State Building and Repression in Authoritarian Onset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRISSON: the Collected Criticism of Alice Guillermo

FRIS SON: The Collected Criticism of Alice Guillermo Reviewing Current Art | 23 The Social Form of Art | 4 Patrick D. Flores Abstract and/or Figurative: A Wrong Choice | 9 SON: Assessing Alice G. Guillermo a Corpus | 115 Annotating Alice: A Biography from Her Bibliography | 16 Roberto G. Paulino Rendering Culture Political | 161 Timeline | 237 Acknowledgment | 241 Biographies | 242 PCAN | 243 Broadening the Public Sphere of Art | 191 FRISSON The Social Form of Art by Patrick D. Flores The criticism of Alice Guillermo presents an instance in which the encounter of the work of art resists a series of possible alienations even as it profoundly acknowledges the integrity of distinct form. The critic in this situation attentively dwells on the material of this form so that she may be able to explicate the ecology and the sociality without which it cannot concretize. The work of art, therefore, becomes the work of the world, extensively and deeply conceived. Such present-ness is vital as the critic faces the work in the world and tries to ramify that world beyond what is before her. This is one alienation that is calibrated. The work of art transpiring in the world becomes the work of the critic who lets it matter in language, freights it and leavens it with presence so that human potential unerringly turns plastic, or better still, animate: Against the cold stone, tomblike and silent, are the living glances, supplicating, questioning, challenging, or speaking—the eyes quick with feeling or the movements of thought, the mouths delicately shaping speech, the expressive gestures, and the bodies in their postures determined by the conditions of work and social circumstance. -

3Rd Urban Greening Forum Presentor: Armando M

Urban Forestry in the Philippines Armando M. Palijon, Ludy Wagan, Antonio Manila 13-15 September 2017, Seoul, Republic of Korea UF in Phil- very political in nature Always a fresh start but not a continuation of what has been started UF and related Programs Administration/Presidency Program for Forest Ecosystem Pres Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Management (ProFEM Luntiang Kamaynilaan Program (LKP) Pres Corazon C. Aquino Master Plan for Forest Development Clean and Green Program (CGP) Pres Fidel V. Ramos ---- Pres Joseph Estrada Luntiang Pilipinas Program (LPP) Senator Loren Legarda ---- Pres Gloria Macapagal Green Pan Philippine Highway Former DENR Sec Angelo Reyes National Greening Program Pres Benigno Aquino Jr. Expanded National Greening Program Pres Rodrigo Duterte The First Forum Harmonizing Urban Greening in Metro Manila Sustainable Green Metro Manila Armando M. Palijon Professor IRNR-CFNR-UPLB Urban Forestry Forum Splash Mountain, Los Banos, Laguna June 17-18, 2014 Rationale of the Forum Background - Need for making Metro Manila Sustainably Green - Metro Manila to be at par with ASEAN neighbors Basic concern How? - All 16 cities & a municipality in MM to have common vision and mission in harmonizing development and urban renewal with environmental conservation -Urban greening & re-greening the way forward -Balance between built-up areas and greenery The Second Forum Delved on: -Mission & vision Presentation of the -Organization- offices/units in charge of greening greening program of -Capabilities in terms of: +Manpower (expertise/ skills) MMDA and MM’s LGUs +Technology, tools, equipment & supplies +Facilities -Local laws, ordinances -Available areas for greening Highlighted by a workshop aimed at harmonizing MM greening plan MM Urban Greening Plan 3rd Urban Greening Forum Presentor: Armando M. -

Beyond Boxers Or Briefs Educate Early, Vote Often by Joshua Levy an Interview with Civicyouth.Org’S Peter Levine Letters to the Editor

