Topaza Pyra) (Apodiformes: Trochilidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topazes and Hermits

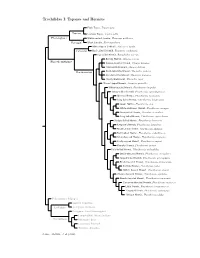

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Colombia Mega II 1St – 30Th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report

Colombia Mega II 1st – 30th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report Black Manakin by Trevor Ellery Trip Report compiled by tour leader: Trevor Ellery Trip Report – RBL Colombia - Mega II 2016 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Top ten birds of the trip as voted for by the Participants: 1. Ocellated Tapaculo 6. Blue-and-yellow Macaw 2. Rainbow-bearded Thornbill 7. Red-ruffed Fruitcrow 3. Multicolored Tanager 8. Sungrebe 4. Fiery Topaz 9. Buffy Helmetcrest 5. Sword-billed Hummingbird 10. White-capped Dipper Tour Summary This was one again a fantastic trip across the length and breadth of the world’s birdiest nation. Highlights were many and included everything from the flashy Fiery Topazes and Guianan Cock-of- the-Rocks of the Mitu lowlands to the spectacular Rainbow-bearded Thornbills and Buffy Helmetcrests of the windswept highlands. In between, we visited just about every type of habitat that it is possible to bird in Colombia and shared many special moments: the diminutive Lanceolated Monklet that perched above us as we sheltered from the rain at the Piha Reserve, the showy Ochre-breasted Antpitta we stumbled across at an antswarm at Las Tangaras Reserve, the Ocellated Tapaculo (voted bird of the trip) that paraded in front of us at Rio Blanco, and the male Vermilion Cardinal, in all his crimson glory, that we enjoyed in the Guajira desert on the final morning of the trip. If you like seeing lots of birds, lots of specialities, lots of endemics and enjoy birding in some of the most stunning scenery on earth, then this trip is pretty unbeatable. -

![Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/downloaded-from-birdtree-org-48-to-take-into-account-phylogenetic-uncertainty-in-the-comparative-analyses-67-245125.webp)

Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distribution of iridescent colours in Open Peer-Review hummingbird communities results Open Data from the interplay between Open Code selection for camouflage and communication Cite as: preprint Posted: 15th November 2019 Hugo Gruson1, Marianne Elias2, Juan L. Parra3, Christine Recommender: Sébastien Lavergne Andraud4, Serge Berthier5, Claire Doutrelant1, & Doris Reviewers: Gomez1,5 XXX Correspondence: 1 [email protected] CEFE, Univ Montpellier, CNRS, Univ Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, EPHE, IRD, Montpellier, France 2 ISYEB, CNRS, MNHN, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 45 rue Buffon CP50, Paris, France 3 Grupo de Ecología y Evolución de Vertrebados, Instituto de Biología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia 4 CRC, MNHN, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, CNRS, Paris, France 5 INSP, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Paris, France This article has been peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology 1 of 33 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Identification errors between closely related, co-occurring, species may lead to misdirected social interactions such as costly interbreeding or misdirected aggression. This selects for divergence in traits involved in species identification among co-occurring species, resulting from character displacement. -

Vogelliste Venezuela

Vogelliste Venezuela Datum: www.casa-vieja-merida.com (c) Beobachtungstage: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Birdlist VENEZUELA copyrightBeobachtungsgebiete: Henri Pittier Azulita / Catatumbo La Altamira St Domingo Paramo Los Llanos Caura Sierra de Imataca Sierra de Lema + Gran Sabana Sucre Berge und Kueste Transfers Andere - gesehen gesehen an wieviel Tagen TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae - Steißhühner 0 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius Gelbbrusttinamu 0 2 Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei Bergtinamu 0 3 Gray Tinamou Tinamus tao Tao 0 4 Great Tinamou Tinamus major Großtinamu x 0 5 White-throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus Weißkehltinamu 0 6 Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus Grautinamu x x 0 7 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui Brauntinamu x x x 0 8 Tepui Tinamou Crypturellus ptaritepui Tepuitinamu by 0 9 Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus Kastanientinamu 0 10 Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulatus Wellentinamu 0 11 Gray-legged Tinamou Crypturellus duidae Graufußtinamu 0 12 Red-legged Tinamou Crypturellus erythropus Rotfußtinamu birds-venezuela.dex x 0 13 Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus Rotbrusttinamu x x x 0 14 Barred Tinamou Crypturellus casiquiare Bindentinamu 0 ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae - Entenvögel 0 15 Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta Hornwehrvogel x 0 16 Northern Screamer Chauna chavaria Weißwangen-Wehrvogel x 0 17 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata Witwenpfeifgans x 0 18 Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Rotschnabel-Pfeifgans x 0 19 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor -

