China's Renminbi Currency Logistics Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download to View

The Mao Era in Objects Money (钱) Helen Wang, The British Museum & Felix Boecking, University of Edinburgh Summary In the early twentieth century, when the Communists gained territory, they set up revolutionary base areas (also known as soviets), and issued new coins and notes, using whatever expertise, supplies and technology were available. Like coins and banknotes all over the world, these played an important role in economic and financial life, and were also instrumental in conveying images of the new political authority. Since 1949, all regular banknotes in the People’s Republic of China have been issued by the People’s Bank of China, and the designs of the notes reflect the concerns of the Communist Party of China. Renminbi – the People’s Money The money of the Mao era was the renminbi. This is still the name of the PRC's currency today - the ‘people’s money’, issued by the People’s Bank of China (renmin yinhang 人民银 行). The ‘people’ (renmin 人民) refers to all the people of China. There are 55 different ethnic groups: the Han (Hanzu 汉族) being the majority, and the 54 others known as ethnic minorities (shaoshu minzu 少数民族). While the term renminbi (人民币) deliberately establishes a contrast with the currency of the preceding Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek, the term yuan (元) for the largest unit of the renminbi (which is divided into yuan, jiao 角, and fen 分) was retained from earlier currencies. Colloquially, the yuan is also known as kuai (块), literally ‘lump’ (of silver), which establishes a continuity with the silver-based currencies which China used formally until 1935 and informally until 1949. -

Globalised Knowledge Flows and Chinese

Paradoxical Integration: Globalised Knowledge Flows and Chinese Concepts in Social Theory Xiaoying Qi A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Cultural Research University of Western Sydney 2011 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the support I have received from a number of people during the research and writing of this PhD thesis. I am grateful to my principal supervisor, Associate Professor Greg Noble, for his support for my application for funds to attend and present a paper at the International Sociological Association XVII World Congress of Sociology in 2010 and for his close reading and detailed comments on the draft and revised chapters, which led to many improvements. My associate supervisor, Professor Peter Hutchings, is thanked for his comments on draft chapters. My gratitude also goes to the three anonymous reviewers of a paper, „Face: A Chinese Concept in a Global Sociology‟, which was published in the Journal of Sociology in 2011. This paper prefigures the arguments of chapter 5. I am also grateful to the University of Western Sydney for granting me a scholarship and for providing me with an opportunity to undertake the research reported and discussed in this thesis. I must also acknowledge the support I received from the staff of the UWS library system, and its inter-library loan provision. The most enduring support I received during the period of research and writing of this thesis was provided by my family. I thank my parents and sister for their belief in my ability and their continuing encouragement. Last but by no means least I thank my husband, Jack Barbalet, for his unfailing love, inspiration, encouragement, guidance, advice and support. -

CHINA TODAY China’S Importance on the Global Landscape in Indisputable

02.2016 Certified International Property Specialist TO LOCAL, INTERNATIONAL & LIFESTYLE REAL ESTATE > UPDATE ON CHINA What Global Agents Need to Know About CHINA TODAY China’s importance on the global landscape in indisputable. Its purchasing power, amplifi ed by several years of strong economic growth and the sheer size of its population is felt across the globe. Chinese investors—including individuals, corporations, and institutions—have all displayed a strong appetite for real property beyond their borders. Will the trend continue in 2016? Probably, yes. Even though the country’s roaring economic engine has cooled, there are many reasons to expect overseas property purchases to remain strong. In fact, some segments of the market and destinations may witness even more robust interest. That’s because, as a rule, Chinese buyers do their homework. If the numbers don’t add up because prices are too high, they’ll explore other locations. At the same time, Chinese buyers are also well represented in the global luxury market, where sky-high prices are seldom deal-breakers. As a nation, China has been taking signifi cant steps aimed at more fully joining the world’s economic leaders. Even if you aren’t directly aff ected by these developments, it’s important to be informed about them, especially if you’re working with Chinese clients. This issue will get you up to speed. Inside, you’ll also fi nd an update on the latest overseas buying trends among Chinese investors—tips that can be extremely benefi cial in marketing to and working with clients. PROPERTYUPDATE ON PORTALSPO CHINATA KEY ECONOMIC & FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS IN CHINA Just over a year ago, China overtook the U.S. -

