Taxonomy of Tricholoma in Northern Europe Based on ITS Sequence Data and Morphological Characters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strážovské Vrchy Mts., Resort Podskalie; See P. 12)

a journal on biodiversity, taxonomy and conservation of fungi No. 7 March 2006 Tricholoma dulciolens (Strážovské vrchy Mts., resort Podskalie; see p. 12) ISSN 1335-7670 Catathelasma 7: 1-36 (2006) Lycoperdon rimulatum (Záhorská nížina Lowland, Mikulášov; see p. 5) Cotylidia pannosa (Javorníky Mts., Dolná Mariková – Kátlina; see p. 22) March 2006 Catathelasma 7 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIODIVERSITY OF FUNGI Lycoperdon rimulatum, a new Slovak gasteromycete Mikael Jeppson 5 Three rare tricholomoid agarics Vladimír Antonín and Jan Holec 11 Macrofungi collected during the 9th Mycological Foray in Slovakia Pavel Lizoň 17 Note on Tricholoma dulciolens Anton Hauskknecht 34 Instructions to authors 4 Editor's acknowledgements 4 Book notices Pavel Lizoň 10, 34 PHOTOGRAPHS Tricholoma dulciolens Vladimír Antonín [1] Lycoperdon rimulatum Mikael Jeppson [2] Cotylidia pannosa Ladislav Hagara [2] Microglossum viride Pavel Lizoň [35] Mycena diosma Vladimír Antonín [35] Boletopsis grisea Petr Vampola [36] Albatrellus subrubescens Petr Vampola [36] visit our web site at fungi.sav.sk Catathelasma is published annually/biannually by the Slovak Mycological Society with the financial support of the Slovak Academy of Sciences. Permit of the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak rep. no. 2470/2001, ISSN 1335-7670. 4 Catathelasma 7 March 2006 Instructions to Authors Catathelasma is a peer-reviewed journal devoted to the biodiversity, taxonomy and conservation of fungi. Papers are in English with Slovak/Czech summaries. Elements of an Article Submitted to Catathelasma: • title: informative and concise • author(s) name(s): full first and last name (addresses as footnote) • key words: max. 5 words, not repeating words in the title • main text: brief introduction, methods (if needed), presented data • illustrations: line drawings and color photographs • list of references • abstract in Slovak or Czech: max. -

Major Clades of Agaricales: a Multilocus Phylogenetic Overview

Mycologia, 98(6), 2006, pp. 982–995. # 2006 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview P. Brandon Matheny1 Duur K. Aanen Judd M. Curtis Laboratory of Genetics, Arboretumlaan 4, 6703 BD, Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Wageningen, The Netherlands Worcester, Massachusetts, 01610 Matthew DeNitis Vale´rie Hofstetter 127 Harrington Way, Worcester, Massachusetts 01604 Department of Biology, Box 90338, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Graciela M. Daniele Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biologı´a Vegetal, M. Catherine Aime CONICET-Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Casilla USDA-ARS, Systematic Botany and Mycology de Correo 495, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina Laboratory, Room 304, Building 011A, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, Maryland 20705-2350 Dennis E. Desjardin Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, Jean-Marc Moncalvo San Francisco, California 94132 Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Royal Ontario Museum and Department of Botany, University Bradley R. Kropp of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6 Canada Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 Zai-Wei Ge Zhu-Liang Yang Lorelei L. Norvell Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Pacific Northwest Mycology Service, 6720 NW Skyline Sciences, Kunming 650204, P.R. China Boulevard, Portland, Oregon 97229-1309 Jason C. Slot Andrew Parker Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, 127 Raven Way, Metaline Falls, Washington 99153- Worcester, Massachusetts, 01609 9720 Joseph F. Ammirati Else C. Vellinga University of Washington, Biology Department, Box Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3102 Timothy J. -

Key Features for the Identification of the Fungi in This Guide

Further information Key features for the identifi cation Saprotrophic recycler fungi Books and References of the fungi in this guide Mushrooms. Roger Phillips (2006). Growth form. Fungi come in many different shapes and Fruit body colours. The different parts of the fruit body Collybia acervata Conifer Toughshank. Cap max. 5cm. Macmillan. Excellent photographs and descriptions including sizes. In this fi eld guide most species are the classic can be differently coloured and it is also important This species grows in large clusters often on the ground many species from pinewoods and other habitats. toadstool shape with a cap and stem but also included to remember that the caps sometimes change colour but possibly growing on buried wood. Sometimes there are are some that grow out of wood like small shelves or completely or as they dry out. Making notes or taking Fungi. Roy Watling and Stephen Ward (2003). several clusters growing ± in a ring. The caps are reddish brackets and others that have a coral- like shape. Take photographs can help you remember what they looked Naturally Scottish Series. Scottish Natural Heritage, Battleby, Perth. brown but dry out to a buff colour. The stems are smooth, note of whether the fungus is growing alone, trooping like when fresh. In some fungi the fl esh changes colour Good introduction to fungi in Scotland. and red brown and the gills are white and variably attached, or in a cluster. when it is damaged. Try cutting the fungus in half or Fungi. Brian Spooner and Peter Roberts (2005). adnate to free. Spore print white. -

