Knowledge Relativity: Carnarvon Residents' and SKA Personnel's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

14 Northern Cape Province

Section B:Section Profile B:Northern District HealthCape Province Profiles 14 Northern Cape Province John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality (DC45) Overview of the district The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipalitya (previously Kgalagadi) is a Category C municipality located in the north of the Northern Cape Province, bordering Botswana in the west. It comprises the three local municipalities of Gamagara, Ga- Segonyana and Joe Morolong, and 186 towns and settlements, of which the majority (80%) are villages. The boundaries of this district were demarcated in 2006 to include the once north-western part of Joe Morolong and Olifantshoek, along with its surrounds, into the Gamagara Local Municipality. It has an established rail network from Sishen South and between Black Rock and Dibeng. It is characterised by a mixture of land uses, of which agriculture and mining are dominant. The district holds potential as a viable tourist destination and has numerous growth opportunities in the industrial sector. Area: 27 322km² Population (2016)b: 238 306 Population density (2016): 8.7 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 14.5% Cities/Towns: Bankhara-Bodulong, Deben, Hotazel, Kathu, Kuruman, Mothibistad, Olifantshoek, Santoy, Van Zylsrus. Main Economic Sectors: Agriculture, mining, retail. Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh -

Water Resources

CHAPTER 5: WATER RESOURCES CHAPTER 5 Water Resources CHAPTER 5: WATER RESOURCES CHAPTER 5: WATER RESOURCES Integrating Authors P. Hobbs1 and E. Day2 Contributing Authors P. Rosewarne3 S. Esterhuyse4, R. Schulze5, J. Day6, J. Ewart-Smith2,M. Kemp4, N. Rivers-Moore7, H. Coetzee8, D. Hohne9, A. Maherry1 Corresponding Authors M. Mosetsho8 1 Natural Resources and the Environment (NRE), Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Pretoria, 0001 2 Freshwater Consulting Group, Cape Town, 7800 3 Independent Consultant, Cape Town 4 Centre for Environmental Management, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, 9300 5 Centre for Water Resources Research, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Scottsville, 3209 6 Institute for Water Studies, University of Western Cape, Bellville, 7535 7 Rivers-Moore Aquatics, Pietermaritzburg 8 Council for Geoscience, Pretoria, 0184 9 Department of Water and Sanitation, Northern Cape Regional Office, Upington, 8800 Recommended citation: Hobbs, P., Day, E., Rosewarne, P., Esterhuyse, S., Schulze, R., Day, J., Ewart-Smith, J., Kemp, M., Rivers-Moore, N., Coetzee, H., Hohne, D., Maherry, A. and Mosetsho, M. 2016. Water Resources. In Scholes, R., Lochner, P., Schreiner, G., Snyman-Van der Walt, L. and de Jager, M. (eds.). 2016. Shale Gas Development in the Central Karoo: A Scientific Assessment of the Opportunities and Risks. CSIR/IU/021MH/EXP/2016/003/A, ISBN 978-0-7988-5631-7, Pretoria: CSIR. Available at http://seasgd.csir.co.za/scientific-assessment-chapters/ Page 5-1 CHAPTER 5: WATER RESOURCES CONTENTS CHAPTER -

