SJ Crane and the Baseball Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITY's Il 601 Ip» LIMB AID 111! Sill HI MB

CALKVDAB. gun rises at 7:00 a. m. gun sett at 4:36 p. m. Lantern* must be lighted 5:36 Im easing cloudiness tonight; SUB- \ DAILY day aln. Max.. 59; Min.. SB. 1M9 ESS. HEW JKR8KT. SATURDAY. .NOVEMBER 28, |WM. a Ts AH TO EXTEND CITY'S il 601 iP» LIMB AID 111! Sill HI MB «« Lively Debate, City Two Bond Issues, Aggregat I Frederick Gray's Death Fol- Borough Fathers, by Beaola- Fathers Allow $800 for ing $46,000, Are fold at When the ordinance providing for lows That ol His Brother tioif, Object to Somerset1* Fixing Up Headquarters. Harry Ullman. a dry goods dealer During the adjourned meeting or the opening of Kensington arenoe. $1,516.16 Premium. living on West Third strew, can cor- from Prospect avenue to Park are- a Month Ago. the Common Council, last night, j Taxing Methods. oborate Shakespeare in bis assertion short recess was taken for the pur- IB. MV«ATT'8 OPPOSITION. nue and Randolph road, was called that "when misfortunes come, they iip on Its third reading at the meet- EIGHTEEN IUI>I>KRK IX pose of conferring with District Su- come not single spies bat in battal- BOTH VICTIMS OF TYPHOIU. perintendent Gettings and Local Sn THKIIt U.VGIAGK I NfXJll VOCAL Ing of the Common Council, last ions." He was to have appeared In nerintendent George Luhr. of the P. "hJrd Ward Member Prevent* Too night, by Mr. Gloak, some of the York. the city court, this morning, to an- S. C. relative to trolley matters. T*n- members. -

Spalding's Official Base Ball Guide, 1910

Library of Congress Spalding's official base ball guide, 1910 SPALDING'S OFFICIAL BASE BALL GUIDE 1910 ,3I ^, Spalding's Athletic Library - FREDERICK R. TOOMBS A well known authority on skating, rowing. boxing, racquets, and other athletic sports; was sporting editor of American Press Asso- ciation, New York; dramatic editor; is a law- yer and has served several terms as a member of Assembly of the Legislature of the State of New York; has written several novels and historical works. R. L. WELCH A resident of Chicago; the popularity of indoor base ball is chiefly due to his efforts; a player himself of no mean ability; a first- class organizer; he has followed the game of indoor base ball from its inception. DR. HENRY S. ANDERSON Has been connected with Yale University for years and is a recognized authority on gymnastics; is admitted to be one of the lead- ing authorities in America on gymnastic sub- jects; is the author of many books on physical training. CHARLES M. DANIELS Just the man to write an authoritative book on swimming; the fastest swimmer the world has ever known; member New York Athletic Club swimming team and an Olym- pic champion at Athens in 1906 and London, 1908. In his book on Swimming, Champion Daniels describes just the methods one must use to become an expert swimmer. GUSTAVE BOJUS Mr. Bojus is most thoroughly qualified to write intelligently on all subjects pertaining to gymnastics and athletics; in his day one of America's most famous amateur athletes; has competed Spalding's official base ball guide, 1910 http://www.loc.gov/resource/spalding.00155 Library of Congress successfully in gymnastics and many other sports for the New York Turn Verein; for twenty years he has been prom- inent in teaching gymnastics and athletics; was responsible for the famous gymnastic championship teams of Columbia University; now with the Jersey City high schools. -

