A Thousand Nineteenth-Century Belgian Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

Jubileum‐ En Verjaardagsconcert 1992‐2012 20 Jaar PHAEDRA CD | 20 Jaar in Flanders’ Fields

Jubileum‐ en Verjaardagsconcert 1992‐2012 20 jaar PHAEDRA CD | 20 jaar In Flanders’ Fields Zondag, 28 oktober 2012 om 17u de Blauwe Zaal van de Internationale Kunstcampus deSingel Desguinlei 2018 Antwerpen Liesbeth Devos, sopraan Symfonieorkest Jeugd en Muziek‐Antwerpen Dirigent: Ivo Venkov Presentatie: Katelijne Boon (Radio Klara) Programma: Delen uit het ballet ‘La Phalène’ (de Nachtvlinder) voor orkest – August de Boeck (hercreatie) De Geestelijke Bruiloft, opus 4 (1953)– liedcyclus voor sopraan en orkest op vier romantische gedichten van Pieter Geert Buckinx – Frits Celis (°1929) Cantilene voor sopraan en orkest uit de opera Francesca – August de Boeck Mignon‐Kennst du das Land voor sopraan en orkest – Lodewijk Mortelmans Pauze Beelden uit een Tentoonstelling – Modest Moessorgski/Maurice Ravel Kaarten kosten 10 (tien) euro in voorbestelling; 12 (twaalf) euro de avond zelf aan de kassa Kaarten te bestellen bij: PhaedraCD: [email protected] 0479 873 667 of 03 755 40 37 Betaling van het bedrag met vermelding van het aantal kaarten, naam en adres te gireren op het ibannummer: BE 23 6451 9727 4591 van vzw Klassieke Concerten – Phaedra CD Donkerstraat 51 B ‐ 9120 Beveren www.phaedracd.com Dit concert wordt mede mogelijk gemaakt dank zij de steun van de Internationale Kunstcampus deSingel LIESBETH DEVOS, sopraan www.liesbethdevos.com Tijdens haar opleiding debuteerde de Belgische sopraan Liesbeth Devos in De Munt (Brussel) als Despina in Così fan Tutte. Na dit eerste succes werd ze teruggevraagd voor de vertolking van Ilse in de wereldpremière Frühlingserwachen van Mernier en Papagena in Die Zauberflöte. In 2006 zong Liesbeth Second Woman in Dido and Aeneas onder leiding van Richard Egarr die haar vervolgens uitnodigde voor de Johannes‐Passion met The Academy of Ancient Music in Weimar. -

June 1911) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1911 Volume 29, Number 06 (June 1911) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 29, Number 06 (June 1911)." , (1911). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/570 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 361 THE ETUDE -4 m UP-TO-DATE PREMIUMS _OF STANDARD QUALITY__ K MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. Edited by JAMES FRANCIS COOKE », Alaska, Cuba, Porto Kieo, 50 WEBSTER’S NEW STANDARD 4 DICTIONARY Illustrated. NEW U. S. CENSUS In Combination with THE ETUDE money orders, bank check letter. United States postage ips^are always received for cash. Money sent gerous, and iponsible for its safe T&ke Your THE LAST WORD IN DICTIONARIES Contains DISCONTINUANCE isli the journal Choice o! the THE NEW WORDS Explicit directions Books: as well as ime of expiration, RENEWAL.—No is sent for renewals. The $2.50 Simplified Spelling, „„ ...c next issue sent you will lie printed tile date on wliicli your Webster’s Synonyms and Antonyms, subscription is paid up, which serves as a New Standard receipt for your subscription. -