Namaqualand Magisterial District

# # !C # ## # #!C#!C.^# # # # # # # # # ## # # # # ## !C^ ^ ^ ####!C #### # # # # ## # # # !C## # # !C # # !C# ### # ## # # # # !C# # ^ ## # ####!C## !C# # ## ##### ###!C# ## #^ ^ # ## # # ##### !C## # # # ## # ##!C##### !C# # !C### # # # # #!C# ## ##!C^## ## # # ### ## ## # ### # # ## !C#### ## # ######!C# # # # ## ##!C########!C###!C### ###^#!C#### # # # #!C # # # ##!C#### ## ###### #### ####!C#^## ## !C# ## # ## ^ #### ## ##### ######## ### ### # ### # # #!C##########!C######### # ###### ###!C## ##!C#### ##!C# # ### # ## ^# ### ##########^#!C###### ######!C# ### ## ### # !C## ## !C# # !C######!C## # ####!C##### ### #!C# ## # # !C # ### #!C## #!C##!C####!.###!C####!C## ### ## ## # ^!C# # # #!C#### #########^#### # #### # #^ # # !C # # #!C####!C!C####!C # !C# ###!C##^!C#!C#!C# # ### # #!C #### ###^## ############!C### ## #### #!C # # ## # ####!C## # !C!.C## ##!C###!C##### ##### # # # ^ # #!C# # #!C ^ ###^##### # #^# ###### # ##!C## ## # # ## #!C# ### !C# ###!C #!C# !C #!C# !C ###### # #!C # # ## ######!C##!C## # ## ### !C## ####^### !C# # # # # # ## # ## #### # ## # ###!C#^# #!C###### ### #!C#### # # # # ## # # # ## # ### #############!C### ## # # # # # # #!C# # # ## # # ## ## # ##!C ### !C#########!C## ###!C# # # # ## ### # # ## # ## ##!C###### !C# ###!C ## # # #!C # # # ## # #!C## # #!C# ## ####!C!C### ## # # # # ## # # # # # ### #^## ## ###^## # !C### # ## !C# ###### # ## !C^# # # # # ## # # #### ### #!C ### #!C### # ## #!C^!C##!.!C###### # # # ### # !C # # ^ ## #!C# ###!C# ^ ## #### ## # ## # #### # ### ^!C# # # ### ### # ## ## # -

No. 23 Debating Land Reform, Natural DECEMBER Resources and Poverty 2006

No. 23 Debating land reform, natural DECEMBER resources and poverty 2006 Management of some commons in southern Africa: Implications for policy CASS/PLAAS Commons Southern Africa Doreen Atkinson, Michael Taylor and Frank Matose Profound transformations in communal land tenure systems are taking place in parts of southern Africa that have resulted from decades of interventions, particularly the shrinking of the commonage through capture of extensive tracts of lands by private interests. Some policies have been into place that envisage improved management of common rangeland resources through privatisation. However, empirical evidence is lacking as to what extent these may have been successful. Traditional management systems in communal areas have been broken down to the extent that many of them are now more characteristic of open access systems. An alternative to meeting the challenge of managing resources in common rangelands is to develop community-based rangeland resource management systems that build on the strengths of traditional management approaches. Therefore a call is made on the use of indigenous knowledge systems and empowering communities to manage their rangeland resources, in order to prevent open access and promoting improved rangeland management and more sustainable livelihoods. Introduction Formalising common property management regimes, Recognising the dynamics of power into which community- therefore, is one route to legitimate and formalise a form based natural resource management (CBNRM) is inserted of common property ownership on commons that may brings to the fore questions of governance, and the rights, otherwise have been regarded as available for private or lack of rights, which rural dwellers have to access, use, accumulation. -