GCE Biology Question Paper Unit 02

For Examiner’s Use Centre Number Candidate Number Surname Other Names Examiner’s Initials Candidate Signature Question Mark General Certificate of Education 1 Advanced Subsidiary Examination June 2012 2 3 Biology BIOL2 4 Unit 2 The variety of living organisms 5 6 Monday 21 May 2012 1.30 pm to 3.15 pm 7 8 For this paper you must have: l a ruler with millimetre measurements. 9 l a calculator. TOTAL Time allowed l 1 hour 45 minutes Instructions l Use black ink or black ball-point pen. l Fill in the boxes at the top of this page. l Answer all questions. l You must answer the questions in the spaces provided. Do not write outside the box around each page or on blank pages. l You may ask for extra paper. Extra paper must be secured to this booklet. l Do all rough work in this book. Cross through any work you do not want to be marked. Information l The maximum mark for this paper is 85. l You are expected to use a calculator, where appropriate. l The marks for questions are shown in brackets. l Quality of Written Communication will be assessed in all answers. l You will be marked on your ability to: – use good English – organise information clearly – use scientific terminology accurately. (JUN12BIOL201) WMP/Jun12/BIOL2 BIOL2 Do not write 2 outside the box Answer all questions in the spaces provided. 1 (a) Flatworms are small animals that live in water. They have no specialised gas exchange or circulatory systems. The drawing shows one type of flatworm. -

University Babeù-Bolyai) from Cluj-Napoca (Romania

Muzeul Olteniei Craiova. Oltenia. Studii i comunicri. tiinele Naturii, Tom. XXV/2009 ISSN 1454-6914 THE EXOTIC BIRDS’ COLLECTION OF THE ZOOLOGICAL MUSEUM (UNIVERSITY BABE-BOLYAI) FROM CLUJ-NAPOCA (ROMANIA) ANGELA PETRESCU, DELIA CEUCA Abstract. We present the bird collection catalogue of the world fauna from the patrimony of the Zoological Museum of Cluj (founded in 1859). The studied collection includes 221 specimens belonging to 172 species, 59 families, 18 orders. Especially, we mention a small hummingbird collection made of 45 specimens, 38 species; some endemic species, three from Brazil (Malacoptila striata, Hemithraupis ruficapilla, Paroaria dominicana) and Apteryx oweni (New Zealand). Also, the collection includes other distinguished species as: Goura victoriae, Argusianus argus grayi, Tragopan melanocephalus, Lophophorus impejanus. Keywords: catalogue, collection, exotic bird, museum, Cluj (Romania). Rezumat. Colecia de psri exotice a Muzeului Zoologic (Universitatea Babe-Bolyai) din Cluj (România). Prezentm catalogul coleciei de psri din fauna mondial din patrimoniul Muzeului de Zoologie din Cluj (infiinat în 1859). Colecia studiat; cuprinde 221 de exemplare încadrate în 172 de specii, 59 de familii, 18 ordine. Remarcm în mod deosebit o mic colecie de colibri alctuit din 45 de exemplare, 38 de specii; câteva endemite, trei din Brazilia (Malacoptila striata, Hemithraupis ruficapilla, Paroaria dominicana) i Apteryx oweni (Noua Zeeland). Colecia conine i alte specii deosebite ca: Goura victoriae, Argusianus argus grayi, Tragopan melanocephalus, Lophophorus impejanus. Cuvinte cheie: catalog, colecie, psari, fauna mondial, muzeu, Cluj (România). INTRODUCTION The Zoological Museum of Cluj belongs to the ,,Babe-Bolyai’’ University and it was founded in 1860; it was only one part of the Museum of Transylvanian Society. -

