The Mythical Boer Hero: Deconstructing Ideology and Identity in Anglo-Boer War Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Click Here to Download

The Project Gutenberg EBook of South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I, by J. Castell Hopkins and Murat Halstead This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I Comprising a History of South Africa and its people, including the war of 1899 and 1900 Author: J. Castell Hopkins Murat Halstead Release Date: December 1, 2012 [EBook #41521] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AFRICA AND BOER-BRITISH WAR *** Produced by Al Haines JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN, Colonial Secretary of England. PAUL KRUGER, President of the South African Republic. (Photo from Duffus Bros.) South Africa AND The Boer-British War COMPRISING A HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS PEOPLE, INCLUDING THE WAR OF 1899 AND 1900 BY J. CASTELL HOPKINS, F.S.S. Author of The Life and Works of Mr. Gladstone; Queen Victoria, Her Life and Reign; The Sword of Islam, or Annals of Turkish Power; Life and Work of Sir John Thompson. Editor of "Canada; An Encyclopedia," in six volumes. AND MURAT HALSTEAD Formerly Editor of the Cincinnati "Commercial Gazette," and the Brooklyn "Standard-Union." Author of The Story of Cuba; Life of William McKinley; The Story of the Philippines; The History of American Expansion; The History of the Spanish-American War; Our New Possessions, and The Life and Achievements of Admiral Dewey, etc., etc. -

Dissertation Terre Blanche Hj.Pdf

IDEOLOGIES AFFECTING UPPER AND MIDDLE CLASS AFRIKANER WOMEN IN JOHANNESBURG, 1948, 1949 AND 1958 by HELEN JENNIFER TERRE BLANCHE submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF A M GRUNDLINGH JOINT SUPERVISOR: DR D PRINSLOO NOVEMBER 1997 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record my thanks to my supervisor and joint supervisor who generously gave of their time and knowledge. Prof Albert Grundlingh was unfailingly helpful and patient, and Dr Dione Prinsloo kindly allowed me to make use of interviews she had conducted. Her knowledge of the Afrikaner community in Johannesburg was also invaluable. I would also like to thank my family, my husband, for his comments and proofreading, my mother for the proofreading of the final manuscript, and my children, Sara and Ruth, for their patience and tolerance. I would also like to thank my father for encouraging my interest in history from an early age. Thanks are also due to Mrs Renee d'Oiiveira, headmistress of Loreto Convent, Skinner street, for her interest in my studies and her support. 305.483936068221 TERR UNISA BI8Lf0Tt:;~:: / LIBRARY Class Klas ... Access Aanwin ... 111111111111111 0001705414 Student number: 460-005-3 I declare that "Ideologies affecting upper and middle class Afrikaner women in Johannesburg, 1948, 1949 a.nd 1958" is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references . .. ;//.-.! ~~~a.~q~~ ......... SIGNATURE DATE (H J TERRE BLANCHE) SUMMARY This thesis investigates discourses surrounding upper and middle class Afrikaner women living in Johannesburg during the years 1948, 1949 and 1958. -

The Health and Health System of South Africa: Historical Roots of Current Public Health Challenges

Series Health in South Africa 1 The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges Hoosen Coovadia, Rachel Jewkes, Peter Barron, David Sanders, Diane McIntyre The roots of a dysfunctional health system and the collision of the epidemics of communicable and non-communicable Lancet 2009; 374: 817–34 diseases in South Africa can be found in policies from periods of the country’s history, from colonial subjugation, Published Online apartheid dispossession, to the post-apartheid period. Racial and gender discrimination, the migrant labour system, August 25, 2009 the destruction of family life, vast income inequalities, and extreme violence have all formed part of South Africa’s DOI:10.1016/S0140- 6736(09)60951-X troubled past, and all have inexorably aff ected health and health services. In 1994, when apartheid ended, the health See Editorial page 757 system faced massive challenges, many of which still persist. Macroeconomic policies, fostering growth rather than See Comment pages 759 redistribution, contributed to the persistence of economic disparities between races despite a large expansion in and 760 social grants. The public health system has been transformed into an integrated, comprehensive national service, but See Perspectives page 777 failures in leadership and stewardship and weak management have led to inadequate implementation of what are This is fi rst in a Series of often good policies. Pivotal facets of primary health care are not in place and there is a substantial human resources six papers on health in crisis facing the health sector. The HIV epidemic has contributed to and accelerated these challenges. -

