Poplar Chap 1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Populusspp. Family: Salicaceae Aspen

Populus spp. Family: Salicaceae Aspen Aspen (the genus Populus) is composed of 35 species which contain the cottonwoods and poplars. Species in this group are native to Eurasia/north Africa [25], Central America [2] and North America [8]. All species look alike microscopically. The word populus is the classical Latin name for the poplar tree. Populus grandidentata-American aspen, aspen, bigtooth aspen, Canadian poplar, large poplar, largetooth aspen, large-toothed poplar, poplar, white poplar Populus tremuloides-American aspen, American poplar, aspen, aspen poplar, golden aspen, golden trembling aspen, leaf aspen, mountain aspen, poplar, popple, quaking asp, quaking aspen, quiver-leaf, trembling aspen, trembling poplar, Vancouver aspen, white poplar Distribution Quaking aspen ranges from Alaska through Canada and into the northeastern and western United States. In North America, it occurs as far south as central Mexico at elevations where moisture is adequate and summers are sufficiently cool. The more restricted range of bigtooth aspen includes southern Canada and the northern United States, from the Atlantic coast west to the prairie. The Tree Aspens can reproduce sexually, yielding seeds, or asexually, producing suckers (clones) from their root system. In some cases, a stand could then be composed of only one individual, genetically, and could be many years old and cover 100 acres (40 hectares) or more. Most aspen stands are a mosaic of several clones. Aspen can reach heights of 120 ft (48 m), with a diameter of 4 ft (1.6 m). Aspen trunks can be quite cylindrical, with little taper and few limbs for most of their length. They also can be very crooked or contorted, due to genetic variability. -

Salicaceae Cottonwood Cottonwood (The Genus Populus) Is Composed of 35 Species Which Contain the Aspens and Poplars

Populus spp. Family: Salicaceae Cottonwood Cottonwood (the genus Populus) is composed of 35 species which contain the aspens and poplars. Species in this group are native to Eurasia/north Africa [25], Central America [2] and North America [8]. All species look alike microscopically. The word populus is the classical Latin name for the poplar tree. Populus angustifolia-balsam, bitter cottonwood, black cottonwood, lanceleaf cottonwood, mountain cottonwood, narrowleaf cottonwood, narrow leaved poplar, Rydberg cottonwood, smoothbark cottonwood, willow cottonwood, willowleaf cottonwood Populus balsamifera-balm, balm of Gilead, balm of Gilead poplar, balm cottonwood, balsam, balsam cottonwood, balsam poplar, bam, black balsam poplar, black cottonwood, black poplar, California poplar, Canadian balsam poplar, Canadian poplar, cottonwax, hackmatack, hairy balm of Gilead, heartleaf balsam poplar, northern black cottonwood, Ontario poplar, tacamahac, tacamahac poplar, toughbark poplar, western balsam poplar Populus deltoides*-aspen cottonwood, big cottonwood, Carolina poplar, cotton tree, eastern cottonwood, eastern poplar, fremont cottonwood, great plains cottonwood, Missourian poplar, necklace poplar, northern fremont cottonwood, palmer cottonwood, plains cottonwood, Rio Grande cottonwood, river cottonwood, river poplar, southern cottonwood, Tennessee poplar, Texas cottonwood, valley cottonwood, Vermont poplar, Virginia poplar, water poplar, western cottonwood, whitewood, wislizenus cottonwood, yellow cottonwood Populus fremontii-Arizona cottonwood, -

Observations on Seeds Fremont Cottonwood

Observations on Seeds and Seedlings of Fremont Cottonwood Item Type Article Authors Fenner, Pattie; Brady, Ward W.; Patton, David R. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 29/09/2021 03:42:35 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552248 Fenner, Brady and Patton Fremont Cottonwood 55 where moisture is more constantly available than near the ObservationsonSeeds surface. Keywords: cottonwood, riparian, seed germination. The collection of data on natural river /floodplain ecosystems in the Southwest is of immediate concern because they are and Seedlings of rapidly being modified by construction of dams, wells and irrigation projects, channel alteration, phreatophyte control Fremont Cottonwood projects, and by clearing for agriculture. Additional information is needed on how these activities modify the environment and the subsequent effect on germination and establishment of Fremont Cottonwood. Pattie Fenner Both the importance and the diminished extent of riparian areas of the southwest have been acknowledged (Johnson and Arizona State University Jones, 1977). This has led to increased emphasis on under- standing ecological characteristics of major riparian species. Ward W. Bradyl This paper describes some characteristics of one riparian Arizona State University species, Fremont Cottonwood (Populus fremontii Wats). The characteristics are: seed viability under various storage condi- tions, effects of moisture stress on germination, and rates of and David R. Patton2 seedling root growth. Knowledge of these characteristics is Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station important for understanding seedling ecology of the species, USDA Forest Service which, in turn, increases understanding of the dynamics of the riparian community as a whole. -