Matsis and Wannabees: a Primer on Pine Mushrooms

Britt A. Bunyard [email protected] Figure 1. Three matsutakes? Look again. These three Tricholoma species were collected by John Sparks in New Mexico and growing within 100 feet of one another. From left to right, Tricholoma focale, T. caligatum, and T. magnivelare. Identifications were confirmed with DNA analysis by Dr. Clark Ovrebo. Photo courtesy of J. Sparks. described (Arora, 1979). And what of rumors that we have the “true” matsutake of Asia in parts of North America? Whether you call it pine mushroom or matsutake (or simply the more affectionate nickname “matsi”), there can be no question that this mushroom is one of the most highly prized in the world. It can be an acquired taste to Westerners (I personally love them!); among Japanese this mushroom is king, with prices for top specimens fetching kings’ ransoms. Annually, Japanese matsutake mavens will spend US$50-100 for a single top quality specimen and prices many times this are regularly reported. Because the demand far f you reside in Canada you likely call exceeds the supply in Japan (97% of them pine mushrooms; in the USA, matsutake mushrooms consumed in most refer to them by their Japanese Japan, annually, are imported, according Iname, matsutake. Is it Tricholoma to the Japanese Tariff Association magnivelare or T. matsutake? And what [Ota et al., 2012]), commercial about those other matsi lookalikes? pickers descend upon North America Some smell remarkably similar to the (especially in the Pacific Northwest) Figure 2. Catathelasma imperiale “provocative compromise between every autumn with hopes of striking red hots and dirty socks” that Arora from Vancouver Island, British gold. -

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella Species

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Printed in Eko-trykk A/S, Førde, Norway Printing date: 1. August 1995 ISBN 82-90724-14-4 ISSN 0802-4966 A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway 6 Authors address: Center for Forest Mycology Research Forest Products Laboratory United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service One Gifford Pinchot Dr. Madison, WI 53705 USA ABSTRACT Once a taxonomic refugium for nearly any white-spored agaric with an annulus and attached gills, the concept of the genus Armillaria has been clarified with the neotypification of Armillaria mellea (Vahl:Fr.) Kummer and its acceptance as type species of Armillaria (Fr.:Fr.) Staude. Due to recognition of different type species over the years and an extremely variable generic concept, at least 274 species and varieties have been placed in Armillaria (or in Armillariella Karst., its obligate synonym). Only about forty species belong in the genus Armillaria sensu stricto, while the rest can be placed in forty-three other modem genera. This study is based on original descriptions in the literature, as well as studies of type specimens and generic and species concepts by other authors. This publication consists of an alphabetical listing of all epithets used in Armillaria or Armillariella, with their basionyms, currently accepted names, and other obligate and facultative synonyms. -

Ricken and Artificial Selection on Primorsky Krai Territory

Gukov, G.V, Rozlomiy, N.G. /Vol. 8 Núm. 18: 432- 437/ Enero-febrero 2019 432 Articulo de investigación Biological and environmental peculiarities of tricholoma caligatum (viv) ricken and artificial selection on Primorsky Krai territory Particularidades biológicas y ambientales de tricholoma caligatum (viv) ricken y selección artificial en el territorio de Primorsky Krai Particularidades biológicas e ambientais do tricomaloma caligatum (vida) e seleção artificial no território do Krai de Primorsky Recibido: 16 de enero de 2019. Aceptado: 06 de febrero de 2019 Written by: Gukov G.V. (Corresponding Author)133 Rozlomiy N.G.134 Abstract Resumen Matsutake mushroom is unique in many ways - it El hongo Matsutake es único en muchos has several names, including two Latin ones, aspectos: tiene varios nombres, entre ellos dos mycorhiza developer, and selects individual latinos, desarrollador de micorhiza, y selecciona conifers or hardwood specifically as the partners coníferas individuales o madera dura from woody plant species in different countries. específicamente como socios de especies de It is hidden and very shy - the main part of its fruit plantas leñosas en diferentes países. Es oculto y body (leg) is hidden in soil, and the small compact muy tímido: la parte principal de su cuerpo frutal cap of the fungus is not always visible in forest (pierna) está oculta en el suelo, y la pequeña capa among the fallen autumn needles and leaves. The compacta del hongo no siempre es visible en el mushroom is also unique as it has exceptional bosque entre las hojas y las agujas otoñales nutritional and medicinal properties, therefore caídas. El hongo también es único ya que tiene the price for this unique species exceeds all propiedades nutricionales y medicinales reasonable limits. -