I Ndian Ocean a T L a N T Ic O C E

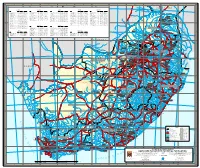

A B C D E F G H J K L 16°E 18°E 20°E 22°E 24°E 26°E 28°E 30°E 32°E S h a s h e M otloutse Tuli Z I M B A B W E Th EASTERN CAPE FREE STATE LIMPOPO NORTH WEST WESTERN CAPE u ne Dam Index Latitude Longitude Dam Index Latitude Longitude Dam Index Latitude Longitude Dam Index Latitude Longitude Dam Index Latitude Longitude 22°S Limpopo Binfield Park Dam.........G8 S32°41'56.8" E26°54'46.6" Allemanskraal Dam.........H5 S28°17'15.9" E27°08'49.4" Albasini Dam..............K2 S23°06'26.0" E30°07'29.0" Bloemhof Dam..............G4 S27°39'52.1" E25°37'11.7" Beaufort West Dam.........E8 S32°20'39.5" E22°35'07.7" Beitbridge 22°S Bushmans Krantz Dam.......G8 S32°21'26.3" E26°40'38.4" Armenia Dam...............H6 S29°21'52.3" E27°07'40.9" Damani Groot Dam..........K1 S22°51'05.2" E30°30'55.9" Boskop Dam................H4 S26°33'41.0" E27°06'41.6" Berg River Dam............C9 S33°54'21.1" E19°03'19.0" Cata Dam..................H8 S32°37'52.9" E27°07'02.8" Erfenis Dam...............G5 S28°30'35.7" E26°46'40.9" Doorndraai Dam............J2 S24°16'48.6" E28°46'37.1" Bospoort Dam..............H3 S25°33'45.4" E27°19'35.5" Buffeljags Dam............D9 S34°01'07.2" E20°32'03.0" 1 Darlington Dam............F8 S33°12'20.3" E25°08'54.4" Fika Patsu Dam............J5 S28°40'21.1" E28°51'24.1" Ebenezer Dam..............J2 S23°56'27.3" E29°59'05.9" Buffelspoort Dam..........H3 S25°46'49.3" E27°29'12.9" Bulshoek Dam..............C7 S31°59'45.8" E18°47'13.7" Musina 1 d De Mistkraal Weir.........G8 S32°57'28.9" E25°40'27.8" Gariep Dam................G6 S30°37'22.1" E25°30'23.7" -

Emthanjeni Municipality Annexure

EMTH ANJENI IDP INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN MAY 2011 MUNICIPALITY EMTHANJENI 45 Voortrekker Street PO Box 42 DE AAR 7000 TEL: 053 632 9100 FAX: 053 631 0105 Website: www.emthanjeni.co.za Email: [email protected]/[email protected] Emthanjeni Municipality IDP Acknowledgement ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS On behalf of Emthanjeni Municipality I would like to express my gratitude to all those who participated in the IDP review process (2011/2012). Among the key contributors to the work, we note the following:- ü The residents and stakeholders of Emthanjeni Municipality who participated in the Community Input sessions. ü All the Emthanjeni Municipality Councillors. ü All the staff in the Directorates of Emthanjeni Municipality. ü The Emthanjeni IDP/Budget and PMS Representative Forum, which met in De Aar during January- February 2011. ü The Executive Committee and IDP/Budget Steering Committee, for providing overall direction. ü Assistance from Pixley Ka Seme District Municipality-Shared Services Executive Committee and Infrastructure Economic Development Committee: BK Markman Mayor GL Nyl Councillor (IEDC) A Jaftha Councillor S Sthonga Chairperson M Malherbe Councillor Emthanjeni IDP/ Budget Steering Committee: I Visser Municipal Manager FM Manuel CFO F Taljaard Director Infrastructure and Housing Services JRM Alexander Manager Corporate Services CP Appies Manager Housing and Project Management MR Jack Manager Development W Lubbe Manager Technical Services Emthanjeni Municipality IDP Acknowledgement H van der Merwe Manager Financial Services CW Jafta LED/IDP Officer Overall support to the process was provided by the Municipality’s IDP unit and Budget Office led by the CFO. Finally, the Office of the Municipal Manager coordinated the IDP review process. -

Group of Experts on Geographical Names -— WORKING PAPER Eleventh Session ~ Geneva, 15-23 October 1984 No

