Maximizing #Metoo: Intersectionality & the Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atom Smashersrel

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit itvs.org/pressroom/photos/ For the program companion website, visit pbs.org/independentlens/atomsmashers “THE ATOM SMASHERS,” AN EXCITING INSIDE LOOK AT THE FRONTIER OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH, TO HAVE ITS BROADCAST PREMIERE ON THE EMMY ® AWARD–WINNING PBS SERIES INDEPENDENT LENS ON TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 25, AT 10 PM “Finding this Higgs particle will help scientists figure out why the universe is made of something instead of nothing, why there are atoms, people, planets, stars and galaxies. But it also will do much more than that. It will open a door to a hidden world of physics, where scientists hope to find unimagined wonders that will make relativity and quantum mechanics seem like Tinker Toys.” —Ronald Kotulak, Chicago Tribune (San Francisco, CA)—Physicists at Fermilab, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator laboratory, are closing in on one of the universe’s best-kept secrets, the Holy Grail of physics: why everything has mass. With the Tevatron, an underground particle accelerator buried deep beneath the Illinois prairie, Fermilab scientists smash matter together, accelerating protons and antiprotons in a four-mile-long ring at nearly the speed of light, to find a particle—the Higgs boson—whose existence was theorized nearly 40 years ago by Scottish scientist Peter Higgs. The physicists searching for the Higgs boson are excited; they may be approaching the discovery of a lifetime, and there’s almost certainly a Nobel Prize for whoever finally finds it. -

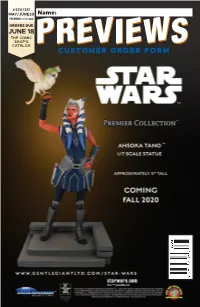

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: -

BOMBSHELL: the Hedy Lamarr Story

! BOMBSHELL: The Hedy Lamarr Story ! Directed by Alexandra Dean ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! **Official Selection – 2017 Tribeca Film Festival, WINNER “Best of Fest” Nanctucket, WINNER San Francisco! Jewish Fest AUDIENCE AWARD** ! ! ! ! DISTRIBUTOR CONTACT SALES CONTACT Emily Russo David Koh, Submarine Entertainment 212-274 1989 [email protected] [email protected] ! ! ! ! 89 min // USA // 2017 http://www.reframedpictures.com/bombshell/ SYNOPSIS Hollywood star Hedy Lamarr (ZIEGFELD GIRL, SAMSON AND DELILAH) was known as the world's most beautiful woman – Snow White and Cat Woman were both based on her iconic look. However, her arresting looks and glamorous life stood in the way of her being given the credit she deserved as an ingenious inventor whose pioneering work helped revolutionize modern communication. Mislabeled as “just another pretty face,” Hedy’s true legacy is that of a technological trailblazer. She was an Austrian Jewish emigre who invented a covert communication system to try and help defeat the Nazis, then gave her patent to the Navy, but was ignored and told to sell kisses for war bonds instead. It was only towards the very end of her life that tech pioneers discovered her concept which is now used as the basis for secure WiFi, GPS and Bluetooth. Hedy never publicly talked about her life as an inventor and so her family thought her story died when she did. But in 2016, director Alexandra Dean and producer Adam Haggiag unearthed four never-before-heard audio tapes of Hedy speaking on the record about her incredible life. Combining this newly discovered interview with intimate reflections from her children, closest friends, family and admirers, including Mel Brooks and Robert Osborne, BOMBSHELL (executive produced by Susan Sarandon, Michael Kantor and Regina Scully) finally gives Hedy Lamarr the chance to tell her own story. -

Bull8-Cover Copy

220 COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN More New Evidence On THE COLD WAR IN ASIA Editor’s Note: “New Evidence on History Department (particularly Prof. Zhang Shuguang (University of Mary- the Cold War in Asia” was not only the Priscilla Roberts and Prof. Thomas land/College Park) played a vital liai- theme of the previous issue of the Cold Stanley) during a visit by CWIHP’s di- son role between CWIHP and the Chi- War International History Project Bul- rector to Hong Kong and to Beijing, nese scholars. The grueling regime of letin (Issue 6-7, Winter 1995/1996, 294 where the Institute of American Studies panel discussions and debates (see pro- pages), but of a major international (IAS) of the Chinese Academy of Social gram below) was eased by an evening conference organized by CWIHP and Sciences (CASS) agreed to help coor- boat trip to the island of Lantau for a hosted by the History Department of dinate the participation of Chinese seafood dinner; and a reception hosted Hong Kong University (HKU) on 9-12 scholars (also joining the CWIHP del- by HKU at which CWIHP donated to January 1996. Both the Bulletin and egation were Prof. David Wolff, then of the University a complete set of the the conference presented and analyzed Princeton University, and Dr. Odd Arne roughly 1500 pages of documents on the newly available archival materials and Westad, Director of Research, Norwe- Korean War it had obtained (with the other primary sources from Russia, gian Nobel Institute). Materials for the help of the Center for Korean Research China, Eastern Europe and other loca- Bulletin and papers for the conference at Columbia University) from the Rus- tions in the former communist bloc on were concurrently sought and gathered sian Presidential Archives. -

