California Court of Appeal Opinion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USA TODAY Life Section D Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Cover Story

USA TODAY Life Section D Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Cover Story: http://www.usatoday.com/life/people/2005-11-21-huffman_x.htm Felicity Huffman is sitting pretty: Emmy-winning Housewives star ignites Oscar talk for transsexual role By William Keck, USA TODAY By Dan MacMedan, USA TODAY Has it all: An actress for more than twenty years, Felicity Huffman has an Emmy for her role on hit Desperate Housewives, a critically lauded role in the film Transamerica, a famous husband (William H. Macy) and two daughters. 2 WEST HOLLYWOOD Felicity Huffman is on a wild ride. Her ABC show, Desperate Housewives, became hot, hot, hot last season and hasn't lost much steam. She won the Emmy in September over two of her Housewives co-stars. And now she is getting not just critical praise, but also Oscar talk, for her performance in the upcoming film Transamerica, in which she plays Sabrina "Bree" Osbourne, a pre- operative man-to-woman transsexual. After more than 20 years as an actress, this happily married, 42-year-old mother of two is today's "it" girl. "It couldn't happen to a nicer gal," says Housewives creator Marc Cherry. "Felicity is one of those success stories that was waiting to happen." Huffman has enjoyed the kindness of critics before, particularly for her role on Sports Night, an ABC sitcom in the late '90s. And Cherry points out that her stock in Hollywood has been high. "She has always had the respect of this entire industry," he says. But that's nothing like having a hit show and a movie with awards potential, albeit a modestly budgeted, art house-style film. -

California Court Finds Wrongful Termination Tort Too Desperate, but Permits Statutory Claim for Disparate Treatment

Management Alert California Court Finds Wrongful Termination Tort Too Desperate, But Permits Statutory Claim For Disparate Treatment California employees can file tort claims against employers who impose adverse employment actions in violation of public policy. They have used this theory to challenge wrongful terminations and demotions. In Touchstone Television Productions v. Superior Court (Sheridan), the California Court of Appeal rejected an effort to extend this tort theory to an employer’s decision not to exercise an option to renew a contract. The Facts In 2004, Touchstone Television Productions (“Touchstone”) hired actress Nicollette Sheridan (“Sheridan”) to appear in a new television series, Desperate Housewives. The parties’ agreement gave Touchstone the option to annually renew Sheridan’s employment for up to six additional seasons. Touchstone exercised its option to renew the agreement with Sheridan for Seasons 2, 3, 4, and 5. During Season 5, Sheridan reported to Touchstone that Marc Cherry, the series’ creator, had hit her during the filming of an episode. Five months after this alleged incident, Touchstone informed Sheridan that it would not exercise its option to renew her contract for Season 6, because her character would be killed during Season 5. Sheridan continued to work during Season 5, filming three more episodes and doing publicity for the series. Sheridan sued Touchstone and Cherry in April 2010. She asserted various claims, including a claim that Touchstone fired her in retaliation for complaining about Cherry’s conduct. The Trial Court Decision The matter went to trial in February 2012. The jury deadlocked on the wrongful termination claim and the trial court declared a mistrial. -

Academic Catalog 2021-2022 ACADEMIC STANDARDS

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 5 PURPOSE .......................................................................................................................................... 5 MISSION ............................................................................................................................................. 5 VALUES .............................................................................................................................................. 5 INSTITUTIONAL VISION .................................................................................................................... 5 INSTITUTIONAL OBJECTIVES .......................................................................................................... 5 ACCREDITATION AND OPERATIONAL STATUS............................................................................. 5 COLLEGE COMMUNITY ................................................................................................................... 6 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................................................................................................. 6 OUR FACULTY ................................................................................................................................................ 6 OUR ALUMNI ......................................................................................................................... -