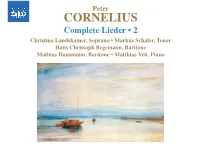

Peter CORNELIUS

Peter CORNELIUS Complete Lieder • 2 Christina Landshamer, Soprano • Markus Schäfer, Tenor Hans Christoph Begemann, Baritone Mathias Hausmann, Baritone • Matthias Veit, Piano Peter CORNELIUS (1824-1874) Complete Lieder • 2 Sechs Lieder, Op. 5 (1861-1862) 16:28 # Abendgefühl (1st version, 1862)** 2:08 1 No. 2. Auf ein schlummerndes Kind** 3:02 (Text: Christian Friedrich Hebbel) (Text: Christian Friedrich Hebbel (1813-1863)) $ Abendgefühl (2nd version, 1863)** 2:40 2 No. 3. Auf eine Unbekannte†† 5:29 (Text: Christian Friedrich Hebbel) (Text: Christian Friedrich Hebbel) 3 No. 4. Ode* 2:34 % Sonnenuntergang (1862)† 2:29 (Text: August von Platen-Hallermünde (1796-1835)) (Text: Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843)) 4 No. 5. Unerhört† 2:45 (Text: Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (1797-1848)) ^ Das Kind (1862)†† 0:52 5 No. 6. Auftrag* 2:38 (Text: Annette von Droste-Hülshoff) (Text: Ludwig Heinrich Christoph Hölty (1748-1776)) & Gesegnet (1862)†† 1:29 † 6 Was will die einsame Träne? (1848) 2:44 (Text: Annette von Droste-Hülshoff) (Text: Heinrich Heine (1797-1856)) * Vision (1865)** 3:30 † 7 Warum sind denn die Rosen so blaß? (c. 1862) 2:04 (Text: August von Platen-Hallermünde) (Text: Heinrich Heine) ( Die Räuberbrüder (1868-1869)† 2:43 †† Drei Sonette (1859-1861) 9:05 (Text: Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857)) (Texts: Gottfried August Bürger (1748-1794)) 8 No. 1. Der Entfernten 2:33 ) Am See (1848)† 2:37 9 No. 2. Liebe ohne Heimat 2:39 (Text: Peter Cornelius) 0 No. 3. Verlust 3:52 ¡ Im tiefsten Herzen glüht mir eine Wunde (1862)† 1:44 ! Dämmerempfindung -

284 XXVII. Tonkünstler-Versammlung Eisenach, 19. – 22. Juni 1890

284 XXVII. Tonkünstler-Versammlung Eisenach, 19. – 22. Juni 1890 1. Aufführung: Erstes Concert [auch: Erstes grosses Concert für Orchester, Soli und Chöre ] Eisenach, Stadt-Theater, Donnerstag, 19. Juni, 18:30 Uhr Ch.: verstärkter Eisenacher Musikverein Ens.: verstärkte Großhzgl. Sächs. Hofkapelle Weimar I. Teil 1. Franz Liszt: Weimars Volkslied, für Männerchor und Ltg.: Eduard Lassen Harmoniemusik Text: Peter Cornelius ( ≡) 2. Prolog Sol.: Paul Friedrich Karl Brock (Rez.) Text: Adolf Stern 3. Engelbert Humperdinck: Das Glück von Edenhall, Ballade Ltg.: Engelbert Humperdinck für Chor und Orchester (EA) Text: Ludwig Uhland ( ≡) 4. Felix Draeseke: Symphonisches Vorspiel zu Heinrich von Ltg.: Richard Strauss Kleists Tragödie Penthesilea 5. Franz Schubert: Ltg.: Hermann Thureau a) „Tantum ergo“, für Soli, Chor und Orchester (Ms., ≡ Sol.: Hedwig Kühn, Auguste Phister, Heinrich lat. und dt.) Zeller, Rudolf von Milde b) Offertorium, für Tenorsolo, Chor und Orchester (Ms., ≡ lat. und dt.) 6. Pëtr Il’i č, Čajkovskij: Serenade für Streichorchester C-Dur Ltg.: Richard Strauss op. 48 Elegie und Finale 7. Johannes Brahms: Schicksalslied, für Chor und Orchester Ltg.: Hermann Thureau Text: Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (≡) II. Teil 8. Franz Liszt: Chöre zu Der entfesselte Prometheus Ltg.: Eduard Lassen Text: Johann Gottfried Herder, verbindende Dichtung: Sol.: Hedwig Kühn, Auguste Phister, Hans Richard Pohl ( ≡) Gießen, Heinrich Zeller, Rudolf von Milde, Ernst Hungar, Paul Friedrich Karl Brock (Rez.) 2. Aufführung: Zweites Concert (Kammermusik-Aufführung) Eisenach, Clemda, Saal, Freitag, 20. Juni, 11:00 Uhr Konzertflügel: Carl Bechstein, Berlin 1. Robert Kahn: Quartett für 2 Violinen, Viola und Sol.: Karl Halir (V.), Theodor Freiberg (V.), Violoncell A-Dur op. 8 Karl Nagel (Va.), Leopold Grützmacher (Vc.) 1. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