UNITED NATIONS Group of Experts on Geographical Names -— WORKING PAPER Eleventh Session ~ Geneva, 15-23 October 1984 No. 19 Item Ho. 7 of the Provisional Agenda* TOPOHYMIC GUZDELI1SS FOB CARTOGBAPHY - SOOTH AFRICA (1st Edition) (Submitted by Peter E. Raper, South Africa) * WP Ho. 1 Table of Contents PAGE 1 Languages, 3 1.1 General remarks, 3 1.2 Official languages, 3 • 1.2.1 General remarks, 3 1.2.2 The alphabet, 3 1.3 Spelling rules for geographical names, 4 1.3.1 General rules, 4 1.3.2 Afrikaans place-names, 4 1.3.3 Dutch place-names,6 ' 1.3.4 English place-names, 6 1.3.5 Dual forms, 8 1.3.6 Khoekhoen (Hottentot) place-names, 8 1.3.7 . Place-names from Bantu languages, 9 1=4 Pronunciation of South African geographical names, 10 1.4.1 General remarks, 10 1.4.2 Afrikaans, 11 1.5 Linguistic substrata recognizable in place-names of South Africa, 11 - ....•' 2 Names authorities and names .standardization, 12 2.1 The National Place Names Committee, 12 3 Source material, 12 3.1 Maps, 12 3.2 Gazetteers, 12 3.2.1 Official, 12 3.2.2 Private, 13 3.3 Other sources, 13 4 Glossary of appellatives, adjectives and specific terms encountered in South African place-names, 13 4.1 Afrikaans, 13 4.2 Dutch, 18 . • 4.3 English, 18 4.4 Khoekhoen (Hottentot), 18 5 Generic terms encountered in South African place-names, 20 5el General remarks, 20 5.2 Afrikaans, 20 5.3 Khoekhoen, 22 5.3.1 General remarks, 22 6 Administrative division, 23 1 LANGUAGES PAGE 3 1.1 General remarks South Africa is a country in which many languages are spoken, or have been spoken in the past. -

National Groundwater Quality Monitoring Programme

17°0'E 18°0'E 19°0'E 20°0'E 21°0'E 22°0'E 23°0'E 24°0'E 25°0'E S ' S ' 0 0 ° ° 2 2 2 2 National Groundwater Quality Monitoring Programme N O R T H E R N C A P E S ' S ' 0 0 ° ° 3 3 2 The distribution of Geosites 2 as stored in the Water Management System (WMS) Active Geosites (79) Inactive Geosites (33) December 2020 S ' S ' 0 0 ° ° 4 Map Key 4 2 B O T S W A N A 2 Active Geosite Type >! Borehole E Spring Inactive Geosite Type Gaborone >! Borehole H! @ Dug Well S ' S E ' 0 0 ° Spring ° 5 5 2 2 Water Source Dependant Town >! Ngotwane #* #* H! ! Groundwater (GW) Nossob Motswedi H #* H! H! H! H! Surface Water (SW) Sehujwane #* H! >! Lehurutshe H! #* Conjunctive (GW + SW) H! #* #* H!! Other Major Dam Location Mata-Mata > Pomfret Ottoshoop >! H! H! >! >! Tosca S Disaneng #* Mafikeng H! e #* #*! tla #* H Major Dam g S >! Modimola ' o S le Lotlamoreng ' 0 0 ° West End ° 6 >! #* 6 2 Major River iet Plessis 2 P #* >! >H! #*Cashel #* Heuningvlei Tau H! >! H! International Boundary >! Setlagole H! H!#* H!> Provincial Bounadry Twee Rivieren N O >! R T H W E S T ! >! > >! >! H! H! Sannieshof >!H >! Water Management Area (2012) Ganyesa Stella Rietfontein #* >! >!H >H! Katnael >! Delareyville Elevation ! 5 H> Van Zylsrus H! Ottosdal H! K Vaal >! Migdol H! S 0 - 400m H! Vryburg ' u S Askham ru ' 0 m 0 ° >! a ° 7 400 - 800m n >! 7 2 2 800 - 1200m H! Schweizer-Reneke #*Schweitzer Reneke >!>! >!H! s >! Hotazel t >! H! r 1200 - 1600m a H! >! H >! Wolmaransstad 1600 - 2000m Kuruman e >! o Noenieput EH! r 2000 - 2400m >!H >! D ! #* > H! Taung H! Taung 2400 -

