Mozambique Malaria Operational Plan FY 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eu Leio Agreement No. AID-656-A-14-00011

ATTACHMENT 3 Final Report Name of the Project: Eu Leio Agreement No. AID-656 -A-14-00011 FY2016: 5th Year of the Project EU LEIO Final Report th Date of Submission: October 20 , 2017 1 | P a g e Project Duration: 5 years (October 1st, 2014 to December 31th, 2019) Starting Date: October 1st 2014 Life of project funding: $4,372,476.73 Geographic Focus: Nampula (Mogovolas, Meconta, Rapale) and Zambézia (Alto Molocué, Maganja da Costa, Mopeia and Morrumbala) Program/Project Objectives (over the life of the project) Please include overview of the goals and objectives of the project (½-1 page). Goal of the project: Contribute to strengthen community engagement in education in 4 districts of Zambézia and 3 of Nampula province to hold school personnel accountable for delivering quality education services, especially as it relates to improving early grade reading outcomes. Objectives of the project: ❖ Improve quantity and quality of reading instruction, by improving local capacity for writing stories and access to educational and reading materials in 7 districts of Nampula and Zambezia provinces and; ❖ Increase community participation in school governance in 7 districts of Nampula and Zambezia provinces to hold education personnel accountable to delivering services, reduce teacher tardiness and absenteeism and the loss of instructional time in target schools. Summary of the reporting period (max 1 page). Please describe main activities and achievements of the reporting period grouped by objective/IR, as structured to in the monitoring plan or work plan. Explain any successes, failures, challenges, major changes in the operating environment, project staff management, etc. The project Eu leio was implemented from October 2014 to December 2019. -

Projectos De Energias Renováveis Recursos Hídrico E Solar

FUNDO DE ENERGIA Energia para todos para Energia CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFÓLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES Edition nd 2 2ª Edição July 2019 Julho de 2019 DO POVO DOS ESTADOS UNIDOS NM ISO 9001:2008 FUNDO DE ENERGIA CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFOLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES FICHA TÉCNICA COLOPHON Título Title Carteira de Projectos de Energias Renováveis - Recurso Renewable Energy Projects Portfolio - Hydro and Solar Hídrico e Solar Resources Redação Drafting Divisão de Estudos e Planificação Studies and Planning Division Coordenação Coordination Edson Uamusse Edson Uamusse Revisão Revision Filipe Mondlane Filipe Mondlane Impressão Printing Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Tiragem Print run 300 Exemplares 300 Copies Propriedade Property FUNAE – Fundo de Energia FUNAE – Energy Fund Publicação Publication 2ª Edição 2nd Edition Julho de 2019 July 2019 CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE RENEWABLE ENERGY ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS PROJECTS PORTFOLIO RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES PREFÁCIO PREFACE O acesso universal a energia em 2030 será uma realidade no País, Universal access to energy by 2030 will be reality in this country, mercê do “Programa Nacional de Energia para Todos” lançado por thanks to the “National Energy for All Program” launched by Sua Excia Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, Presidente da República de Moçam- His Excellency Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, President of the -

Environmental and Social Management Framework (Esmf)

E4142 REPÚBLICA DE MOÇAMBIQUE Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTÉRIO DA PLANIFICAÇÃO E DESENVOLVIMENTO DIRECÇÃO NACIONAL DE SERVIÇOS DE PLANEAMENTO Public Disclosure Authorized Mozambique Integrated Growth Poles Project (P127303) ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Draft Final Public Disclosure Authorized Maputo, February 2013 0 LIST OF ACRONYMS ANE National Roads Administration CBNRM Community-Based Natural Resource Management DA District Administration DCC District Consultative Council DNA National Directorate for Water DNE National Directorate for Energy DNPO National Directorate for Planning DNAPOT National Directorate for Land Planning DNPA National Directorate for Environmental Promotion and Education DPA Provincial Directorate of Agriculture DPCA Provincial Directorate for the Coordination of Environmental Affairs DPOPH Provincial Directorate of Public Works and Housing EA Environmental Assessment EDM Electricidade de Moçambique EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FIPAG Water Supply Investment and Asset Management Fund GAZEDA Special Economic Zones Office GDP Gross Domestic Product GOM Government of Mozambique IDA International Development Association IDCF Innovation and Demonstration Catalytic Fun MAE Ministry of State Administration MCA Millennium Challenge Account MCC -