The Little Steel Strike of 1937

This dissertation has been Mic 61-2851 microfilmed exactly as received SOFCHALK, Donald Gene. THE LITTLE STEEL STRIKE OF 1937. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 History, modem ; n University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE LITTLE STEEL STRIKE OF 1937 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Donald Gene Sofchalk, B. A., M. A. ***** The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of History PREFACE On Sunday, May 30, 1937, a crowd of strikers and sympathizers marched toward the South Chicago plant of the Republic Steel Corpora tion. The strikers came abreast a line of two hundred Chicago police, a scuffle ensued, and the police opened fire with tear gas and revolvers. Within minutes, ten people were dead or critically injured and scores wounded. This sanguinary incident, which came to be known as the "Memorial Day Massacre," grew out of a strike called by the Steel Workers Or&soizing Committee of the CIO against the so-called Little Steel companies. Two months previously the U. S. Steel Corporation, traditional "citadel of the open shop," had come to terms with SWOC, but several independent steel firms had refused to recognize the new union. Nego tiations, never really under way, had broken down, and SWOC had issued a strike call affecting about eighty thousand workers in the plants of Republic, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company, and Inland Steel Company in six states. The Memorial Day clash, occurring only a few days after the * strike began, epitomized and undoubtedly intensified the atmosphere of mutual hostility which characterized the strike. -

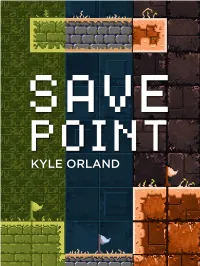

Reporting from a Video Game Industry in Transition, 2003 – 2011

Save Point Reporting from a video game industry in transition, 2003 – 2011 Kyle Orland Carnegie Mellon University: ETC Press Pittsburgh, PA Save Point: Reporting from a video game industry in transition, 2003— 2011 by Carnegie Mellon University: ETC Press is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Copyright by ETC Press 2021 http://press.etc.cmu.edu/ ISBN: 9-781304-268426 (eBook) TEXT: The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NonDerivative 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/) IMAGES: The images of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NonDerivative 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/) Table of Contents Introduction COMMUNITY Infinite Princesses WebGame 2.0 @TopHatProfessor Layton and the Curious Twitter Accounts Madden in the Mist Pinball Wizards: A Visual Tour of the Pinball World Championships A Zombie of a Chance: LooKing BacK at the Left 4 Dead 2 Boycott The MaKing (and UnmaKing) of a Nintendo Fanboy Alone in the StreetPass Crowd CRAFT Steel Battalion and the Future of Direct-InVolVement Games A Horse of a Different Color Sympathy for the DeVil The Slow Death of the Game OVer The Game at the End of the Bar The World in a Chain Chomp Retro-Colored Glasses Do ArKham City’s Language Critics HaVe A Right To 'Bitch'? COMMERCE Hard DriVin’, Hard Bargainin’: InVestigating Midway’s ‘Ghost Racer’ Patent Indie Game Store Holiday Rush What If? MaKing a “Bundle” off of Indie Gaming Portal Goes Potato: How ValVe And Indie DeVs Built a Meta-Game Around Portal 2’s Launch Introduction As I write this introduction in 2021, we’re just about a year away from the 50th anniVersary of Pong, the first commercially successful video game and probably the simplest point to mark the start of what we now consider “the video game industry.” That makes video games one of the newest distinct artistic mediums out there, but not exactly new anymore. -

Beyond Blonde: Creating a Non-Stereotypical Audrey in Ken Ludwig's Leading Ladies