Base Ball, Trap Shooting and General Sports

•x ^iw^^<KgK«^trat..:^^ BASE BALL, TRAP SHOOTING AND GENERAL SPORTS. Volume 45 No. 3- Philadelphia, April I, 1905. Price, Five Cents. THE EMPIRE STATE THE NATIONALS. 99 THE TITLE OF A JUST STARTED SUCH IS NOW THE TITLE OF THE NEW YORK LEAGUE. WASHINGTON^ Six Towns in the Central Part of By Popular Vote the Washington the State in the Circuit An Or Club is Directed to Discard the ganization Effected, Constitution Hoodoo Title, Senators, and Re Adopted and Directors Chosen. sume the Time-Honored Name. SPECIAL TO SPORTING LIFE. SPECIAL TO SPORTING LIFB. Syracuse, N. Y., March 28. The new Washington, D. C., March 29. Hereafter baseball combination, to include thriving the Washington base ball team will be towns iu Central New York, has been known as "the Nationals." The committee christened the Empire State of local newspaper men ap League, its name being de pointed to select a name for cided at a meeting of the the reorganized Washington league, held on March. 19 Base Ball Club to take the in the Empire House this place of the hoodoo nick city. Those present were name, "Senators," held its George H. Geer, proxy for first meeting Friday after Charles H. Knapp, of Au noon and decided to call the burn, Mr. Knapp being pre new club "National," after vented by illness from at the once famous National tending; F. C. Landgraf Club of this city, that once and M. T. Roche, Cortland; played on the lot back of Robert L. Utley, J. H. Put- the White House. The com naui and Charles R. -

Kenna Record, 07-15-1921 Mr

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Kenna Record, 1910-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 7-15-1921 Kenna Record, 07-15-1921 Mr. and Mrs. A. C. White Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/kenna_news Recommended Citation Mr. and Mrs. A. C. White. "Kenna Record, 07-15-1921." (1921). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/kenna_news/384 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kenna Record, 1910-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I 1 1 J I F7 if?1 3 MM (P (M) H) v- P tLJs Lj U 3 iu - M iJ) VOL. 16 KENNA, ROOSEVELT COUNTY, NEW MEXICO, FRIDAY, JULY 15, 1921 NOi 17 ffleBaflESE P83.e07.000 KATHERINE BUTTERFIELD MARKET REPORT Tires and Tubes Accessories L. Boots and Patching and Supplies GOLD INCREASE Grnln. Wlifiat unil coin prices declined during the week. The only advance wan on tltu Phone 42 kUtli in:luMiced by good export business CONTRACTION OF CURREN-C- and reports of drouth In Kurope and Argentine. At the close wheat crop CAUSES REDUCTION Indicate damage. Export demand alow. Country offerlnRS liberal. First P. & R. GARAGE OF LOANS AND car new wheat on Chicago market July BILLS 1st sold at Sl.il3 4, graded No. 2 mixed, test weight (W. Corn crop reports gen- erally favorable; total crop estimated at El Ida, New Mexico 8.01)0,000 bushels. -

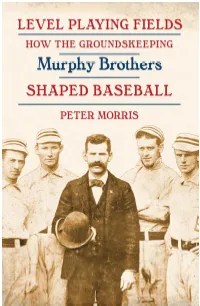

Level Playing Fields

Level Playing Fields LEVEL PLAYING FIELDS HOW THE GROUNDSKEEPING Murphy Brothers SHAPED BASEBALL PETER MORRIS UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS LINCOLN & LONDON © 2007 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska ¶ All rights reserved ¶ Manufactured in the United States of America ¶ ¶ Library of Congress Cata- loging-in-Publication Data ¶ Li- brary of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data ¶ Morris, Peter, 1962– ¶ Level playing fields: how the groundskeeping Murphy brothers shaped baseball / Peter Morris. ¶ p. cm. ¶ Includes bibliographical references and index. ¶ isbn-13: 978-0-8032-1110-0 (cloth: alk. pa- per) ¶ isbn-10: 0-8032-1110-4 (cloth: alk. paper) ¶ 1. Baseball fields— History. 2. Baseball—History. 3. Baseball fields—United States— Maintenance and repair. 4. Baseball fields—Design and construction. I. Title. ¶ gv879.5.m67 2007 796.357Ј06Ј873—dc22 2006025561 Set in Minion and Tanglewood Tales by Bob Reitz. Designed by R. W. Boeche. To my sisters Corinne and Joy and my brother Douglas Contents List of Illustrations viii Acknowledgments ix Introduction The Dirt beneath the Fingernails xi 1. Invisible Men 1 2. The Pursuit of Pleasures under Diffi culties 15 3. Inside Baseball 33 4. Who’ll Stop the Rain? 48 5. A Diamond Situated in a River Bottom 60 6. Tom Murphy’s Crime 64 7. Return to Exposition Park 71 8. No Suitable Ground on the Island 77 9. John Murphy of the Polo Grounds 89 10. Marlin Springs 101 11. The Later Years 107 12. The Murphys’ Legacy 110 Epilogue 123 Afterword: Cold Cases 141 Notes 153 Selected Bibliography 171 Index 179 Illustrations following page 88 1. -