Checklist of Common Native Plants the Diversity of Acadia National Park Is Refl Ected in Its Plant Life; More Than 1,100 Plant Species Are Found Here

National Park Service Acadia U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park Checklist of Common Native Plants The diversity of Acadia National Park is refl ected in its plant life; more than 1,100 plant species are found here. This checklist groups the park’s most common plants into the communities where they are typically found. The plant’s growth form is indicated by “t” for trees and “s” for shrubs. To identify unfamiliar plants, consult a fi eld guide or visit the Wild Gardens of Acadia at Sieur de Monts Spring, where more than 400 plants are labeled and displayed in their habitats. All plants within Acadia National Park are protected. Please help protect the park’s fragile beauty by leaving plants in the condition that you fi nd them. Deciduous Woods ash, white t Fraxinus americana maple, mountain t Acer spicatum aspen, big-toothed t Populus grandidentata maple, red t Acer rubrum aspen, trembling t Populus tremuloides maple, striped t Acer pensylvanicum aster, large-leaved Aster macrophyllus maple, sugar t Acer saccharum beech, American t Fagus grandifolia mayfl ower, Canada Maianthemum canadense birch, paper t Betula papyrifera oak, red t Quercus rubra birch, yellow t Betula alleghaniesis pine, white t Pinus strobus blueberry, low sweet s Vaccinium angustifolium pyrola, round-leaved Pyrola americana bunchberry Cornus canadensis sarsaparilla, wild Aralia nudicaulis bush-honeysuckle s Diervilla lonicera saxifrage, early Saxifraga virginiensis cherry, pin t Prunus pensylvanica shadbush or serviceberry s,t Amelanchier spp. cherry, choke t Prunus virginiana Solomon’s seal, false Maianthemum racemosum elder, red-berried or s Sambucus racemosa ssp. -

Effects of Salinity on Establishment of Populus Fremontii (Cottonwood) and Tamarix Ramosissima (Saltcedar) in Southwestern United States

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 55 Number 1 Article 6 1-16-1995 Effects of salinity on establishment of Populus fremontii (cottonwood) and Tamarix ramosissima (saltcedar) in southwestern United States Patrick B. Shafroth National Biological Survey, Midcontinent Ecological Science Center, Fort Collins, Colorado Jonathan M. Friedman National Biological Survey, Midcontinent Ecological Science Center, Fort Collins, Colorado Lee S. Ischinger National Biological Survey, Midcontinent Ecological Science Center, Fort Collins, Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Shafroth, Patrick B.; Friedman, Jonathan M.; and Ischinger, Lee S. (1995) "Effects of salinity on establishment of Populus fremontii (cottonwood) and Tamarix ramosissima (saltcedar) in southwestern United States," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 55 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol55/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Nntur-a1iJ'it 5S(1), © 1995. pp. 58-65 EFFECTS OF SALINITY ON ESTABLISHMENT OF POPULUS FREMONTII (COTTONWOOD) AND TAMARlX RAMOSISSIMA (SALTCEDAR) IN SOUTHWESTERN UNITED STATES Patrick B. ShafrothL• Jonathan M. Friedmanl, and Lee S. IschingerL AB!'>"TR.ACT.-The exotic shmb Tamarix ramnsissima (saltcedar) has replaced the native Populusfremont# (cottonwood) along many streams in southwestern United States. We u.sed a controlled outdoor experiment to examine the influence of river salinity on germination and first-year survival of P. fremcnlii var. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