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 Beyond Blonde: Creating A Non-stereotypical Audrey In Ken Ludwig's Leading Ladies Christine Young University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Young, Christine, "Beyond Blonde: Creating A Non-stereotypical Audrey In Ken Ludwig's Leading Ladies" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4155. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4155 BEYOND BLONDE: CREATING A NON-STEREOTYPICAL AUDREY IN KEN LUDWIG’S LEADING LADIES by CHRISTINE MARGARET YOUNG B.F.A. Northern Kentucky University, 1998 M.A. University of Kentucky, 2008 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2009 © 2009 Christine M. Young ii ABSTRACT BEYOND BLONDE: CREATING A NON-STEREOTYPICAL AUDREY IN KEN LUDWIG’S LEADING LADIES To fulfill the MFA thesis requirements, I have the opportunity to play Audrey in Ken Ludwig’s Leading Ladies as part of the 2008 UCF SummerStage season. Leading Ladies is a two act farce dealing with the shenanigans of two men, Jack and Leo, who impersonate Florence Snider’s long lost nieces in order to gain her fortune. -

"Nostalgia" Magazine Exterior in Flight Various Pictures in "Sea Wings" (Book) Various Pictures in "Wings to the Orient" (Book) Many Pictures in "Airpower" Magazine

List of research materials for Night over water A: The plane Theoretical take-off and landing pattern Operation manual Maintenance manual Supplementary manual which mentions revolver but no details Testing & service history of B-314 Sturctural details of B-314 Extracts from manuals General history of the B-314 Specifications Servicing the 314 Design & Development of the 314 Technical specifications 314s in war service 1981 Water Flying Annual: good technical article on flying the 314 NY Times clipping 19 Mar 1939 Pictures: Front view Cutaway-l Cutaway-2 Cutaway-3 Fuelling the right-hand hydrostabiliser Various pictures in "Nostalgia" magazine Exterior in flight Various pictures in "Sea Wings" (book) Various pictures in "Wings to the Orient" (book) Many pictures in "Airpower" magazine B: The crew Training of B-314 crew Flight log Timetable Baltimore to Horta Baltimore to Horta-2 Pan Am schedules Take-off and landing from the test pilot's PoV Technical article on crew, routes and especially radio Reminiscences of a navigator Detailed description of flight deck Pan Am Systems Operations Manual NY Times clippings 4 June to 29 June 1939: First flight Time zones in Botwood and Shediac "Flying the Oceans": Explanation of critical wave height p123 Problems of navigating the Atlantic p136 Landing at Foynes p128-9 Notes: Take-off Schedule Pan Am flight 101 Crew Flying the Atlantic Miscellaneous Pictures: Flight deck--1 Flight deck--2 Flight deck--3 Flight deck--4 Flight deck--5 Flight deck--6 Engineer's station C: The passengers Everyday life--UK -

ECP 19-20 Brochure Updated ECP 19-20.Qxd

EISEMANN CENTER PRESENTS 2019-2020 SEASON EXTRAORDINARY, EXCEPTIONAL & INSPIRING! Photo of Mandy Patinkin by Joan Marcus FROM THE MANAGING DIRECTOR EXTRAORDINARY, EXCEPTIONAL & INSPIRING... We are pleased to present to you another season of outstanding nationally touring artists and attractions. The 2019-2020 season of Eisemann Center Presents represents our 17th year of pre- senting quality and diverse programming for the City of Richardson and North Texas commu- nities we serve. We have 24 shows and one very special event we feel you will find to be Extraordinary, Exceptional & Inspiring! This season features shows returning by popular demand mixed with a variety of new artists and productions we have discovered and wish to share with you on the stages of the Eisemann Center. Some new Extraordinary shows, presented for your enjoyment, include Lee Rocker of the Stray Cats (Oct. 26); An Evening with Renée Elise Goldsberry, Tony Award winner from the original cast of Hamilton (Nov. 2); and Oscar-nominated and Emmy Award-winning actor Renée Taylor in her new autobiographical solo show My Life On A Diet (Feb. 14- 16). Featured returning artists our audiences found to be Exceptional include Riders In The Sky with The Quebe Sisters in Christmas The Cowboy Way (Dec. 17); our good friend Mandy Patinkin in his new concert Diaries (Jan. 17); and Asleep At The Wheel’s 50th Anniversary Tour (Mar. 28). On the Inspiring side of programming we have Mandy Harvey, deaf American singer-songwriter and finalist on America’s Got Talent returning with her band for a full week of educational resi- dency and performance with students at UT Dallas (Feb. -

