Michelangelo String Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

Michael Brecker Chronology

Michael Brecker Chronology Compiled by David Demsey • 1949/March 29 - Born, Phladelphia, PA; raised in Cheltenham, PA; brother Randy, sister Emily is pianist. Their father was an attorney who was a pianist and jazz enthusiast/fan • ca. 1958 – started studies on alto saxophone and clarinet • 1963 – switched to tenor saxophone in high school • 1966/Summer – attended Ramblerny Summer Music Camp, recorded Ramblerny 66 [First Recording], member of big band led by Phil Woods; band also contained Richie Cole, Roger Rosenberg, Rick Chamberlain, Holly Near. In a touch football game the day before the final concert, quarterback Phil Woods broke Mike’s finger with the winning touchdown pass; he played the concert with taped-up fingers. • 1966/November 11 – attended John Coltrane concert at Temple University; mentioned in numerous sources as a life-changing experience • 1967/June – graduated from Cheltenham High School • 1967-68 – at Indiana University for three semesters[?] • n.d. – First steady gigs r&b keyboard/organist Edwin Birdsong (no known recordings exist of this period) • 1968/March 8-9 – Indiana University Jazz Septet (aka “Mrs. Seamon’s Sound Band”) performs at Notre Dame Jazz Festival; is favored to win, but is disqualified from the finals for playing rock music. • 1968 – Recorded Score with Randy Brecker [1st commercial recording] • 1969 – age 20, moved to New York City • 1969 – appeared on Randy Brecker album Score, his first commercial release • 1970 – co-founder of jazz-rock band Dreams with Randy, trombonist Barry Rogers, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Doug Lubahn. Recorded Dreams. Miles Davis attended some gigs prior to recording Jack Johnson. -

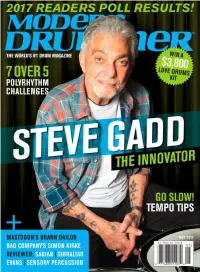

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets

HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America Volume 9 Number 1 Spring 2019 Article 2 March 2019 Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets Matthew J. Hall Cornell University Follow this and additional works at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal Recommended Citation Hall, Matthew J. (2019) "Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets," HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America: Vol. 9 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal/vol9/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Media and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America by an authorized editor of Research Media and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Hall, Matthew. “Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn’s String Quartets.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 9.1 (Spring 2019), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2019. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn’s String Quartets By Matthew J. Hall Cornell University Abstract The predominance of major-mode works in the repertoire corresponds with the view that minor-mode works are exceptions to a major-mode norm. For example, Charles Rosen’s Sonata Forms, James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s Sonata Theory, and William Caplin’s Classical Form all theorize from the perspective of a major-mode default. -

1) Aspects of the Musical Careers of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel

Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Biographical issues and a comparison of their string quartets Juliette L. Appold I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects II. Connections between Grieg, Debussy and Ravel III. Observations on their string quartets I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects Looking at the biographies of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel makes us realise, that there are few, yet some similarities in the way their career as composers were shaped. In my introductory paragraph I will point out some of these aspects. The three composers received their first musical training in their childhood, between the age of six (Grieg) and nine (Debussy) (Ravel was seven). They all entered the conservatory in their early teenage years (Debussy was 10, Ravel 14, Grieg 15 years old) and they all had more or less difficult experiences when they seriously thought about a musical career. In Grieg’s case it happened twice in his life. Once, when a school teacher ridiculed one of his first compositions in front of his class-mates.i The second time was less drastic but more subtle during his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory until 1862.ii Grieg had despised the pedagogical methods of some teachers and felt that he did not improve in his composition studies or even learn anything.iii On the other hand he was successful in his piano-classes with Carl Ferdinand Wenzel and Ignaz Moscheles, who had put a strong emphasis on the expression in his playing.iv Debussy and Ravel both were also very good piano players and originally wanted to become professional pianists. -

Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia Or Online at Wrti.Org

Next on Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia or online at wrti.org. Encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series every Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. on WRTI-HD2 Saturday, August 4th, 2012, 5:00-6:00 p.m. Claude Debussy (1862-1918). Danse (Tarantelle styrienne) (1891, 1903). David Allen Wehr, piano. Connoiseur Soc 4219, Tr 4, 5:21 Debussy. Danse, orch. Ravel (1923). Philharmonia Orchestra, Geoffrey Simon. Cala 1024, Tr 9, 5:01 Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Shéhérazade (1903). Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano, Cleveland Orchestra, Pierre Boulez. DG 2121, Tr 1-3, 17:16 Ravel. Introduction and Allegro (1905). Rachel Masters, harp, Christopher King, clarinet, Ulster Orchestra, Yan Pascal Tortelier. Chandos 8972, Tr 7, 11:12 Debussy. Sarabande, from Pour le piano (1901). Larissa Dedova, piano. Centaur 3094, Disk 4, Tr 6, 4:21 Debussy. Sarabande, orch. Ravel (1923). Ulster Orchestra, Yan Pascal Tortelier. Chandos 9129, Tr 2, 4:29 This time, he’d show them. The Paris Conservatoire accepted Ravel as a piano student at age 16, and even though he won a piano competition, more than anything he wanted to compose. But the Conservatory was a hard place. He never won the fugue prize, never won the composition prize, never won anything for writing music and they sent him packing. Twice. He studied with the great Gabriel Fauré, in school and out, but he just couldn’t make any headway with the ruling musical authorities. If it wasn’t clunky parallelisms in his counterpoint, it was unresolved chords in his harmony, but whatever the reason, four times he tried for the ultimate prize in composition, the Prix de Rome, and four times he was refused. -

4474134-09A1a4-Booklet-CD98.626

2.K ach intensiver Auseinandersetzung mit dem er „kritische Bericht“, dieser Inbegriff Symbole werden zu Akteuren eines unserer Nsinfonischen Werk Mozarts und Beethovens Dgeduldigsten Forscherfleißes, begegnet Imagination entspringenden Theaters und habe ich meine Liebe zu Haydns Musik zugege- abseits seines Fachbezirks vielfachem Unver- treten, vielleicht auch nur für ein paar Minu- benermaßen erst relativ spät entdeckt. Seither ist ständnis. All diese Hieroglyphen und Linea- ten, wieder ins Rampenlicht einstiger Pracht es mir ein Anliegen, „Papa Haydn“ den Zopf abzu- mente, die vom Schreiber X zur Quelle Y, & Herrlichkeit. Wer war denn wohl der Ko- schneiden, den ihm das 19. und 20. Jahrhundert von zweifelhaften Wasserzeichen zu unech- pist, wer waren die fleißigen Leute, die dem haben wachsen lassen. Die Gesamteinspielung der ten Tintensorten führen – diese kryptischen Hofkapellmeister des Fürsten Nikolaus von Haydn-Sinfonien ist für meine Musiker und mich Überlieferungsnachweise und Stammbäume, Eszterházy bei seiner unablässigen Produkti- eine höchst interessante Aufgabe und eine große fachlich korrekter als „Stemmata“ bezeich- on zur Hand gingen? Für wen notierte Herausforderung, bietet sich doch mit diesem ehr- net: Müssen wir uns wirklich jede noch so „Schreiber F“, wenn ihm noch ein paar geizigen Projekt die einmalige Chance, die Ent- hypothetische Frage stellen lassen, ehe uns Nachtstunden blieben, einen zweiten Stim- wicklung der klassischen Sinfonie hautnah nachzu- die Kontaktaufnahme mit dem eigentlichen mensatz? Wie viele Kreutzer mag er dafür erleben. In Zeiten musikalischen (und gesellschaft- Notentext gestattet wird? bekommen, wen davon möglicherweise er- DEUTSCH lichen) Wandels war Haydn Stürmer, Dränger, Das hängt von der eigenen Art der Be- nährt haben? War’s seine Fehlsichtigkeit, Sucher und Finder zugleich. -

