Wealth and Hierarchy in the Intermediate Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Costa Rica

TWO NEW SPECIES OF FREZIERA (Pentaphylacaceae) FROM Costa RICA DANIEL SANTAMARÍA-AGUILAR,1,2 ALEX K. MONRO,3 QUÍRICO JIMÉNEZ-MADRIGAL,4 AND LAURA P. LAGOMARSINO5 Abstract. Two new species of Freziera endemic to Costa Rica, F. tarariae from the Cordillera de Talamanca and F. bradleyi from the Cordillera Central, are described and illustrated. Their distribution, phenology, habitat, and relationship to allied species are discussed. Resumen. Se describen e ilustran dos nuevas especies de Freziera endémicas de Costa Rica: Freziera tarariae de la Cordillera de Talamanca y Freziera bradleyi de la Cordillera Central. Se discuten sus afinidades, distribución, fenología y hábitat. Keywords: Cordillera Central, Ericales, Mesoamerica, Talamanca, Theaceae Freziera Willd. (Pentaphylacaceae) is a genus of ca. 57 margins. Leaves begin in a rolled terminal bud, and in some trees and shrubs distributed from Mexico to Bolivia and in cases a vernation scar or line remains on the undersurface the Antilles, with the highest species diversity in the Andes of the leaf lamina at maturity. At senescence, the leaves turn mountains of western South America (Mabberley, 2008; red. The flowers are 5-merous with an urceolate corolla Weitzman, 1987; Weitzman et al., 2004). Including the with pale petals that are connate or free at their base. The species described here, ten species of Freziera are known pedicels have a pair of bracteoles at their apex. The fruit is a from Mesoamerica, eight of which occur in Costa Rica. berry bearing many foveolate seeds. Most Mesoamerican species are restricted to cloud forests, During the preparation of the treatment of Freziera for where they are associated with disturbed habitats including the Manual de Plantas de Costa Rica, two undescribed roadsides, steep slopes, and mountain peaks. -

Distritos Declarados Zona Catastrada.Xlsx

Distritos de Zona Catastrada "zona 1" 1-San José 2-Alajuela3-Cartago 4-Heredia 5-Guanacaste 6-Puntarenas 7-Limón 104-PURISCAL 202-SAN RAMON 301-Cartago 304-Jiménez 401-Heredia 405-San Rafael 501-Liberia 508-Tilarán 601-Puntarenas 705- Matina 10409-CHIRES 20212-ZAPOTAL 30101-ORIENTAL 30401-JUAN VIÑAS 40101-HEREDIA 40501-SAN RAFAEL 50104-NACASCOLO 50801-TILARAN 60101-PUNTARENAS 70501-MATINA 10407-DESAMPARADITOS 203-Grecia 30102-OCCIDENTAL 30402-TUCURRIQUE 40102-MERCEDES 40502-SAN JOSECITO 502-Nicoya 50802-QUEBRADA GRANDE 60102-PITAHAYA 703-Siquirres 106-Aserri 20301-GRECIA 30103-CARMEN 30403-PEJIBAYE 40104-ULLOA 40503-SANTIAGO 50202-MANSIÓN 50803-TRONADORA 60103-CHOMES 70302-PACUARITO 10606-MONTERREY 20302-SAN ISIDRO 30104-SAN NICOLÁS 306-Alvarado 402-Barva 40504-ÁNGELES 50203-SAN ANTONIO 50804-SANTA ROSA 60106-MANZANILLO 70307-REVENTAZON 118-Curridabat 20303-SAN JOSE 30105-AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 30601-PACAYAS 40201-BARVA 40505-CONCEPCIÓN 50204-QUEBRADA HONDA 50805-LIBANO 60107-GUACIMAL 704-Talamanca 11803-SANCHEZ 20304-SAN ROQUE 30106-GUADALUPE O ARENILLA 30602-CERVANTES 40202-SAN PEDRO 406-San Isidro 50205-SÁMARA 50806-TIERRAS MORENAS 60108-BARRANCA 70401-BRATSI 11801-CURRIDABAT 20305-TACARES 30107-CORRALILLO 30603-CAPELLADES 40203-SAN PABLO 40601-SAN ISIDRO 50207-BELÉN DE NOSARITA 50807-ARENAL 60109-MONTE VERDE 70404-TELIRE 107-Mora 20307-PUENTE DE PIEDRA 30108-TIERRA BLANCA 305-TURRIALBA 40204-SAN ROQUE 40602-SAN JOSÉ 503-Santa Cruz 509-Nandayure 60112-CHACARITA 10704-PIEDRAS NEGRAS 20308-BOLIVAR 30109-DULCE NOMBRE 30512-CHIRRIPO -