Socio-Economic Assessment of SKA Phase 1 in South Africa

Socio-economic Assessment of SKA Phase 1 in South Africa Date: 24 January 2017 Prepared as part of the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for the Phase 1 of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) radio telescope, South Africa Authors: Prof Doreen Atkinson, C2 NRF-rating Researcher, Department of Development Studies, NMMU and Trustee of the Karoo Development Foundation. Rae Wolpe, Managing Director of Impact Economix Adv Hendrik Kotze, Professor extraordinaire at the Africa Centre for Dispute Settlement (ACDS) at the University of Stellenbosch Business School With the assistance of: Sindisile Madyo, Local Economic Development Manager at Pixley ka Seme District Municipality (assistance with interviews and meetings) Caroline Poole, student at the University of Stellenbosch conducting her Master’s thesis on development in Vanwyksvlei (assistance with interviews and research) Lindile Fikizolo, Managing Director of Karoo Dynamics and Trustee of KDF (assistance with interviews and meetings) Peer-reviewed by: Prof Tony Leiman, Associate Professor at the School of Economics of the University of Cape Town (Environmental and resource economics; cost-benefit analysis; informal sector) Dr SW van der Merwe, Senior planner and manager of the Environmental planning department at Dennis Moss Partnership Dr Hugo van der Merwe, Transitional Justice Programme Manager at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation in South Africa. Reviewed by: South African office of the SKA Edited by Paul Lochner, Project Leader of the SKA Phase 1 Strategic Environmental -

Birds of the Karoo Ecology and Conservation

Birds of the Karoo Ecology and Conservation Contents Acknowledgements ii Introduction 1 Aims of this booklet 1 About BirdLife South Africa 1 The Karoo – climate and geography 2 Birds of the Karoo 4 Bird tourism opportunities 7 Species descriptions and ecology 8 Large terrestrial birds and raptors 8 Other raptors/birds of prey 10 Other large birds 14 Waterbirds 15 Other waterbirds 16 Larks 18 Other passerines 23 Managing crow impacts on livestock 33 Habitat management 34 Conclusion 51 References and further reading 52 Cover image: Malachite Sunbird i Acknowledgements This work is based on the research carried out during the BirdLife South Africa Karoo Birds Research and Conservation Project, conducted from 2017-2019, made possible thanks to a donation to BirdLife South Africa from Mrs Gaynor Rupert. In addition, the project partnered with the SANBI Karoo BioGaps Project, supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Number: 98864), awarded through the Foundational Biodiversity Information Programme (FBIP), a joint initia- tive of the Department of Science of Technology (DST), the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI). AL wishes to thank Richard Dean for his time, insights and comments. Domitilla Raimondo of SANBI is thanked for the invitation to become part of the SANBI Karoo BioGaps project. Gigi Laidler and Carol Poole are thanked for all their groundwork. Campbell Fleming is thanked for assistance during surveys during 2017, and Eric Herrmann for hard work in the field in 2018. Thanks to Adrian Craig and Salome Willemse for assistance with atlassing efforts. Thanks to Joseph Steyn, Mark Anderson and Kerry Purnell for comments on drafts of this book. -

Promoting Sustainable Water Service Delivery Within Northern Cape Communities

Presented at the WISA 2000 Conference, 28 May – 1 June 2000, South Africa Promoting sustainable water service delivery within Northern Cape communities Author: Louis Brink Organisation: Department of Water Affairs and Forestry Private Bag X6101 Kimberley 8300 Telephone 053 8314125 Fax 053 8314534 Email- [email protected] 2 Table of Content 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................3 2 THE CUSTOMER .....................................................................................3 2.1 The Needs of the Customer ..................................................................3 2.1.1 Water..............................................................................................3 2.1.2 Sanitation .......................................................................................4 2.1.3 Institutional Capacity ......................................................................4 3 STATUS QUO...........................................................................................5 3.1 Physical .................................................................................................5 3.1.1 Location..........................................................................................5 3.1.2 Climate and Water..........................................................................5 3.1.3 Infrastructure ..................................................................................5 3.2 Institutions .............................................................................................6