A Critique of the Labeling Approach: Toward a Social Theory of Deviance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Children of Organized Crime Offenders: Like Father, Like Child?

Eur J Crim Policy Res https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-018-9381-6 Children of Organized Crime Offenders: Like Father, Like Child? An Explorative and Qualitative Study Into Mechanisms of Intergenerational (Dis)Continuity in Organized Crime Families Meintje van Dijk1 & Edward Kleemans1 & Veroni Eichelsheim 2 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract This qualitative descriptive study aims to explore (1) the extent of intergenerational continuity of crime in families of organized crime offenders, (2) the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon and (3) the mechanisms underlying intergenerational discontinuity. The study comprised a descriptive analysis of the available numeric information on 25 organized crime offenders based in Amsterdam and their 48 children of at least 19 years of age and a more qualitative in-depth analysis of police files, justice department files and child protection service files of all the family members of 14 of the 25 families. Additionally, interviews with employees of the involved organizations were conducted. In terms of prevalence in official record crime statistics, the results show that a large majority of the organized crime offenders’ sons seem to follow in their fathers’ footsteps. This is not the case for daughters, as half of them have a criminal record, but primarily for only one minor crime. Intergenerational transmission seems to be facilitated by mediating risk factors, inadequate parenting skills of the mother, the Bfamous^ or violent reputation of the father, and deviant social learning. If we want to break the intergenerational chain of crime and violence, the results seem to suggest that an accumulation of protective factors seem to be effective, particularly for girls. -

Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2011 Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory Rahim Manji [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, and the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Manji, Rahim, "Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/897 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Rahim Manji entitled "Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Sociology. Lois Presser, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Ben Feldmeyer Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory A Thesis Presented for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Tennessee, Knoxville Rahim Manji May, 2011 To the idea of a world in which injustice causes people to roil. -

Article Title Labeling Theory Anomie Theory Gun Spree at Columbine High

Article Title Labeling Theory Anomie Theory "Urgent need for concerted action by Congress, Gun Spree at Columbine High "trench coat mafia" state legislators, and gun manufacturers..." "Jocks, brains, burnouts, and goths, the black-clad Though Far from Colorado, One High "Now you have to worry even more, who you demimonde to which Mr. school is Feeling a Sense of the Terror can and can't be friends with" Harris and Mr. Dylan apparently belonged." "trench coat mafia" Letter to the Editor 3-No title "potential troublemakers" "I saw fire alarms had gone off, kids exiting the building, teachers helping kids A Principal's Grief out of the building" "Why were the 15 killed? Why? Life is so unfair." "the incident set off a national bout of soul "members of a self-styled searching and debates over...guns or by the group of loners and outcasts" violent images on television and in video games" "I can't even imagine walking into that school "trench coat mafia" right now...I don't think I ever want to set foot 2 Are Suspects; Delay Caused in there again" By Explosives "many parents say they moved to enroll their "popular students whom they students in good and safe public schools, grief referred to as jocks" and shock were pervasive" "largest school massacre by students in the country's "repercussions were felt far beyond Colorado" history" "two troubled, suicidal killers" "School Security"; "Early Intervention"; The Scourge of School Violence "Gun Control" "troubled students" "trench coat mafia" "trench-coat-clad student" Authorities Find a Large -

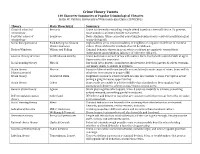

Crime Theory Tweets 140 Character Summaries of Popular Criminological Theories Justin W

Crime Theory Tweets 140 Character Summaries of Popular Criminological Theories Justin W. Patchin, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire (CRMJ 301) Theory Main Theorist(s) Summary Classical school of Beccaria Crime is inherently rewarding. People offend based on a free will choice. To prevent, criminology must punish so potential benefit not worth it. Positivist school of Lombroso Born criminals. Crime caused by something beyond person’s control (usually biological criminology or psychological). Social disorganization Park & Burgess; Shaw & High mobility areas result in inability of neighbors to organize in defense of common McKay; Sampson values. Physical disorder symbols of social breakdown. Broken Windows Wilson and Kelling Criminal behavior thrives in areas where residents are apathetic toward their environment and neighbors (absence of collective efficacy). General theory of crime Gottfredson & Hirschi Crime & deviance a result of low self-control. One’s level of self-control stabile at age 8. Opportunity also important. Social bonding theory Hirschi Our bond (attachment, commitment, involvement, belief) to parents & others restrains our innate desire to engage in deviance. Strain theory Merton Pursuit of American Dream (wealth accumulation) is main cause of crime. Some will do (classic/anomie) whatever is necessary to acquire $$$. Strain theory Cloward & Ohlin Illegitimate means to achieve wealth are also inaccessible to some. Perception is that joining a gang increases opportunities. Strain theory Cohen Some youth are unable to achieve middle-class standards so they supplant legit pursuits with desire to achieve status/respect among peers. General strain theory Agnew Strain plus negative affect equals crime. 3 sources: inability to achieve; something valued removed; something painful introduced. -

