, and Sánchez Pérez, 1992) Cataloging-in-Publication Data for this volume is on file with the Library of Congress. ISBN 0-88402-294-3 Contents Map: Archaeological culture areas and contemporary states in southern Central America and Colombia vii Chronological Chart: Prehistoric Costa Rica and Panama viii Chronological Chart: Prehistoric Colombia ix Introduction: The Golden Bridge of the Daríen 1 Jeffrey Quilter “Catching the Light”: Technologies of Power and Enchantment in Pre-Columbian Goldworking 15 Nicholas J. Saunders Goldwork and Chibchan Identity: Endogenous Change and Diffuse Unity in the Isthmo-Colombian Area 49 John W. Hoopes and Oscar M. Fonseca Z. -

A Case Study from the Peruvian Andes

plants Article Medicinal Plants for Rich People vs. Medicinal Plants for Poor People: A Case Study from the Peruvian Andes Fernando Corroto 1,2, Jesús Rascón 1 , Elgar Barboza 1,3 and Manuel J. Macía 2,4,* 1 Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo Sustentable de Ceja de Selva, Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas, Calle Universitaria N◦ 304, Chachapoyas, Amazonas 01001, Peru; [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (J.R.); [email protected] (E.B.) 2 Departamento de Biología, Área de Botánica, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Calle Darwin 2, ES-28049 Madrid, Spain 3 Dirección de Desarrollo Tecnológico Agrario, Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria, Avenida La Molina N◦ 1981, Lima 15024, Peru 4 Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Cambio Global (CIBC-UAM), Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Calle Darwin 2, ES-28049 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-91-497-81-07 Abstract: Traditional knowledge (TK) of medicinal plants in cities has been poorly studied across different inhabitants’ socioeconomic sectors. We studied the small city of Chachapoyas (~34,000 in- habitants) in the northern Peruvian Andes. We divided the city into three areas according to the socio-economic characteristics of its inhabitants: city center (high), intermediate area (medium), and city periphery (low). We gathered information with 450 participants through semi-structured inter- views. Participants of the city periphery showed a higher TK of medicinal plants than participants of Citation: Corroto, F.; Rascón, J.; the intermediate area, and the latter showed a higher TK than participants of the city center. -

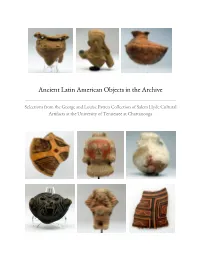

Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive

Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive Selections from the George and Louise Patten Collection of Salem Hyde Cultural Artifacts at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive: Selections from the George and Louise Patten Collection of Salem Hyde Cultural Artifacts at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga An exhibition catalog authored by students enrolled in Professor Caroline “Olivia” M. Wolf’s Latin American Visual Culture from Ancient to Modern class in Spring 2020. ● Heather Allen ● Abby Kandrach ● Rebekah Assid ● Casper Kittle ● Caitlin Ballone ● Jodi Koski ● Shaurie Bidot ● Anna Lee ● Katlynn Campbell ● Peter Li ● McKenzie Cleveland ● Sammy Mai ● Keturah Cole ● Amber McClane ● Kyle Cumberton ● Silvey McGregor ● Morgan Craig ● Brcien Partin ● Mallory Crook ● Kaitlyn Seahorn ● Nora Fernandez ● Cecily Salyer ● Briana Fitch ● Stephanie Swart ● Aaliyah Garnett ● Cameron Williams ● Hailey Gentry ● Lauren Williamson ● Riley Grisham ● Hannah Wimberly Lowe ● Chelsey Hall © 2020 by the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgements 5 A Collaborative Approach to Undergraduate Research 6 A Note on the Collection 7 Animal Figures 8 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Figure 10 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Monkey Figurine 11 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Sherd 12 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Bird-Shaped Whistle 13 Anthropomorphic Ceramics 14 Pre-Columbian Vessel Sherd 15 Pre-Columbian Handle Sherd 17 Pre-Columbian Panamanian Ceramic Vessel with Decorated -

Interregional “Landscapes of Movement” and the La Unión Archaeological District of Northeastern Costa Rica

INTERREGIONAL “LANDSCAPES OF MOVEMENT” AND THE LA UNIÓN ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISTRICT OF NORTHEASTERN COSTA RICA By Copyright 2012 Adam Kevin Benfer Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. ______________________________ Dr. John W. Hoopes, Chairperson ______________________________ Dr. Peter H. Herlihy ______________________________ Dr. Frederic Sellet Date Defended: 4/12/2012 The Thesis Committee for Adam Kevin Benfer certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: INTERREGIONAL “LANDSCAPES OF MOVEMENT” AND THE LA UNIÓN ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISTRICT OF NORTHEASTERN COSTA RICA ______________________________ Dr. John W. Hoopes, Chairperson Date approved: 4/18/2012 ii ABSTRACT In Costa Rica and the Circum-Caribbean, identifying the locations, functions, and evolution of past networks of human movement contributes to understanding pre-Hispanic interregional interactions and exchanges. I hypothesize the existence of Period VI (A.D. 1000 – 1550) routes of interdistrict movement between the northeastern Caribbean Lowlands and the Central Highlands of Costa Rica. To test this hypothesis, I use a multiple-method approach: archival research of historic roads and paths, archaeological reconnaissance of late pre-Hispanic features, and geographic information systems (GIS) least cost path (LCP) and least cost corridor (LCC) analyses. I discuss the possible functions and evaluate the roles of these routes among other interconnected networks. While archaeologists have documented some pre-Hispanic roads and paths in Costa Rica, few pre-Hispanic interregional routes of human movement have been identified. During the Colonial Period, the Spanish utilized these same landscapes of movement and waterscapes of movement for their own transportation and communication. -