Submitted for the Phd Degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

THE CHINESE SHORT STORY IN 1979: AN INTERPRETATION BASED ON OFFICIAL AND NONOFFICIAL LITERARY JOURNALS DESMOND A. SKEEL Submitted for the PhD degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1995 ProQuest Number: 10731694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731694 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 A b s t ra c t The short story has been an important genre in 20th century Chinese literature. By its very nature the short story affords the writer the opportunity to introduce swiftly any developments in ideology, theme or style. Scholars have interpreted Chinese fiction published during 1979 as indicative of a "change" in the development of 20th century Chinese literature. This study examines a number of short stories from 1979 in order to determine the extent of that "change". The first two chapters concern the establishment of a representative database and the adoption of viable methods of interpretation. An important, although much neglected, phenomenon in the make-up of 1979 literature are the works which appeared in so-called "nonofficial" journals. -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

Representations of Cities in Republican-Era Chinese Literature

Representations of Cities in Republican-era Chinese Literature Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hao Zhou, B.A. Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Kirk A. Denton, Advisor Heather Inwood Copyright by Hao Zhou 2010 Abstract The present study serves to explore the relationships between cities and literature by addressing the issues of space, time, and modernity in four works of fiction, Lao She’s Luotuo xiangzi (Camel Xiangzi, aka Rickshaw Boy), Mao Dun’s Ziye (Midnight), Ba Jin’s Han ye (Cold nights), and Zhang Ailing’s Qingcheng zhi lian (Love in a fallen city), and the four cities they depict, namely Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, and Hong Kong, respectively. In this thesis I analyze the depictions of the cities in the four works, and situate them in their historical and geographical contexts to examine the characteristics of each city as represented in the novels. In studying urban space in the literary texts, I try to address issues of the “imaginablity” of cities to question how physical urban space intertwines with the characters’ perception and imagination about the cities and their own psychological activities. These works are about the characters, the plots, or war in the first half of the twentieth century; they are also about cities, the human experience in urban space, and their understanding or reaction about the urban space. The experience of cities in Republican era fiction is a novel one, one associated with a new modern historical consciousness. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Xi Tian August 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson Dr. Paul Pickowicz Dr. Yenna Wu Copyright by Xi Tian 2014 The Dissertation of Xi Tian is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 by Xi Tian Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, August 2014 Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson My dissertation rethinks satire and redefines our understanding of it through the examination of works from the 1930s and 1940s. I argue that the fluidity of satiric writing in the 1930s and 1940s undermines the certainties of the “satiric triangle” and gives rise to what I call, variously, self-satire, self-counteractive satire, empathetic satire and ambiguous satire. It has been standard in the study of satire to assume fixed and fairly stable relations among satirist, reader, and satirized object. This “satiric triangle” highlights the opposition of satirist and satirized object and has generally assumed an alignment by the reader with the satirist and the satirist’s judgments of the satirized object. Literary critics and theorists have usually shared these assumptions about the basis of satire. I argue, however, that beginning with late-Qing exposé fiction, satire in modern Chinese literature has shown an unprecedented uncertainty and fluidity in the relations among satirist, reader and satirized object. -

Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham

Victorianizing Guangxu: Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham Scott Relyea, Appalachian State University Abstract In the late Qing and early Republican eras, eastern Tibet (Kham) was a borderland on the cusp of political and economic change. Straddling Sichuan Province and central Tibet, it was coveted by both Chengdu and Lhasa. Informed by an absolutist conception of territorial sovereignty, Sichuan officials sought to exert exclusive authority in Kham by severing its inhabitants from regional and local influence. The resulting efforts to arrest the flow of rupees from British India and the flow of cultural identity entwined with Buddhism from Lhasa were grounded in two misperceptions: that Khampa opposition to Chinese rule was external, fostered solely by local monasteries as conduits of Lhasa’s spiritual authority, and that Sichuan could arrest such influence, the absence of which would legitimize both exclusive authority in Kham and regional assertions of sovereignty. The intersection of these misperceptions with the significance of Buddhism in Khampa identity determined the success of Sichuan’s policies and the focus of this article, the minting and circulation of the first and only Qing coin emblazoned with an image of the emperor. It was a flawed axiom of state and nation builders throughout the world that severing local cultural or spiritual influence was possible—or even necessary—to effect a borderland’s incorporation. Keywords: Sichuan, southwest China, Tibet, currency, Indian rupee, territorial sovereignty, Qing borderlands On December 24, 1904, after an arduous fourteen-week journey along the southern road linking Chengdu with Lhasa, recently appointed assistant amban (Imperial Resident) to Tibet Fengquan reached Batang, a lush green valley at the western edge of Sichuan on the province’s border with central Tibet. -