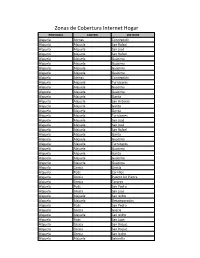

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

The Prehistoric Civilizations of Nuclear America GORDON R

The Prehistoric Civilizations of Nuclear America GORDON R. WILLEY H mwd University INTRODUCTION HE native agricultural civilizations of the New World had their begin- Tnings and their highest development in those areas that have been sub- sumed under the term “Nuclear America” (Kroeber 1948: 779). The desig- nation has both a geographical and a cultural connotation. The areas involved embrace central and southern Mexico, Central America, the north Andes, and Peru. This is the axis of aboriginal high culture in the Americas and, as such, the major center of prehistoric diffusion for the western hemisphere. To the best of our knowledge, it stands clearly apart and essentially independent from the comparable culture core of the Old World. Kroeber (1948: 784-85; 1952:377-95) has suggested the analogy between the American civilizational nucleus of Mexico-Peru and the “Oikoumene” of the Old World. Readapting the old Greek concept of the “inhabited” or civil- ized world (Kroeber 1952:379 and 392), he has defined the Oikoumene for purposes of culture-historical analysis as (‘ . the millennially interrelated higher civilizations in the connected mainland masses of the Eastern hemi- sphere,” and “as ’a great web of culture growth, areally extensive and rich in content.” It is, in effect, a vast diffusion sphere (see Hawkes 1954) interlinked across continents by common cultural content. The comparison with Nuclear America seems particularly apt. In both cases the great historic nexuses have considerable time depth at their centers, and in both they have influenced those cultures marginal to them at relatively later points on the time scale. -

Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia

This is an extract from: Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia Jeffrey Quilter and John W. Hoopes, Editors published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2003 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html The Political Economy of Pre-Colombian Goldwork: Four Examples from Northern South America Carl Henrik Langebaek Universidad de los Andes Introduction: The Problem ome twenty years ago, Alicia Dussán de Reichel (1979: 41) complained that studies that “set out to place the prehistoric metallurgy of Colombia within a wider context Sof cultural development” were not very numerous. Despite a great deal of research on Pre-Columbian goldwork since, the same observation remains true today. One source of frustration comes from the fact that most archaeologists focus on the study of metallurgy as a goal in itself. Although researchers have produced detailed descriptions about the techno- logical characteristics of Pre-Columbian goldwork (Scott 1981), timelines, definitions of “styles” and “traditions,” as well as correlations among styles across Colombia, Lower Central America, and Ecuador (Bray 1981; 1992a; 1997; Plazas and Falchetti 1983), and identifica- tions of plant and animal species represented in ornaments (Legast 1987), they have rarely placed goldwork within a social context (Looper 1996) or incorporated it in models related to social change. Whatever improvement in the research on Pre-Columbian metal objects there has been, further progress will be limited if it is not aimed at understanding the way societies function and change (Lechtman 1984). -

Secretaría Del Concejo Municipal Telefono / Fax 2236-7887 / 2236-8111 Ext 109 Moravia, Costa Rica

