History in the Opening Sequence of Desperate Housewives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USA TODAY Life Section D Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Cover Story

USA TODAY Life Section D Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Cover Story: http://www.usatoday.com/life/people/2005-11-21-huffman_x.htm Felicity Huffman is sitting pretty: Emmy-winning Housewives star ignites Oscar talk for transsexual role By William Keck, USA TODAY By Dan MacMedan, USA TODAY Has it all: An actress for more than twenty years, Felicity Huffman has an Emmy for her role on hit Desperate Housewives, a critically lauded role in the film Transamerica, a famous husband (William H. Macy) and two daughters. 2 WEST HOLLYWOOD Felicity Huffman is on a wild ride. Her ABC show, Desperate Housewives, became hot, hot, hot last season and hasn't lost much steam. She won the Emmy in September over two of her Housewives co-stars. And now she is getting not just critical praise, but also Oscar talk, for her performance in the upcoming film Transamerica, in which she plays Sabrina "Bree" Osbourne, a pre- operative man-to-woman transsexual. After more than 20 years as an actress, this happily married, 42-year-old mother of two is today's "it" girl. "It couldn't happen to a nicer gal," says Housewives creator Marc Cherry. "Felicity is one of those success stories that was waiting to happen." Huffman has enjoyed the kindness of critics before, particularly for her role on Sports Night, an ABC sitcom in the late '90s. And Cherry points out that her stock in Hollywood has been high. "She has always had the respect of this entire industry," he says. But that's nothing like having a hit show and a movie with awards potential, albeit a modestly budgeted, art house-style film. -

Sultans and Voivodas in the 16Th C. Gifts and Insignia*

SULTANS AND VOIVODAS IN THE 16TH C. GIFTS AND INSIGNIA* Prof. Dr. Maria Pia PEDANI** Abstract The territorial extent of the Ottoman Empire did not allow the central government to control all the country in the same way. To understand the kind of relations established between the Ottoman Empire and its vassal states scholars took into consideration also peace treaties (sulhnâme) and how these agreements changed in the course of time. The most ancient documents were capitulations (ahdnâme) with mutual oaths, derived from the idea of truce (hudna), such as those made with sovereign countries which bordered on the Empire. Little by little they changed and became imperial decrees (berat), which mean that the sultan was the lord and the others subordinate powers. In the Middle Ages bilateral agreements were used to make peace with European countries too, but, since the end of the 16th c., sultans began to issue berats to grant commercial facilities to distant countries, such as France or England. This meant that, at that time, they felt themselves superior to other rulers. On the contrary, in the 18th and 19th centuries, European countries became stronger and they succeeded in compelling the Ottoman Empire to issue capitulations, in the form of berat, on their behalf. The article hence deals with the Ottoman’s imperial authority up on the vassal states due to the historical evidences of sovereignty. Key Words: Ottoman Empire, voivoda, gift, insignia. 1. Introduction The territorial extent of the Ottoman Empire did not allow the central government to control all the country in the same way. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

California Court Finds Wrongful Termination Tort Too Desperate, but Permits Statutory Claim for Disparate Treatment

Management Alert California Court Finds Wrongful Termination Tort Too Desperate, But Permits Statutory Claim For Disparate Treatment California employees can file tort claims against employers who impose adverse employment actions in violation of public policy. They have used this theory to challenge wrongful terminations and demotions. In Touchstone Television Productions v. Superior Court (Sheridan), the California Court of Appeal rejected an effort to extend this tort theory to an employer’s decision not to exercise an option to renew a contract. The Facts In 2004, Touchstone Television Productions (“Touchstone”) hired actress Nicollette Sheridan (“Sheridan”) to appear in a new television series, Desperate Housewives. The parties’ agreement gave Touchstone the option to annually renew Sheridan’s employment for up to six additional seasons. Touchstone exercised its option to renew the agreement with Sheridan for Seasons 2, 3, 4, and 5. During Season 5, Sheridan reported to Touchstone that Marc Cherry, the series’ creator, had hit her during the filming of an episode. Five months after this alleged incident, Touchstone informed Sheridan that it would not exercise its option to renew her contract for Season 6, because her character would be killed during Season 5. Sheridan continued to work during Season 5, filming three more episodes and doing publicity for the series. Sheridan sued Touchstone and Cherry in April 2010. She asserted various claims, including a claim that Touchstone fired her in retaliation for complaining about Cherry’s conduct. The Trial Court Decision The matter went to trial in February 2012. The jury deadlocked on the wrongful termination claim and the trial court declared a mistrial. -

Panoramic Trails to the Golden Cone Square Nature and Culture Between Altdorf, Burgthann and Postbauer-Heng S 2 Altdorf Dörlbach Schwarzenbach Buch Postbauer-Heng S 3

