Distribution, Variation, and Taxonomy of Topaza Hummingbirds (Aves: Trochilidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin Initiative Action Plan for the Coastal Biodiversity of Anegada, British Virgin Islands

Darwin Initiative Action Plan for the Coastal Biodiversity of Anegada, British Virgin Islands Darwin Anegada BAP 2006 Page We dedicate this document to the people of Anegada; the stewards of Anegada’s biodiversity and to Raymond Walker of the BVI National Parks Trust who tragically died after a very short illness during the course of this project. This report should be cited as: McGowan A., A.C.Broderick, C.Clubbe, S.Gore, B.J.Godley, M.Hamilton, B.Lettsome, J.Smith-Abbott, N.K.Woodfield. 2006. Darwin Initiative Action Plan for the Coastal Biodiversity of Anegada, British Virgin Islands. 13 pp. Available online at: http://www.seaturtle.org/mtrg/projects/anegada/ Darwin Anegada BAP 2006 Page 2 1. Introduction It well known that Anegada has globally important biodiversity. Indeed, biodiversity is the basis for most livelihoods; supporting fisheries and leading to the attractiveness that is such a draw to visitors. Over the last three years (2003-2006), a project was undertaken on Anegada with a wide range of activities focussing towards this Biodiversity Action Plan. From the outset it was known that the island hosts a globally important coral reef system, regionally significant populations of marine turtles, is of regional importance to birds and supports globally important endemic plants. The project arose following the encouragement of Anegada community members and subsequent extensive consultation between Dr. Godley (University of Exeter) and heads of BVI Conservation and Fisheries Department (CFD) and BVI National Parks Trust (NPT) who requested that funding be sourced for a project which: 1. Allowed the coastal biodiversity of Anegada to be assessed; 2. -

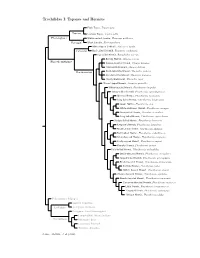

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

List of and Notes on the Birds of the Iles Des Saintes, French West Indies

LIST OF AND NOTES ON THE BIRDS OF THE ILES DES SAINTES, FRENCH WEST INDIES CHARLES VAURIE LES Saintes,a small archipelagothat lies south of Guadeloupe,has seldolnbeen visited by ornithologists.No list of its birdsseems to have beenpublished, although, to besure, 25 specieshave been mentioned froin theseislands by Noble (1916), Bond (1936, 1956), Danforth(1939), or Pinchonand Bon Saint-Come(1951). Three of thesewere recorded on doubtfulevidence and, pendingconfirmation, should be deletedfrom the list. Nineteen of the remaining 22 and an additional five were observedby me on 2-5 July 1960,when Mrs. Vaurie and I visitedthe FrenchWest Indiesfor the AmericanMuseum of Natural History. The speciesmentioned by Noble and Danforth were incorporatedin their reportson the birdsof Guadeloupe,those cited by Bondor Pinchonand Bon Saint-Comein generalworks on the birds of the West Indies. The birds reportedso far are listedbelow with a few notes. I aln grateful to James Bond for his very helpful advice, Eugene Eisenmannfor readingthe manuscript,and to the Gendarmerieof Basse Terre and Terre-de-haut for arranging our visit as there is no hotel in Les Saintes. Les Saintesare of volcanicorigin and are separatedfrom the Basse Terre in Guadeloupeby a stormychannel seven miles wide. They con- sist of two relativelylarge islandscalled Terre-de-bas and Terre-de-haut, the only islandsinhabited, and of six small islandsor islets, some of which appear to be the sites of sea-bird colonies. One of these, called La Redonde,lies only 300 metersoff Terre-de-hautbut, unfortunately, is quite inaccessibleas it risesperpendicularly out of the sea to a height of 46 metersand is poundedby huge waves that rise to nearly half its height. -

Flowers Visited by Hummingbirds in an Urban Cerrado Fragment, Mato Grosso Do Sul, Brazil