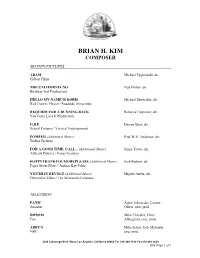

Brian H. Kim Composer

BRIAN H. KIM COMPOSER MOTION PICTURES ADAM Michael Uppendahl, dir. Gilbert Films THE CALIFORNIA NO Ned Ehrbar, dir. Birthday Suit Productions HELLO MY NAME IS DORIS Michael Showalter, dir. Red Crown / Haven / Roadside Attractions REQUIEM FOR A RUNNING BACK Rebecca Carpenter, dir. You Gotta Love It Productions G.B.F. Darren Stein, dir. School Pictures / Vertical Entertainment POMPEII (Additional Music) Paul W.S. Anderson, dir. TriStar Pictures FOR A GOOD TIME, CALL... (Additional Music) Jamie Travis, dir. AdScott Pictures / Focus Features HAPPYTHANKYOUMOREPLEASE (Additional Music) Josh Radnor, dir. Paper Street Films / Anchor Bay Films YOUTH IN REVOLT (Additional Music) Miguel Arteta, dir. Dimension Films / The Weinstein Company TELEVISION PANIC Adam Schroeder, Lauren Amazon Oliver, exec prod. BH90210 Mike Chessler, Chris Fox Alberghini, exec prod. ABBY’S Mike Schur, Josh Malmuth, NBC exec prod. 3349 Cahuenga Blvd. West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 Kim Page 1 of 3 BRIAN H. KIM COMPOSER TELEVISION (continued) GHOSTING: THE SPIRIT OF CHRISTMAS Lisa Kudrow, Dan Bucatinsky, Freeform exec prod. SEARCH PARTY Michael Showalter, exec prod. TBS STAR VS. THE FORCES OF EVIL Daron Nefcy, exec prod. Disney Television Animation / Disney XD SIGNIFICANT MOTHER Tripp Reed, Leslie Morgenstein, CW exec prod. DATING RULES FROM MY FUTURE SELF Bob Levy, Tripp Reed, exec Hulu prod. FRIENDS-IN-LAW (pilot) Brian Gallivan, exec prod. NBC / Warner Brothers MOST LIKELY TO (pilot) Greg Berlanti, Diablo Cody, Berlanti Productions / ABC exec prod. ADULT CONTENT (pilot) Topher Grace, Jenna Fischer, 20th Century Fox prod. GOOD FORTUNE (pilot) Kourtney Kang, Matt Zinman, NBC exec prod. -

CATHERINE ADAIR Costume Designer Catherineadair.Com

CATHERINE ADAIR Costume Designer catherineadair.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS PERRY MASON Deniz Gamze Erguven HBO Season 2 Regina Heyman, Jack Amiel Michael Begler THE MYSTERIOUS BENEDICT SOCIETY James Bobin 20TH CENTURY FOX / DISNEY+ Pilot & Series Various Directors Grace Gilroy, Todd Slavkin Darren Swimmer THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE Ernest R. Dickerson SCOTT FREE / AMAZON Seasons 3 - 4 Daniel Percival Richard Heus, Eric Overmyer Nomination, Best Costume Design– Alex Zakrewski Dan Percival, David Scarpa CDG Awards Various Directors FATE: THE WINX CLUB SAGA Stephen Woolfenden ARCHERY PICTURES / NETFLIX Season 1 Hannah Quinn Jon Finn Lisa James Larsen THE SON Tom Harper SONAR ENTERTAINMENT / AMC Pilot & Season 1 Kevin Dowling Kevin Dowling, Kevin Murphy Various Directors Jenna Glazier BOSCH Kevin Dowling AMAZON / Pieter Jan Brugge Seasons 1 - 2 Various Directors Eric Overmyer, Henrik Bastin RAKE Sam Rami SONY TV / FOX Series Cherie Nowlan George Perkins, Peter Tolan Various Directors Sam Raimi, Michael Wimer HALLELUJAH Pilot Michael Apted ABC / Marc Cherry, Sabrina Wind DESPERATE HOUSEWIVES 8 Seasons Larry Shaw ABC Nominations (4), Best Costume Design– David Grossman George Perkins, Marc Cherry Emmy Awards Various Directors Michael Edelstein / Bob Daily Nominations (3), Best Costume Design– CDG Awards THE DISTRICT Terry George CBS / Denise Di Novi, John Wirth Pilot & Seasons 1 - 4 Various Directors Pam Veasey, Jim Chory Cleve Landsberg WIN A DATE WITH TAD HAMILTON! Robert Luketic DREAMWORKS SKG / Doug Wick Feature Film Lucy Fishe, William Beasley THE ‘70s Mini-Series Peter Werner NBC / Denise Di Novi, Jim Chory BASEketball Feature Film David Zucker UNIVERSAL / Gil Netter, David Zucker I KNOW WHAT YOU DID LAST Jim Gillespie COLUMBIA SUMMER Feature Film Neal Moritz, William Beasley BEVERLY HILLS COP III John Landis PARAMOUNT Feature Film Leslie Belzberg, Bob Rehme Ms. -