Brazil's Eastern Amazonia

The loud and impressive White Bellbird, one of the many highlights on the Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia 2017 tour (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S EASTERN AMAZONIA 8/16 – 26 AUGUST 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL This second edition of Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia was absolutely a phenomenal trip with over five hundred species recorded (514). Some adjustments happily facilitated the logistics (internal flights) a bit and we also could explore some areas around Belem this time, providing some extra good birds to our list. Our time at Amazonia National Park was good and we managed to get most of the important targets, despite the quite low bird activity noticed along the trails when we were there. Carajas National Forest on the other hand was very busy and produced an overwhelming cast of fine birds (and a Giant Armadillo!). Caxias in the end came again as good as it gets, and this time with the novelty of visiting a new site, Campo Maior, a place that reminds the lowlands from Pantanal. On this amazing tour we had the chance to enjoy the special avifauna from two important interfluvium in the Brazilian Amazon, the Madeira – Tapajos and Xingu – Tocantins; and also the specialties from a poorly covered corner in the Northeast region at Maranhão and Piauí states. Check out below the highlights from this successful adventure: Horned Screamer, Masked Duck, Chestnut- headed and Buff-browed Chachalacas, White-crested Guan, Bare-faced Curassow, King Vulture, Black-and- white and Ornate Hawk-Eagles, White and White-browed Hawks, Rufous-sided and Russet-crowned Crakes, Dark-winged Trumpeter (ssp. -

Southeastern Brazil: Best of the Atlantic Forest

SOUTHEASTERN BRAZIL: BEST OF THE ATLANTIC FOREST OCTOBER 21–NOVEMBER 5, 2018 Green-crowned Plovercrest (©Kevin J. Zimmer) LEADERS: KEVIN ZIMMER & RICARDO BARBOSA LIST COMPILED BY: KEVIN ZIMMER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SOUTHEASTERN BRAZIL: BEST OF THE ATLANTIC FOREST October 21–November 5, 2018 By Kevin Zimmer Once again, our Southeastern Brazil tour delivered the bonanza of Atlantic Forest endemics and all-around great birding that we have come to expect from this region. But no two trips are ever exactly alike, and, as is always the case, the relative success of this tour in any given year, at least as measured in total species count and number of endemics seen, comes down to weather. And as we all know, the weather isn’t what it used to be, anywhere! We actually experienced pretty typical amounts of rain this year, and although it no doubt affected our birding success to some extent, its overall impact was relatively minimal. Nonetheless, we tallied 410 species , a whopping 150 of which were regional and/or Brazilian endemics! These figures become all the more impressive when you consider that 47 of the wider ranging species not included as “endemics” in the preceding tallies are represented in southeast Brazil by distinctive subspecies endemic to the Atlantic Forest region, and that at least 15–20 of these subspecies that we recorded during our tour are likely to be elevated to separate species status in the near future. We convened in mid-morning at the hotel in São Paulo and then launched into the five- hour drive to Intervales State Park, my own personal favorite among the many great spots in southeast Brazil. -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

Placement Student's Final Report*

Placement Student’s Final Report* LAURA CANNON *Abridged from original. Contains only Scientific Report portion. SCIENTIFIC REPORT THE EFFECT OF AN ARTIFICAL FEEDER ON HUMMINGBIRD BEHAVIOUR ABSTRACT Like their fellow nectavores, Hummingbirds try to maximize the ratio of energy obtained to energy expended; they try to consume as much nectar with as little movement as they can (Feinsinger, 1978; Hainsworth & Wolf, 1972). The way in which they optimize their consumption is through their ecologically defined roles, they behave in such a way to increase their chances of obtaining food; they often match the length of their bill to the length of the flower. Montgomerie & Gass (1981) noted that Hummingbirds abundance appears to be limited by the availability of nectar. In this study the presence of the artificial feeder provides a constant supply of food while it is up, which could cause a change in the Hummingbirds behaviour for example are maurders (bare in and feed) seen to convert to trapliners (visit multiple flowers), or territorialists (defenders) to become filchers (thieves)? Artificial feeders can affect hummingbirds foraging behaviour and abundance, but despite its potential importance, few previous studies have focused on the consequences of nectar feeders giving contradictory results (Feinsinger, 1978; Sonne et al., 2015). In a study by Arizmendi et al., (2007) the presence of a nectar feeder reduced hummingbird visitation to nearby plants in their study in Mexico. However in Brockmeyer and Schaefer’s study (2012) the number of visits to the flowers around the feeder increased when the feeder was present. This studies main focus is to determine how the presence of an artificial feeder affects the hummingbird’s behaviour specifically feeding, perching and aggression. -