Biota Neotrop., vol. 13, no. 4 Flowers visited by hummingbirds in an urban Cerrado fragment, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil Waldemar Guimarães Barbosa-Filho1,2 & Andréa Cardoso de Araujo1 1Laboratório de Ecologia, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul – UFMS, CP 549, CEP 79070-900, Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. http://www-nt.ufms.br/ 2Corresponding author: Waldemar Guimarães Barbosa-Filho, e-mail: [email protected] BARBOSA-FILHO, W.G. & ARAUJO, A.C. Flowers visited by hummingbirds in an urban Cerrado fragment, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 13(4): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v13n4/en/ abstract?article+bn00213042013 Abstract: Hummingbirds are the main vertebrate pollinators in the Neotropics, but little is known about the interactions between hummingbirds and flowers in areas of Cerrado. This paper aims to describe the interactions between flowering plants (ornithophilous and non-ornithophilous species) and hummingbirds in an urban Cerrado remnant. For this purpose, we investigated which plant species are visited by hummingbirds, which hummingbird species occur in the area, their visiting frequency and behavior, their role as legitimate or illegitimate visitors, as well as the number of agonistic interactions among these visitors. Sampling was conducted throughout 18 months along a track located in an urban fragment of Cerrado vegetation in Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. We found 15 species of plants visited by seven species of hummingbirds. The main habit for ornithophilous species was herbaceous, with the predominance of Bromeliaceae; among non-ornithophilous most species were trees from the families Vochysiaceae and Malvaceae. -

Colombia Mega II 1St – 30Th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report

Colombia Mega II 1st – 30th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report Black Manakin by Trevor Ellery Trip Report compiled by tour leader: Trevor Ellery Trip Report – RBL Colombia - Mega II 2016 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Top ten birds of the trip as voted for by the Participants: 1. Ocellated Tapaculo 6. Blue-and-yellow Macaw 2. Rainbow-bearded Thornbill 7. Red-ruffed Fruitcrow 3. Multicolored Tanager 8. Sungrebe 4. Fiery Topaz 9. Buffy Helmetcrest 5. Sword-billed Hummingbird 10. White-capped Dipper Tour Summary This was one again a fantastic trip across the length and breadth of the world’s birdiest nation. Highlights were many and included everything from the flashy Fiery Topazes and Guianan Cock-of- the-Rocks of the Mitu lowlands to the spectacular Rainbow-bearded Thornbills and Buffy Helmetcrests of the windswept highlands. In between, we visited just about every type of habitat that it is possible to bird in Colombia and shared many special moments: the diminutive Lanceolated Monklet that perched above us as we sheltered from the rain at the Piha Reserve, the showy Ochre-breasted Antpitta we stumbled across at an antswarm at Las Tangaras Reserve, the Ocellated Tapaculo (voted bird of the trip) that paraded in front of us at Rio Blanco, and the male Vermilion Cardinal, in all his crimson glory, that we enjoyed in the Guajira desert on the final morning of the trip. If you like seeing lots of birds, lots of specialities, lots of endemics and enjoy birding in some of the most stunning scenery on earth, then this trip is pretty unbeatable. -

Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-Conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number xx76 19xx January XXXX 20212010 Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens Lisa A. Tell, Jenny A. Hazlehurst, Ruta R. Bandivadekar, Jennifer C. Brown, Austin R. Spence, Donald R. Powers, Dalen W. Agnew, Leslie W. Woods, and Andrew Engilis, Jr. Dedications To Sandra Ogletree, who was an exceptional friend and colleague. Her love for family, friends, and birds inspired us all. May her smile and laughter leave a lasting impression of time spent with her and an indelible footprint in our hearts. To my parents, sister, husband, and children. Thank you for all of your love and unconditional support. To my friends and mentors, Drs. Mitchell Bush, Scott Citino, John Pascoe and Bill Lasley. Thank you for your endless encouragement and for always believing in me. ~ Lisa A. Tell Front cover: Photographic images illustrating various aspects of hummingbird research. Images provided courtesy of Don M. Preisler with the exception of the top right image (courtesy of Dr. Lynda Goff). SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS Museum of Texas Tech University Number 76 Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare- conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens Lisa A. Tell, Jenny A. Hazlehurst, Ruta R. Bandivadekar, Jennifer C. Brown, Austin R. Spence, Donald R. Powers, Dalen W. Agnew, Leslie W. Woods, and Andrew Engilis, Jr. Layout and Design: Lisa Bradley Cover Design: Lisa A. Tell and Don M. Preisler Production Editor: Lisa Bradley Copyright 2021, Museum of Texas Tech University This publication is available free of charge in PDF format from the website of the Natural Sciences Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University (www.depts.ttu.edu/nsrl). -