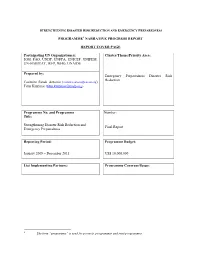

Programme1 Narrative Progress Report Report

STRENGTHENING DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS PROGRAMME1 NARRATIVE PROGRESS REPORT REPORT COVER PAGE Participating UN Organization(s): Cluster/Theme/Priority Area: IOM, FAO, UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, UNIFEM, UN-HABITAT, WFP, WHO, UNAIDS Prepared by: Emergency Preparedness Disaster Risk Reduction Casimiro Sande Antonio ([email protected]) Titus Kuuyuor ([email protected]) Programme No. and Programme Report Number: Title: Strengthening Disaster Risk Reduction and Final Report Emergency Preparedness Reporting Period: Programme Budget: January 2008 – December 2011 US$ 10,000,000 List Implementing Partners: Programme Coverage/Scope: 1 The term “programme” is used for projects, programmes and joint programmes. Acronyms: Programme Duration/Closed Programme: CENOE - National Emergency Operations Centre 2008-2011 (extended to 2011) COE – Emergency Operations Centre CPFA- Centro Provincial de Formação Agraria (provincial centre for agrarian training) CTGC - Conselho Técnico de Gestão das Calamidades (technical council for disaster management) DARIDAS- Directorate for Arid and Semi Arid Zones (INGC) DNA- National Directorate for Waters DPOPH – Provincial directorates for Public Works and Housing DRM - Disaster Risk Management DRR - Disaster Risk Reduction DRR&EP – Disaster Risk Reduction and Emergency Preparedness ECHO _ European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil protection EWS - Early Warning System GRIP – Global Risk Identification Programme HCTWG – Humanitarian Country Team Working Group HFA - Hyogo Framework -

Mozambique Environmental Threats and Opportunities Report 2002

Report submitted to the United States Agency for International Development Environmental Mozambique Threats and Opportunities Under the BioFor Indefinite Quantity Contract (IQC), Contract No. LAG-I-00-99-00013-00 , Task Order No. 808 December 2002 Presented to: USAID/Mozambique Presented by: ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Suite 300 Burlington, Vermont 05401 USA Tel: (802) 658-3890 Fax: (802) 658-4247 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements Mozambique is a large and complex country, and the team conducting this assessment of environmental threats and opportunities relied heavily on many other people for information and insights. We thank all of the staff of USAID/Mozambique who assisted us, but especially David Stephens, the Mission Environmental Officer. He was instrumental in our work, from drafting a challenging but clear scope of work to helping with logistical arrangements while the team was working in Mozambique. Scott Simons, the Mission’s Agricultural Policy Advisor, also assisted us greatly. We met with more than 60 people in Mozambique, and each of them contributed important information to our effort. Jennifer d’Amico of WWF-US provided the map of the potential natural vegetation of Mozambique, for which we are grateful. We hope this assessment will contribute to the USAID’s support for environmentally sustainable economic development in Mozambique and the conservation of its rich biological diversity. ETOA for USAID/Mozambique i Table of Contents Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... -

Emergency Appeal Operations Update Mozambique: Floods

Emergency Appeal Operations Update Mozambique: Floods Emergency appeal n° MDRMZ011 Six Month Operations Update Timeframe covered by this update: 21 January – 21 June 2015 Emergency Appeal operation start date: Timeframe: Nine months (End date: 21 October 2015) 21 January 2015 Appeal budget: Appeal coverage: Total estimated Red Cross and Red Crescent CHF 1,095,475 92% response to date: CHF 1,003,154 (in cash and kind) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) allocated: CHF 120,000 N° of people being assisted: 17,620 people (3,524 households) Host National Society presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): 300 volunteers, 18 NDRT staff members, Zambézia Provincial Branch and 10 CVM staff members at the Headquarters. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: Spanish Red Cross and Danish Red Cross Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: National Disaster Management Institute (INGC), UN-Habitat, IOM, World Health Organisation, UNICEF, Ministry of Health, COSACA, (CONCERN, CARE, Save the Children) KUKUMI, ADRA, WFP, World Vision International and other stakeholders. Appeal history From late November 2014 to January 2015: period of heavy rainfall 12 January 2015: Council of Ministers declared the institutional red alert for the Central and Northern provinces. 15 January 2015: Mozambique Red Cross (CVM) deploys National Disaster Response Team (NDRT) members to Zambézia and Nampula provinces. 21 January 2015: CHF 120,000 DREF allocated as start-up funds for the appeal operation. 21 January 2015: Emergency Appeal launched for CHF 846,755 10 February 2015: Operations Update n°1 issued to provide progress of the operations to date. -