R Obert Schum Ann's Piano Concerto in AM Inor, Op. 54

Order Number 0S0T795 Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 54: A stemmatic analysis of the sources Kang, Mahn-Hee, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 U MI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 ROBERT SCHUMANN S PIANO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, OP. 54: A STEMMATIC ANALYSIS OF THE SOURCES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mahn-Hee Kang, B.M., M.M., M.M. The Ohio State University 1992 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Lois Rosow Charles Atkinson - Adviser Burdette Green School of Music Copyright by Mahn-Hee Kang 1992 In Memory of Malcolm Frager (1935-1991) 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the late Malcolm Frager, who not only enthusiastically encouraged me In my research but also gave me access to source materials that were otherwise unavailable or hard to find. He gave me an original exemplar of Carl Relnecke's edition of the concerto, and provided me with photocopies of Schumann's autograph manuscript, the wind parts from the first printed edition, and Clara Schumann's "Instructive edition." Mr. Frager. who was the first to publish information on the textual content of the autograph manuscript, made It possible for me to use his discoveries as a foundation for further research. I am deeply grateful to him for giving me this opportunity. I express sincere appreciation to my adviser Dr. Lois Rosow for her patience, understanding, guidance, and insight throughout the research. -

Choral Singing

Choral Singing Choral Singing: Histories and Practices Edited by Ursula Geisler and Karin Johansson Choral Singing: Histories and Practices, Edited by Ursula Geisler and Karin Johansson This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Ursula Geisler, Karin Johansson and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6331-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6331-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Histories and Practices of Choral Singing in Context Ursula Geisler and Karin Johansson Histories Chapter One ............................................................................................... 14 Little Citizens and Petites Patries: Learning Patriotism through Choral Singing in Antwerp in the Late Nineteenth Century Josephine Hoegaerts Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 33 ‘Ich bin nun getröstet’: Choral Communications in Ein deutsches Requiem Annika Lindskog Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

1041 Katalog.Pdf

PB 1 WWW.PHAEDRACD.COM · 1992 - 2012 Phaedra’s Whys and Wherefores !is catalog simultaneously lists and celebrates the achievements of Phaedra in the twenty years of its existence. At "rst blush publishing just over one hundred CDs in twenty years time may not look impressive. But it is very impressive, as you will see once you know the whys and wherefores of Phaedra. It is the purpose of this introduction to tell you about them. In spite of the .com extension in the URL of its website (www.phaedracd.com), Phaedra is not a commercial undertaking. It is part of a non-pro"t organization, Klassieke Concerten vzw. It was started by one man, and it still is almost entirely the work of one man. He has no sta#, not even a part-time secretary. His o$ce is a room in his house; his storage space, another room. He does everything himself. He decides which music Phaedra will publish, often searching out totally unknown works, including quite a few that are available only as manuscripts. He chooses the performers, in consultation with the composers if these are still alive. He takes care of the logistics of the recording sessions, and of the production process, of the covers and booklets as well as of the CDs proper. He is in charge of all publicity and of marketing Phaedra. It is impossible to justly evaluate the achievements of Phaedra without knowing it is a one-man operation. Like most Flemish non-pro"t organizations, it is also a shoestring operation. -

Romantic Choral Music from Flanders

Romantic Choral Music from Flanders Compiled on the authority of Studiecentrum voor Vlaamse Muziek (SVM) and the Flemish Choral Organisation Koor&Stem by Vic Nees & Michaël Scheck Final editing: Erik Demarbaix, Vic Nees, Liesbeth Segers Music engraving: Dirk Goedseels Afzonderlijke uitgaven van de werken uit deze bundel zijn te verkrijgen bij Musikproduktion Höflich, Munchen [email protected] en Koor&Stem, Antwerpen, [email protected] Separate publications of the works in this anthology can be obtained from Musikproduktion Höflich, München [email protected] and Koor&Stem, Antwerpen, [email protected] Einzelausgaben der in diesem Band enthaltenen Werke sind erhältlich bei Musikproduktion Höflich, München, [email protected] und Koor&Stem, Antwerpen, [email protected] Les oeuvres de ce recueil sont également disponibles en édition séparée chez Musikproduktion Höflich, Munchen [email protected] et chez Koor&Stem, Anvers, [email protected] Although great care has been taken to trace all the sources, it is possible that some have been overlooked. Should this be the case, we apologise to any concerned author or publisher. The required supplements will be respected in future editions. TABLE OF CONTENTS Voorwoord 3 Preface 5 Vorwort 7 Préface 9 François-Auguste Gevaert (1828-1908) Adoro Te 11 Peter Benoit (1834-1901) Ave Maria 14 Jan Blockx (1851-1912) Ave Verum 20 Edgar Tinel (1854-1912) Hoe eenzaam is’t – Wie einsam ist ‘s 22 Emile Wambach (1854-1924) Salve Regina 33 August De Boeck (1865-1937) Ave Maria. Annuntiatio 36 Paul Gilson -