Brentano String Quartet

“Passionate, uninhibited, and spellbinding” —London Independent Brentano String Quartet Saturday, October 17, 2015 Riverside Recital Hall Hancher University of Iowa A collaboration with the University of Iowa String Quartet Residency Program with further support from the Ida Cordelia Beam Distinguished Visiting Professor Program. THE PROGRAM BRENTANO STRING QUARTET Mark Steinberg violin Serena Canin violin Misha Amory viola Nina Lee cello Selections from The Art of the Fugue Johann Sebastian Bach Quartet No. 3, Op. 94 Benjamin Britten Duets: With moderate movement Ostinato: Very fast Solo: Very calm Burlesque: Fast - con fuoco Recitative and Passacaglia (La Serenissima): Slow Intermission Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 67 Johannes Brahms Vivace Andante Agitato (Allegretto non troppo) Poco Allegretto con variazioni The Brentano String Quartet appears by arrangement with David Rowe Artists www.davidroweartists.com. The Brentano String Quartet record for AEON (distributed by Allegro Media Group). www.brentanoquartet.com 2 THE ARTISTS Since its inception in 1992, the Brentano String Quartet has appeared throughout the world to popular and critical acclaim. “Passionate, uninhibited and spellbinding,” raves the London Independent; the New York Times extols its “luxuriously warm sound [and] yearning lyricism.” In 2014, the Brentano Quartet succeeded the Tokyo Quartet as Artists in Residence at Yale University, departing from their fourteen-year residency at Princeton University. The quartet also currently serves as the collaborative ensemble for the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The quartet has performed in the world’s most prestigious venues, including Carnegie Hall and Alice Tully Hall in New York; the Library of Congress in Washington; the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam; the Konzerthaus in Vienna; Suntory Hall in Tokyo; and the Sydney Opera House. -

Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz

Classics & Jazz PAID Permit # 79 PRSRT STD PRSRT Late Fall 2020 U.S. Postage Aberdeen, SD Jazz New Naxos Bundle Deal Releases 3 for $30 see page 54 beginning on page 10 more @ more @ HBDirect.com HBDirect.com see page 22 OJC Bundle Deal P.O. Box 309 P.O. 05677 VT Center, Waterbury Address Service Requested 3 for $30 see page 48 Classical 50% Off beginning on page 24 more @ HBDirect.com 1/800/222-6872 www.hbdirect.com Classical New Releases beginning on page 28 more @ HBDirect.com Love Music. HBDirect Classics & Jazz We are pleased to present the HBDirect Late Fall 2020 Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz Catalog, with a broad range of offers we’re sure will be of great interest to our customers. Catalog Index Villa-Lobos: The Symphonies / Karabtchevsky; São Paulo SO [6 CDs] In jazz, we’re excited to present another major label as a Heitor Villa-Lobos has been described as ‘the single most significant 4 Classical - Boxed Sets 3 for $30 bundle deal – Original Jazz Classics – as well as a creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music.’ The eleven sale on Double Moon, recent Enlightenment boxed sets and 10 Classical - Naxos 3 for $30 Deal! symphonies - the enigmatic Symphony No. 5 has never been found new jazz releases. On the classical side, HBDirect is proud to 18 Classical - DVD & Blu-ray and may not ever have been written - range from the two earliest, be the industry leader when it comes to the comprehensive conceived in a broadly Central European tradition, to the final symphony 20 Classical - Recommendations presentation of new classical releases. -

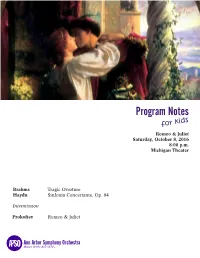

Program Notes

Program Notes for kids Romeo & Juliet Saturday, October 8, 2016 8:00 p.m. Michigan Theater Brahms Tragic Overture Haydn Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 84 Intermission Prokofiev Romeo & Juliet Tragic Overture by Johannes Brahms What kind of piece is this? This piece is a concert overture, similar to the overture of an opera. An opera overture is the opening instrumental movement that signals to the audience that the perfor- mance is about to begin. Similarily, a concert overture is a short and lively introduction to an instrumental con- cert. When was it written? Brahms wrote this piece in the summer of 1880 while on vacation. Brahms at the Piano What is it about? Brahms was a quiet and sad person, and really wanted to compose a piece about a tragedy. With no particular tragedy in mind, he created this overture as a contrast to his much happier Academic Festival Overture, which he completed in the same summer. When describing the two overtures to a friend, Brahms said “One of them weeps, the other laughs.” About the Composer Fun Facts Johannes Brahms | Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Ger- Brahms never really grew up. He didn’t many | Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria care much about how he looked, he left his clothes lying all over the floor Family & Carfeer of his house, he loved merry-go-rounds and circus sideshows, and he continued Brahms’ father, Johann Jakob Brahms, was a bierfiedler: playing with his childhood toys until he literally, a “beer fiddler” who played in small bands at was almost 30 years old. -