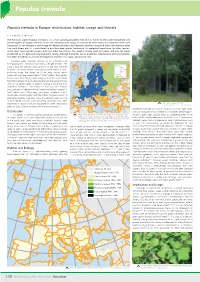

Populus Tremula

Populus tremula Populus tremula in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats G. Caudullo, D. de Rigo The Eurasian aspen (Populus tremula L.) is a fast-growing broadleaf tree that is native to the cooler temperate and boreal regions of Europe and Asia. It has an extremely wide range, as a result of which there are numerous forms and subspecies. It can tolerate a wide range of habitat conditions and typically colonises disturbed areas (for example after fire, wind-throw, etc.). It is considered to be a keystone species because of its ecological importance for other species: it has more host-specific species than any other boreal tree. The wood is mainly used for veneer and pulp for paper production as it is light and not particularly strong, although it also has use as a biomass crop because of its fast growth. A number of hybrids have been developed to maximise its vigour and growth rate. Eurasian aspen (Populus tremula L.) is a medium-size, fast-growing tree, exceptionally reaching a height of 30 m1. The Frequency trunk is long and slender, rarely up to 1 m in diameter. The light < 25% branches are rather perpendicular, giving to the crown a conic- 25% - 50% 50% - 75% pyramidal shape. The leaves are 5-7 cm long, simple, round- > 75% ovate, with big wave-shaped teeth2, 3. They flutter in the slightest Chorology Native breeze, constantly moving and rustling, so that trees can often be heard but not seen. In spring the young leaves are coppery-brown and turn to golden yellow in autumn, making it attractive in all vegetative seasons1, 2. -

Poplars and Willows: Trees for Society and the Environment / Edited by J.G

Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment This volume is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Victor Steenackers. Vic, as he was known to his friends, was born in Weelde, Belgium, in 1928. His life was devoted to his family – his wife, Joanna, his 9 children and his 23 grandchildren. His career was devoted to the study and improve- ment of poplars, particularly through poplar breeding. As Director of the Poplar Research Institute at Geraardsbergen, Belgium, he pursued a lifelong scientific interest in poplars and encouraged others to share his passion. As a member of the Executive Committee of the International Poplar Commission for many years, and as its Chair from 1988 to 2000, he was a much-loved mentor and powerful advocate, spreading scientific knowledge of poplars and willows worldwide throughout the many member countries of the IPC. This book is in many ways part of the legacy of Vic Steenackers, many of its contributing authors having learned from his guidance and dedication. Vic Steenackers passed away at Aalst, Belgium, in August 2010, but his work is carried on by others, including mem- bers of his family. Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment Edited by J.G. Isebrands Environmental Forestry Consultants LLC, New London, Wisconsin, USA and J. Richardson Poplar Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Published by The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and CABI CABI is a trading name of CAB International CABI CABI Nosworthy Way 38 Chauncey Street Wallingford Suite 1002 Oxfordshire OX10 8DE Boston, MA 02111 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 800 552 3083 (toll free) Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Tel: +1 (0)617 395 4051 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cabi.org © FAO, 2014 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. -

Climatic Change Can Influence Species Diversity Patterns and Potential Habitats of Salicaceae Plants in China

Article Climatic Change Can Influence Species Diversity Patterns and Potential Habitats of Salicaceae Plants in China WenQing Li 1, MingMing Shi 1, Yuan Huang 2, KaiYun Chen 1, Hang Sun 1 and JiaHui Chen 1,* 1 CAS Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China; [email protected] (W.L.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (K.C.); [email protected] (H.S.) 2 School of Life Sciences, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, Yunnan 650092, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.C.) Received: 18 January 2019; Accepted: 25 February 2019; Published: 1 March 2019 Abstract: Salicaceae is a family of temperate woody plants in the Northern Hemisphere that are highly valued, both ecologically and economically. China contains the highest species diversity of these plants. Despite their widespread human use, how the species diversity patterns of Salicaceae plants formed remains mostly unknown, and these may be significantly affected by global climate warming. Using past, present, and future environmental data and 2673 georeferenced specimen records, we first simulated the dynamic changes in suitable habitats and population structures of Salicaceae. Based on this, we next identified those areas at high risk of habitat loss and population declines under different climate change scenarios/years. We also mapped the patterns of species diversity by constructing niche models for 215 Salicaceae species, and assessed the driving factors affecting their current diversity patterns. The niche models showed Salicaceae family underwent extensive population expansion during the Last Inter Glacial period but retreated to lower latitudes during and since the period of the Last Glacial Maximum. -

