Reshaping Remembrance ~ the Voortrekker in Search of New Horizons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissertation Terre Blanche Hj.Pdf

IDEOLOGIES AFFECTING UPPER AND MIDDLE CLASS AFRIKANER WOMEN IN JOHANNESBURG, 1948, 1949 AND 1958 by HELEN JENNIFER TERRE BLANCHE submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF A M GRUNDLINGH JOINT SUPERVISOR: DR D PRINSLOO NOVEMBER 1997 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record my thanks to my supervisor and joint supervisor who generously gave of their time and knowledge. Prof Albert Grundlingh was unfailingly helpful and patient, and Dr Dione Prinsloo kindly allowed me to make use of interviews she had conducted. Her knowledge of the Afrikaner community in Johannesburg was also invaluable. I would also like to thank my family, my husband, for his comments and proofreading, my mother for the proofreading of the final manuscript, and my children, Sara and Ruth, for their patience and tolerance. I would also like to thank my father for encouraging my interest in history from an early age. Thanks are also due to Mrs Renee d'Oiiveira, headmistress of Loreto Convent, Skinner street, for her interest in my studies and her support. 305.483936068221 TERR UNISA BI8Lf0Tt:;~:: / LIBRARY Class Klas ... Access Aanwin ... 111111111111111 0001705414 Student number: 460-005-3 I declare that "Ideologies affecting upper and middle class Afrikaner women in Johannesburg, 1948, 1949 a.nd 1958" is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references . .. ;//.-.! ~~~a.~q~~ ......... SIGNATURE DATE (H J TERRE BLANCHE) SUMMARY This thesis investigates discourses surrounding upper and middle class Afrikaner women living in Johannesburg during the years 1948, 1949 and 1958. -

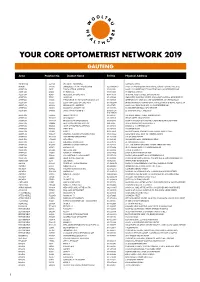

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

334 Chapter 10 Natal Afrikaner Women and The

University of Pretoria etd – Wassermann, J M (2005) 334 CHAPTER 10 NATAL AFRIKANER WOMEN AND THE ANGLO-BOER WAR The role and plight of the Republican Afrikaner women have always formed an integral, and sometimes even central part of the historiography of the Anglo-Boer War. The emphasis in the large number of academic and popular works and published memoirs invariably falls on the suffering of Afrikaner women and children in the concentration camps. Despite this volume of work, Helen Bradford1 maintains that one of the seminal questions faced by the historiography of the Anglo-Boer War is the neglect of the unique war experiences of women. One group previously neglected was Natal Afrikaner women who formed a stratified and diverse group. Some, like MJ Zietsman of Snelster near Estcourt, whose daughter, the widow Wallace had been to England and who kept thoroughbred Pointers, were wealthy and sophisticated.2 Another, like ME Kock, read Tennyson and Shakespeare,3 while Emily Pieters owned 20 bound music books for playing the piano and harmonium.4 On the other end of the social scale were women like Annie Katrina Slabbert of Dundee who sewed and took in laundry to survive.5 These class differences were underpinned by the patriarchal system in which the women functioned. Married women had the least power and received little support or recognition from the authorities. In contrast widows wielded much more economic and political power and were also able to generate letters and other documents.6 However, regardless of their educational, social, economic or marital status, most Natal Afrikaner women suffered, in one way or another, during the war. -

South Africa and Russia (1890–2010)

Viewing ‘the other’ over a hundred and a score more years: South Africa and Russia (1890–2010) I LIEBENBERG* Abstract Whether novel is history or history is novel, is a tantalising point. “The novel is no longer a work, a thing to make last, to connect the past with the future but (only) one current event among many, a gesture with no tomorrow” Kundera (1988:19). One does not have to agree with Kundera to find that social sciences, as historiography holds a story, a human narrative to be shared when focused on a case or cases. In this case, relations between peoples over more than a century are discussed. At the same time, what is known as broader casing in qualitative studies enters the picture. The relations between the governments and the peoples of South Africa and Russia (including the Soviet Union), sometimes in conflict or peace and sometimes at variance are discussed. Past and present communalities and differences between two national entities within a changing international or global context deserve attention while moments of auto-ethnography compliment the study. References are made to the international political economy in the context of the relations between these countries. Keywords: Soviet Union, South Africa, Total Onslaught, United Party, Friends of the Soviet Union, ideological conflict (South Africa), Russians (and the Anglo-Boer War), racial capitalism, apartheid, communism/Trotskyism (in South Africa), broader casing (qualitative research) Subject fields: political science, sociology, (military) history, international political economy, social anthropology, international relations, conflict studies Introduction The abstract above calls up the importance of “‘transnational’ and ‘transboundary’ theories and perspectives” and the relevance of the statement that, Worldwide, the rigid boundaries that once separated disciplines have become less circumscribed; they are no longer judged by the static conventions of yesteryear (Editorial, Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 2009: iii-iv). -

Kent Gij Dat Volk: the Anglo-Boer War and Afrikaner Identity in Postmodern Perspective