Taxonomic List of the Birds of Utah (Jan 2021 - 467 Species)

Taxonomic List of the Birds of Utah (Jan 2021 - 467 species) Names and order according to the 58th supplement to the American Outline Structure: Ornithologists’ Union Check-list of North American Birds ORDER (-FORMES) FAMILY (-DAE) (I) = introduced species “Utah Bird Records Committee” Subfamily (-nae) www.utahbirds.org/RecCom Genus species Common Name ANSERIFORMES Mergus serrator Red-breasted Merganser ANATIDAE Oxyura jamaicensis Ruddy Duck Dendrocygninae GALLIFORMES Dendrocygna bicolor Fulvous Whistling-Duck ODONTOPHORIDAE Anserinae Callipepla squamata Scaled Quail Anser caerulescens Snow Goose Callipepla californica California Quail Anser rossii Ross's Goose Callipepla gambelii Gambel's Quail Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose PHASIANIDAE Branta bernicla Brant Phasianinae Branta hutchinsii Cackling Goose Alectoris chukar Chukar (I) Branta canadensis Canada Goose Perdix perdix Gray Partridge (I) Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Phasianus colchicus Ring-necked Pheasant (I) Cygnus columbianus Tundra Swan Tetraoninae Anatinae Bonasa umbellus Ruffed Grouse Aix sponsa Wood Duck Centrocercus urophasianus Greater Sage-Grouse Spatula querquedula Garganey Centrocercus minimus Gunnison Sage- Grouse Spatula discors Blue-winged Teal Lagopus leucura White-tailed Ptarmigan Spatula cyanoptera Cinnamon Teal Dendragapus obscurus Dusky Grouse Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Tympanuchus phasianellus Sharp-tailed Grouse Mareca strepera Gadwall Meleagridinae Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Meleagris gallopavo Wild Turkey Mareca americana American -

Pousada Rio Roosevelt: a Provisional Avifaunal Inventory in South

Cotinga31-090608:Cotinga 6/8/2009 2:38 PM Page 23 Cotinga 31 Pousada Rio Roosevelt: a provisional avifaunal inventory in south- western Amazonian Brazil, with information on life history, new distributional data and comments on taxonomy Andrew Whittaker Received 26 November 2007; final revision accepted 16 July 2008 first published online 4 March 2009 Cotinga 31 (2009): 23–46 Apresento uma lista preliminar de aves da Pousada Rio Roosevelt situada ao sul do rio Amazonas e leste do rio Madeira, do qual o Rio Roosevelt é um dos maiores afluentes da margem direta. A localização geográfica do pousada aumenta a importância da publicação de uma lista preliminar da avifauna, uma vez que ela se situa no interflúvio Madeira / Tapajós dentro do centro de endemismo Rondônia. Recentes descobertas ornitológicas neste centro de endemismo incluem a choca-de- garganta-preta Clytoctantes atrogularis, que foi encontrada na pousada e é considerada uma espécie globalmente ameaçada. Discuto porque a realização de levantamentos de aves na Amazônia é tão difícil, mencionando sucintamente alguns avanços ornitólogos Neotropicais principalmente com relação ao conhecimento das vocalizações das espécies. Os resultados obtidos confirmaram que o rio Roosevelt é uma importante barreira biográfica para algumas de Thamnophildae, família representada por 50 espécies na Pousada Roosevelt, localidade com a maior diversidade de espécies desta família em todo o mundo. Ao todo, um total de 481 espécies de aves foi registrado durante 51 dias no campo, indicando que estudos adicionais poderão elevar esse número para além de 550 espécies. Para cada espécie registrada são fornecidos detalhes sobre sua abundância, migração, preferências de hábitat e tipo de documentação na área.