Cultural Notes on Chinese Negotiating Behavior Working Paper

Cultural Notes on Chinese Negotiating Behavior James K. Sebenius Cheng (Jason) Qian Working Paper 09-076 Copyright © 2008 by James K. Sebenius and Cheng (Jason) Qian Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Cultural Notes on Chinese Negotiating Behavior James K. Sebenius ([email protected]) Cheng (Jason) Qian ([email protected]) Harvard Business School, Boston, MA USA December 24, 2008 “ He who knows his enemy and himself well will not be defeated easily.” — Sun Tzu, Art of War Western businesses negotiating with Chinese firms face many challenges, from initiating and smoothing communication to establishing long-lasting relationships and mutual trust, and from bargaining and drafting agreements to securing their implementation. Chinese negotiators can be at once warm hosts and friends and tough bargainers. Unique Chinese cultural elements such as complicated local etiquette, obscured decision-making processes, and heavy reliance on interpersonal relationships instead of legal instruments all add to the complexities of Sino-foreign business negotiations, and can make the process tiresome and protracted. Besides talking past each other, Chinese and western negotiators often harbor mutually unfavorable perceptions. Many westerners find Chinese negotiators to be inefficient, indirect, and even dishonest; Chinese negotiators frequently perceive their western counterparts to be aggressive, impersonal, and insincere. The way to decipher the Chinese negotiating style and bring about mutually beneficial results is to better understand the key elements of Chinese culture to which Chinese negotiators attune their business mentality and manners. -

Chinese Zheng and Identity Politics in Taiwan A

CHINESE ZHENG AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN TAIWAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2018 By Yi-Chieh Lai Dissertation Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Byong Won Lee R. Anderson Sutton Chet-Yeng Loong Cathryn H. Clayton Acknowledgement The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. First of all, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Frederick Lau, for his professional guidelines and mentoring that helped build up my academic skills. I am also indebted to my committee, Dr. Byong Won Lee, Dr. Anderson Sutton, Dr. Chet- Yeng Loong, and Dr. Cathryn Clayton. Thank you for your patience and providing valuable advice. I am also grateful to Emeritus Professor Barbara Smith and Dr. Fred Blake for their intellectual comments and support of my doctoral studies. I would like to thank all of my interviewees from my fieldwork, in particular my zheng teachers—Prof. Wang Ruei-yu, Prof. Chang Li-chiung, Prof. Chen I-yu, Prof. Rao Ningxin, and Prof. Zhou Wang—and Prof. Sun Wenyan, Prof. Fan Wei-tsu, Prof. Li Meng, and Prof. Rao Shuhang. Thank you for your trust and sharing your insights with me. My doctoral study and fieldwork could not have been completed without financial support from several institutions. I would like to first thank the Studying Abroad Scholarship of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan and the East-West Center Graduate Degree Fellowship funded by Gary Lin. -

About Beijing

BEIJING Beijing, the capital of China, lies just south of the rim of the Central Asian Steppes and is separated from the Gobi Desert by a green chain of mountains, over which The Great Wall runs. Modern Beijing lies on the site of countless human settlements that date back half a million years. Homo erectus Pekinensis, better known as Peking man was discovered just outside the city in 1929. It is China's second largest city in terms of population and the largest in administrative territory. The name Beijing - or Northern Capital - is a modern term by Chinese standards. It first became a capital in the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), but it experienced its first phase of grandiose city planning in the Yuan Dynasty under the rule of the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, who made the city his winter capital in the late 13th century. Little of it remains in today's Beijing. Most of what the visitor sees today dates from either the Ming or later Qing dynasties. Huge concrete tower blocks have mushroomed and construction sites are everywhere. Bicycles are still the main mode of transportation but taxis, cars, and buses jam the city streets. PASSPORT/VISA CONDITIONS All visitors to Beijing and the People's Republic of China are required to have a valid passport (one that does not expire for at least 6 months after your arrival date in China). A special tourist or business visa is also required. CUSTOMS Travelers are allowed to bring into China one bottle of alcoholic beverages and two cartons of cigarettes. -

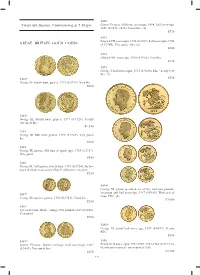

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2).