Historia 56, 2, November 2011, pp 59–72 Kent gij dat volk: The Anglo-Boer War and Afrikaner identity in postmodern perspective John Boje and Fransjohan Pretorius* Professional historians have proved resistant to the claims of postmodernism, which they see as highly theoretical, rather theatrical and decidedly threatening. As a result, the debate has become polarised, with proponents of postmodernism dismissing traditional historians as “positivist troglodytes”,1 while reconstructionist and constructionist historians speak in “historicidal” terms of deconstructionism.2 To complicate matters, postmodernism is, in the words of one of its critics, “an amorphous concept and a syncretism of different but related theories, theses and claims that have tended to be included under this one heading”,3 variously applied to art, architecture, literature, geography, philosophy and history. Yet a general perspective can be discerned in which modernism with its totalising, system-building and social- engineering focus is rejected in favour of complexity, diversity and relativity. It is held that an epochal shift took place when modernism, which prevailed from about 1850 to about 1950, lost its credibility in our fragmented, flexible, uncertain but exciting contemporary world.4 Whether or not an epochal shift of this nature can be discerned in the world at large, South Africa certainly finds itself in the throes of transition which has swept away old certainties and which challenges historians to find new ways of theorising and practising their craft. This was foreseen by the South African historian F.A. van Jaarsveld when he speculated in 1989 about a plurality of histories that would emerge in South Africa in the future.5 However, he could not move beyond the suggestion of “own” as opposed to “general” history, making use of the then fashionable categories associated with P.W. -

Legal Notices Wetlike Kennisgewings

Pr t ri 29 December 2017 Vol. 630 e 0 a, Desember No. 41361 LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER QPENBARE VERKOPE 2 No. 41361 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 29 DECEMBER 2017 CONTENTS / INHOUD LEGAL NOTICES / WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE Sales in execution • Geregtelike verkope ....................................................................................................... 11 Gauteng ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Free State / Vrystaat ....................................................................................................................... 15 KwaZulu-Natal .............................................................................................................................. 16 Western Cape / Wes-Kaap ............................................................................................................... 17 STAATSKOERANT, 29 DESEMBER 2017 No. 41361 3 4 No. 41361 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 29 DECEMBER 2017 STAATSKOERANT, 29 DESEMBER 2017 No. 41361 5 6 No. 41361 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 29 DECEMBER 2017 STAATSKOERANT, 29 DESEMBER 2017 No. 41361 7 8 No. 41361 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 29 DECEMBER 2017 STAATSKOERANT, 29 DESEMBER 2017 No. 41361 9 10 No. 41361 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 29 DECEMBER 2017 STAATSKOERANT, 29 DESEMBER 2017 No. 41361 11 SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER -

Augustus 2012 Dagsê Al Die Belangstellendes in Die Geskiedenis Van Ou Pretoria

Augustus 2012 Dagsê al die belangstellendes in die geskiedenis van ou Pretoria, Regstelling Jammer vir die fout in verlede maand se brief. ‘n Hele paar oplettende mense het dit raakgesien en my laat weet. Baie dankie. Die volgende van Prof. Andreas van Wyk: Moskou was en is nog altyd Moskou (Moskwa). Sint Petersburg, in die 17de eeu gestig deur Tsaar Pieter die Grote en ‘n duisend kilometer wes van Moskou, het wel in die 1920’s Leningrad geword en toe in die 1990’s weer Sint Petersburg (of soos sommige Suid-Afrikaners nou spot: Sint Polokwane). Nog ‘n beskrywing van Pretoria [sien ook Mei/Junie 2012 se brief] You might be interested in the following description of Pretoria written by my great great uncle, Frank Oates, in the book "Matabeleland and the Victoria Falls", edited by C.G. Oates (1881). This book is today a very valuable piece of Africana! This description was written in June 1873. "There are orange-trees with fruit on them in the gardens, and high hedges of monthly roses in flower; there are also a few large trees (blue gums), something like poplars in mode of growth, but with dark foliage. These are planted here, for the country does not seem to bear much timber naturally. Here in Pretoria are a great many English. The English keep stores; the Dutch Boers stick to farming. The latter come in with their wagons of grain, wood, and other produce, which is sold by auction at 8 a.m. in the market place. "Mielies" (unground Indian corn) fetch fifteen shillings a muid, which is about 200 pounds. -