CHAPTER NEWS MEMBER NEWS AND MORE TVNNFS 2008 :PVOH7PUFST "DUJWJTUTBSF3FBEZUPCF)FBSE .JTTJPOUP.BOHV[J QH $BMMFEUP"GSJDB 8F'PVOE0VSTFMWFT CZ#SJDF/JFMTFO 04 .FNPJSTPGB4USFFU.BSDIFS QH 12 .Z"DUJWJTNJO3FUSPTQFDU CZ+PTF%BMJTBZ+S #FZPOE#PYFSTPS#SJFGT "DUJWJTU 5FDI8BUDIFS+PTIVB-FWZ QH 14 5BDLMFT/FX.FEJBBOE1PMJUJDT &EVDBUF&BSMZ 7PUF0GUFO $SVODIJOHUIF/VNCFST QH 18 XJUI$*3$-&µT1FUFS-FWJOF The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the staff of Phi Kappa Phi Forum or the Board of Directors of The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi. phi kappa phi forum (issn 1538-5914) is published quarterly by The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, 7576 Goodwood Blvd., Baton Rouge, la 70806. Printed at R.R. Donnelley, 1160 N. Main, Pontiac, il 61764. the honor society of phi kappa phi was founded in ©The Honor Society of Phi 1897 and became a national organization through the Kappa Phi, 008. All rights efforts of the presidents of three state universities. Its reserved. Non-member primary objective has from the first been the recognition subscriptions $30 per and encouragement of superior scholarship in all fields of year. Single copies $10 study. Good character is an essential supporting attribute each. Periodicals postage for those elected to membership. The motto of the Society paid Baton Rouge, la and additional mailing is phiosophia krateito phótón, which is freely translated as offices. Material intended “Let the love of learning rule humanity.” for publication should be Phi Kappa Phi encourages and recognizes academic addressed to Traci Navarre, excellence through several programs. Through its The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, 7576 Goodwood awards and grants programs, the Society each triennium Blvd., Baton Rouge, la 70806. -

ANG Expand and Strengthen the Protest Movement Against Aquino's

Pahayagan ng Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas ANG Pinapatnubayan ng Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo English Edition Vol. XLIV No. 17 September 7, 2013 www.philippinerevolution.net Editorial Expand and strengthen the protest movement against Aquino's corruption he huge August 26 demonstration at the Luneta Park in Manila the broad masses of the people. and various other places here and abroad was an indicator of It now faces the widespread Tthe Filipino people's widespread anger at the pork barrel sys- hatred of the middle strata of tem. Through this protest, the people demonstrated their wrath at professionals, teachers and oth- the bureaucratic plunder of public funds and their use by the ruling er employees, doctors, nurses Aquino regime to dominate reactionary politics. and health workers, church peo- ple and lawyers. All of them The pork barrel issue has their apathy at the glaring gap were at the receiving end of further laid bare the ruling between their affluence and the Aquino's attempts to entice classes' greed and underscored hard, deprived and wretched them with propaganda on re- their deliberate refusal to heed lives of the toiling masses. form and good governance. the people's grievances and Only at the middle of its six- The huge protest action and year term, continually expanding move- the Aquino ment against the pork barrel regime is now comprise an important leap in severely iso- the widespread participation of lated from ordinary folk in political action. The people's burgeoning an- ger is rooted in the deepening and expanding socio-economic In this issue... Protests greet key US officials 5 Raid and ambush in ComVal and Agusan Sur 8 Antimining datu in Davao del Sur killed 11 crisis. -