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

THE J OURNAL OF CARIBBEAN ORNITHOLOGY SOCIETY FOR THE C ONSERVATION AND S TUDY OF C ARIBBEAN B IRDS S OCIEDAD PARA LA C ONSERVACIÓN Y E STUDIO DE LAS A VES C ARIBEÑAS ASSOCIATION POUR LA C ONSERVATION ET L’ E TUDE DES O ISEAUX DE LA C ARAÏBE 2005 Vol. 18, No. 1 (ISSN 1527-7151) Formerly EL P ITIRRE CONTENTS RECUPERACIÓN DE A VES M IGRATORIAS N EÁRTICAS DEL O RDEN A NSERIFORMES EN C UBA . Pedro Blanco y Bárbara Sánchez ………………....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INVENTARIO DE LA A VIFAUNA DE T OPES DE C OLLANTES , S ANCTI S PÍRITUS , C UBA . Bárbara Sánchez ……..................... 7 NUEVO R EGISTRO Y C OMENTARIOS A DICIONALES S OBRE LA A VOCETA ( RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA ) EN C UBA . Omar Labrada, Pedro Blanco, Elizabet S. Delgado, y Jarreton P. Rivero............................................................................... 13 AVES DE C AYO C ARENAS , C IÉNAGA DE B IRAMA , C UBA . Omar Labrada y Gabriel Cisneros ……………........................ 16 FORAGING B EHAVIOR OF T WO T YRANT F LYCATCHERS IN T RINIDAD : THE G REAT K ISKADEE ( PITANGUS SULPHURATUS ) AND T ROPICAL K INGBIRD ( TYRANNUS MELANCHOLICUS ). Nadira Mathura, Shawn O´Garro, Diane Thompson, Floyd E. Hayes, and Urmila S. Nandy........................................................................................................................................ 18 APPARENT N ESTING OF S OUTHERN L APWING ON A RUBA . Steven G. Mlodinow................................................................ -

Vogelliste Venezuela

Vogelliste Venezuela Datum: www.casa-vieja-merida.com (c) Beobachtungstage: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Birdlist VENEZUELA copyrightBeobachtungsgebiete: Henri Pittier Azulita / Catatumbo La Altamira St Domingo Paramo Los Llanos Caura Sierra de Imataca Sierra de Lema + Gran Sabana Sucre Berge und Kueste Transfers Andere - gesehen gesehen an wieviel Tagen TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae - Steißhühner 0 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius Gelbbrusttinamu 0 2 Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei Bergtinamu 0 3 Gray Tinamou Tinamus tao Tao 0 4 Great Tinamou Tinamus major Großtinamu x 0 5 White-throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus Weißkehltinamu 0 6 Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus Grautinamu x x 0 7 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui Brauntinamu x x x 0 8 Tepui Tinamou Crypturellus ptaritepui Tepuitinamu by 0 9 Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus Kastanientinamu 0 10 Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulatus Wellentinamu 0 11 Gray-legged Tinamou Crypturellus duidae Graufußtinamu 0 12 Red-legged Tinamou Crypturellus erythropus Rotfußtinamu birds-venezuela.dex x 0 13 Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus Rotbrusttinamu x x x 0 14 Barred Tinamou Crypturellus casiquiare Bindentinamu 0 ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae - Entenvögel 0 15 Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta Hornwehrvogel x 0 16 Northern Screamer Chauna chavaria Weißwangen-Wehrvogel x 0 17 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata Witwenpfeifgans x 0 18 Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Rotschnabel-Pfeifgans x 0 19 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor -

GCE Biology Question Paper Unit 02

For Examiner’s Use Centre Number Candidate Number Surname Other Names Examiner’s Initials Candidate Signature Question Mark General Certificate of Education 1 Advanced Subsidiary Examination June 2012 2 3 Biology BIOL2 4 Unit 2 The variety of living organisms 5 6 Monday 21 May 2012 1.30 pm to 3.15 pm 7 8 For this paper you must have: l a ruler with millimetre measurements. 9 l a calculator. TOTAL Time allowed l 1 hour 45 minutes Instructions l Use black ink or black ball-point pen. l Fill in the boxes at the top of this page. l Answer all questions. l You must answer the questions in the spaces provided. Do not write outside the box around each page or on blank pages. l You may ask for extra paper. Extra paper must be secured to this booklet. l Do all rough work in this book. Cross through any work you do not want to be marked. Information l The maximum mark for this paper is 85. l You are expected to use a calculator, where appropriate. l The marks for questions are shown in brackets. l Quality of Written Communication will be assessed in all answers. l You will be marked on your ability to: – use good English – organise information clearly – use scientific terminology accurately. (JUN12BIOL201) WMP/Jun12/BIOL2 BIOL2 Do not write 2 outside the box Answer all questions in the spaces provided. 1 (a) Flatworms are small animals that live in water. They have no specialised gas exchange or circulatory systems. The drawing shows one type of flatworm. -

