Pacific Nations Broadcasting I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Vietnam: Victims of Trafficking

Country Policy and Information Note Vietnam: Victims of trafficking Version 4.0 April 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

The Meeting Place. Radio Features in the Shina Language of Gilgit

Georg Buddruss and Almuth Degener The Meeting Place Radio Features in the Shina Language of Gilgit by Mohammad Amin Zia Text, interlinear Analysis and English Translation with a Glossary 2012 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 1432-6949 ISBN 978-3-447-06673-0 Contents Preface....................................................................................................................... VII bayáak 1: Giving Presents to Our Friends................................................................... 1 bayáak 2: Who Will Do the Job? ............................................................................... 47 bayáak 3: Wasting Time............................................................................................. 85 bayáak 4: Cleanliness................................................................................................. 117 bayáak 5: Sweet Water............................................................................................... 151 bayáak 6: Being Truly Human.................................................................................... 187 bayáak 7: International Year of Youth........................................................................ 225 References.................................................................................................................. 263 Glossary..................................................................................................................... 265 Preface Shina is an Indo-Aryan language of the Dardic group which is spoken in several -

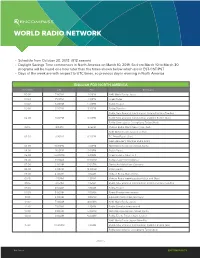

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will fin d a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Review of Content Regulation Models

Issues facing broadcast content regulation MILLWOOD HARGRAVE LTD. Authors: Andrea Millwood Hargrave, Geoff Lealand, Paul Norris, Andrew Stirling Disclaimer The report is based on collaborative desk research conducted for the New Zealand Broadcasting Standards Authority over a two month period. Issue date November 2006 © Broadcasting Standards Authority, New Zealand Contents Aim and Scope of this Report..................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary.................................................................................................... 4 A: Introduction............................................................................................................. 6 Background............................................................................................................. 6 Definitions............................................................................................................... 9 What is the justification for regulation?.................................................................... 9 Protective content regulation: an overview............................................................ 10 Proactive content regulation: an overview............................................................. 12 Co-regulation and self-regulation........................................................................... 12 Technological changes and convergence.............................................................. 15 Differences in devices.......................................................................................... -

The Vietnam Consumer Survey an Accelerating Momentum January 2020 Foreword 03 an Accelerating Momentum 04 the Vietnam Consumer Survey 07 1

The Vietnam Consumer Survey An accelerating momentum January 2020 Foreword 03 An accelerating momentum 04 The Vietnam Consumer Survey 07 1. Consumer sentiment 09 2. Consumer awareness 13 3. Purchasing preferences 16 4. Purchasing behaviours 22 5. Payment preferences 29 6. Post-purchase loyalty 31 Looking ahead 33 Contact us 35 Foreword After three decades of economic reform, Vietnam has transformed into one of the most dynamic emerging markets in the Southeast Asia region. This momentum looks set to accelerate in the near-term, as its economy continues to show fundamental strength on the back of strong export demand, and a concerted nationwide push for digital transformation. In this first edition of the Vietnam Consumer Survey, we explore some of the latest consumer behaviour patterns emerging from the results of our survey conducted in the second half of 2019 across 1,000 respondents through face-to-face interviews in four cities: Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Can Tho, and Da Nang. We have structured this report in a sequential manner to trace the consumers’ journey from pre-consumption to consumption, and finally post-consumption. While it is worthwhile noting that the consumer’s journey may not always follow this linear pattern, what we endeavour to do in this report is to provide you with a more holistic understanding of some of the drivers and motivations behind the Vietnamese consumer’s behaviours. We will begin this journey in the pre-consumption phase, where we take stock of the overall consumer sentiment, and their outlook of the future, before examining their preferred communication channels, and purchasing preferences. -

Pakistan's Institutions

Pakistan’s Institutions: Pakistan’s Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Work They But How Can Matter, They Know We Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman and Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Essays by Madiha Afzal Ishrat Husain Waris Husain Adnan Q. Khan, Asim I. Khwaja, and Tiffany M. Simon Michael Kugelman Mehmood Mandviwalla Ahmed Bilal Mehboob Umar Saif Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain ©2018 The Wilson Center www.wilsoncenter.org This publication marks a collaborative effort between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Asia Program and the Fellowship Fund for Pakistan. www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program fffp.org.pk Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Cover: Parliament House Islamic Republic of Pakistan, © danishkhan, iStock THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broader policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. -

Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines

Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines Working Paper No. 275 CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) Rex L. Navarro Renz Louie V. Celeridad Rogelio P. Matalang Hector U. Tabbun Leocadio S. Sebastian 1 Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines Working Paper No. 275 CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) Rex L. Navarro Renz Louie V. Celeridad Rogelio P. Matalang Hector U. Tabbun Leocadio S. Sebastian 2 Correct citation: Navarro RL, Celeridad RLV, Matalang RP, Tabbun HU, Sebastian LS. 2019. Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines. CCAFS Working Paper no. 275. Wageningen, the Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org Titles in this Working Paper series aim to disseminate interim climate change, agriculture and food security research and practices and stimulate feedback from the scientific community. The CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) is a strategic partnership of CGIAR and Future Earth, led by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). The Program is carried out with funding by CGIAR Fund Donors, Australia (ACIAR), Ireland (Irish Aid), Netherlands (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Trade; Switzerland (SDC); Thailand; The UK Government (UK Aid); USA (USAID); The European Union (EU); and with technical support from The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). For more information, please visit https://ccafs.cgiar.org/donors. Contact: CCAFS Program Management Unit, Wageningen University & Research, Lumen building, Droevendaalsesteeg 3a, 6708 PB Wageningen, the Netherlands. -