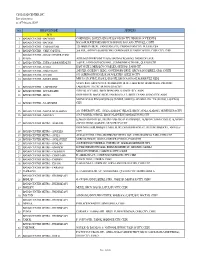

CIS BAYAD CENTER, INC. List of Partners As of February 2020*

CIS BAYAD CENTER, INC. List of partners as of February 2020* NO. BRANCH NAME ADDRESS BCO 1 BAYAD CENTER - BACOLOD COKIN BLDG. LOPEZ JAENA ST.,BACOLOD CITY, NEGROS OCCIDENTAL 2 BAYAD CENTER - BACOOR BACOOR BOULEVARD, BRGY. BAYANAN, BACOOR CITY HALL, CAVITE 3 BAYAD CENTER - CABANATUAN 720 MARILYN BLDG., SANGITAN ESTE, CABANATUAN CITY, NUEVA ECIJA 4 BAYAD CENTER - CEBU CAPITOL 2nd FLR., AVON PLAZA BUILDING, OSMENA BOULEVARD CAPITOL. CEBU CITY, CEBU BAYAD CENTER - DAVAO CENTER POINT 5 PLAZA ATRIUM CENTERPOINT PLAZA, MATINA CROSSING, DAVAO DEL SUR 6 BAYAD CENTER - EVER COMMONWEALTH 2ndFLR., EVER GOTESCO MALL, COMMONWEALTH AVE., QUEZON CITY 7 BAYAD CENTER - GATE2 EAST GATE 2, MERALCO COMPLEX, ORTIGAS, PASIG CITY 8 BAYAD CENTER - GMA CAVITE 2ND FLR. GGHHNC 1 BLDG., GOVERNORS DRVE, BRGY SAN GABRIEL, GMA, CAVITE 9 BAYAD CENTER - GULOD 873 QUIRINO HWAY,GULOD,NOVALICHES, QUEZON CITY 10 BAYAD CENTER - KASIGLAHAN MWCI.SAT.OFFICE, KASIGLAHAN VIL.,BRGY.SAN JOSE,RODRIGUEZ, RIZAL SPACE R-O5 GROUND FLR. REMBRANDT BLDG. LAKEFRONT BOARDWALK, PRESIDIO 11 BAYAD CENTER - LAKEFRONT LAKEFRONT, SUCAT, MUNTINLUPA CITY 12 BAYAD CENTER - LCC LEGAZPI 4TH FLR. LCC MALL, BRGY.DINAGAAN, LEGASPI CITY, ALBAY 13 BAYAD CENTER - LIGAO GROUND FLR. MA-VIC BLDG, SAN ROQUE ST., BRGY. DUNAO, LIGAO CITY, ALBAY MAYNILAD LAS PIÑAS BUSINESS CENTER, MARCOS ALVAREZ AVE. TALON UNO, LAS PIÑAS 14 BAYAD CENTER - M. ALVAREZ CITY 15 BAYAD CENTER - MAYNILAD ALABANG 201 UNIVERSITY AVE., AYALA ALABANG VILLAGE, BRGY. AYALA ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY 16 BAYAD CENTER - MAYSILO 479-F MAYSILO CIRCLE, BRGY. PLAINVIEW, MANDALUYONG CITY LOWER GROUND FLR., METRO GAISANO SUPERMARKET, ALABANG TOWN CENTER, ALABANG- 17 BAYAD CENTER METRO - ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD, ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY GROUND FLOOR,MARQUEE MALL BLDG, DON BONIFACIO ST., PULUNG MARAGUL, ANGELES 18 BAYAD CENTER METRO - ANGELES CITY 19 BAYAD CENTER METRO - AYALA AYALA CENTER, CEBU ARCHBISHOP REYES AVE., CEBU BUSINESS PARK, CEBU CITY 20 BAYAD CENTER METRO - AYALA FELIZ MARCOS HI-WAY, LIGAYA, CORNER JP RIZAL, PASIG CITY 21 BAYAD CENTER METRO - BANILAD A.S FORTUNA CORNER H. -

News Monitoring 12 10 2019

12 -10-le DATE DAY Tuesday ID Nom irsants Strategic Conuriunication and Imitative Service • STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION UPPER PAGE I BANNER EDITORIAL CARTOON STORY STORY INITIATIVES be, PAGE tO ER SERVICE BusinessMirror Al ir I •Pm N2- lo -1G TITLE: PAGE I/ DATE Nationwide ban on single-use plastic out soon—DENR exec HE Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) is finalizing an order that will impose a nationwide ban on single- Tuse plastics to help address the problem brought about by plastic pollution, officials said; DENR Undersecretary for Solid Waste Management Benny D. Anti- porda said the DENR's Executive Committee (Execom) has yet to come up with a final decision. "We will still discuss this at the Execom level: Antiporda, who also headstheNationalSolidWasteManagementCommission (NSWMC), said. The DENRoffidal said the order willbe handed down soonby the DENR chief as part of the agency's ongoing efforts to rehabilitate Manila Bay and some of the country's tourist spots which started last year in the world- renowned Boracay Island in the Municipality of Malay, Aklan province. Ahead of the policy issuance prohibiting the use of single-use plastics, the DENR-Mimaroparegionandthe Municipalityof Puerto Galerain Ori- ental Mindoro have recently signed a memorandum of agreement (MOA) establishing the Municipality as a local chapter of Tayo ang Kalikasan (TAK), the DENR's advocacy that aims to engage communities as part- ners in addressing issues and challenges on environmental protection. The MOA signing held on December 7, 2019, coincided with the cel- ebration of the 92nd Founding Anniversary of Puerto Galera. The MOA was signed and witnessed by national and local officials led by Puerto Galera Mayor Rocky Ilagan, Vice Mayor Marlon Lopez, and Oriental Mindoro Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Officer Mary June Maypa and Provincial Environment Management Officer Ederlita Labre, representingDENR-MimaropaRegionalExecutive Director Henry Adornado and EnvironmentalManagement Bureau-MimaropaRegional Director Atty. -