Fun Facts About Colorado Baseball and Coors Field

Fun facts about Colorado Baseball and Coors Field By Roger Harris Denver has been a baseball town for many years. In 1862 the “Denvers” played at George Tebeau field, in 1887 the Philadelphia Phillies became the first big league team to play in Denver. In 1901 the Denver team was called the Bears and won 3 league titles. Then in 1917 professional baseball disappeared from Denver. Various Denver Bears teams were in Denver 1922-1932, Then Triple AAA baseball came to Denver in 1955. Many of you remember that Denver was home of the minor league Triple AAA Denver Bears for many years. What you might not know is that the Denver Bears were the Kansas City Blues from 1901-1954. They were pushed out of KC when a major American League team, the Philadelphia Athletics moved to KC. The Blues moved to Denver in 1955 and became the Denver Bears. The team mostly played at Mile High Stadium but most knew it as “Bears Stadium”. In 1985 the team changed it name to the Denver Zephyrs (named after the famous passenger train that traveled from Chicago to San Francisco through the Rockies). In 1993 the major National League Colorado Rockies expansion team came to Colorado. In 1994 the Zephyrs moved to New Orleans where they remained the Zephyrs until 2017 when they were rebranded the Baby Cakes. Kind of a takeoff on King Cakes and Marti Gras. The Baby Cakes had a unique promotion that any child born 2017 or later in Louisiana is eligible for a lifetime pass to the Baby Cakes! In 1991 Denver was awarded a National League expansion franchise that would become the Colorado Rockies. -

Rialto Gossip

LOS ANGELES HERALD: MORNING, 6 MONDAY FEBRUARY 15, 1909. DERBY CANDIDATES GET WORKOUT INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENT UPON RACING IN SANTA ANITA FEATURE TODAY ATHLETICS NEW BOXING WEIGHTS IS PROBABLE BOXING PLAN TO REVISE LA.ASCOTS WIN GOSSIP OF THE DIAMOND GARDENA DOWNS BOXING WEIGHTS RIALTO GOSSIP AGAINST UPLAND RED PERKINS BM&tf.- I have been asked several times dur- New York ' Giants, was dispelled DYAS-CLINENINE JAY DAVIDSON; ing the week for the numbers of va- when Merkle signed a contract for an- '&r&fcs£^fe rious managers of clubs in the miscel- other year with the New York club. LONDON SPORTING PAPER OPEhUNG GAME PROVES DISAS- laneous ranks, and therefore would The contract contained a handsome in- fT\ HERE will be no stake event to coupled with Mark in the straight bet- suggest that every manager send in crease in salary over last season. CATCHER LEAHY OF LOSERS STARTS feature card at ting only. Fleming surprised the book- their telephone number on a postal AGITATION the this week by winning, TROUS TO RUSTICS THERE-*- . Santa Anita owing to the fact ies and while he was held card, so that I can keep a record of So confident is John J. McGraw, man- IS INJURED that the Speed handicap is to be run at short odds to win, because he was them. The Herald will run these ager of the New York National league coupled with Mark in the straight numbers, as they NECESSITY OF REVISION UNIVER- one week from today, but two handi- bet- LOSERS have made several team, that the Giants will win the pen- caps are scheduled to give, the handi- ting only, those who were willing to UNABLE TO CONNECT changes in both the Home and Sunset nant this coming season that it is said BACKSTOP STUMBLES ADMITTED take him for the place got twice as AGAINST SALLY cap division of horses an opportunity WITH THE LEATHER numbers. -

History of Toledo Baseball (1883-2018)