Social Disorganization Theory: the Role of Diversity in New Jersey's Hate Crimes Dana Maria Ciobanu Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2016 Social Disorganization Theory: The Role of Diversity in New Jersey's Hate Crimes Dana Maria Ciobanu Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Dana Ciobanu has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Patricia Ripoll, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Gema Hernandez, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Matthew Jones, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2016 Abstract Social Disorganization Theory: The Role of Diversity in New Jersey’s Hate Crimes by Dana Maria Ciobanu MPA, Seton Hall University, 2005 MADIR, Seton Hall University, 2005 BA, Seton Hall University, 2000 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University August 2016 Abstract The reported number of hate crimes in New Jersey continues to remain high despite the enforcement of laws against perpetrators. -

Labeling Theory: the New Perspective

The Corinthian Volume 2 Article 1 2000 Labeling Theory: The New Perspective Doug Gay Georgia College & State University Follow this and additional works at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian Part of the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Gay, Doug (2000) "Labeling Theory: The New Perspective," The Corinthian: Vol. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Knowledge Box. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Corinthian by an authorized editor of Knowledge Box. Labeling Theory: The New Perspective Doug Gay Faculty Sponsor: Terry Wells Abstract This report describes and examines the writings of crimi nologists from the labeling perspective and focuses on why and how some people come to be defined as deviant and what happens when they are so defined. This paper also addresses the develop ment of labeling theory and the process an individual undergoes to become labeled as deviant. Also examined is the relationship of labeling theory to empirical testing, the value of the theory, and implications for further research. Introduction All social groups make rules and attempt, at some times and under some circumstances, to enforce them. Social rules define sit uations and the kinds of behavior appropriate to them, specifying some actions as right and forbidding others as wrong. When a rule is enforced, the person who is supposed to have broken it may be seen as a special kind of person, one who cannot be trusted to live by the rules agreed upon by the group. -

Readings for Graduate Criminology Comprehensive Exam

READINGS FOR GRADUATE CRIMINOLOGY COMPREHENSIVE EXAM The following subdivisions are simply meant to be a heuristic device. They are not necessarily mutually exclusive or exhaustive. Note: Students are responsible for the last 5 years of articles in scholarly journals related to the area including Criminology, Criminology and Public Policy, and related papers published in the American Sociological Review, the American Journal of Sociology, and Social Forces and all other top journals. Social Disorganization and the Chicago School Bursik, R.J. 1988. "Social Disorganization theories of crime and delinquency: Problems and Prospects." Criminology 26:519-552. Morenoff, J., R. Sampson and S. Raudenbush. 2001. “Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence.” Criminology 39 (3): 517-559. Park, Robert E. 1915. “The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behavior in the City Environment. American Journal of Sociology 20: 577-612. Rose, D. and T. Clear. 1998. "Incarceration, social capital and crime: implications for social disorganization theory." Criminology 36:441-479. Sampson, R. 2012. The Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. University of Chicago Press. Sampson, R., S.W. Raudenbush and F. Earls. 1997."Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy." Science 277: 918-924. Sampson, R., and Groves, W.B. (1989). “Community Structure and Crime: Testing Social- Disorganization Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 94 (4): 774-802. Shaw, Clifford R., and Henry D. McKay. 1942. Juvenile Delinquency in Urban Areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Differential Association and Social Learning Theories Akers, R. L. 1998. Social Learning and Social Structure: A General Theory of Crime and Deviance. -