Tourism Potential from Riverbank Development and River Clean Up

BY: CYNTHIA C. LAZO DIRECTOR TOURISM PLANNING AND PROMOTIONS DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM Pasig River Forum - Asian Development Bank 24 April 2012 Fort Santiago* Location: Intramuros, Manila (NCR) Category: Structure Type: Fortification Status: National Shrine Marker Date: 1934, 1972 (Declaration) Marker Text: Ang Pagpapalaya ng Maynila Ang Pagpapalaya ng Maynila Location: Postigo St., Intramuros, Manila (Region NCR) Category: Site Type: Site Status: Level II - With Marker Marker Date: February 3, 1989 Fort Santiago Memorial Location: Intramuros, Manila (Region NCR) Category: Structure Type: Memorial Status: Level II - With Marker Marker Date: 1995 Ang Akwaryum Marker Text: ANG AKWARYUM ANG HUGIS BAGONG BUWAN AY DIINIBUHO NI INHINYERO MIGUEL ANTONIO GOMEZ BILANG BAHAGI NG TANGGULAN NG MAYNILA AT NATA POS NOONG 1771. DAHIL SA KINALALAGYAN NGAYON NG BAGUMBAYAN KAYA'T PINANGANLANG "REVELLIN" NG BAGUMBAYAN. NOONG 1780, ANG PUERTA REAL AY INILIPAT SA PAGITAN NG MGA KUTANG SAN ANDRES AT SAN DIEGO, BUHAT SA DAKONG TIMOG NG DAANG Location: Gen. Luna St., Intramuros, PALACIO, NA NAGING DAANG HENERAL LUNA. SAPAGKA'T ANG DAANG PATUNGONG PUERTA REAL AY NAGLALAGOS SA ILALIM NG HUGIS BAGONG BUWAN, KAYA'T ANG Manila (Region NCR) DATING "REVELLIN" NG BAGUMBAYAN AY PINALITAN NG "REVELLIN" NG PUERTA Category: Structure REAL. NOONG 1902, ANG MOOG NG LUNGSOD AY BINUKSAN SA DAKONG TIMOG NG DAANG HENERAL LUNA AT ANG PUERTA REAL AY IPININID. NAGKAROON NG MGA Type: Aquarium PAG-BABAGO AT ITO'Y GINAWANG AKWARYUM. NAWASAK ANG BAHAGI NG AKWARYUM AT "REVELLIN" NOONG PEBRERO 1945 NANG MAGHAMOK ANG MGA Status: Level II - With Marker AMERIKANO AT HAPON. MULING NIYARI ANG AKWARYUM NOONG PEBRERO 1968 SA Marker Date: 1968 PAGSISIKAP NG ZONTA CLUB NG MAYNILA. -

MEMORANDUM for DMCI PROJECT DEVELOPERS, INC. to Love One’S City, and Have a Part in Its Advancement and Improvement, Is the Highest Privilege and Duty of a Citizen

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SUPREME COURT MANILA En Banc G.R. No. 213948 KNIGHTS OF RIZAL Petitioner - versus - DMCI HOMES, INC. ET AL. Respondents MEMORANDUM FOR DMCI PROJECT DEVELOPERS, INC. To love one’s city, and have a part in its advancement and improvement, is the highest privilege and duty of a citizen. – Daniel H. Burnham, architect and master planner of Manila REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SUPREME COURT MANILA En Banc KNIGHTS OF RIZAL, Petitioner, - versus - G.R. No. 213948 DMCI HOMES, INC. ET AL., Respondents. MEMORANDUM Private respondent DMCI Project Developers, Inc. (“DMCI-PDI”), by counsel, respectfully states: Prefatory In December 1913, the Jose Rizal National Monument (“Rizal Monument”) was erected on the Luneta as a tomb and a memorial to Jose Rizal. Since its creation in 1907 as the model entitled Motto Stella up to the present, more than a century hence, it has been mired in controversy. The stat- ue of Rizal was criticized as a poor depiction of the national hero, dressed like a European in an ill-fitting overcoat, while the monument itself, according to the Official Gazette web- site, “shies away from magnificence. It does not tower, there are no ornate details, no grandiose aesthetic claims.”1 For decades after its installation until 1961, it stood alone in an empty field. Then the Knights of Rizal, petitioner in this case (“petitioner”), successfully lobbied for the building of a Rizal Memorial Cultural Center at the back of the monument, which was never built. But a towering steel shaft that reached more than 30 meters was installed on the monument, until it was removed two years later after widespread censure. -

