Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Vikings History

FAITH AND FAMILY ARE TESTED AS THE STRUGGLE OVER POWER, LAND & LOYALTY RAID ON… VIKINGS HISTORY®’s Hit Drama Series Sets Sail for Season Three Thursday, February 19 at 10 pm ET/PT Canadians Lothaire Bluteau and Kevin Durand Join the Cast For additional photography and press kit material visit: http://www.shawmedia.ca/Media and follow us on Twitter at @shawmediaTV_PR For Immediate Release NEW YORK/TORONTO, December 16, 2014 – Season three of HISTORY’s hit scripted drama series Vikings returns on Thursday, February 19 at 10 pm ET/PT. In the new 10-episode season, Ragnar (Travis Fimmel), the former farmer, is now King and has great responsibility resting on his shoulders. With the promise of new land from the English, Ragnar leads his people to an uncertain fate on the shores of Wessex. King Ecbert (Linus Roache) has made many promises and it remains to be seen if he will keep them. This season, the ever-ambitious Ragnar searches for something more – and he finds it in the mythical city of Paris. Rumoured to be impenetrable to outside forces, Ragnar and his band of Norsemen must come together to break down its walls and cement the Vikings legend in history. The gripping family saga of Ragnar, Rollo (Clive Standen), Lagertha (Canadian Katheryn Winnick) and Bjorn (Canadian Alexander Ludwig) continues as alliances and loyal friendships are questioned, faith is catechized and relationships are strained. Vikings tells the extraordinary tales of the lives and epic adventures of these warriors and portrays life in the Dark Ages, a world ruled by raiders and explorers, through the eyes of Viking society. -

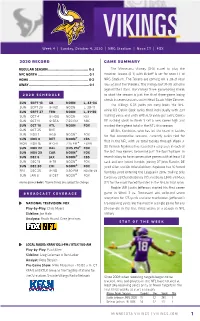

VIKINGS 2020 Vikings

VIKINGS 2020 vikings Week 4 | Sunday, October 4, 2020 | NRG Stadium | Noon CT | FOX 2020 record game summary REGULAR SEASON......................................... 0-3 The Minnesota Vikings (0-3) travel to play the NFC NORTH ....................................................0-1 Houston Texans (0-3) with kickoff is set for noon CT at HOME ............................................................ 0-2 NRG Stadium. The Texans are coming off a 28-21 road AWAY .............................................................0-1 loss against the Steelers. The Vikings lost 31-30 at home against the Titans. The Vikings three-game losing streak 2020 schedule to start the season is just the third three-game losing streak in seven seasons under Head Coach Mike Zimmer. sun sept 13 gb noon l, 43-34 The Vikings 6.03 yards per carry leads the NFL, sun sept 20 @ ind noon l, 28-11 sun sept 27 ten noon l, 31-30 while RB Dalvin Cook ranks third individually with 294 sun oct 4 @ hou noon fox rushing yards and sixth with 6.13 yards per carry. Cook’s sun oct 11 @ sea 7:20 pm nbc 181 rushing yards in Week 3 set a new career high and sun oct 18 atl noon fox marked the highest total in the NFL this season. sun oct 25 bye LB Eric Kendricks, who has led the team in tackles sun nov 1 @gb noon* fox for five consecutive seasons, currently ranks tied for sun nov 8 det noon* cbs first in the NFL with 33 total tackles through Week 3. mon nov 16 @ chi 7:15 pm* espn sun nov 22 dal 3:25 pm* fox DE Yannick Ngakoue has recorded a strip sack in each of sun nov 29 car noon* fox the last two games, becoming just the fourth player in sun dec 6 jax noon* cbs team history to have consecutive games with at least 1.0 sun dec 13 @ tb noon* fox sack and one forced fumble, joining DT John Randle, DE sun dec 20 chi noon* fox Jared Allen and DE Brian Robison. -

History Channel's Fact Or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion Gypsey Teague Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 10-31-2015 The iV kings: History Channel's Fact or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion Gypsey Teague Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Teague, Gypsey, "The iV kings: History Channel's Fact or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion" (2015). Presentations. 60. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/60 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Vikings: History Channel’s Fact or Fictionalized View of The Norse Expansion Presented October 31, 2015 at the New England Popular Culture Association, Colby-Sawyer College, New London, NH ABSTRACT: The History Channel’s The Vikings is a fictionalized history of Ragnar Lothbrok who during the 8th and 9th Century traveled and raided the British Isles and all the way to Paris. This paper will look at the factual Ragnar and the fictionalized character as presented to the general viewing public. Ragnar Lothbrok is getting a lot of air time recently. He and the other characters from the History Channel series The Vikings are on Tee shirts, posters, books, and websites. The jewelry from the series is selling quickly on the web and the actors that portray the characters are in high demand at conventions and other venues. The series is fun but as all historic series creates a history that is not necessarily accurate. -