Peter Benoit and the Modern Flemish School

Proceedings of the Musical Association ISSN: 0958-8442 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrma18 Peter Benoit and the Modern Flemish School Prosper Verhevden To cite this article: Prosper Verhevden (1914) Peter Benoit and the Modern Flemish School, Proceedings of the Musical Association, 41:1, 17-35, DOI: 10.1093/jrma/41.1.17 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jrma/41.1.17 Published online: 28 Jan 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 4 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrma18 Download by: [Athabasca University] Date: 07 June 2016, At: 02:49 T. LEA SOUTHGATE, EsQ., D.C.L., PETER BENOIT AND THE MODERN FLEMISH SCHOOL. Downloaded by [Athabasca University] at 02:49 07 June 2016 YOUmay, perhaps, think it over-bold of me to talk tw you in your own language, which, in my mouth, will appear without its native richness, shength, and beauty. You will at once realise that you have before you a man who did not want to come and call for your attention a short time ago, but now is willii to suffer the cruel consciousness of being a poor orator, if only he succeeds, though but partially, in his attempt to give you an idea of one of the aspects of beauty in his own beloved country. A perfect command of a foreign language enables one to communicate with foreigners on all subjects of intellectual interest ; but only in one's own tongue is it possible to utter one's deepest feelings, those which lind their strongest expression in art. -

![103 Musikertag Magdeburg, 15. [16.] – 18. September 1871](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5324/103-musikertag-magdeburg-15-16-18-september-1871-2505324.webp)

103 Musikertag Magdeburg, 15. [16.] – 18. September 1871

103 Musikertag Magdeburg, 15. [16.] – 18. September 1871 1. Aufführung: Großes Concert für Instrumental- und Vocal-Vorträge, veranstaltet vom Allgemeinen deutschen Musikverein Magdeburg, Johanniskirche, Samstag, 16. September, 18:30 – nach 21:00 Uhr Ltg.: Gustav Rebling Org.: Sauer, Frankfurt (Oder) 1. August Gottfried Ritter: Freier Vortrag auf der Orgel Sol.: August Gottfried Ritter (Org.) 2. Hermann Zopff: Religiöse Gesänge für Tenor, Orgel, Sol.: Johannes Müller (T), Brand (Org.), Bohne Violine und Viola (a) V.), Heinrich Klesse (a) Va.) a) Pfingstgruss Text: Luise Otto (≡) b) In stillen Stunden Text: Moritz Alexander Zille (≡) 3. Gustav Rebling: Der 12. Psalm für 8stimmigen Chor a Ch.: Reblingscher Kirchengesangverein capella op. 13 Nr. 1 ( ≡ dt.) 4. Hans Bronsart von Schellendorff: Fantasiestück für Sol.: Robert Heckmann (V.), Brand (Org.) Violine und Orgel 5. Peter Cornelius: „Von dem Dome schwer und bang“, Ch.: Magdeburger Liedertafel II Trauerchor für Männerstimmen Text: Friedrich von Schiller, aus Die Glocke ( ≡) ---- 6. Gustav Adolf Merkel: Adagio für Violoncello und Orgel Sol.: Leopold Grützmacher (Vc.), Rudolf Palme (Org.) 7. Eduard Lassen: Palmblätter, für Solostimmen und Sol.: Anna Worgitzka (S), Bertha Dotter (A), Begleitung Johannes Müller (T), Leopold Müller (B), Text: Karl Gerok Robert Ravenstein (a) B), Rudolf Palme (Org.), 2 Gesänge ( ≡) Müller (Hr.), Adolf Hankel (Hf.) a) Bethanien, für Sopran, Alt, Tenor, 2 Bässe und Orgel- Begleitung b) In Joseph’s Garten, für Alt, Tenor und Bass-Solo mit Begleitung von Orgel, Horn und Harfe 8. Friedrich Kiel: Fantasie für Orgel h-Moll op. 58 Nr. 2 Sol.: Gustav Rebling (Org.) 1. Maestoso 2. Recitativo 3. Tema con Variazione ---- 9. Franz Liszt: Missa choralis, für Chor, Solostimmen und Sol.: Anna Worgitzka (S), Bertha Dotter (A), Orgel ( ≡ lat.