Cities in Film: Architecture, Urban Space and the Moving Image

Cities in Film: Architecture, Urban Space and the Moving Image An International Interdisciplinary Conference University of Liverpool, 26-28th March 2008 Conference Proceedings. This conference is organised by the School of Architecture and School of Politics and Communication Studies. The AHRC-funded research project, entitled City in Film: Liverpool's Urban Landscape and the Moving Image, is conducted by Dr Julia Hallam (principle investigator), Professor Robert Kronenburg (co-investigator), Dr Richard Koeck and Dr Les Roberts. This conference is supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the University of Liverpool. Cover design: Richard Koeck and Les Roberts. Copyright cover image: Angus Tilston. Edited by Julia Hallam, Robert Kronenburg, Richard Koeck and Les Roberts. Please note that authors are responsible for copyright clearance of images reproduced in the proceedings. Cities in Film: Architecture, Urban Space and the Moving Image An International Interdisciplinary Conference University of Liverpool, 26-28th March 2008 Cities in Film explores the relationship between film, architecture and the urban landscape drawing on interests in film, architecture, urban studies and civic design, cultural geography, cultural studies and related fields. The conference is part of University of Liverpool's contribution to the European Capital of Culture 2008, and aims to foster interdisciplinary dialogues around architectural and film history and theory, film and urban space, and to point towards new intellectual frameworks for discussion. It seeks to draw on the work of theorists and practitioners engaged in ideas in these areas, examining film in the context of urban design and development and exploring in particular the contested social, cultural and political terrain that underpins these practices. -

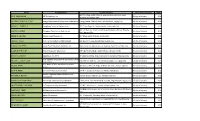

Name Establishment Location/Address Date of Accreditation YEAR JGC Phil

Name Establishment Location/Address Date of Accreditation YEAR JGC Phil. Bldg., 2109 Prime St. Madrigal Business Park, Ayala JAY R. KABAMALAN JGC Philippines, Inc. 5th day of January 2012 Alabang, Muntinlupa City ANTONIO FRANCIS G. CHUA Energy Development Corporation-Laboratory Energy Center, Merritt Road, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 5th day of January 2012 MANUEL L. EMBERGA Symphony Industrial Corporation 354 F. San Diego St., Viente Reales, Valenzuela City 5th day of January 2012 Quezon Institute Compound, Eulogio Rodriguez Avenue (España LUISITO A. ASIÑAS Philippine Tuberculosis Society, Inc. 5th day of January 2012 Ext.), Quezon City FERDIE P. DE LUNA Pascual Laboratories, Inc. 817 EDSA, South Triangle, Quezon City 5th day of January 2012 TOMAS T. BALISI Ann Francis Mother & Child Hospital 606 Quirino Hi-way, Novaliches, Quezon City 5th day of January 2012 RODOLFO M. REYES Green Earth Treatment Solutions, Inc. Elena Drive cor. Marcos Alvarez Avenue, Talon 5, Las Piñas City 5th day of January 2012 ALANE BLYTHE C. DY United Diagnostic Laboratory G/F UDL Medical Bldg., 1440 Taft Ave., Ermita, Manila 5th day of January 2012 JINARD A. MODINA Cargohaus, Inc. (CHI) 4F Cargohaus Bldg., Brgy. Vitalez, NAIA Complex, Parañaque City 5th day of January 2012 Blue Sapphire and Sapphire Residences Condo MICHAEL E. COSTELO, JR. 2nd Ave. cor. 30th St., Fort Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City 5th day of January 2012 Corporation First Medical Team Healthcare Specialist PAUL M. TEVES 4/F San Luis Terraces Bldg., 638 T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila 5th day of January 2012 Group ELMA P. REYES One Pacific Place Condominium 147 H.V. -