No Wrongful Termination Claim for Nonrenewal of Contract, but Retaliation Claim Allowed Under California Law by Mark S

Publications No Wrongful Termination Claim for Nonrenewal of Contract, But Retaliation Claim Allowed under California Law By Mark S. Askanas August 31, 2012 Meet the Author Desperate Housewives actress, Nicollette Sheridan, cannot pursue a claim for wrongful termination based on the television production company’s failure to renew her contract for an additional season, the California Court of Appeal has ruled. Touchstone Television Productions v. Superior Court (Sheridan), No. B241137 (Cal. Ct. App. Aug. 16, 2012). Although Sheridan contended that the production company fired her in violation of state public policy because she Mark S. Askanas complained about a battery committed upon her by the series’ creator, the Court Principal declined to fashion a new tort for nonrenewal of a fixed-term employment San Francisco 415-394-9400 contract and directed the trial court to enter a verdict in favor of the production Email company. However, the Court would permit Sheridan to amend her complaint to assert a claim for retaliation for complaints about unsafe working conditions under Section 6310(b) of the California Labor Code. Practices Litigation Background Touchstone Television Productions hired Sheridan for the television series Desperate Housewives, pursuant to an employment agreement. The agreement was for the initial season, but it gave Touchstone the exclusive option to renew the agreement for up to an additional six seasons. Touchstone renewed its agreement with Sheridan for Seasons 2 through 5. During the filming of Season 5, Sheridan alleged that the series creator, Marc Cherry, hit her. Sheridan complained to Touchstone about the alleged battery. Thereafter, Touchstone informed Sheridan it would not renew her agreement for Season 6 and that her character would be killed in a car accident. -

TLC Press Highlights EXTREME COUGAR WIVES December 2013 & January 2014 MY CRAZY OBSESSION

BREAKING aMiSH l.a. DeVIOUS MAIDS SERIES FINALE TLC Press Highlights eXTREMe COUGAR WIVeS December 2013 & January 2014 My CRAZy oBSeSSION Sky 125 I Virgin 167 I BT TV 875 I youView on TalkTalk PLAYER eXTREMe BEAUTy DiSaSTERS HONEY BOO BOO BREAKING AMISH L.A. uk SerieS PreMiere January, 2014 Following the original success of Breaking Amish, TLC UK’s highest rating new series of 2013, Breaking Amish: Los Angeles takes a new group of young Amish and Mennonite adults, as they trade in their old world traditions, this time for the modern temptations and glamour of LA. Will they embrace this new world and the freedom that they’ve always dreamed of, or yearn for the simpler life they left behind? DEVIOUS MAIDS uk SerieS PreMiere - SerieS Finale wednesday 1st January, 10.00pm From Marc Cherry, the creator of Desperate Housewives, and executive producer Eva Longoria, Devious Maids came to TLC this October following its huge success in the US - already commissioned for a second series. The 13-part drama centres on a close-knit group of maids working in the homes of Beverly Hills’ wealthiest and most powerful families. The women come together to uncover the truth when their friend and fellow maid is murdered at the home of her employers. Starring Ana Ortiz (Ugly Betty), Roselyn Sánchez (Rush Hour 2), Dania Ramirez (X-Men: The Last Stand), Judy Reyes (Scrubs) and Susan Lucci (All My Children). In this series finale, Taylor learns she has lost the baby, and tells Michael it’s time to tell Marisol the truth. -