Book Review Article: a Selection of Some

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 33, Nr 2, 2005. doi: 10.5787/33-2-13 110 BOOK REVIEW ARTICLE: A SELECTION OF SOME SIGNIFICANT AND CONTEMPORARY PUBLICATIONS ON THE MILITARY HISTORY OF SOUTHERN AFRICA Cdr Thean Potgieter Subject Group Military History, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University Introduction The military history of South Africa and the region receives scant attention. Yet, a fascinating and multifaceted military past exists, a military history full of drama, destruction, excitement and despair. This is also a military history that tells the story of many different peoples and the struggles they waged; a history of various different military traditions; of proud warriors fighting against the odds; of changes and developments in the military sphere and of a long struggle for freedom. It is from this military history that a few significant sources will be selected for discussion in this paper. Though numerous military history books on southern Africa have been published, there are considerable shortcomings in the military historiography of the region. Many of the sources on the military history of southern Africa lack a comprehensive understanding of war in the region and of the background against which many wars have taken place. Also, though various books might address military history themes, they do not provide the didactic approach to military history the scholar and military professional requires. In addition, some of the sources are politically biased and do not necessary provide the military historian with the analytical and descriptive picture of specific conflicts, their causes, course and effects. In the last instance too little research has been done on the military history of the region as a whole. -

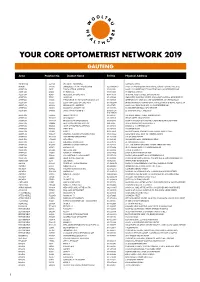

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

The Struggle for Self-Determination: a Comparative Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism Among the Quebecois and the Afrikaners

The Struggle for Self-Determination: A Comparative Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism Among the Quebecois and the Afrikaners By: Allison Down This thesis is presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Professor Simon B. Bekker Date Submitted: December, 1999 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration I, the undersigned hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not previously in its entirety or in part been submitted at any university for a degree. Signature Date Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis examines the structural factors that precipitate the emergence of ethnicity and nationalism, with a special emphasis on ethno-Iinguistic identity. Nationalist momentum leading to self-determination is also addressed. A historical comparative study of the Quebecois of Canada and the Afrikaners of South Africa is presented. The ancestors of both the Quebecois and the Afrikaners left Europe (France and the Netherlands, respectively) to establish a new colony. Having disassociated themselves from their European homeland, they each developed a new, more relevant identity for themselves, one which was also vis-a-vis the indigenous population. Both cultures were marked by a rural agrarian existence, a high degree of religiosity, and a high level of Church involvement in the state. Then both were conquered by the British and expected to conform to the English-speaking order. This double-layer of colonialism proved to be a significant contributing factor to the ethnic identity and consciousness of the Quebecois and the Afrikaners, as they perceived a threat to their language and their cultural institutions. -

19Th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence As the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Spring 5-7-2011 19th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence as the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity Kevin W. Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, Kevin W., "19th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence as the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/45 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19TH CENTURY TRAGEDY, VICTORY, AND DIVINE PROVIDENCE AS THE FOUNDATIONS OF AN AFRIKANER NATIONAL IDENTITY by KEVIN W. HUDSON Under the DireCtion of Dr. Mohammed Hassen Ali and Dr. Jared Poley ABSTRACT Apart from a sense of racial superiority, which was certainly not unique to white Cape colonists, what is clear is that at the turn of the nineteenth century, Afrikaners were a disparate group. Economically, geographically, educationally, and religiously they were by no means united. Hierarchies existed throughout all cross sections of society. There was little political consciousness and no sense of a nation. Yet by the end of the nineteenth century they had developed a distinct sense of nationalism, indeed of a volk [people; ethnicity] ordained by God. The objective of this thesis is to identify and analyze three key historical events, the emotional sentiments evoked by these nationalistic milestones, and the evolution of a unified Afrikaner identity that would ultimately be used to justify the abhorrent system of apartheid. -

Page 1 © MBAZIIRA JOEL [email protected]

© MBAZIIRA JOEL [email protected] THE ESTABLISHMENT OF BOER REPUBLICSIN SOUTH AFRICA. The Boers established independent republics in the interior of South Africa during and after the great trek. These republics included Natal, Orange Free State and later Transvaal. However, these Boer republics were annexed by the British who kept on following them even up to the interior. SUMMARY REPUBLIC YEAR OF ANNEXED BY ANNEXATION Natal/ Natalia 1843 British Orange Free State 1848 British Transvaal 1851-1877 British THE ORIGIN / FOUNDATION OF THE REPUBLICOF NATAL 1. The republic of Natal was founded by Piet Retief’s group after 1838. 2. In 1838, the Trekkers met the Zulu leader (Dingane) and tried to negotiate for land. 3. Upon the above Trekker’s request, Dingane told the Trekkers under Piet – Retief to first bring back the Zulu cattle stolen by the Tlokwa chief Sekonyela. 4. Piet-Retief tricked Sekonyela and secured the cattle from Sekonyela, Dingane became suspicious because of the quickness of Retief. 5. But still Dingane did not trust the white men, he was worried and uneasy of their arms, he clearly knew and learnt of how whites had over thrown African chiefs. 6. So, Dingane organized a beer party were he called Piet Retief and some of his sympathizers and thereafter, they were all murdered. 7. Pretorius the new Boer leader managed to revenge and defeated the Zulu at the battle of Blood ©MBAZIIRA JOEL [email protected] © MBAZIIRA JOEL [email protected] River. 8. The Boers therefore took full possession of Zulu land and captured thousands of Zulu cattle. -