Mapping Animal Traction Suitability in Rural Mozambique

April 2016 • Research Paper 79E Exploiting the potential for expanding cropped area using animal traction in the smallholder sector in Mozambique Benedito Cunguara David Mather Tom Walker Bordalo Mouzinho Jaquelino Massingue Rafael Uaiene Benedito Cunguara and David Mather are research associate and assistant professor, respectively, Michigan State University; Tom Walker is an independent researcher; Bordalo Mouzinho is a graduate student at the University of Tokyo; Jaquelino Massingue and Rafael Uaiene are research analyst and assistant professor, respectively, Michigan State University. DIRECTORATE OF PLANNING AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION Research Paper Series The Directorate of Planning and International Cooperation of the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security maintains two publication series for research on food security issues. Publications under the Flash series are short (3-4 pages), carefully focused reports designated to provide timely research results on issues of great interest. Publications under the Research Paper series are designed to provide longer, more in-depth treatment of food security issues. The preparation of Flash and Research Papers, and their discussion with those who design and influence programs and policies in Mozambique, is an important step in the Directorate’s overall analyses and planning mission. Comments and suggestion from interested users on reports under each of these series help identify additional questions for consideration in later data analyses and report writing, and in the design of further research activities. Users of these reports are encouraged to submit comments and inform us of ongoing information and analysis needs. Raimundo Matule National Director Directorate of Planning and International Cooperation Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Recommended citation: Cunguara, B., Mather, D., Walker, T., Mouzinho, B, Massingue, J., and Uaiene, R., 2016. -

T Go to the Communal Villages!' Peasants and the Policy of '

‘They can kill us but we won’t go to the communal villages!’ Peasants and the Policy of ‘Socialisation of the Countryside’ in Zambezia SÉRGIO CHICHAVA Lecturer, Eduardo Mondlane University Institute of Economic and Social Studies (IESE), Maputo Translated by Benjamin Legg, Brown University After its ascent to power in June 1975, the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (Frelimo) adopted socialism as a model for development. This led to the implementa- tion of many policies, one of which was the ‘socialisation and modernisation of the countryside’. More concretely, it involved the implantation of communal villages, collective machambas [farm, plot] cooperatives, the prohibition of initiation rites and the abolition of traditional authorities. In the province of Zambezia Frelimo faced innumerable obstacles to putting the policy of ‘socialisation of the countryside’ into practice. This happened to such a degree that, according to the government of Zambezia in that era, the population of other provinces like Nampula, where this policy was more highly prioritised, fled to Zambezia because they knew that there were no communal villages. The objective of this article is to analyse the ‘socialisation of the countryside’ campaign in Zambezia and the different forms of resistance to this policy on the part of the Zambezian peasants.1 After its ascent to power in June 1975, the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (Frelimo) adopted socialism as a model for development. This led to the implemen- tation of many policies, among which was the ‘socialisation -

Evaluation of Sida Financed Interventions for Increased Access to Electricity for Poor People

Evaluation of Sida financed interventions for Evaluation of Sida financed interventions for increased access to Electricity for poor people 2014:1 Sida Evaluation increased access to Electricity for poor people This report evaluates the contribution Sweden has made to development and poverty Dolf Noppen reduction in Vietnam from the inception of the development co-operation program in 1967 to 2011. The evaluation draws five main conclusions: (i) Sweden responded to important multidimensional development needs in Vietnam. (ii) There is mixed evidence of effective and efficient delivery of Swedish development co-operation in Vietnam. (iii) There is clear evidence that the Swedish development co-operation nurtured an environ- Evaluation of Sida financed ment in Vietnam that assisted in providing the pre-conditions for sustained poverty reduction. (iv) The evaluation points to three key lessons learned for future development interventions for increased access co-operation. (v) The evaluation concludes that Swedish development co-operation with Vietnam has had strong poverty reducing impacts. This report is one of three reports commissioned by Sida to evaluate countries in Asia to Electricity for poor people (also Laos and Sri Lanka) where Swedish development co-operation is being, or has been, phased out. It is complemented by a synthesis report. Drawing on international experience and case studies in Tanzania and Mozambique Sida EVALUATION 2014:1 SWEDISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AGENCY Address: SE-105 25 Stockholm, Sweden. Visiting address: Valhallavägen 199. Phone: +46 (0)8-698 50 00. Fax: +46 (0)8-20 88 64. www.sida.se [email protected] Sida Evaluation 2014:1 Evaluation of Sida financed interventions for increased access to Electricity for poor people DRAWING ON INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE AND CASE STUDIES IN TANZANIA AND MOZAMBIQUE Synthesis Report Dolf Noppen Author: Dolf Noppen. -