REPRESENTATION of LATINAS1 AS MAIDS on DEVIOUS MAIDS (2013) Fitria Afrianty Sudirman

42 Paradigma, Jurnal Kajian Budaya Representation of Latinas as Maids on Devious Maids, Fitria Afrianty Sudirman 43 REPRESENTATION OF LATINAS1 AS MAIDS ON DEVIOUS MAIDS (2013) Fitria Afrianty Sudirman Abstract This article aims to analyze the representation of Latinas as maids by examining the first season of US television drama comedy, Devious Maids. The show has been a controversy inside and outside Latina community since it presents the lives of five Latinas working as maids in Beverly Hills that appears to reinforce the negative stereotypes of Latinas. However, a close reading on scenes by using character analysis on two Latina characters shows that the characters break stereotypes in various ways. The show gives visibility to the Latinas by putting them as main characters and portraying them as progressive and independent women who also refuse the notion of white supremacy. Keywords Latina, stereotypes, television, Devious Maids. INTRODUCTION Latin Americans have grown to be the largest minority group in the United States (US). According to the 2010 US Census, those identifying themselves as Hispanic/Latino Americans increased by 43% from the 2000 US Census, comprising 16% of the U.S total population. The bureau even expected that by 2050, the Hispanic/Latino population in the U.S. will be 132.8 million or 30% of the total population, which means one out of three Americans is a Hispanic/Latino. However, the increasing number of Latin Americans does not seem to go along with the portrayal of them in the US television. Research shows that they remain significantly under-represented on TV, only 1%-3% of the primetime TV population (Mastro-Morawitz, 2005). -

Hell Hath No Fury Like a Woman Scorned. Why Women Kill Premieres on 10 All Access

Media Release 8 August 2019 Hell Hath No Fury Like A Woman Scorned. Why Women Kill Premieres On 10 All Access. Looking for your next favourite 10 All Access series? Then look no further as the original dark comedy-drama series Why Women Kill is launching Friday, 16 August. Available to view at the same time as the United States, the new weekly Network 10 series from Desperate Housewives creator Marc Cherry, stars Lucy Liu, Ginnifer Goodwin and Kirby Howell-Baptiste. A CBS Company Why Women Kill follows the lives of three women living in three different decades: a housewife in the 1960s, a socialite in the 1980s and a lawyer in 2019, each dealing with infidelity in their marriages. The deliciously dark series will examine how the roles of women have changed over the decades, but how their reaction to betrayal…has not. Playing 1960s housewife Beth Ann Stanton is Ginnifer Goodwin. Best known for her roles in HBO’s Big Love and ABC’s Once Upon a Time, Ginnifer can be seen in 10 All Access’ The Twilight Zone. Her film credits include the animated film Zootopia, Walk the Line, Killing Kennedy, Mona Lisa Smile, Win a Date with Tad Hamilton, Something Borrowed and He’s Just Not That Into You. Starring as 1980s socialite Simone Grove is critically-acclaimed actress Lucy Liu. For six seasons, Lucy has co-starred in Network 10’s highly praised drama Elementary as Dr. Joan Watson, alongside Jonny Lee Miller as Sherlock Holmes. Lucy’s other television credits include Southland, Ally McBeal, Cashmere Mafia, Dirty Sexy Money and guest-starring roles in Sex and the City and Ugly Betty. -