History of Toledo Baseball (1883-2018) Year League W L PCT. GB Place Manager Attendance Stadium 1883 N.W.L. 56 28 .667 - - 1st* William Voltz/Charles Morton League Park 1884 A.A. 46 58 .442 27.5 8th Charles Morton 55,000 League Park/Tri-State Fairgrounds (Sat. & Sun.) 18851 W.L. 9 21 .300 NA 5th Daniel O’Leary League Park/Riverside Park (Sun.) 1886-87 Western League disbanded for two years 1888 T.S.L. 46 64 .418 30.5 8th Harry Smith/Frank Mountain/Robert Woods Presque Isle Park/Speranza Park 1889 I.L. 54 51 .568 15.0 4th Charles Morton Speranza Park 1890 A.A. 68 64 .515 20.0 4th Charles Morton 70,000 Speranza Park 1891 Toledo dropped out of American Association for one year 18922 W.L. 25 24 .510 13.5 4th Edward MacGregor 1893 Western League did not operate due to World’s Fair, Chicago 1894 W.L. 67 55 .549 4.5 2nd Dennis Long Whitestocking Park/Ewing Street Park 18953 W.L. 23 28 .451 27.5 8th Dennis Long Whitestocking Park/Ewing Street Park 1896 I.S.L. 86 46 .656 - - 1st* Frank Torreyson/Charles Strobel 45,000 Ewing Street Park/Bay View Park (Sat. & Sun.) 1897 I.S.L. 83 43 .659 - - 1st* Charles Strobel Armory Park/Bay View Park (Sat. & Sun.) 1898 I.S.L. 84 68 .553 0.5 2nd Charles Strobel Armory Park/Bay View Park (Sat. & Sun.) 1899 I.S.L. 82 58 .586 5.0 3rd (T) Charles Strobel Armory Park/Bay View Park (Sat. -

BASE BALL, BICYCLING and Yet Officially Defined

THE SPORTINGCOPYRIGHT, 1894, BY THE SPORTINO LIJZ SUB. CO. ENTERED AT PHI1A. P. O. A3 SECOND CLAS3 LIFE VOLUME 23, NO. 1. PHILADELPHIA, PA., MARCH 31, 1891. PRICE, TEN CENTS. League has been admitted to protection This is the player Mr. Stallings has under the National Agreement. been corresponding with for some time, THE SPORTING LIFE. but at last landed him. Callopy will CHANGE OF PLAN. CINCINNATI CHIPS. cover short field for Nashville. This LATE NEWS BY 1IRE. A WEEKLY JOURNAL AS TO HARRY WRIGHT. is the player who did such fine work for Devoted to Oakland last season, he having led the His Duties in His New Position Not DAVIS NOW RETURNS TO HIS ORI THE HOME PLAYERS ONE BY ONE league in base running and also near THE SOUTHERN LEAGDE ADOPTS BASE BALL, BICYCLING AND Yet Officially Defined. the top in hitting and fielding. While Harry Wright's duties as chief GINAL PROJECT, REPORTING FOR WORK. The signing of Callopy caused the THE KIFFE BALL GENERAL SPORTS AND of umpires have not been officially de- release of Truby, whom Mr. Stallings PASTIMES. finod by President Young, it is not un had signed to play short. Truby, on likely that all complaints will be turned in Winter Qnarters-Niland's receiving his release, immediately signed The Annual Meeting ol the Connecti over to him for investigation. He will And Abandons the Tri-State League Comiskey with Memphis. Published by visit the city where the umpire against The team up to date is composed of whom the charges have beon made is Idea in Favor ol His Original Plan Good Showing Panott Wants More Spies, catcher; Borchers, Lookabaugh cut League-Changes Made in the THE SPORTING LIFE PUBLISHING CO. -

Debut Year Player Hall of Fame Item Grade 1871 Doug Allison Letter

PSA/DNA Full LOA PSA/DNA Pre-Certified Not Reviewed The Jack Smalling Collection Debut Year Player Hall of Fame Item Grade 1871 Doug Allison Letter Cap Anson HOF Letter 7 Al Reach Letter Deacon White HOF Cut 8 Nicholas Young Letter 1872 Jack Remsen Letter 1874 Billy Barnie Letter Tommy Bond Cut Morgan Bulkeley HOF Cut 9 Jack Chapman Letter 1875 Fred Goldsmith Cut 1876 Foghorn Bradley Cut 1877 Jack Gleason Cut 1878 Phil Powers Letter 1879 Hick Carpenter Cut Barney Gilligan Cut Jack Glasscock Index Horace Phillips Letter 1880 Frank Bancroft Letter Ned Hanlon HOF Letter 7 Arlie Latham Index Mickey Welch HOF Index 9 Art Whitney Cut 1882 Bill Gleason Cut Jake Seymour Letter Ren Wylie Cut 1883 Cal Broughton Cut Bob Emslie Cut John Humphries Cut Joe Mulvey Letter Jim Mutrie Cut Walter Prince Cut Dupee Shaw Cut Billy Sunday Index 1884 Ed Andrews Letter Al Atkinson Index Charley Bassett Letter Frank Foreman Index Joe Gunson Cut John Kirby Letter Tom Lynch Cut Al Maul Cut Abner Powell Index Gus Schmeltz Letter Phenomenal Smith Cut Chief Zimmer Cut 1885 John Tener Cut 1886 Dan Dugdale Letter Connie Mack HOF Index Joe Murphy Cut Wilbert Robinson HOF Cut 8 Billy Shindle Cut Mike Smith Cut Farmer Vaughn Letter 1887 Jocko Fields Cut Joseph Herr Cut Jack O'Connor Cut Frank Scheibeck Cut George Tebeau Letter Gus Weyhing Cut 1888 Hugh Duffy HOF Index Frank Dwyer Cut Dummy Hoy Index Mike Kilroy Cut Phil Knell Cut Bob Leadley Letter Pete McShannic Cut Scott Stratton Letter 1889 George Bausewine Index Jack Doyle Index Jesse Duryea Cut Hank Gastright Letter -