Saturday Church

SATURDAY CHURCH A Film by Damon Cardasis Starring: Luka Kain, Margot Bingham, Regina Taylor, Marquis Rodriguez, MJ Rodriguez, Indya Moore, Alexia Garcia, Kate Bornstein, and Jaylin Fletcher Running Time: 82 minutes| U.S. Narrative Competition Theatrical/Digital Release: January 12, 2018 Publicist: Brigade PR Adam Kersh / [email protected] Rob Scheer / [email protected] / 516-680-3755 Shipra Gupta / [email protected] / 315-430-3971 Samuel Goldwyn Films Ryan Boring / [email protected] / 310-860-3113 SYNOPSIS: Saturday Church tells the story of 14-year-old Ulysses, who finds himself simultaneously coping with the loss of his father and adjusting to his new responsibilities as man of the house alongside his mother, younger brother, and conservative aunt. While growing into his new role, the shy and effeminate Ulysses is also dealing with questions about his gender identity. He finds an escape by creating a world of fantasy for himself, filled with glimpses of beauty, dance and music. Ulysses’ journey takes a turn when he encounters a vibrant transgender community, who take him to “Saturday Church,’ a program for LGBTQ youth. For weeks Ulysses manages to keep his two worlds apart; appeasing his Aunt’s desire to see him involved in her Church, while spending time with his new friends, finding out who he truly is and discovering his passion for the NYC ball scene and voguing. When maintaining a double life grows more difficult, Ulysses must find the courage to reveal what he has learned about himself while his fantasies begin to merge with his reality. *** DAMON CARDASIS, DIRECTOR STATEMENT My mother is an Episcopal Priest in The Bronx. -

Editors' Introduction Douglas A

Editors' Introduction Douglas A. Anderson Michael D. C. Drout Verlyn Flieger Tolkien Studies, Volume 7, 2010 Published by West Virginia University Press Editors’ Introduction This is the seventh issue of Tolkien Studies, the first refereed journal solely devoted to the scholarly study of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. As editors, our goal is to publish excellent scholarship on Tolkien as well as to gather useful research information, reviews, notes, documents, and bibliographical material. In this issue we are especially pleased to publish Tolkien’s early fiction “The Story of Kullervo” and the two existing drafts of his talk on the Kalevala, transcribed and edited with notes and commentary by Verlyn Flieger. With this exception, all articles have been subject to anonymous, ex- ternal review as well as receiving a positive judgment by the Editors. In the cases of articles by individuals associated with the journal in any way, each article had to receive at least two positive evaluations from two different outside reviewers. Reviewer comments were anonymously conveyed to the authors of the articles. The Editors agreed to be bound by the recommendations of the outside referees. The Editors also wish to call attention to the Cumulative Index to vol- umes one through five of Tolkien Studies, compiled by Jason Rea, Michael D.C. Drout, Tara L. McGoldrick, and Lauren Provost, with Maryellen Groot and Julia Rende. The Cumulative Index is currently available only through the online subscription database Project Muse. Douglas A. Anderson Michael D. C. Drout Verlyn Flieger v Abbreviations B&C Beowulf and the Critics. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

On the Origins of the Gothic Novel: from Old Norse to Otranto

This extract is taken from the author's original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: https:// www.palgrave.com/gb/book/9781137465030 and https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/9781137465047. Please be aware that if third party material (e.g. extracts, figures, tables from other sources) forms part of the material you wish to archive you will need additional clearance from the appropriate rights holders. On the origins of the Gothic novel: From Old Norse to Otranto Martin Arnold A primary vehicle for the literary Gothic in the late eighteenth to early nineteen centuries was past superstition. The extent to which Old Norse tradition provided the basis for a subspecies of literary horror has been passed over in an expanding critical literature which has not otherwise missed out on cosmopolitan perspectives. This observation by Robert W. Rix (2011, 1) accurately assesses what may be considered a significant oversight in studies of the Gothic novel. Whilst it is well known that the ethnic meaning of ‘Gothic’ originally referred to invasive, eastern Germanic, pagan tribes of the third to the sixth centuries AD (see, for example, Sowerby 2000, 15-26), there remains a disconnect between Gothicism as the legacy of Old Norse literature and the use of the term ‘Gothic’ to mean a category of fantastical literature. This essay, then, seeks to complement Rix’s study by, in certain areas, adding more detail about the gradual emergence of Old Norse literature as a significant presence on the European literary scene. The initial focus will be on those formations (often malformations) and interpretations of Old Norse literature as it came gradually to light from the sixteenth century onwards, and how the Nordic Revival impacted on what is widely considered to be the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole (1717-97). -

The Vikings Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE VIKINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Else Roesdahl | 352 pages | 01 Jan 1999 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140252828 | English | London, United Kingdom The Vikings PDF Book Young men were expected to test themselves in this manner. Roam Robotics, a small business located in San Francisco, California, has developed a lightweight and inexpensive knee exoskeleton for Still, Leif established new colonies and even traded with the natives. If a dispute could not be settled, they often resorted to duels or torturous trials known as ordeals [source: Wolf ]. It's best used at 36 points and above to really appreciate the details. And who can blame her? Lagertha Katheryn Winnick , the first wife of Ragnar Lothbrok Travis Fimmel , made quite a name for herself throughout the series. We'll look at the military and nonmilitary technology used by the Vikings in the next section. An elected or appointed official known as a law-speaker acted as an impartial judge to guide the meetings. During Operation Enduring Freedom in late and throughout , forward- deployed S-3B Viking tankers flew more than percent over their normal flight hours underway, enabling air wing strike fighters to reach their assigned kill boxes and return safely to the aircraft carrier from Afghanistan. Sortie rates of 30 missions a day were not uncommon for squadrons operating from carriers in the eastern Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. No whispering over ale in the Great Hall; it's all shouting with this boisterous crew. It is unknown how many real berserkers existed -- they show up most frequently in Nordic sagas as powerful foils for the heroic protagonist [source: Haywood ]. -

