Yellow Topaz: from Atlanta and 15 Other Guides to the South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

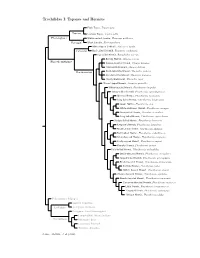

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Grosvenor Prints CATALOGUE for the ABA FAIR 2008

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books CATALOGUE FOR THE ABA FAIR 2008 Arts 1 – 5 Books & Ephemera 6 – 119 Decorative 120 – 155 Dogs 156 – 161 Historical, Social & Political 162 – 166 London 167 – 209 Modern Etchings 210 – 226 Natural History 227 – 233 Naval & Military 234 – 269 Portraits 270 – 448 Satire 449 – 602 Science, Trades & Industry 603 – 640 Sports & Pastimes 641 – 660 Foreign Topography 661 – 814 UK Topography 805 - 846 Registered in England No. 1305630 Registered Office: 2, Castle Business Village, Station Road, Hampton, Middlesex. TW12 2BX. Rainbrook Ltd. Directors: N.C. Talbot. T.D.M. Rayment. C.E. Ellis. E&OE VAT No. 217 6907 49 GROSVENOR PRINTS Catalogue of new stock released in conjunction with the ABA Fair 2008. In shop from noon 3rd June, 2008 and at Olympia opening 5th June. Established by Nigel Talbot in 1976, we have built up the United Kingdom’s largest stock of prints from the 17th to early 20th centuries. Well known for our topographical views, portraits, sporting and decorative subjects, we pride ourselves on being able to cater for almost every taste, no matter how obscure. We hope you enjoy this catalogue put together for this years’ Antiquarian Book Fair. Our largest ever catalogue contains over 800 items, many rare, interesting and unique images. We have also been lucky to purchase a very large stock of theatrical prints from the Estate of Alec Clunes, a well known actor, dealer and collector from the 1950’s and 60’s. -

Leading Manufacturers of the Deep South and Their Mill Towns During the Civil War Era

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2020 Dreams of Industrial Utopias: Leading Manufacturers of the Deep South and their Mill Towns during the Civil War Era Francis Michael Curran West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Curran, Francis Michael, "Dreams of Industrial Utopias: Leading Manufacturers of the Deep South and their Mill Towns during the Civil War Era" (2020). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7552. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7552 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dreams of Industrial Utopias: Leading Manufacturers of the Deep South and their Mill Towns during the Civil War Era Francis M. Curran Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Jason Phillips, Ph.D., Chair Brian Luskey, Ph.D. -

WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, URBAN GROWTH, and TECHNOLOGICAL SOLUTIONS in POST-WORLD WAR II ATLANTA a Dissertation

POLICY DROUGHT: WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, URBAN GROWTH, AND TECHNOLOGICAL SOLUTIONS IN POST-WORLD WAR II ATLANTA A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty by Eric M. Hardy In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in History and Sociology of Technology and Science Georgia Institute of Technology December 2011 Copyright © Eric M. Hardy 2011 POLICY DROUGHT: WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, URBAN GROWTH, AND TECHNOLOGICAL SOLUTIONS IN POST-WORLD WAR II ATLANTA Approved by: Dr. Steven Usselman, Advisor Dr. Gregory Nobles School of History, Technology School of History, Technology & Society & Society Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Ronald Bayor Dr. Martin Melosi School of History, Technolgy Department of History & Society University of Houston Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Douglas Flamming Date Approved: October 27, 2011 School of History, Technology & Society Georgia Institute of Technology For my girls, Lee and Simone ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although completing a dissertation is certainly a cause for celebration it should also a humbling experience. Rare is the young scholar that is so self-possessed and whose work is so intellectually mature that he or she did not benefit from a multitude of helping hands. My debts are indeed many, and it is with the utmost sincerity that I hope that I can repay those who have so generously invested their time and energy in me. Steve Usselman‘s contributions to my intellectual development are incalculable. I vividly recall a seminar session during my first semester at Georgia Tech when I began to think out loud about some of the implications of David Landes‘s magnum opus The Unbound Prometheus. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Conclave Opens Tuesday Herman's Blues Set Off Spring Dances