Panoramic trails to the golden cone square Nature and culture between Altdorf, Burgthann and Postbauer-Heng S 2 Altdorf Dörlbach Schwarzenbach Buch Postbauer-Heng S 3 73 Foreword Walking tour Dear visitors, 6 km from the -Bahn station (suburban railway station) Postbauer-Heng to the 1.5 hours -Bahn station Oberferrieden The joint decision of the environmental and building committees of both municipalities Postbauer-Heng Coming from the direction of Nuremberg you first walk (district of Neumarkt i. d. OPf.) and Burgthann (district through the pedestrian underpass to the other side of the of Nuremberg Land) on March 29, 2011 gave the go- railway line. From there via the ramp downwards and fur- ahead for this outstanding and “cross-border” project. ther on the foot and cycle path towards the main road B 8. The citizens of this region at the foot of the mountains Walk on through the tunnel tube and pass the skateboard Brentenberg and Dillberg have already been deeply root- tracks until you reach a crossroad in front of the sports ed for many generations. Numerous family and cultural club. Now turn right and go upwards. Until you reach connections were the basis for the increasingly growing Buch you will find the signs 1 2 along the way. As cooperation in economic and local affairs which has you turn left at the edge of the forest and walk on the proved to be a success especially concerning the school meadow path above of the sports club please enjoy the cooperation. The border between the municipalities is wide view over the surrounding area. -

Academic Catalog 2021-2022 ACADEMIC STANDARDS

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 5 PURPOSE .......................................................................................................................................... 5 MISSION ............................................................................................................................................. 5 VALUES .............................................................................................................................................. 5 INSTITUTIONAL VISION .................................................................................................................... 5 INSTITUTIONAL OBJECTIVES .......................................................................................................... 5 ACCREDITATION AND OPERATIONAL STATUS............................................................................. 5 COLLEGE COMMUNITY ................................................................................................................... 6 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................................................................................................. 6 OUR FACULTY ................................................................................................................................................ 6 OUR ALUMNI ......................................................................................................................... -

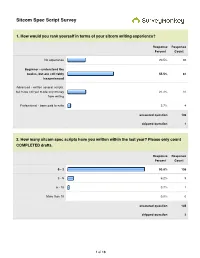

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

Act One Fade In: Int. Studio Backstage

30 ROCK 113: "The Head and The Hair" 1. Shooting Draft Third Revised (Yellow) 12/13/06 ACT ONE FADE IN: 1 INT. STUDIO BACKSTAGE - NIGHT 1 The show is in full swing. We hear a laugh from inside the studio, then applause and the band kicking in. The double doors burst open and JENNA, dressed as a fat old lady, LIZ, and a QUICK-CHANGE DRESSER enter the backstage chaos from the studio. In the background we see the STAGE MANAGER. STAGE MANAGER We’re back in two minutes! The dresser starts going to work on Jenna; tearing off a wig, casting aside props and jewelry. PETE is there. JENNA (to Liz) So are you gonna ask out the Head? Liz rolls her eyes. PETE The “Head”? LIZ There are these two MSNBC guys we keep seeing around. They just moved offices from New Jersey. We don’t know their names so we call them the Head and the Hair. PETE How come? FLASH BACK TO: 2 INT. ELEVATOR/ELEVATOR BANK - EARLIER THAT DAY 2 Liz and Jenna are on the elevator coming in to work. Two guys get on. One guy is super handsome and has great hair. This is THE HAIR, GRAY. The other guy is cranial and nerdy looking. This is THE HEAD. Liz smiles politely. Jenna gives the Hair a huge grin. GRAY Hey! You guys again. Jenna laughs too hard at this non-joke. 30 ROCK 113: "The Head and The Hair" 2. Shooting Draft Third Revised (Yellow) 12/13/06 JENNA How are things going? Are you settling in okay? GRAY We’re finding our way around. -

Idea Xxviii/2 2016

Rada Redakcyjna: Mira Czarnawska (Warszawa), Zbigniew Kaźmierczak (Białystok), Andrzej Kisielewski (Białystok), Jerzy Kopania (Białystok), Małgorzata Kowalska (Białystok), Dariusz Kubok (Katowice) Rada Naukowa: Adam Drozdek, PhD Associate Professor, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, USA Anna Grzegorczyk, prof. dr hab., UAM w Poznaniu Vladimír Leško, Prof. PhDr., Uniwersytet Pavla Jozefa Šafárika w Koszycach, Słowacja Marek Maciejczak, prof. dr hab., Wydział Administracji i Nauk Społecznych, Politechnika Warszawska David Ost, Joseph DiGangi Professor of Political Science, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, New York, USA Teresa Pękala, prof. dr hab., UMCS w Lublinie Tahir Uluç, PhD Associate Professor, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi Ilahiyat Fakultesi (Wydział Teologii), Konya, Turcja Recenzenci: Vladimír Leško, Prof. PhDr. Andrzej Niemczuk, dr hab. Andrzej Noras, prof. dr hab. Tahir Uluç, PhD Associate Professor Redakcja: dr hab. Sławomir Raube (redaktor naczelny) dr Agata Rozumko, mgr Karol Więch (sekretarze) dr hab. Dariusz Kulesza, prof. UwB (redaktor językowy) dr Kirk Palmer (redaktor językowy, native speaker) Korekta: Zespół Projekt okładki i strony tytułowej: Tomasz Czarnawski Redakcja techniczna: Ewa Frymus-Dąbrowska ADRES REDAKCJI: Uniwersytet w Białymstoku Plac Uniwersytecki 1 15-420 Białystok e-mail: [email protected] http://filologia.uwb.edu.pl/idea/idea.htm ISSN 0860–4487 © Copyright by Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, Białystok 2016 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku 15–097 Białystok, ul. Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie 14, tel. 857457120 http://wydawnictwo.uwb.edu.pl, e-mail: [email protected] Skład, druk i oprawa: Wydawnictwo PRYMAT, Mariusz Śliwowski, ul. Kolejowa 19, 15-701 Białystok, tel. 602 766 304, 881 766 304, e-mail: [email protected] SPIS TREŚCI WOJCIECH JÓZEF BURSZTA: Homo Barbarus w świecie algorytmów ................................................................................................. 5 ZBIGNIEW KAŹMIERCZAK: Demoniczność Boga jako założenie ekskluzywistycznego i inkluzywistycznego teizmu .................................. -