Trevor Morris

TREVOR MORRIS COMPOSER Trevor Morris is one of the most prolific and versatile composers in Hollywood. He has scored music for numerous feature films and won two EMMY awards for outstanding composition for his work in Television. Internationally renowned for his music on The Tudors, The Borgias, Vikings and the hit NBC television series Taken, Trevor is a stylistically and musically inventive soundtrack creator. Trevor’s unique musical voice can be heard on his recent film scores which include The Delicacy, Hunter Killer, Asura, Olympus Has Fallen, London Has Fallen, and Immortals. And further Television compositions including Another Life, Condor, Castlevania, The Pillars oF the Earth for Tony and Ridley Scott, Emerald City and Iron Fist for Marvel Television. Trevor has also worked as a co-producer/ conductor/ orchestrator on films including Black Hawk Down, The Last Samurai, The Ring Two, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Batman Begins and collaborated with Tony and Ridley Scott, Neil Jordan, Luc Besson, Jerry Bruckheimer, Antoine Fuqua, Tarsem Singh Dandwar, as well as composers James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer. Trevor is also a Concert Conductor, conducting his music in live concert performances around the globe, including Film Music Festivals in Cordoba Spain, Tenerife Spain, Los Angeles, and Krakow Poland where he conducted a 100-piece orchestra and choir for over 12,000 fans. Trevor has been nominated 5 times for the prestigious EMMY awards, and won twice. As well as being nominated at the World Soundtrack Awards in Ghent for the ‘Discovery of the Year ‘composer award for the film Immortals. Trevor is a British/Canadian dual citizen, based in Los Angeles. -

Register Report Descendants of Adam the First Man of Alfred Landon

Descendants of Adam the First Man Generation 1 1. Adam the First Man-1[1, 2, 3] was born in 4026 BC in Garden of Eden[1, 2, 3]. He died in 3096 BC in Olaha, Shinehah[1, 2]. Eve the First Woman[1, 2] was born in 4025 BC in Garden of Eden[1, 2]. She died in 3074 BC in Eden, ,[1, 2, 3]. Adam the First Man and Eve the First Woman were married about 4022 BC in Garden of Eden[2, 3]. They had the following children: 2. i. Seth ben Adam, Second Patriarch[4] was born in 3874 BC in Olaha, Shileah[1, 2, 4]. He died in 2962 BC in Cainan, East of Eden[1, 2, 3, 4]. ii. Azura Sister[2, 3] was born in Olaha, Shinehah[2, 3]. She died in Canaan,[2, 3]. iii. Noam Ben Adam[2, 3] was born in Eden,[2, 3]. She died in Eden,[2, 3]. iv. Luluwa of Adam[2, 3] was born in Eden,[2, 3]. She died in Eden,[2, 3]. v. Awam ben Adam[2, 3] was born in Eden,[2, 3]. She died in Eden,[2, 3]. vi. Akilia bint Adam[2, 3] was born in Eden,[2, 3]. She died in Eden,[2, 3]. vii. Abel son of Adam[2, 3] was born in Eden,[2, 3]. He died in Eden,[2, 3]. viii. Qalmana[2, 3]. She died in Eden,[2, 3]. ix. Leah bint Adam[2] was born about 4018 BC in Eden[2]. She died about 3100 BC in Eden[2]. -

Thevikingblitzkriegad789-1098.Pdf

2 In memory of Jeffrey Martin Whittock (1927–2013), much-loved and respected father and papa. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people provided valuable advice which assisted in the preparation of this book; without them, of course, carrying any responsibility for the interpretations offered by the book. We are particularly indebted to our agent Robert Dudley who, as always, offered guidance and support, as did Simon Hamlet and Mark Beynon at The History Press. In addition, Bradford-on-Avon library, and the Wiltshire and the Somerset Library services, provided access to resources through the inter-library loans service. For their help and for this service we are very grateful. Through Hannah’s undergraduate BA studies and then MPhil studies in the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic (ASNC) at Cambridge University (2008–12), the invaluable input of many brilliant academics has shaped our understanding of this exciting and complex period of history, and its challenging sources of evidence. The resulting familiarity with Old English, Old Norse and Insular Latin has greatly assisted in critical reflection on the written sources. As always, the support and interest provided by close family and friends cannot be measured but is much appreciated. And they have been patient as meal-time conversations have given way to discussions of the achievements of Alfred and Athelstan, the impact of Eric Bloodaxe and the agendas of the compilers of the 4 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 5 CONTENTS Title Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Gathering