• 'By the Students, 7 he South~ s 'Best For the S tudents College ~ewspaper t Z-178 Wuhington and Le~ University Semi-Weekly LEXINGTON, VIRGINIA, APRIL 19, 1940 NUMBER 51 VOL.XLill FRIDAY, Delegations Completed; Herman's Blues Set Off Conclave Opens Tuesday Spring Dances Tonight * 1-F Sing Finals Faculty Requires Attendance ·------------------------ Combined With At Two of Three Sessions New Collegian By AL FLEISHMAN tlon will be able to vote. tor under Swing Concert the rules adopted by the conven Has Variety With the announcement laat tion's rules committee, proxies will Here we go on what promises to night of the apportionment of the not be accepted. be the grandest fun of the year student body Into the various state Members of the credentials com Of Features as Woody Herman swings his and territorial deletraUons by mittee said that they hoped no one "Band 'lbat P lays the Blues•· to Budcly Foltz. Washington and "would be oJfended" by the plac Five short stories, four articles night In Doremus aymnasiwn. fir Lee's e I g h t b mock convention lnl of delegates and that they also and an assortment of cartoons. Ml8s Anna Mae Feacbtenberrer, Ing the opening gun of the Spring awaited only the keynote speech hoped tbat every one "would enter verse and departments make up Sweet Briar senior from Bluefield, dance set of 1940. Over a thou into the aplrit of the thlna." sand guests have swarmed to the of Congressman James Wadsworth the sprlng Lssue of the SOuthern w. va., and BIUy Buxton. -

94.1 the Wolf's Second Annual Songwriter Fest Saturday March

For Immediate Release Contact: Cindy DeBardelaben March 7, 2017 Bennett Doyle Office: (901) 384-5900 [email protected] [email protected] 94.1 The Wolf’s Second Annual Songwriter Fest Saturday March 11th Hear the Stories behind #1 Hits on Country Radio Memphis, TN March 7, 2017- 94.1 The Wolf and BMI present the second annual 94.1 The Wolf Songwriter Fest at The Halloran Centre at The Orpheum this Saturday night March 11, 2017 sponsored by Memphis Area Honda Dealers. Hear the stories behind the music from the songwriters themselves in an intimate acoustic performance from hit songwriters Casey Beathard (“Like Jesus Does”, “Like A Wrecking Ball”, Eric Church, “No Shoes No Shirt No Problems”, “Don’t Blink”, Kenny Chesney), Barry Dean (“Moving Oleta” Reba McEntire, “Pontoon” Little Big Town) Sarah Buxton (“Stupid Boy” Keith Urban, co-writer on“Prizefighter” Trisha Yearwood/Kelly Clarkson “Sun Daze” Florida Georgia Line and nominated for a Prime Time Emmy Award for her music on the hit TV show “Nashville”). Country music’s hit song writers take the stage to talk about and perform their hit singles before a limited audience. These artists have written or co-written, produced and played alongside some of country music’s biggest stars like Carrie Underwood, George Strait, Kenny Chesney, Reba McEntire, Keith Urban and Eric Church, to name a few! The story-telling will be just as exciting as hearing the music live on the state-of-the- art stage, and a 361-seat theatre. The festivities begin this Saturday night, March 11th at 7pm. -

If There's a Pedigree for a Modern Country Music Star, Then Angaleena

If there’s a pedigree for a modern country music star, then Angaleena Presley fits all of the criteria: a coal miner’s daughter; native of Beauty, Kentucky; a direct descendent of the original feuding McCoys; a one-time single mother; a graduate of both the school of hard knocks and college; a former cashier at both Wal-Mart and Winn-Dixie. Perhaps best of all the member of Platinum-selling Pistol Annies (with Miranda Lambert and Ashley Monroe) says she “doesn’t know how to not tell the truth.” That truth shines through on her much-anticipated debut album, American Middle Class, which she co-produced with Jordan Powell. Yet this is not only the kind of truth that country music has always been known for—American Middle Class takes it a step further by not only being a revealing memoir of Presley’s colorful experiences but also a powerful look at contemporary rural American life. “I have lived every minute on this record. My mama ain’t none too happy about me spreading my business around but I have to do it,” Presley says. “It’s the experience of my life from birth to now.” Yet the specificity of the album’s twelve gems only makes it more universal. While zooming in on the details of her own life, Presley exposes themes to which everyone can relate. The album explores everything from a terrible economy to unexpected pregnancies to drug abuse in tightly written songs that transcend the specific and become tales of our shared experiences. “I think a good song is one where people listen to a very personal story and think ‘That’s my story, too,’” Presley says. -