334 Chapter 10 Natal Afrikaner Women and The

University of Pretoria etd – Wassermann, J M (2005) 334 CHAPTER 10 NATAL AFRIKANER WOMEN AND THE ANGLO-BOER WAR The role and plight of the Republican Afrikaner women have always formed an integral, and sometimes even central part of the historiography of the Anglo-Boer War. The emphasis in the large number of academic and popular works and published memoirs invariably falls on the suffering of Afrikaner women and children in the concentration camps. Despite this volume of work, Helen Bradford1 maintains that one of the seminal questions faced by the historiography of the Anglo-Boer War is the neglect of the unique war experiences of women. One group previously neglected was Natal Afrikaner women who formed a stratified and diverse group. Some, like MJ Zietsman of Snelster near Estcourt, whose daughter, the widow Wallace had been to England and who kept thoroughbred Pointers, were wealthy and sophisticated.2 Another, like ME Kock, read Tennyson and Shakespeare,3 while Emily Pieters owned 20 bound music books for playing the piano and harmonium.4 On the other end of the social scale were women like Annie Katrina Slabbert of Dundee who sewed and took in laundry to survive.5 These class differences were underpinned by the patriarchal system in which the women functioned. Married women had the least power and received little support or recognition from the authorities. In contrast widows wielded much more economic and political power and were also able to generate letters and other documents.6 However, regardless of their educational, social, economic or marital status, most Natal Afrikaner women suffered, in one way or another, during the war. -

South Africa and Russia (1890–2010)

Viewing ‘the other’ over a hundred and a score more years: South Africa and Russia (1890–2010) I LIEBENBERG* Abstract Whether novel is history or history is novel, is a tantalising point. “The novel is no longer a work, a thing to make last, to connect the past with the future but (only) one current event among many, a gesture with no tomorrow” Kundera (1988:19). One does not have to agree with Kundera to find that social sciences, as historiography holds a story, a human narrative to be shared when focused on a case or cases. In this case, relations between peoples over more than a century are discussed. At the same time, what is known as broader casing in qualitative studies enters the picture. The relations between the governments and the peoples of South Africa and Russia (including the Soviet Union), sometimes in conflict or peace and sometimes at variance are discussed. Past and present communalities and differences between two national entities within a changing international or global context deserve attention while moments of auto-ethnography compliment the study. References are made to the international political economy in the context of the relations between these countries. Keywords: Soviet Union, South Africa, Total Onslaught, United Party, Friends of the Soviet Union, ideological conflict (South Africa), Russians (and the Anglo-Boer War), racial capitalism, apartheid, communism/Trotskyism (in South Africa), broader casing (qualitative research) Subject fields: political science, sociology, (military) history, international political economy, social anthropology, international relations, conflict studies Introduction The abstract above calls up the importance of “‘transnational’ and ‘transboundary’ theories and perspectives” and the relevance of the statement that, Worldwide, the rigid boundaries that once separated disciplines have become less circumscribed; they are no longer judged by the static conventions of yesteryear (Editorial, Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 2009: iii-iv). -

SOUTH AFRICA and the TRANSVAAL WAR South Africa and the Transvaal War

ERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO 3 1822 01546 6535 / ^ HTKFRIQ AND THE SOUTH AFRICA AND THE TRANSVAAL WAR South Africa AND THE Transvaal War BY LOUIS CB.ESWICKE AUTHOR OF " ROXANE," ETC. WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS IN SIX VOLUMES VOL. I—FROM THE FOUNDATION OP CAPE COLONY TO THE BOER ULTIMATUM OF QTH OCT. 1899 EDINBURGH : T. C. <Sf E. C. JACK 19C0 PREFATORY NOTE In writing this volume my aim has been to present an unvar- nished tale of the circumstances—extending over nearly half a century—which have brought about the present crisis in South Africa. Consequently, it has been necessary to collate the opinions of the best authorities on the subject. My acknowledgments are due to the distinguished authors herein quoted for much valuable information, throwing light on the complications that have been accumulating so long, and that owe their origin to political blundering and cosmopolitan scheming rather than to the racial antagonism between Briton and Boer. L. C. CONTENTS—Vol. I. PAGE CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE ix INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I FAriE The Growth of the Transvaal. 13 Some Domestic Traits 18 The Boer Character . 15 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS—Vol. I. I. COLOURED PLATES Dying to Save the Qiken's Drum-Major and Drummer, Cold- Colours. An Incident of the Battle stream Guards .... 80 of Isandlwana. By C. E. Fripp Colour -Sergeant and Private, /• rontispiece THE Scots Guards . .104 Colonel of the ioth Hussars Sergeant AND Bugler, ist Argyle (H.R.H. the Prince ov Wales). i6 AND Sutherland Highlanders . 140 2ND Dr.^goons CRoval ScotsGreys) 32 Colour-Skrgeant and Private (in Regiment) .