Brazil's Eastern Amazonia

The loud and impressive White Bellbird, one of the many highlights on the Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia 2017 tour (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S EASTERN AMAZONIA 8/16 – 26 AUGUST 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL This second edition of Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia was absolutely a phenomenal trip with over five hundred species recorded (514). Some adjustments happily facilitated the logistics (internal flights) a bit and we also could explore some areas around Belem this time, providing some extra good birds to our list. Our time at Amazonia National Park was good and we managed to get most of the important targets, despite the quite low bird activity noticed along the trails when we were there. Carajas National Forest on the other hand was very busy and produced an overwhelming cast of fine birds (and a Giant Armadillo!). Caxias in the end came again as good as it gets, and this time with the novelty of visiting a new site, Campo Maior, a place that reminds the lowlands from Pantanal. On this amazing tour we had the chance to enjoy the special avifauna from two important interfluvium in the Brazilian Amazon, the Madeira – Tapajos and Xingu – Tocantins; and also the specialties from a poorly covered corner in the Northeast region at Maranhão and Piauí states. Check out below the highlights from this successful adventure: Horned Screamer, Masked Duck, Chestnut- headed and Buff-browed Chachalacas, White-crested Guan, Bare-faced Curassow, King Vulture, Black-and- white and Ornate Hawk-Eagles, White and White-browed Hawks, Rufous-sided and Russet-crowned Crakes, Dark-winged Trumpeter (ssp. -

Juan Cristóbal Gundlach's Collections of Puerto Rican Birds with Special

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Zoosystematics and Evolution Jahr/Year: 2015 Band/Volume: 91 Autor(en)/Author(s): Frahnert Sylke, Roman Rafela Aguilera, Eckhoff Pascal, Wiley James W. Artikel/Article: Juan Cristóbal Gundlach’s collections of Puerto Rican birds with special regard to types 177-189 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence (CC-BY); original download https://pensoft.net/journals Zoosyst. Evol. 91 (2) 2015, 177–189 | DOI 10.3897/zse.91.5550 museum für naturkunde Juan Cristóbal Gundlach’s collections of Puerto Rican birds with special regard to types Sylke Frahnert1, Rafaela Aguilera Román2, Pascal Eckhoff1, James W. Wiley3 1 Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung, Invalidenstraße 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany 2 Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, La Habana, Cuba 3 PO Box 64, Marion Station, Maryland 21838-0064, USA http://zoobank.org/B4932E4E-5C52-427B-977F-83C42994BEB3 Corresponding author: Sylke Frahnert ([email protected]) Abstract Received 1 July 2015 The German naturalist Juan Cristóbal Gundlach (1810–1896) conducted, while a resident Accepted 3 August 2015 of Cuba, two expeditions to Puerto Rico in 1873 and 1875–6, where he explored the Published 3 September 2015 southwestern, western, and northeastern regions of this island. Gundlach made repre sentative collections of the island’s fauna, which formed the nucleus of the first natural Academic editor: history museums in Puerto Rico. When the natural history museums closed, only a few Peter Bartsch specimens were passed to other institutions, including foreign museums. None of Gund lach’s and few of his contemporaries’ specimens have survived in Puerto Rico. -

Diversity and Clade Ages of West Indian Hummingbirds and the Largest Plant Clades Dependent on Them: a 5–9 Myr Young Mutualistic System

bs_bs_banner Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2015, 114, 848–859. With 3 figures Diversity and clade ages of West Indian hummingbirds and the largest plant clades dependent on them: a 5–9 Myr young mutualistic system STEFAN ABRAHAMCZYK1,2*, DANIEL SOUTO-VILARÓS1, JIMMY A. MCGUIRE3 and SUSANNE S. RENNER1 1Department of Biology, Institute for Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Str. 67, 80638 Munich, Germany 2Department of Biology, Nees Institute of Plant Biodiversity, University of Bonn, Meckenheimer Allee 170, 53113 Bonn, Germany 3Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley, CA 94720-3160, USA Received 23 September 2014; revised 10 November 2014; accepted for publication 12 November 2014 We analysed the geographical origins and divergence times of the West Indian hummingbirds, using a large clock-dated phylogeny that included 14 of the 15 West Indian species and statistical biogeographical reconstruction. We also compiled a list of 101 West Indian plant species with hummingbird-adapted flowers (90 of them endemic) and dated the most species-rich genera or tribes, with together 41 hummingbird-dependent species, namely Cestrum (seven spp.), Charianthus (six spp.), Gesnerieae (75 species, c. 14 of them hummingbird-pollinated), Passiflora (ten species, one return to bat-pollination) and Poitea (five spp.), to relate their ages to those of the bird species. Results imply that hummingbirds colonized the West Indies at least five times, from 6.6 Mya onwards, coming from South and Central America, and that there are five pairs of sister species that originated within the region.