HISTORY, STORY, NARRATIVE ECAH/EUROMEDIA 2017 July 11–12, 2017 | Brighton, UK

HISTORY, STORY, NARRATIVE ECAH/EUROMEDIA 2017 July 11–12, 2017 | Brighton, UK The European Conference on Arts & Humanities The European Conference on Media, Communication & Film Organised by The International Academic Forum “To Open Minds, To Educate Intelligence, To Inform Decisions” The International Academic Forum provides new perspectives to the thought-leaders and decision-makers of today and tomorrow by offering constructive environments for dialogue and interchange at the intersections of nation, culture, and discipline. Headquartered in Nagoya, Japan, and registered as a Non-Profit Organization 一般社( 団法人) , IAFOR is an independent think tank committed to the deeper understanding of contemporary geo-political transformation, particularly in the Asia Pacific Region. INTERNATIONAL INTERCULTURAL INTERDISCIPLINARY iafor The Executive Council of the International Advisory Board Mr Mitsumasa Aoyama Professor June Henton Professor Baden Offord Director, The Yufuku Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Dean, College of Human Sciences, Auburn University, Professor of Cultural Studies and Human Rights & Co- USA Director of the Centre for Peace and Social Justice Southern Cross University, Australia Lord Charles Bruce Professor Michael Hudson Lord Lieutenant of Fife President of The Institute for the Study of Long-Term Professor Frank S. Ravitch Chairman of the Patrons of the National Galleries of Economic Trends (ISLET) Professor of Law & Walter H. Stowers Chair in Law Scotland Distinguished Research Professor of Economics, The and Religion, Michigan State University College of Law Trustee of the Historic Scotland Foundation, UK University of Missouri, Kansas City Professor Richard Roth Professor Donald E. Hall Professor Koichi Iwabuchi Senior Associate Dean, Medill School of Journalism, Herbert J. and Ann L. Siegel Dean Professor of Media and Cultural Studies & Director of Northwestern University, Qatar Lehigh University, USA the Monash Asia Institute, Monash University, Australia Former Jackson Distinguished Professor of English Professor Monty P. -

Memories of a Lost Cause. Comparing Remembrance of the Civil War by Southerners to the Anglo-Boer War by Afrikaners

Historia, 52, 2, November 2006, pp 199-226. Memories of a Lost Cause. Comparing remembrance of the Civil War by Southerners to the Anglo-Boer War by Afrikaners Jackie Grobler* The Civil War in the United States (1861-1865) and the Anglo-Boer War in South Africa (1899-1902) hardly seem comparable. In the first place, the war in America was a civil war with no foreign power involved, while the one in South Africa was a colonial war in the sense that Britain entered the war as a colonial power with the objective of safeguarding her colonial supremacy in South Africa. In the second place, the Civil War was a much “bigger” war than the Anglo-Boer War, both in number of participants and in number of casualties suffered on both sides. The mere fact that no prominent historian has ever produced a comparative study of the two wars or even of aspects of the two wars, also places the comparability of the wars in doubt. However, there are a number of similarities between the two wars, such as the massive material, as well as psychological losses suffered by the vanquished in both wars; the intentional destruction of the territory of the vanquished carried out by the victorious side in both cases; the participation of blacks; the political issues relating to the abysmal fate of blacks in the eventual post-war dispensation in both cases; and lastly the fact that even though the South and the Boers were the losers, in both cases they managed to have their leaders and heroes such as Robert E. -

South African Film Music Representation of Racial, Cultural and National Identities, 1931-1969

South African film music Representation of racial, cultural and national identities, 1931-1969 Christopher Jeffery Town Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements forCape the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICof (COMPOSITION) in the South African College of Music UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN October 2017 University Supervisors: Assoc. Prof. Morné Bezuidenhout Assoc. Prof. Adam Haupt The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Plagiarism Declaration “This thesis/dissertation has been submitted to the Turnitin module (or equivalent similarity and originality checking software) and I confirm that my supervisor has seen my report and any concerns revealed by such have been resolved with my supervisor.” Name: Christopher Jeffery Student number: JFFCHR002 Signature: Signature Removed Date: 28 February 2017 i Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

The Mythical Boer Hero: Deconstructing Ideology and Identity in Anglo-Boer War Films

The Mythical Boer Hero: Deconstructing Ideology and Identity in Anglo-Boer War Films Anna-Marie Jansen van Vuuren, University of Johannesburg, South Africa The European Conference on Media, Communication & Film 2017 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract In this paper the author deconstructs the role of the Hero character in a sample of South African- or Anglo-Boer War1 case study films. The author argues that the Boer soldier, one of the prominent figures of White “Afrikaner” history, has been transformed into a mythical hero during the past century. The key question the author investigates is how the predominant historical myth of a community (in this case that of the White South African “Afrikaner”) influence the narratives told by its popular culture. Starting with the first South African “talkie” film, Sarie Marais, the Boer hero-archetype has been used as a vehicle for ideological messages in an attempt to construct White Afrikaner identity from an Apartheid Nationalist Party perspective. Through investigating the various archetypical guises of the Boer Hero in the films Die Kavaliers, Verraaiers, and Adventures of the Boer War the author reflects on how the various case studies’ historical contexts directly correlate with the filmmaker’s representation of the hero. Therefore, the predominant ideology or the identity that the creator subscribes to directly influences the representation of the hero figure in the story. Keywords: Afrikaner; Archetype; Anglo-Boer War; Culture; Hero; History; Identity; Ideology; Myth; Narrative; South Africa iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org 1 Worden (1998: 144) states that the term South African War is more accurate than the term “Anglo- Boer War” in reflecting “that many other South Africans were caught up in the conflict”; whilst Pretorius (2009a: ix) argues that the former term was adopted in the 1960’s by British and English- speaking South African historians that disregards the involvement of Great Britain, “the party all historians now agree had a major share in causing the war”.