Esearc JOURNAL

THE ase a esearc JOURNAL OMPARISONS BETWEEN athletes of to; Fourteenth Annual Historical and Statistical Review day and those of yesteryear are inevitable. In of'the Society for American Baseball Research C many respects baseball lends itself'to such as; sessments to a greater degree than any sport. This is so for at least two reasons: l;The nature of the game remains Cobb, Jackson and Applied Psychology, David Shoebotham 2 Protested Games Muddle Records, Raymond]. Gonzalez 5 essentially the same now as when itfirst was played, and Honest John Kelly, James D. Smith III 7 2;Statistical documentationofplayerachievements spans Milwaukee's Early/Teams, Ed Coen 10 bas~. more, than a century, thus providing a solid data Pitching Triple Crown, Martin C. Babicz 13 As Pete ,Rose approached - and then broke - the Researcher's Notebook, Al Kermisch 15 hallowed record for career hits held by T y Cobb, another Alabama Pitts, Joseph M. Overfield 19 flood of comparisons began taking shape. Pete was quick Dickshot's Hitting Streak, Willie Runquist 23 to say hedidn't feel he was a greater player than Cobb had A Conversation with BilLJames; Jay Feldman 26 been, but added merely that he had produced more hits. Tim McNamara, Jim Murphy 30 The two men had much in common, of cQurse.Both Change of Allegiance, HenryL. Freund, Jr. 33 were always known as flerce competitors. Each spent most Stars Put'Syracuse on Map, Lloyd Johnson 35 of his CHreer with on,e club and eventually managed that Counting Stats, New Stats, Bobby Fong 37 team. And in a touch of irony, Cobb was in his eighty; Ruth's 1920 Record Best Ever, Larry Thompson 41 Lifetime 1.000 Hitters, Charles W. -

Someohiieqiipsa

wo THE SUNDAY OREGONIAX, PORTLAND. JULY 7, 1912. IS In Gentle Art of Slamming Out a Safe One, Bringing in a Needed Run at a Game's Critical Point, No Big Leaguer Excels Joseph. Bert Tinker, the Star Shortstop of the Chicago Cuhs. Using W. E. Whiston as His QuilUwielder He Gives Some Interesting Side- lights on This Angle of the Na- tional Sport. Joseph Bert Tinker, star even a double. But It simply goes to of the Chicago Cubs, show that while nearly every other WHEN team in the league would dodge Wag first 'made his debut in big ner on account of his reputation as a league company, back In 1901. It was Dinch hitter. 'Chicago would rather sold me to Hagen's Tailors for the $3. that someone immediately took up a primarily due to the fact that he had have him than Clarke, who, while an I stayed with them a year and then collection which netted me $8.50. gained a reputation as a player, who excellent player, doesn't appeal to the started out with the J. F. Schmelzer "John Grimm, of the Portland Pacifle average fan as so much of a foe as team, representing a sporting goods Northwest League, signed me up. My was nearly always good for a safe hit in City. game's point. He could Wagner would be. house Kansas work at third for that team attracted at a critical "A man doesn't have to be a fan or "Johnny Kllng, who afterward be- the attention of the scouts for the Cubs, be depended on to smash out a hard an expert to know that no player can came a catcher in the big league, and and in the Fall of 1901 I signed, with drive in the hour of his team's most be expected to hit a ball every time he who has often been termed the peer of Chicago.