1YJL UJ. Tíl^ilM. SÍJLJMJLSSJL'S SECRETARÍA DEL CONCEJO MUNICIPAL TELEFONO / FAX 2236-7887 / 2236-8111 EXT 109 MORAVIA, COSTA RICA de:enerp^-200r5CMM 027-01-09 \';:,: . FEF. ACDO. 1726 Lie. Edgar Vargas Jiménez Alcalde Municipal Moravia Estimado señor: -I-'. Para su información y fines'pertinentéslé remito ei siguiente acuerdo tomado por el Concejo Municipal de Moravia: MOCIÓN DELJ ALCALDE LIC. EDGAR VARGAS -^ ACUERDO 1726; 1. Con dispensa de trámite » , £ • Nuestro cajntón se encuentra ubicado en una reglón del Valle Central que goza de un agradable clima y fértiles tierras. Estas particularidades hicieron que Moravia se formara como un pijieblo netamente de agricultores, comprometidos a trabajar la tierra. Lo cual fue el paso qué antiguamente propició el progreso del Cantón. • Nuestros ajgricultores han demostrado sabiamente a través de cientos de años, que se puede producir sin necesidad de recurrir a semillas que hayan sido sometidas a algún tipo de modificación genética, (semillas transgénicas) i : • La semilla fde achiote (Bixa orellana) ocupa ,un lugar importante dentro t3e la memoria histórica de nuestros ancestros. Precisamente por ello Moravia es conocida como el "pueblo délos achioteros". • Moravia además cuenta con una impresionante biodiversidad, ejemplo de lo anterior es que una parte de nuestro cantón constituye el Parque Nacional Braulio Carrillo, el cual queremos proteger para el disfrute de las futuras generaciones. Esta Municipalidad se compromete a [impulsar la agricultura orgánica, las buenas prácticas ambiéntale los sistemas de producción limpios, el manejo eficiente de los desechos sólidos, el turismo responsable y sostenible, la protección de los bosques, los cuerpos de agua y la :auna silvestre. -

Codebook for 40983343Costa Rica 2004 Export Version Pais PAIS 6

Codebook for 40983343costa rica 2004 export version pais PAIS 6 cridnum Número de entrevista crprov Provincia 1 San José 2 Alajuela 3 Cartago 4 Heredia 5 Guanacaste 6 Puntarenas 7 Limón crcant Cantón crcantr 101 San José 102 Escazú 103 Desamparados 104 Puriscal 106 Aserrí 108 Goicoechea 109 Santa Ana 110 Alajuelita 113 Tibás 115 Montes de Oca 119 Pérez Zeledón 201 Alajuela 202 San Ramón 203 Grecia 208 Poás 210 San Carlos 301 Cartago 305 Turrialba 307 Oreamuno 401 Heredia 407 Belén 410 Sarapiquí 505 Carrillo 510 La Cruz 601 Puntarenas 611 Garabito 701 Limón 702 Pococí 706 Guácimo crdist Distrito crdistr 10104 Catedral 10106 San Francisco de Dos Ríos 10107 Uruca 10109 Pavas 10110 Hatillo 10111 San Sebastián 10201 Escazú 10202 San Antonio 10203 San Rafael 10301 Desamparados 10303 San Juan de Dios 10307 Patarrá 10311 San Rafael Abajo 10401 Santiago 10408 San Antonio 10409 Chires 10601 Aserrí 10607 Salitrillos 10801 Guadalupe 10803 Calle Blancos 10804 Mata de Pl tano 10805 Ipís 10901 Santa Ana 10903 Pozos 10904 Uruca 10905 Piedades 11001 Alajuelita 11002 San Josecito 11004 Concepción 11005 San Felipe 11301 San Juan 11303 Anselmo Llorente 11304 leon XIII 11501 San Pedro 11503 Mercedes -Betania- 11504 San Rafael 11901 San Isidro de El General 11904 Rivas 11906 Platanares 11909 Barú 20101 Alajuela 20112 Tambor 20113 Garita 20201 San Ramón 20204 Piedades Norte 20206 San Rafael 20208 Angeles 20301 Grecia 20304 San Roque 20308 Bolívar 20801 San Pedro 20802 San Juan 20804 Carrillos 21001 Quesada 21005 Venecia 21006 Pital 30103 Carmen 30105 Aguacaliente -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