Beethoven's Middle and Late String Quartets

Chamber Music Seminar: Prof. Edward A. Parson, Michigan Law School, 2007-2008: Notes for the Fourth Session, January 16, 2008: Middle and Late Beethoven Quartets In this session, we’ll hear two great string quartets of Beethoven – one from his middle period – the period from about 1803 to 1813, sometimes called his “heroic decade,” in which he wrote a ton of his most famous and popular works; and one of late quartets – five astonishing quartets plus a large left-over movement called “the great fugue.” These were his last major works, from the last three years of his life. (He died in 1827, aged 57) (Recall for context – Beethoven wrote 16 string quartets: the bundle of six in his youth, opus 18, of which we heard one last session; the five of his middle period; and five plus the great fugue from the end of his life). I’ll be joined by three advanced performance students from the UM School of Music, Theatre, and Dance: Rachel Patrick (violin), Marcus Scholtes (violin), and Tom Carter (viola). Quartet in E minor, Opus 59 No. 2: The first one we’ll hear tonight is one of a group of three quartets written in 1805 and 1806 on a commission from Prince Andrey Rasumovsky, the Russian ambassador to Vienna – and known as the “Rasumovsky” quartets. You can use your wealth to buy immortality, if you’re careful enough what you spend it on. Rasumovsky was a talented dilettante (and pretty good violinist), an admirer and sponsor of culture and science, and a libertine. The posting of ambassador in Vienna, the most culturally vibrant city in Europe, suited him perfectly – but as an associate wrote, “Rasumovsky lived in Vienna on a princely scale, encouraging art and science, surrounded by a valuable library and other collections, and admired or envied by all; of what advantage this was to Russian interests is, however, another question.” He commissioned these quartets to mark his taking over from a friend the patronage of the best string quartet in Vienna – the ensemble led by, and named for, Ignaz Schuppanzigh, which gave the first performance of most of Beethoven’s quartets. -

GIOCOSO QUARTET Thursday 5 April 2018, 8Pm Hobart Town Hall

GIOCOSO QUARTET Thursday 5 April 2018, 8pm Hobart Town Hall Programme Joseph HAYDN (1732-1809) String Quartet in D major, op 71 no 2 (1793) 19 min I Adagio – allegro II Adagio cantabile III Menuetto: Allegretto – Trio IV Finale: Allegretto Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856) String Quartet no 1 in A minor, op 41 no 1 (1842) 26 min I Andante espressivo-Allegro II Scherzo: Presto III Adagio IV Allegro INTERVAL Maurice RAVEL (1875-1937) String Quartet in F major (1902-03) 28 min I Allegro moderato II Assez vif, très rythmé III Très lent IV Vif et agité Programme Notes Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) String Quartet in D major, op 71 no 2 (1793) I Adagio - Allegro II Adagio cantabile III Menuetto: Allegro & Trio IV Finale: Allegretto – Allegro Upon his triumphal return to London in February 1794, Haydn brought with him one whole symphony (no 99), parts for two others (nos 100 &101) and six new string quartets, soon to be known as op 71 and 74 (because they were issued in two sets, each one provided, wrongly with a separate opus number). The quartets were destined to serve as a double purpose. They had been commissioned by an old friend and patron, Anton Georg, Count von Apponyi, a Freemason who sponsored Haydn's entrance into the Craft in 1785. It was customary for a commissioner to have exclusive performing rights of such works for a period of years, but in this case Haydn obviously intended the works - completed and delivered only in the previous year, 1793 - not so much for the limited circle of Apponyi and his Austrian friends, as for the forthcoming season in the fashionable concert rooms of his London impresario, the violinist Johann Peter Salomon.