![1940-09-25 [P 10]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7490/1940-09-25-p-10-767490.webp)

1940-09-25 [P 10]

ten ... husband's saber ] tfiss Jane Iredell Jones for the first 7 The cake was Marries Lieut. Clarke embossed with t, roses and valley FIREMEN DEFEAT lilies, caught?31 In Military Ceremony tiny doves. "Ith In the house RTS TO 1 white chrys,mv O from Page mums were ST SPOFFORD, 2 (Continued Six) arranged. Mrs. Jones Vilen Jones, and was met at the wore to her daught. In Seventh To wedding a gown of Will Sandlin Triples and his best white lace Cape Fear Loop iltar by the bridegroom 111 DODGERS TRIUMPH a corsage of orchids. Break Tie And Even Play Elliott M. Amlck, of Fort Ben- Hold nan, Mrs. William Banquet Tonight Latimer. 0f teu- Title Series was In ting. The bride’s stately beauty ton, great aunt 5-4 0f the bride OVER GIANTS, and managers enhanced the richness of her a of Officials, players by gown rare old lace in Fear Baseball asso- ivory. Her of the Cape A triple by Dave Sandlin in the ivedding gown which was worn by flowers were At Least will hold their annual garfctS Clinches ciation sev nth and a passed ball gave the The bride’s Brooklyn ner mother on her wedding day. book was kept bv it session at Henry Kirk- 2 1 over With Five- banquet Firemen a close to victory Die satin dress was made Perry Gordy and Tie For Second the sound tonight deep Ivory assisting l"' ham’s place on the Spofford Spinners in the second ing were Misses in empire lines with bertha of honi- Elizabeth and Run In Fifth at 8 o’clock. -

ACC Awards Come to Town Country's Big Bang

December 1, 2014, Issue 425 ACC Awards Come To Town Cumulus, FOX-TV and Dick Clark Productions partnered in June for the first American Country Countdown Awards (Break- ing News 6/12), which will air live from Nashville Dec. 15. The ACCAs are part of the continued expansion of Cumulus’ Nash entertainment brand, and Country Aircheck caught up with Cu- mulus EVP/Content & Programming and Executive Producer John Dickey on the vision and his expectations. CA: There doesn’t seem to be a shortage of awards shows, so what was attractive about doing one? JD: This would’ve been the American Country Awards’ fifth year on FOX and obviously we’re coming up on the 50th for both the ACM and CMA shows. That’s a long, rich history of awards shows in our space and we’re not adding to that. We’re simply replacing the American Country Awards with a concept that Cumulus, Dick Clark and FOX believe will be more successful, have a lot Razing The Roof: No Shave November winners celebrate at more staying power and mean something to Nashville’s The Row Monday night during the annual NSN4SKJ country fans and artists. We’re just excited Beard Bash. Pictured (l-r) are Team Beard For My Horses that it came together successfully this quickly. John Dickey (BMLG) members Dave Kelly, Garrett Hill and Alex Heddle, Nash was always envisioned to have a Beard of the Year winner George Briner, Chairman of the network-televised awards show and this won’t Beard Dave Haywood, Team Curb’s Lori Hartigan and Ryan be the only project we take there. -

)" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> """ -L «Vie»«./R Oin>)