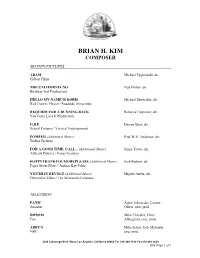

Brian H. Kim Composer

BRIAN H. KIM COMPOSER MOTION PICTURES ADAM Michael Uppendahl, dir. Gilbert Films THE CALIFORNIA NO Ned Ehrbar, dir. Birthday Suit Productions HELLO MY NAME IS DORIS Michael Showalter, dir. Red Crown / Haven / Roadside Attractions REQUIEM FOR A RUNNING BACK Rebecca Carpenter, dir. You Gotta Love It Productions G.B.F. Darren Stein, dir. School Pictures / Vertical Entertainment POMPEII (Additional Music) Paul W.S. Anderson, dir. TriStar Pictures FOR A GOOD TIME, CALL... (Additional Music) Jamie Travis, dir. AdScott Pictures / Focus Features HAPPYTHANKYOUMOREPLEASE (Additional Music) Josh Radnor, dir. Paper Street Films / Anchor Bay Films YOUTH IN REVOLT (Additional Music) Miguel Arteta, dir. Dimension Films / The Weinstein Company TELEVISION PANIC Adam Schroeder, Lauren Amazon Oliver, exec prod. BH90210 Mike Chessler, Chris Fox Alberghini, exec prod. ABBY’S Mike Schur, Josh Malmuth, NBC exec prod. 3349 Cahuenga Blvd. West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 Kim Page 1 of 3 BRIAN H. KIM COMPOSER TELEVISION (continued) GHOSTING: THE SPIRIT OF CHRISTMAS Lisa Kudrow, Dan Bucatinsky, Freeform exec prod. SEARCH PARTY Michael Showalter, exec prod. TBS STAR VS. THE FORCES OF EVIL Daron Nefcy, exec prod. Disney Television Animation / Disney XD SIGNIFICANT MOTHER Tripp Reed, Leslie Morgenstein, CW exec prod. DATING RULES FROM MY FUTURE SELF Bob Levy, Tripp Reed, exec Hulu prod. FRIENDS-IN-LAW (pilot) Brian Gallivan, exec prod. NBC / Warner Brothers MOST LIKELY TO (pilot) Greg Berlanti, Diablo Cody, Berlanti Productions / ABC exec prod. ADULT CONTENT (pilot) Topher Grace, Jenna Fischer, 20th Century Fox prod. GOOD FORTUNE (pilot) Kourtney Kang, Matt Zinman, NBC exec prod. -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

Re-Election Open to All Undergrads Former Candidates React with for Students

Undefeated women’s rugby team THE DAILY seeks funds sports Page 7 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 15, 2009 THE STUDENT VOICE EverOF WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1895 greenVol 115 No. 136 LOCAL WSU will offer an online MBA Re-election open to all undergrads Former candidates react with for students. and Hendrickson to re-run. « THERE WERE SO MANY Beginning this fall, the mixed feelings toward another “Jay and I have every intention “I find it completely unfair,” he WSU College of Business to run in the re-election,” he said. said. “They were found guilty of MISTAKES THE J-BOARD will launch a 39-credit decision from the Election Board. “A J-Board verdict will not stop us faulty campaigning, but they are MADE ALONG THE WAY THAT online MBA program. from running.” being allowed to run anyway. That The program will work TAKE AWAY FROM By Dan Warn Other former tickets aren’t as in partnership with WSU’s Evergreen staff is like telling a murderer, ‘You are THEIR CREDIBILITY.» Center for Distance and optimistic. guilty, now go back on the streets.’” Professional Education The Election Board changed its While Jake Bredstrand said En’Wezoh said there are multi- and is accredited by The mind about how the ASWSU re- he is still weighing his options, ple sides to the story, and support- Derick En’Wezoh Association to Advance election will run. Ryan Mulenga and Sarah Driscoll ers of every ticket violated bylaws. Student Regent Collegiate Schools of Instead of its original decision declined to participate in a re- It is possible that his ticket was for En’Wezoh and Hendrickson in Business.