Broadway Flops, Broadway Money, and Musical Theater Historiography

arts Article How to Dismantle a [Theatric] Bomb: Broadway Flops, Broadway Money, and Musical Theater Historiography Elizabeth L. Wollman The Department of Fine and Performing Arts, Baruch College, The City University of New York (CUNY), New York, NY 10010, USA; [email protected] Received: 7 May 2020; Accepted: 26 May 2020; Published: 29 May 2020 Abstract: The Broadway musical, balancing as it does artistic expression and commerce, is regularly said to reflect its sociocultural surroundings. Its historiography, however, tends for the most part to emphasize art over commerce, and exceptional productions over all else. Broadway histories tend to prioritize the most artistically valued musicals; occasional lip service, too, is paid to extraordinary commercial successes on the one hand, and lesser productions by creators who are collectively deemed great artists on the other. However, such a historiography provides less a reflection of reality than an idealized and thus somewhat warped portrait of the ways the commercial theater, its gatekeepers, and its chroniclers prioritize certain works and artists over others. Using as examples Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death (1971), Merrily We Roll Along (1981), Carrie (1988), and Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark (2011), I will suggest that a money-minded approach to the study of musicals may help paint a clearer picture of what kinds of shows have been collectively deemed successful enough to remember, and what gets dismissed as worthy of forgetting. Keywords: Broadway musicals; Broadway flops; commercial theater industry; Carrie; Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark; Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death; Merrily We Roll Along; theater economics 1. -

Bombshell Ebrochure V7 Previ

Conceived as a celebration of craftsmanship and couturier confectionaries, Bombshell is a collection of uniquely designed patisserie masterpieces handcrafted with 3D elements by a team of talented pastry artists to create unforgettably fun-filled yet explosively delicious experiences for like-minded trendsetters. your very own Bombshell and create the greatest hit? Find out from our smashing tips. Dress to impress! DUH! Get your weapon ready & The more, the merrier! crack the chocolate shell! Do use more than one cam for both video and pics :) Hit it sideway or from the Share the sweet stash! Sharing is caring. top? Either way! Just keep Don’t forget to use the gift Don’t forget to post on calm & smash on! bags in the box so your Bombshell.hkg guests can take the love Bombshell_hkg and joy back home! Each Bombshell comes along with a vanity stick, 10 meticulously designed Bomb Packets and a serving tray. WARNING Ingredients M&M, Malteser, Chocolate bonbon, Yoghurt Coated Apricot, With every Bombshell being made-to-order, you are recommended to enjoy it at its Mini Oreo, Mini Chocolate Cupcake, Mini Blueberry Cupcake, best on the delivery date! Blisters Cake, Chocolate Brownies, Jelly Beans, Marshmallow, However, if you would like to save the surprise for someone special – please follow the Meringue, Madeleine, Almond Biscuit, Coffee Cookies and below storage instruction and warm reminders to keep the Bomb cool till after school:- Candies. Ingredients may be subject to change based on design and flavours of products. Please let us know if you are allergic to any of these items Smashing it on the same day? Keep it at room temperature for up to 3 hours. -

“Broadway & Musicals” Showcase

“Broadway & Musicals” Showcase “Astaire Dancing: The Musical Films” by John Mueller (1985, HC/DJ). Minimum Bid: $4 With a dancing career that spanned half a century, Fred Astaire displayed unparalleled brilliance, beauty and timeless artistry. To better understand Astaire’s unique choreographic style, this book examines in detail each of the dance scenes of his 31 filmed musicals, Astaire’s personality & working methods, and his numerous contributions to filmed dance. “Glamorous Musicals: Fifty Years of Hollywood’s Ultimate Fantasy” by Ronald Bergen, Foreword by Ginger Rogers (1984, HC/DJ). Minimum Bid: $3 Gorgeous actors, leggy chorus girls, superb dancers & musicians, lavish costumes and sets—all are described with style, wit and perception in this generously illustrated book. Discover the artistry of the stars, and the mastery of the directors & designers, of over 100 Hollywood musicals. CD: “My Fair Lady” With Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews (Digitally Mastered CD of Original 1959 London Recording). Minimum Bid: $2 One of the greatest musical theater shows ever created, My Fair Lady is a charming adaptation of George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion, pitting flower girl Eliza Doolittle (Julie Andrews) against Prof. Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison), the self-absorbed and ill-tempered linguist who bets that he can turn her into a lady by improving her diction. This classic recording includes popular songs such as: "Wouldn't It Be Loverly," "The Rain in Spain," "I Could Have Danced All Night," "On the Street Where You Live," and "Get Me to the Church on Time." Vintage Souvenir Program and Winter Garden Playbill for “Michael Todd’s Peep Show” (1950, SC).