Review Team Beatrice Okeyo Hung Ha Nguyen Marla Dava Peter Schleischer Stefan Islandi Paulo Matusse

Review team Beatrice Okeyo Hung Ha Nguyen Marla Dava Peter Schleischer Stefan Islandi Paulo Matusse 1 | P a g e The Final Evaluation of MDRMZ011 was commissioned by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Southern Africa regional representation and Mozambique Red Cross Society (CVM). It was carried out from 19-26 October 2015 in Zambezia province in Mopeia (Mudiba and 1 de Mai0) and Mocuba (Nacogolone and Macuvine). Author: Beatrice Okeyo Photos: IFRC Acknowledgements On behalf of the authors, Mozambique Red Cross Society and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) would like to thank all those that made this exercise possible, with gratitude extended to the people that participated, the volunteers and translators who assisted. Our appreciation also goes to the Ministry of Public Housing and National Disaster Management Institute (INGC) in Quelimane for their participation and cooperation during this operation in general and this evaluation in particular. Their inputs into this exercise have been valuable. 2 | P a g e Cover photo: Focus Group Discussion in 1 de Maio during the evaluation. IFRC© 2015 Table of contents: Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive summary: ................................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 1: Background .......................................................................................................................... -

Conspicuous Destruction

CONSPICUOUS DESTRUCTION War, Famine and the Reform Process in Mozambique An Africa Watch Report Human Rights Watch New York !!! Washington !!! Los Angeles !!! London ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The bulk of the research and writing for this report was done by Karl Maier, a consultant to Africa Watch, during 1990B91. Additional material provided was by Kemal Mustafa, Africa Watch researcher, in 1991, and Alex Vines, Africa Watch consultant, in 1992. Ben Penglase, Africa Watch associate wrote the chapter on U.S. policy. The report was edited by Alex de Waal, Associate Director of Africa Watch. Africa Watch would like to thank the Mozambique government for extending an invitation to visit Mozambique and for facilitating the research upon which this report is based. We would also like to thank the many Mozambicans who have contributed their experiences to the report. Africa Watch is grateful to the J. Roderick MacArthur Foundation for a grant in support of its research on human rights in Mozambique. Copyright 8 July 1992 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalogue Card No.: 92-73261 ISBN 1-56432-079-0 Cover design by Deborah Thomas. Africa Watch Africa Watch was established in May 1988 to monitor and promote observance of internationally recognized human rights in Africa. The chair of Africa Watch is William Carmichael. Alice Brown is the vice chair. Rakiya Omaar, is the executive director. Alex deWaal is associate director. Janet Fleischman and Karen Sorensen are research associates. Barbara Baker, Urmi Shah and Ben Penglase are associates. Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch is composed of Africa Watch, Americas Watch, Asia Watch, Helsinki Watch, Middle East Watch and the Fund for Free Expression. -

MOZAMBIQUE ZIMBABWE FLOOD REHABILITATION (Appeal 04/2000)

MOZAMBIQUE & ZIMBABWE: Appeal no: 04/2000 (revision no. 4) FLOOD REHABILITATION 17 July 2000 THIS APPEAL SEEKS CHF 17,913,000 IN CASH, KIND AND SERVICES TO ASSIST 400,000 BENEFICIARIES FOR 6 MONTHS With this revision no. 4 of Appeal 04/2000, the total budget is increased to CHF 47,876,955; the increase of CHF 17,913,000 is exclusively related to the proposed Mozambique flood rehabilitation activities outlined below. Flood rehabilitation plans and activities are moving ahead in Botswana and Swaziland and Zimbabwe. Summary In response to the disastrous flooding caused by torrential rains and the effects of Cyclones Connie and Eline in Mozambique, Botswana, Swaziland and Zimbabwe during February and March 2000, the International Federation launched successive revisions of its Appeal no. 04/2000 to provide assistance to affected communities. Mozambique was particularly badly affected, with its three major river basins along the Limpopo, Save and Buzi rivers suffering the most extensive floods in fifty years. The effects of the record rainfall and cyclonic downpours were exacerbated by the opening of sluice gates of dams up river in Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, South Africa and Swaziland. Approximately 4.5 million people, 27% of Mozambique’s population were affected by the flooding, with 700 deaths, almost a hundred missing and 544,000 displaced from their homes. The International Federation’s relief efforts - which reached over 100,000 beneficiaries - were closely coordinated with the Mozambique Red Cross (Cruz Vermelha de Moçambique - CVM). Following the final distributions of ‘reinstallation kits’ to 10,000 families to help them re-establish new homes in late June and early July in six of the affected provinces of Mozambique, the focus of the International Federation and CVM’s activities will now be adjusted.