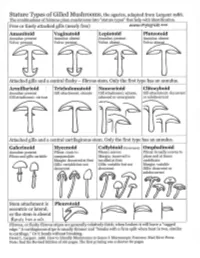

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Checklist of the Species of the Genus Tricholoma (Agaricales, Agaricomycetes) in Estonia

Folia Cryptog. Estonica, Fasc. 47: 27–36 (2010) Checklist of the species of the genus Tricholoma (Agaricales, Agaricomycetes) in Estonia Kuulo Kalamees Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, 40 Lai St. 51005, Tartu, Estonia. Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Estonian University of Life Sciences, 181 Riia St., 51014 Tartu, Estonia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: 42 species of genus Tricholoma (Agaricales, Agaricomycetes) have been recorded in Estonia. A checklist of these species with ecological, phenological and distribution data is presented. Kokkukvõte: Perekonna Tricholoma (Agaricales, Agaricomycetes) liigid Eestis Esitatakse kriitiline nimestik koos ökoloogiliste, fenoloogiliste ja levikuliste andmetega heiniku perekonna (Tricholoma) 42 liigi (Agaricales, Agaricomycetes) kohta Eestis. INTRODUCTION The present checklist contains 42 Tricholoma This checklist also provides data on the ecol- species recorded in Estonia. All the species in- ogy, phenology and occurrence of the species cluded (except T. gausapatum) correspond to the in Estonia (see also Kalamees, 1980a, 1980b, species conceptions established by Christensen 1982, 2000, 2001b, Kalamees & Liiv, 2005, and Heilmann-Clausen (2008) and have been 2008). The following data are presented on each proved by relevant exsiccates in the mycothecas taxon: (1) the Latin name with a reference to the TAAM of the Institute of Agricultural and Envi- initial source; (2) most important synonyms; (3) ronmental Sciences of the Estonian University reference to most important and representative of Life Sciences or TU of the Natural History pictures (iconography) in the mycological litera- Museum of the Tartu University. In this paper ture used in identifying Estonian species; (4) T. gausapatum is understand in accordance with data on the ecology, phenology and distribution; Huijsman, 1968 and Bon, 1991. -

Taxonomy, Ecology and Distribution of Melanoleuca Strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe

CZECH MYCOLOGY 69(1): 15–30, MAY 9, 2017 (ONLINE VERSION, ISSN 1805-1421) Taxonomy, ecology and distribution of Melanoleuca strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe 1 2 3 4 ONDREJ ĎURIŠKA ,VLADIMÍR ANTONÍN ,ROBERTO PARA ,MICHAL TOMŠOVSKÝ , 5 SOŇA JANČOVIČOVÁ 1 Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacognosy and Botany, Kalinčiakova 8, SK-832 32 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] 2 Department of Botany, Moravian Museum, Zelný trh 6, CZ-659 37 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] 3 Via Martiri di via Fani 22, I-61024 Mombaroccio, Italy; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, Zemědělská 3, CZ-613 00 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] 5 Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Botany, Révová 39, SK-811 02 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] Ďuriška O., Antonín V., Para R., Tomšovský M., Jančovičová S. (2017): Taxonomy, ecology and distribution of Melanoleuca strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe. – Czech Mycol. 69(1): 15–30. Melanoleuca strictipes (P. Karst.) Métrod, a species characterised by whitish colours and macrocystidia in the hymenium, has for years been identified as several different species. Based on morphological studies of 61 specimens from eight countries and a phylogenetic analysis of ITS se- quences, including type material of M. subalpina and M. substrictipes var. sarcophyllum, we confirm conspecificity of these specimens and their identity as M. strictipes. The lectotype of this species is designated here. The morphological and ecological characteristics of this species are presented. Key words: taxonomy, phylogeny, M. -