Labeling Effects of First Juvenile Arrests

LABELING EFFECTS OF FIRST JUVENILE ARRESTS: SECONDARY DEVIANCE AND SECONDARY SANCTIONING* Akiva M. Liberman Justice Policy Center, Urban Institute David S. Kirk University of Texas at Austin KiDeuk Kim Justice Policy Center, Urban Institute Feb 2014 Manuscript. In press, Criminology * This research was funded by the grant 2010-MU-FX-0613 from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the U.S. Department of Justice. We are grateful to the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods for providing the data necessary to undertake this study. First Juvenile Arrests 1 Labeling Effects of First Juvenile Arrests: Secondary Deviance and Secondary Sanctioning ABSTRACT A growing literature suggests that juvenile arrests perpetuate offending and increase the likelihood of future arrests. The effect on subsequent arrests is generally regarded to be a product of the perpetuation of criminal offending. However, increased rearrest may also reflect differential law enforcement behavior. Using longitudinal data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) together with official arrest records, the current study estimates the effects of first arrests on both reoffending and rearrest. Propensity score methods were used to control differences between arrestees and non-arrestees and minimize selection bias. Among 1,249 PHDCN youth, 58 were first arrested during the study period; 43 of these arrestees were successfully matched to 126 control cases who were equivalent on a broad set of individual, family, peer, and neighborhood factors. -

Criminal Justice System Involvement and Continuity of Youth Crime: a Longitudinal Test of Labeling Theory Lee Michael Johnson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2001 Criminal justice system involvement and continuity of youth crime: a longitudinal test of labeling theory Lee Michael Johnson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Criminology Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lee Michael, "Criminal justice system involvement and continuity of youth crime: a longitudinal test of labeling theory " (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1051. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1051 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fiims the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

ASSESSING the INNOCENCE and VICTIMIZATION of CHILD SOLDIERS by KATHRYN ELIZABETH BRONS ADAM LANKFORD, COMMITTEE CHAIR MARK LANI

ASSESSING THE INNOCENCE AND VICTIMIZATION OF CHILD SOLDIERS by KATHRYN ELIZABETH BRONS ADAM LANKFORD, COMMITTEE CHAIR MARK LANIER KARL DEROUEN JR. A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Criminal Justice in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2013 Copyright Kathryn Elizabeth Brons 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT To date, the majority stance taken by researchers in the field of criminology has been that child soldiers should be treated as innocent victims of war. While there have been some authors who have examined whether this label should be attached to the child, none have firmly taken the minority side in this debate. International law disregards the criminal acts against humanity committed by a child soldier and instead criminalizes the adults who either abducted the child for military duty or allowed the child to willingly volunteer for the armed services. This thesis proposes that many child soldiers are not innocent victims, but they are instead perpetrators of violence. In doing so, definitions of ‘innocent’ and ‘victim’ are called upon to show how many child soldiers are neither of these things and are able to take advantage of the International Criminal Court because of the ambiguity in international law. Labeling theory is used as the theoretical framework for this thesis. By labeling child soldiers as innocent victims, it has an adverse effect that allows child soldiers to continue committing criminal acts. ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my loving husband and supportive family. You drive me to always think outside the box. -

The Impact of Labeling in Childhood on the Sense of Self of Young Adults Rosemary Solomon, BA Department of Child & Youth St

The Impact of Labeling in Childhood on the Sense of Self of Young Adults Rosemary Solomon, BA Department of Child & Youth Studies Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Social Sciences, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario ©2015 Abstract Research studies on labeling of children have either focused on the effects of formal labels on the lives of children with exceptionalities and mental health issues, or the effect of informal labeling by parents, peers and teachers on teenagers. The effects of informal labeling in childhood and its implications in later life or for one’s career choice have not yet been examined. This study adds to the growing research on informal labeling. The purpose of this qualitative study was to determine what negative effects informal labeling of children as deviant had on their lives. Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews conducted with seventeen young adults, between the ages of sixteen and thirty years, from a post-secondary institution and an organization for homeless youth. The results showed an initial negative impact on the lives of the young adults during their childhood and early teenage years but as they progressed into their late teens and early adulthood, most were able to overcome their negative labels suggesting resilience. There were no significant gender differences in the impact of the labels. The implications of the study for policy makers and parents are discussed as well as some recommendations for parents and practitioners are offered. Key words: informal labeling, sense of self, deviance, young adults, childhood i Acknowledgement My deepest gratitude goes to God Almighty for His guidance and successful completion of this thesis.