Abstract a Case Study of Cross-Ownership Waivers

ABSTRACT A CASE STUDY OF CROSS-OWNERSHIP WAIVERS: FRAMING NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF RUPERT MURDOCH’S REQUESTS TO KEEP THE NEW YORK POST by Rachel L. Seeman Media ownership is an important regulatory issue that is enforced by the Federal Communications Commission. The FCC, Congress, court and public interest groups share varying viewpoints concerning what the ownership limits should be and whether companies should be granted a waiver to be excused from the rules. News Corporation is one media firm that has a history of seeking these waivers, particularly for the New York Post and television stations in same community. This study conducted a qualitative framing analysis of news articles from the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal to determine if the viewpoints expressed by the editorial boards were reflected in reports on News Corp.’s attempt to receive cross-ownership waivers. The analysis uncovered ten frames the newspapers used to assist in reporting the events and found that 80% of these frames did parallel the positions the paper’s editorial boards took concerning ownership waivers. A CASE STUDY OF CROSS-OWNERSHIP WAIVERS: FRAMING NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF RUPERT MURDOCH’S REQUESTS TO KEEP THE NEW YORK POST A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications by Rachel Leianne Seeman Miami University Oxford, OH 2009 Advisor: __________________________________ (Dr. Bruce Drushel) Reader: __________________________________ (Dr. Howard -

The Linguistic Debate in Chile: Ideologies and Representations of Languages and Multilingual Practices in the National Online News

The linguistic debate in Chile: ideologies and representations of languages and multilingual practices in the national online news HANNA SLIASHYNSKAYA Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Newcastle University School of Education, Communication and Language Sciences July 2019 ii Abstract Linguistic ideologies, or beliefs about languages and their use, are key to dynamics and changes in language choice, language minorisation and death. Linguistic ideologies, especially those of monolingualism, have long been part of nation-states’ policies (Shohamy, 2006; Fairclough, 2015) despite the prevalence of multilingualism in social domains (Meyerhoff, 2008). Chile, the context of this research project, is a multilingual country with a surprisingly limited amount of language legislation (Leclerc, 2015) most of which focuses on governmental plans to make Chile bilingual by 2030 (Minsegpres, Mineduc and Minec, 2014) and the foreign language education in schools, namely, the teaching of English, the only foreign language taught in public schools since 2010. At the same time, the use of indigenous languages is not regulated, and Spanish is the de facto official language. In view of such laissez-faire regulations of Chile’s linguistic setting, it is crucial to explore public domains beyond language policy to explain the ongoing minoritisation of indigenous languages and the growth of the dominant languages. Thus, this thesis examines how dominant and minoritised languages are represented in popular national online newspapers. The collected data includes 8877 news articles published in ten most widely-read Chilean online newspapers between 2010 and 2016 and containing references to Chile’s local (Mapudungún, Rapa Nui, Aimara, Quechua, Yámana, Huilliche, Qawasqar, Kunza and Spanish) and foreign languages (English), as well as variously labelled multilingual practices, such as bilingualism and multilingualism. -

Telenovela, Reception and Social Debate1 Telenovela, Recepción Y Debate Social

AMIGO, B., BRAVO, M. y OSORIO, F. Soap operas, reception and social debate CUADERNOS.INFO Nº 35 ISSN 0719-3661 Versión electrónica: ISSN 0719-367x http://www.cuadernos.info doi: 10.7764/cdi.35.654 Received: 10-15-2014 / Accepted: 11-25-2014 Telenovela, reception and social debate1 Telenovela, recepción y debate social BERNARDO AMIGO, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile ([email protected]) MARÍA CECILIA BRAVO, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile ([email protected]) FRANCISCO OSORIO, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile ([email protected]) ABSTRACT RESUMEN The essay summarises qualitative empirical research El artículo sintetiza un conjunto de investigaciones on Chilean television carried out between 2007 and empíricas cualitativas sobre la ficción televisiva en 2014. The article focuses on the interactive mecha- Chile, realizadas entre 2007 y 2014. Específicamente, nism that mutually influences television and viewers se centra en los mecanismos de interacción que se through fiction (telenovela). It concludes that the configuran entre la televisión y los telespectadores a dynamic of social debate can influence the symbo- través del género televisivo de la telenovela. Concluye lic conditions for the production of television dis- que las dinámicas del debate social pueden influir course, argument that opposes the classic thesis of en las condiciones simbólicas para la producción de television direct effects on society. discursos en la televisión, argumento que es contrario a la tesis clásica de los efectos directos de la televisión en la sociedad. Keywords: Telenovela, identification, media representa- Palabras clave: Telenovela, identificación, representación tion, social uses, gender. mediática, usos sociales, género. •How to cite: Amigo,CUADERNOS.INFO B., Bravo, M.