Sporeprint, Spring 2015

LONG ISLAND MYCOLOGICAL CLUB http://limyco.org Available in full color on our website VOLUME 23, NUMBER 1, SPRING, 2015 FINDINGS AFIELD THE SEASON’S BOUNTY: 2015 Once again, Morels eluded us completely, so we have now failed to find any Black Morels at our usual collecting spot since 2011, and only a few singleton Yellow Morels that popped up here and there, except for one lucky member of the public who found thirty in Freeport under an old Cherry tree. We may have to ven- ture off-island in the future if we wish to collect Morels. Foray chair Dennis Aita of the NY Mycological Society informed me that their Morel season was lackluster, but there were oases of plenty, as wit- nessed by our webmaster Dale’s unexpected bonanza of Yellow Mo- rels on May 17 in Ulster County.(See LI Sporeprint Summer 2014.) Mean temperatures were below normal Jan thru March, and the Hygrophorus amygdalinus consequent slow soil warming delayed Spring fruiting of Morels somewhat. Will this year’s deep freeze, with the coldest February in Regular readers of this column eighty years, cause an even more pronounced delay or will the insu- might find it odd to find this one de- lating effect of deep snow cover ameliorate this process? It’s any- voted to a species which we have been one’s guess. collecting for some years, rather than Overall, last year was a consider- a newly encountered one. While Hy- able improvement over 2013, when dry grophorus amygdalinus (sometimes conditions forced us to cancel 18 forays; under a different name) is familiar to only 9, half as many, were cancelled in many of us as the small gray, almond 2014 due to lack of fungi. -

Fungal Genomes Tell a Story of Ecological Adaptations

Folia Biologica et Oecologica 10: 9–17 (2014) Acta Universitatis Lodziensis Fungal genomes tell a story of ecological adaptations ANNA MUSZEWSKA Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Pawinskiego 5A, 02-106 Warsaw, Poland E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT One genome enables a fungus to have various lifestyles and strategies depending on environmental conditions and in the presence of specific counterparts. The nature of their interactions with other living and abiotic elements is a consequence of their osmotrophism. The ability to degrade complex compounds and especially plant biomass makes them a key component of the global carbon circulation cycle. Since the first fungal genomic sequence was published in 1996 mycology has benefited from the technolgical progress. The available data create an unprecedented opportunity to perform massive comparative studies with complex study design variants targeted at all cellular processes. KEY WORDS: fungal genomics, osmotroph, pathogenic fungi, mycorrhiza, symbiotic fungi, HGT Fungal ecology is a consequence of osmotrophy Fungi play a pivotal role both in encountered as leaf endosymbionts industry and human health (Fisher et al. (Spatafora et al. 2007). Since fungi are 2012). They are involved in biomass involved in complex relationships with degradation, plant and animal infections, other organisms, their ecological fermentation and chemical industry etc. repertoire is reflected in their genomes. They can be present in the form of The nature of their interactions with other resting spores, motile spores, amebae (in organisms and environment is defined by Cryptomycota, Blastocladiomycota, their osmotrophic lifestyle. Nutrient Chytrydiomycota), hyphae or fruiting acquisition and communication with bodies. The same fungal species symbionts and hosts are mediated by depending on environmental conditions secreted molecules. -

Tricholoma (Fr.) Staude in the Aegean Region of Turkey

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2019) 43: 817-830 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1812-52 Tricholoma (Fr.) Staude in the Aegean region of Turkey İsmail ŞEN*, Hakan ALLI Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Muğla, Turkey Received: 24.12.2018 Accepted/Published Online: 30.07.2019 Final Version: 21.11.2019 Abstract: The Tricholoma biodiversity of the Aegean region of Turkey has been determined and reported in this study. As a consequence of field and laboratory studies, 31 Tricholoma species have been identified, and five of them (T. filamentosum, T. frondosae, T. quercetorum, T. rufenum, and T. sudum) have been reported for the first time from Turkey. The identification key of the determined taxa is given with this study. Key words: Tricholoma, biodiversity, identification key, Aegean region, Turkey 1. Introduction & Intini (this species, called “sedir mantarı”, is collected by Tricholoma (Fr.) Staude is one of the classic genera of local people for both its gastronomic and financial value) Agaricales, and more than 1200 members of this genus and T. virgatum var. fulvoumbonatum E. Sesli, Contu & were globally recorded in Index Fungorum to date (www. Vizzini (Intini et al., 2003; Vizzini et al., 2015). Additionally, indexfungorum.org, access date 23 April 2018), but many Heilmann-Clausen et al. (2017) described Tricholoma of them are placed in other genera such as Lepista (Fr.) ilkkae Mort. Chr., Heilm.-Claus., Ryman & N. Bergius as W.G. Sm., Melanoleuca Pat., and Lyophyllum P. Karst. a new species and they reported that this species grows in (Christensen and Heilmann-Clausen, 2013).