La Amenaza Sísmica En La Zona De Cartago

INSTITUTO COSTARRICENSE ELECTRICIDAD UEN PROYECTOS Y SERVICIOS ASOCIADOS C.S. EPLORACIÓN SUBTERRÁNEA La amenaza sísmica en la zona de Cartago Por: Geól. Rafael Barquero P. ÁREA AMENAZAS Y AUSCULTACIÓN SÍSMICA Y VOLCÁNICA Mayo 2010 Introducción Tal y como ha sido identificado en diversos estudios e informes (Aguilar, 1980, Salazar et al., 1992; Alvarado & Boschini, 1988, Fernández & Montero, 2002, Montero et al. 2005), Cartago se encuentra localizada en un área sísmicamente activa y localmente caracterizada por la existencia de fallas activas y potencialmente activas. Aunado a ello tenemos la presencia de laderas inestables, en las cuales son frecuentes los deslizamientos. Por todo lo anterior, el área se considera como muy vulnerable a los terremotos. Localmente, los daños asociados con la ocurrencia de un evento sísmico pueden ser el resultado de los efectos directos de la ruptura en superficie de fallas, o más probablemente debido a los efectos de la sacudida sísmica del suelo (propagación de las ondas sísmicas). Sin embargo, efectos secundarios relacionados con la sacudida sísmica, como lo es el comportamiento del suelo (deslizamientos y compactación de sedimentos), son los que preocupan más y pueden ser potenciales generadores de daños. En el presente estudio, se realizó una revisión de la información sismológica. Para ello se utilizaron los datos que se tienen de la Red Sismológica Nacional, así como los nuevos aportes al conocimiento de la tectónica de la región de los últimos 25 años. Este estudio tiene como objetivo primordial, estimar las características de la sacudida sísmica en la zona de Cartago por la ocurrencia futura de sismos severos. Sismicidad histórica Dentro de la zona de Cartago se han presentado varios terremotos importantes durante los siglos XIX y XX (Cuadro 1, Fig. -