Stephanie's Resume

STEPHANIE GORIN CASTING DIRECTOR CSA/C.D.C 2014 EMMY WINNER, BEST CASTING for a MINI-SERIES 2014 ARTIOS WINNER, BEST CASTING for a MINI-SERIES 3 EMMY NOMINATIONS 3 GEMINI NOMINATIONS 4 ARTIOS AWARD NOMINATIONS 62 Ellerbeck St., Toronto ON Canada M4K 2V1 PH: 416-778-6916 Email: [email protected] FEATURE FILMS, MOVIES OF THE WEEK, EPISODICS (selected) ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW T.V. Feature 2016 Director: Kenny Ortega Executive Producers: Lou Adler, Gail Berman, Kenny Ortega / FOX 21 TELEVISION STUDIOS RACE – Co-Casting Feature 2015 Director: Stephen Hopkins Producers: Jean-Charles Levy, Luc Seguin, Karsten Brunig, Nicolas Manuel / Focus Features/Forecast Pictures FARGO (Seasons 1-2) Mini-Series 2014-2015 Director: Various Executive Producers: Joel & Ethan Coen, Noah Hawley, Warren Littlefield & John Cameron, Geyer Kosinski / MGM / FX *Emmy winner for casting – 2014 *Artios winner – 2014 HEROES REBORN T.V. Series 2015 Directors: Various Executive Producers: Tim Kring, Peter Elkoff, James Middleton / NBC OPERATION INSANITY Feature 2015 Director: Erik Canuel Executive Producer: Arnie Zipursky, CCI Entertainment SHADOWHUNTERS T.V. Series 2015 Director: Various Executive Producers: McG, Marjorie David, Ed Decter, Michael Reisz, Don Carmody / ABC Family-FREEFORM PRIVATE EYES T.V. Series 2015 Director: Kelly Makin, Anne Wheeler Executive Producers: John Morayniss, Tecca Crosby, Rachel Fulford, Shawn Piller, Lloyd Segan, Jason Priestley Tassie Cameron, Shelley Eriksen, Alan McCullough THE PATRIOT Pilot 2015 Director: Steve Conrad Executive Producers: Charlie Gogolak, Glenn Ficarra, Dominic Garcia, Gil Bellows / AMAZON SLASHER Mini-Series 2015 Director: Craig David Wallace Executive Producers: Christina Jennings, Aaron Martin, Adam Haight / Chiller / SUPERCHANNEL CHEERLEADER DEATH SQUAD Pilot 2015 Director: Mark Waters Executive Producers: Marc Cherry, Neal Baer, Daniel Truly, Frank Siracusa, John Weber / CW / CBS SHOOT THE MESSENGER Series 2015 Directors: Sudz Sutherland, T.W. -

Yucaipa Performing Arts Center (YPAC) Presents

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Feb. 18, 2020 Yucaipa Performing Arts Center (YPAC) Presents Date Night Comedy Series – Featuring Barry Neal and Debbie Praver Thursday, Mar 19, 7PM | YPAC Indoor Theater Student / Senior / Military: $10 | General Admission: $20 | Groups of 10+: $15 12062 California St. Yucaipa, CA 92399 | 909.500.7714 | www.yucaipaperformingarts.org The Yucaipa Performing Arts Center (YPAC) is excited to present Barry Neal and Debbie Praver, two new Hollywood-based comedians in our Date Night Comedy Series. Neal and Praver will perform their act, “Love and Laughter,” with Ace Guillen hosting on March 19 at 7PM. Barry Neal’s clean, high-energy style has quickly moved him up the comedy ladder as a notable headliner. He’s made appearances on MTV, NBC, Comedy Central, and VH-1. His “Counselor of Love” act is currently being shopped as a sitcom, which Barry wrote along with Dan Patterson, the creator and executive producer of Whose Line Is It Anyway? Debbie Praver was a guest performer at the Las Vegas Comedy Festival, shared the stage with Kathy Griffin in Dennis Hensley's “Screening Party” and performs regularly at The Improv, The Comedy Store, and Friars Club. Debbie honed her writing skills with Desperate Housewives Creator, Marc Cherry, and Desperate Housewives Co-executive Producers, Joey Murphy and John Pardee. Two new Hollywood comedians will be performing at the YPAC every third Thursday of the month through May 2020. FREE child care is provided for one child (ages 4 – 13) per ticket purchased. To purchase tickets, go to www.yucaipaperformingarts.org, call the box office at 909.500.7714 or visit 12062 California Street, Yucaipa, CA. -

Gender Stereotypes in Desperate Housewives

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Martina Matijević Gender Stereotypes in Desperate Housewives Završni rad Zadar, 2018. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Gender Stereotypes in Desperate Housewives Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Martina Matijević Dr. sc. Zlatko Bukač Zadar,2018. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Martina Matijević, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Gender Stereotyes in Desperate Housewives rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 26. rujan 2018. Table of contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 2 Desperate Housewives ........................................................................................................ 2 3 Representation