Apocheima Cinerarius Erschoff

remote sensing Article Assessment of Poplar Looper (Apocheima cinerarius Erschoff) Infestation on Euphrates (Populus euphratica) Using Time-Series MODIS NDVI Data Based on the Wavelet Transform and Discriminant Analysis Tiecheng Huang 1,2, Xiaojuan Ding 2, Xuan Zhu 3 , Shujiang Chen 2, Mengyu Chen 1, Xiang Jia 1, Fengbing Lai 2 and Xiaoli Zhang 1,* 1 Beijing Key Laboratory of Precision Forestry, Forestry College, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (X.J.) 2 College of Geographical Science and Tourism, Xinjiang Normal University, Urumqi 830054, China; [email protected] (X.D.); [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (F.L.) 3 School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment, Clayton Campus, Monash University, Clayton 3800, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-010-62336227 Abstract: Poplar looper (Apocheima cinerarius Erschoff) is a destructive insect infesting Euphrates or desert poplars (Populus euphratica) in Xinjiang, China. Since the late 1950s, it has been plaguing Citation: Huang, T.; Ding, X.; Zhu, desert poplars in the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang and caused widespread damages. This paper presents X.; Chen, S.; Chen, M.; Jia, X.; Lai, F.; an approach to the detection of poplar looper infestations on desert poplars and the assessment of Zhang, X. Assessment of Poplar the severity of the infestations using time-series MODIS NDVI data via the wavelet transform and Looper (Apocheima cinerarius Erschoff) discriminant analysis, using the middle and lower reaches of the Yerqiang River as a case study. -

"A Most Dangerous Tree": the Lombardy Poplar in Landscape Gardening

"A Most Dangerous Tree": The Lombardy Poplar in Landscape Gardening Christina D. Wood ~ The history of the Lombardy poplar in America illustrates that there are fashions in trees just as in all else. "The Lombardy poplar," wrote Andrew Jackson may have originated in Persia or perhaps the Downing in 1841, "is too well known among Himalayan region; because the plant was not us to need any description."’ This was an ex- mentioned in Roman agricultural texts, writ- traordinary thing to say about a tree that had ers reasoned that it must have been introduced been introduced to North America less than to Italy from central Asia.3 But subsequent sixty years earlier. In that short time, this writers have thought it more likely that the distinctive cultivar of dominating height Lombardy sprang up as a mutant of the black had gained notoriety due to aggressive over- poplar. Augustine Henry found evidence that planting in the years just after its introduction. it originated between 1700 and 1720 in Lom- The Lombardy poplar (Populus nigra bardy and spread worldwide by cuttings, reach- ’Italica’) is a very tall, rapidly growing tree ing France in 1749, England in 1758, and North with a distinctively columnar shape, often America in 1784.4 It was soon widely planted with a buttressed base. It is a fastigiate muta- in Europe as an avenue tree, as an ornamental, tion of a male black poplar (P. nigra).2 As a and for a time, for its timber. According to at member of the willow family (Salicaceae)- least one source, it was used in Italy to make North American members of the genus in- crates for grapes until the early nineteenth clude the Eastern poplar (Populus deltoides), century, when its wood was abandoned for this bigtooth aspen (Populus granditata), and purpose in favor of that of P. -

Populus Alba White Poplar1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-499 October 1994 Populus alba White Poplar1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION White Poplar is a fast-growing, deciduous tree which reaches 60 to 100 feet in height with a 40 to 50-foot-spread and makes a nice shade tree, although it is considered short-lived (Fig. 1). The dark green, lobed leaves have a fuzzy, white underside which gives the tree a sparkling effect when breezes stir the leaves. These leaves are totally covered with this white fuzz when they are young and first open. The fall color is pale yellow. The flowers appear before the leaves in spring but are not showy, and are followed by tiny, fuzzy seedpods which contain numerous seeds. It is the white trunk and bark of white poplar which is particularly striking, along with the beautiful two-toned leaves. The bark stays smooth and white until very old when it can become ridged and furrowed. The wood of White Poplar is fairly brittle and subject to breakage in storms and the soft bark is subject to injury from vandals. Leaves often drop from the tree beginning in summer and continue dropping through the fall. Figure 1. Middle-aged White Poplar. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Populus alba DESCRIPTION Pronunciation: POP-yoo-lus AL-buh Common name(s): White Poplar Height: 60 to 100 feet Family: Salicaceae Spread: 40 to 60 feet USDA hardiness zones: 4 through 9 (Fig. 2) Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette Origin: not native to North America Crown shape: oval Uses: reclamation plant; shade tree; no proven urban toleranceCrown density: open Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out Growth rate: fast of the region to find the tree Texture: coarse 1.