Questions for Staff

DOCKET 08-AFC-13 DATE AUG 17 2010 RECD. AUG 17 2010 This Page Intentionally Left Blank Applicant’s Summary of Cultural Resource Impacts and Response to the CEC Staff’s Supplemental Staff Assessment Part II August 17, 2010 This Page Intentionally Left Blank APPLICANT’S SUMMARY OF CULTURAL RESOURCE IMPACTS AND RESPONSE TO THE CEC STAFF’S SUPPLEMENTAL STAFF ASSESSMENT PART II August 17, 2010 Testimony of: Rachael Nixon and Jeremy Hollins The following is the applicant’s review and comments on the cultural resource analysis contained in the Supplemental Staff Assessment Part II. Prehistoric Archaeological Resources Following its analysis of the Calico project site, the applicant and their consultants have concluded that, the project will have no effect on resources determined to be eligible. The CEC Staff did not concur with the conclusions of the applicant and concludes that it does not appear that prehistoric archaeological resource data potential has been adequately assessed or exhausted through recordation. Staff recommends that further sampling of the prehistoric archaeological sites within the project area be requ ired in order to mitigate theses resources. ‐ Staff proposes CUL‐4 and CUL‐5 requiring a post‐certification refinement study to complete the applicant’s effort to mitigate CRHR – and – NRHP eligible prehistoric sites that could be impacted by the project. The study would provide the applicant with information upon which to base project design changes to avoid impacts to prehistoric archaeological sites, and to verify the potential presence of such deposits and thereby provide more refined mitigation measures, particularly a more refined archaeological monitoring protocol. -

The Quintessential Naturalist: Honoring the Life and Legacy of Oliver P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks THE BAT FAUNA OF COSTA RICA’s RESERVA NATURAL ABSOLUTA CABO BLANCO AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR BAT CONSERVATION LA FAUNA DE MURCIÉLAGOS EN LA RESERVA NATURAL ABSOLUTA CABO BLANCO (COSTA RICA) Y SUS IMPLICACIONES EN LA CONSERVACIÓN DE LA QUIROPTEROFAUNA robert M. timm and Deedra K. McClearn ABSTRACT reserva Natural absoluta Cabo Blanco, located at the southern tip of northwestern Costa rica’s Nicoya Peninsula, was established in 1963 and is the country’s oldest nationally protected reserve. Because the climate of the Nicoya Peninsula is ideal for human habitation, the peninsula has been occupied for millennia and is a heavily impacted landscape. the region also is one of the most poorly studied in Central america in terms of biotic diversity. We initiated a multiyear survey of bats in the reserve and the adjacent Refugio de Vida Silvestre Cueva Los Murciélagos to quantify species diversity, abundances, habitat use, seasonality, and reproduction. By surveying bats during 5 rainy seasons and 4 dry seasons from July 1999 through February 2006, we address the following questions: Which species of bats are present in the area? are the bat communities the same in 3 different habitats—coastal forest, inland forest, and limestone caves? Are the species diversity and abundances of bats in the rainy season similar to those in the dry season? Can we discern seasonal patterns of reproduction? are the species diversity and abundances of bats at Cabo Blanco (a tropical moist forest in the Holdridge Life Zone classification) similar to those in the nearby tropical dry forest at Parque Nacional Palo Verde? What are the conservation implications of the bat assemblages found in this regenerating forest? Using mist nets, searching for roosting bats, and an acoustical survey, 39 species of bats are documented in the area, including 5 emballonurids, 4 molossids, 1 mormoopid, 1 noctilionid, 21 phyllostomids, and 7 vespertilionids. -

Genetic History and Pre-Columbian Diaspora of Chibchan Speaking Populations: Molecular Genetic Evidence

Genetic history and pre-Columbian Diaspora of Chibchan speaking populations: Molecular genetic evidence by Copyright 2008 Phillip Edward Melton M.A., University of Kansas, 2005 Submitted to the Department of Anthropology and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________ Chairperson _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ Date Defended:_________________________ The Dissertation Committee for Phillip E. Melton certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Genetic history and pre-Columbian Diaspora of Chibchan speaking populations: Molecular genetic evidence by Copyright 2008 Phillip Edward Melton M.A., University of Kansas, 2005 Submitted to the Department of Anthropology and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________ Chairperson _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ Date Defended:_________________________ ii Abstract This dissertation examined Y-Chromosome and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) genetic variation in 230 individuals from five (Rama, Chorotega, Huetar, Maléku, and Guaymi) indigenous populations inhabiting lower Central America in order to determine the evolutionary history and biological relationship among Chibchan-speakers and