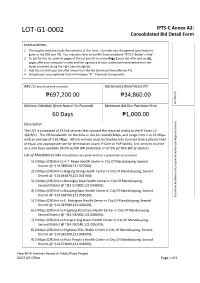

IPTS-C Annex A2: Consolidated Bid Detail Form

LOT-G1-0002 IPTS-C Annex A2: Consolidated Bid Detail Form Instructions: 1. Thoroughly read and study the contents of this form. Consider also the general specifications given in the BDS and ITB. You may also refer to the MS Excel workbook “IPTS-C Bidder’s Aide”. 2. To bid for this lot, print all pages of this lot and fill-in on the Page 1 your bid offer and on ALL pages affix your company’s name and the signature of your authorized representative in the boxes provided along the right hand margin(s). 3. Add this lot with your bid offer amount on the Bid Summary Sheet (Annex A1). 4. Include your accomplished form in Envelope "B" - Financial Components ABC (12-month service contract) Bid Security Bond Value (P) (P) ₱697,200.00 ₱34,860.00 Offer Delivery Schedule (from Notice-To-Proceed) Minimum Bid Doc Purchase Price Bid 60 Days ₱1,000.00 Description ) The LOT is composed of 23 link services that connect the required site(s) to the IP Core: L1- tative 1[A/B/C]. The CIR bandwidth for the links in this lot total 83 Mbps, and range from 2 to 23 Mbps with an average of 3.61 Mbps. All link services must be trunked into no more than 2 phycial links of equal and appropriate size for termination at any IP Core or PoP facility. Link services shall be on a 24H basis available 99.0% w/ NO BW protection or 97.9% w/ 50% BW protection. List of Mandatory Links (Coordinates are given without a guarantee of accuracy) 1) 2 Mbps (CIR) link to A.T. -

Talaan Ng Mga Nilalaman

TALAAN NG MGA NILALAMAN I. ANG PAMAHALAANG PAMBANSA A. SANGAY TAGAPAGPAGANAP Tanggapan ng Pangulo 3 Tanggapan ng Pangalawang Pangulo 6 Tanggapang Pampanguluhan sa Operasyong Pangkomunikasyon 7 Iba Pang Tanggapang Tagapagpaganap 9 Kagawaran ng Repormang Pansakahan 14 Kagawaran ng Agrikultura 17 Kagawaran ng Badyet at Pamamahala 22 Kagawaran ng Edukasyon 29 Kagawaran ng Enerhiya 34 Kagawaran ng Kapaligiran at Likas na Yaman 36 Kagawaran ng Pananalapi 41 Kagawaran ng Ugnayang Panlabas 44 Kagawaran ng Kalusugan 54 Kagawaran ng Teknolohiyang Pang-impormasyon at Komunikasyon 60 Kagawaran ng Interyor at Pamahalaang Lokal 62 Kagawaran ng Katarungan 66 Kagawaran ng Paggawa at Empleo 70 Kagawaran ng Tanggulang Pambansa 74 Kagawaran ng mga Pagawaing Bayan at Lansangan 77 Kagawaran ng Agham at Teknolohiya 80 Kagawaran ng Kagalingang Panlipunan at Pagpapaunlad 86 Kagawaran ng Turismo 91 Kagawaran ng Kalakalan at Industriya 94 Kagawaran ng Transportasyon 99 Pambansang Pangasiwaan sa Kabuhayan at Pagpapaunlad 102 Mga Tanggapang Konstitusyonal l Komisyon sa Serbisyo Sibil 109 l Komisyon sa Awdit 111 l Komisyon sa Halalan 114 l Komisyon sa Karapatang Pantao 116 l Tanggapan ng Tanodbayan 118 Mga Korporasyong Pag-aari at/o Kontrolado ng Pamahalaan 123 Mga Pampamahalaang Unibersidad at Kolehiyo 134 B. SANGAY TAGAPAGBATAS Senado ng Pilipinas 153 Kapulungan ng mga Kinatawan 158 C. SANGAY HUDIKATURA Kataas-Taasang Hukuman ng Pilipinas 173 Hukuman ng Apelasyon 174 Hukuman ng Apelasyon sa Buwis 176 Sandiganbayan 177 II. MGA PAMAHALAANG LOKAL Mga Pamahalaang Panlalawigan 181 Mga Pamahalaang Panlungsod 187 Mga Pamahalaang Pambayan 195 Rehiyong Awtonomo sa Muslim Mindanao 248 III. MGA MISYONG DIPLOMATIKO AT KONSULADO 255 IV. MGA AHENSIYA NG NAGKAKAISANG BANSA AT 283 IBA PANG PANDAIGDIGANG ORGANISASYON SANGAY TAGAPAGPAGANAP SANGAY TAGAPAGPAGANAP Ang Sangay Tagapagpaganap ay nagsasakatuparan ng mga pambansang patakaran at nagtataguyod ng mga tungkuling pang- ehekutibo at pampangasiwaan ng Pambansang Pamahalaan.