3rd Congressional District Jack Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPAR ( ML: NT OF.THC JNT£RJOR STATE: (Julyl9o9> NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Georgia COUNTV.- NATIONAL R£G/STER OF HISTORIC PLACES Troup INVENTORY - NOMINATION FOSM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries ~ complete applicable- sections) JL NAME ' : ' • '•-''''•. ' '-••' '•. "•". •.•.'^«.V-:/-: ""\; : -"- •' ! COMMON; • • 1 Beilevue \\l^^^// j ANO- O« HiSTORlC: 1 Former homo of Benjamin'' Harvey Hill |2. LOCATION '-.'•..-. : .' ' • -•• •'•;•:••:: . :. V..;: .•.'•• i [ 204 Ben Hill Street CtTV OR TOWN; . LaGranqe jSTArt: j coot- COUNTY-, | CODE I Gaoraia 13 TroL[p 235 (.3. CLASSiflCATiCb; •'-•''•' ; ; . : V^ STATUS ACCESSIBLE «/X | CATEGORY OWNERSHIP J (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District £5 Building O Public Public Acquisition: 2£ Occupied YcS: , , . , KB R«s*rietpd ° D Sit* Q Structure JS Pnvow '. Q In Process D Unoccupied ^^ r-, 0 , Q Unrestricted Q Object D Soth D Soin9 Considoroci Q Preservation vvorfc in progress •— * PRES&MT USE (Check One- or More as Appropriate) LJ Aaricijltural Q (Jovernment Q P&'k Q Transportation D Comments Pj Commcrcia! O Industrial Q p^Jvata Ras.i<d<j«\ce ££ Qthat (Rpt>F.;!y <j jjj] £cucorior!ai Q Mi itary Q Religious :>£ fntertommcnt 53 Museum . Q Scientific i ?4. OWNSR OF PROPERTY • •••._;•,,: ': -: ',': -^'-> (OWNER'S N AME,: • - ( O . D LaGrange Woman's Club Charitable Trust . ._ . Q STREET AND NUMBER; in 204 Ben Kill Street j H- CITY OR TOWN: ' STA1•E: '. COOE [ LaGrar.ge G<=jorgia ._., .13 |S. LOCATjCN Cr LEGAL DESCRIPTION • • ;;. •: • ,".:'•-• ••;;;; "C'-v . • ••• -•.•-.-• •• • • !COk*RTHOUSE. HCG1STSY OF DEEDS. ETC: n 01 Trouo Countv Courthouse • ' n c; STREET AND NUMBER: 118 Rid ley Avenge i ,'CiTY OR TOWN: • JSTAI •e CODE 1 . -

The Politics of Conservation in Cumberland Island, Georgia

OLD BUILDINGS AND THE NEW WILDERNESS: THE POLITICS OF CONSERVATION IN CUMBERLAND ISLAND, GEORGIA By KERRY GATHERS (Under the Direction of Josh Barkan) ABSTRACT This thesis examines the projects of wilderness conservation and historic preservation as they interact to shape the landscape of Cumberland Island National Seashore on the Georgia coast. The National Park Service is obligated to protect both wilderness and historic resources, but when the two coexist they expose an ideological and functional divide between celebrating a place supposedly free from material human impacts and perpetuating human impacts deemed historically significant. The politics of balancing wilderness and human history on Cumberland Island are investigated through the analysis of interviews, legislative texts, and federal wilderness and historic preservation law. It is suggested that while federal laws accommodate the overlapping operation of both projects, funding deficiencies and entrenched assumptions about public access defining the social value of historic sites make this balance politically unstable. INDEX WORDS: wilderness, rewilding, historic preservation, national parks, conservation politics, social construction of place, environmental discourse OLD BUILDINGS AND THE NEW WILDERNESS: THE POLITICS OF CONSERVATION IN CUMBERLAND ISLAND, GEORGIA by KERRY GATHERS B.A., THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2011 © 2011 Kerry Gathers All Rights Reserved OLD BUILDINGS AND THE NEW WILDERNESS: THE POLITICS OF CONSERVATION IN CUMBERLAND ISLAND, GEORGIA by KERRY GATHERS Major Professor: JOSH BARKAN Committee: STEVE HOLLOWAY HILDA KURTZ Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the dedicated people working, all in their own ways, to keep Cumberland Island such a special place.