301 Zonashomogeneas Distrito

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 3 CARTAGO CANTÓN 01 CARTAGO DISTRITO 05 AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 506200 511200 516200 521200 a l l i n R e ío r To A y o Mapa de Valores de Terrenos ORIENTAL gr Oreamuno a e i s u OCCIDENTAL q Súper Mas e SAN RAFAEL c A Q GUADALUPE O ARENILLA BARRIO PITAHAYA por Zonas Homogéneas u Antiguo Matadero Municipal e 3 01 05 R03/U03 b Salón comunal r RESIDENCIAL CARTAGO - BARRIO CERRILLOS - SAN LUIS GONZAGA a d R 3 01 05 U04 a ESCUELA PITAHAYA í o Provincia 3 Cartago L MANUEL DE JESUS JIMENEZ u 3 01 05 U02 C æ s 3 01 05 U06 o ia nm r i SANTIAGO s VALLE DEL PRADO - RESIDENCIALnm LAS GARZAS - VEREDAS DEL CONQUISTADOR 3 01 05 U07 Cantón 01 Cartago Avenida 38A CIUDAD DE ORO LLANOS DE SANTA LUCÍA 3 01 05 U27 A 7 o VILLAS DEL SOL - EL CASTILLO r Distrito 05 Aguacaliente o e r l e Teja 3 01 05 U26 l u A a EL TEJAR Cementerio rq C a EscuelaHACIENDA DE ORO HACIENDA REAL B nm ío 3 01 05 U11 3 01 05 U13 San Francisco nm R R 1088400 nm 1088400 COCORI AGUACALIENTE - RESIDENCIAL SAN FRANCISCO í o 3 01 05 U10 nm 3 01 05 U12 JARDINES DE AGUACALIENTE B l a 3 01 05 U24 q u E VALLE VERDE A i A ven TOBOSI A ida 60 l l PARAÍSO T CIUDAD DE LOS NIÑOS 0 o eja LA CAMPIÑA 3 01 05 R14/U14 e r l 3 01 05 U30 3 01 05 R25/U25 l Adepea a 4 enida 6 GUAYABAL Campo de Aterrizaje C Av 3 01 05 U23 nm 2 Presa Q 6 ue Orfanato Salón Comunal b a ra d Hervidero R da i Ruta N n a ciona í G l 231Poblado Barro Morado o ua e v ya A b A a g Llanos de Lourdes FABRICA DE CEMENTO HOLCIM u 3 01 05 R17/U17 a Ministerio de Hacienda C LLANOS DE LOURDES a l i 3 01 05 U16 e n Órgano de Normalización Técnica A San CONDOMINIO EL TEJALæ t Isidro nm e 3 01 05 U29 CACHÍ R BARRO MORADO - NAVARRO ío s C jo 3 01 05 R18/U18 n h ra ir a í N os Guatuso L le al C Cerro Lucosal l Platanillo a j a c s a C a d a r GUATUSO - RIO NAVARRO b to e ri 3 01 05 R19/U19 u r a Q v a N Finca Trinidad ío R Navarrito 1083400 1083400 rro ava Aprobado por: N Q ío Muñeco R u e Iglesia Católica Navarro del Muñeco b r Plaza deæ Deportes a nm d a R o j PEJIBAYE a s Ing. -

Derived Flood Assessment

30 July 2021 PRELIMINARY SATELLITE- DERIVED FLOOD ASSESSMENT Alajuela Limon, Cartago, Heredia and Alajuela Provinces, Costa Rica Status: Several areas impacted by flooding including agricultural areas and road infrastructure. Increased water levels also observed along rivers. Further action(s): continue monitoring COSTA RICA AREA OF INTEREST (AOI) 30 July 2021 PROVINCE AOI 6, Los Chiles AOI 5, Sarapiqui AOI 3, Matina AOI 2, Limon AOI 4, Turrialba AOI 1, Talamanca N FLOODS OVER COSTA RICA 70 km NICARAGUA AOI 6, Los Chiles Satellite detected water as of 29 July 2021 AOI 5, Sarapiqui AOI 3, Matina Canton AOI 2, Limon City AOI 4, Turrialba Caribbean Sea North Pacific Ocean AOI 1, Talamanca Legend Province boundary International boundary Area of interest Cloud mask Reference water PANAMA Satellite detected water as of 29 July 2021 [Joint ABI/VIIRS] Background: ESRI Basemap 3 Image center: AOI 1: Talamanca District, Limon Province 82°43'56.174"W Limon Province 9°34'12.232"N Flood tracks along the Sixaola river observed BEFORE AFTER COSTA RICA Flood track COSTA RICA Flood track Sixaola river Sixaola river PANAMA PANAMA Sentinel-2 / 19 June 2021 Sentinel-2 / 29 July 2021 4 Image center: AOI 2: Limon City, Limon District, Limon Province 83°2'54.168"W Limon Province 9°59'5.985"N Floods and potentially affected structures observed BEFORE AFTER Limon City Limon City Potentially affected structures Evidence of drainage Increased water along the irrigation canal N N 400 400 m m Sentinel-2 / 19 June 2021 Sentinel-2 / 29 July 2021 5 Image center: AOI -

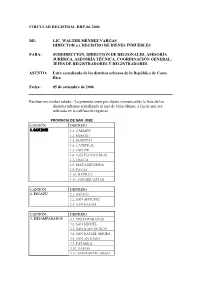

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9.