Morris Borderline Catastrophe.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACE Train Has Special Offer Incentives for Cutting S.J. Emissions Proposed

ACE train has special offer The Record, Published Wednesday, April 23, 2003 Altamont Commuter Express is offering a special deal to commuters who have never tried taking the train to work. Until the end of June, new ACE riders can get a one-week pass for free by calling (800) 411- RAIL. Commuters who call by Thursday each week can get a pass for the next week. After the trial period, those new riders who participated in the "Taste of ACE" event will be able to buy monthly passes for 50 percent off the regular price. For more information on ACE schedules and stations, go to www.acerail.com. Incentives for cutting S.J. emissions proposed By Audrey Cooper, Record Staff Writer Published Thursday, April 24, 2003 FRESNO -- Business and community leaders at a first-ever clean-air summit Wednesday unveiled a proposed plan to cut smog by offering tax incentives and government funds to industries or groups that cut emissions. The Operation Clean Air summit drew more than 400 people from around the San Joaquin Valley, which is by some standards the country's most polluted area. That pollution has been linked to climbing asthma rates, premature deaths and cancer. Operation Clean Air is a public-private organization interested in finding voluntary measures to cut the Valley's pollution. It was the brainchild of Fresno-area politicians and includes representatives of the nine-county Valley air basin. Officials said the proposed plan was only a draft and would go through several changes over the next few months. But the popular centerpiece of the plan is a proposed "Air Quality Improvement Zone," which could work similar to municipal economic-improvement zones that use various financial incentives to encourage urban redevelopment. -

Certificate of the Secretary of State I, BILL JONES, Secretary of State Of

Certificate of the Secretary of State I, BILL JONES, Secretary of State of the State of California, hereby certify: THAT the following is a full, true, and correct statement of the result of the official canvass of the returns of the November 7, 2000, Presidential General Election. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I hereunto set my hand and affix the Great Seal of California, at Sacramento, this 15th day of December, 2000. BILL JONES Secretary of State xxxi County by County Vote Results for President Al Gore George W. Howard Ralph Harry John Patrick J. Rev. William Bush Phillips Nader Browne Hagelin Buchanan M. Kenyon, Sr. DEM REP AI GRN LIB NL REF IND (W/I) Alameda 342,889 119,279 1,237 27,499 1,910 492 1,026 0 Percent 69.4% 24.2% 0.2% 5.6% 0.4% 0.0% 0.2% 0.0% Alpine 265 281 1 25 6 0 8 0 Percent 45.3% 48.0% 0.1% 4.3% 1.0% 0.0% 1.3% 0.0% Amador 5,906 8,766 24 584 81 9 94 0 Percent 38.2% 56.7% 0.1% 3.8% 0.5% 0.0% 0.7% 0.0% Butte 31,338 45,584 125 5,727 381 80 486 0 Percent 37.5% 54.5% 0.1% 6.9% 0.4% 0.0% 0.6% 0.0% Calaveras 7,093 10,599 57 863 140 16 108 0 Percent 37.6% 56.2% 0.3% 4.6% 0.8% 0.0% 0.5% 0.0% Colusa 1,745 3,629 12 151 12 3 38 0 Percent 31.3% 65.0% 0.2% 2.7% 0.2% 0.0% 0.6% 0.0% Contra Costa 224,338 141,373 346 13,067 1,290 286 778 0 Percent 58.9% 37.1% 0.0% 3.5% 0.3% 0.0% 0.2% 0.0% Del Norte 3,117 4,526 36 485 52 13 65 0 Percent 37.6% 54.6% 0.4% 5.9% 0.6% 0.1% 0.8% 0.0% El Dorado 26,220 42,045 115 3,013 334 72 337 0 Percent 36.4% 58.3% 0.1% 4.2% 0.5% 0.0% 0.5% 0.0% Fresno 95,059 117,342 207 6,541 440 126 1,120 0 Percent 43.1% 53.2% 0.0% -

Vital Statistics on Congress 2001-2002

Vital Statistics on Congress 2001-2002 Vital Statistics on Congress 2001-2002 NormanJ. Ornstein American Enterprise Institute Thomas E. Mann Brookings Institution Michael J. Malbin State University of New York at Albany The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. 2002 Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 152.00 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 172.14. To order call toll free 1-800-462.-642.0 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 2.0036 or call 1-800-862.-5801. Available in the United States from the AEI Press, do Publisher Resources Inc., 1224 Heil Quaker Blvd., P O. Box 7001, La Vergne, TN 37086-7001. To order, call toll free: 1-800-937-5557. Distributed outside the United States by arrangement with Eurospan, 3 Henrietta Street, London WC2E 8LU, England. ISBN 0-8447-4167-1 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 0-8447-4168-X (pbk.: alk. paper) 13579108642 © 2002 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. Printed in the United States ofAmerica Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Preface ............................................ -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 107 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 107 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 148 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, AUGUST 1, 2002 No. 108—Part II House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Wednesday, September 4, 2002, at 2 p.m. Senate THURSDAY, AUGUST 1, 2002 TRADE ACT OF 2002 MURKOWSKI, and WELLSTONE on bene- Finally, I would say a word of thanks Mr. BAUCUS. Mr. President, before fits for steel retirees. to the many members of the Adminis- we conclude today, I would be remiss if Finally, I, of course want to thank tration who staffed and supported this I did not thank a number of people. my partner on the Finance Committee, legislative effort, including Grant First, in the House, I want to thank Senator CHUCK GRASSLEY for being Aldonas, Faryar Shirzad, Peter David- Chairman BILL THOMAS. He and I dis- helpful throughout this process. son, John Veroneau, Heather Wingate, agree on some things—that’s for sure. Of course, to actually complete work Brenda Becker, Penny Naas, and many But we share a common goal of both on a major bill like this requires the others. expanding trade and helping workers efforts of many others. For more than I—as well as the Senate and the left behind by trade. And we share the 18 months, many staff members have country—owe you all a debt of grati- goal of getting this to the President’s made incalculable efforts to prepare tude. -

California Results from General Election Held on November 2, 2004

THE CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE FOR FEDERAL POLICY RESEARCH 419 New Jersey Avenue, SE, Washington, D.C. 20003 202-546-3700 Fax: 202-546-2390 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.calinst.org SPECIAL REPORT: California Results from General Election held on November 2, 2004 The following table shows final vote totals for California from yesterday's general election for President, U.S. Senate, House of Representatives, and the 16 statewide ballot propositions. Challenger John Kerry outpolled President George Bush by approximately 10 percentage points in California, Senator Barbara Boxer was reelected by approximately a 20-point margin, and all 51 serving Members of Congress that sought reelection won their races. The state's House delegation will continue to include 33 Democrats and 20 Republicans, with party membership unchanged in California's two open House seats -- Dan Lungren won the race to succeed retiring Rep. Doug Ose by a 27-point margin, and Jim Costa won the race to succeed Rep. Cal Dooley by 7.4 percentage points. All results are as of Wednesday morning, November 3, 2004 at 6:41 am PST, and are courtesy of the California Secretary of State's office. To view these data and data from other races -- including 100 state legislative seats -- visit http://vote2004.ss.ca.gov/ . (Data are best viewed in a proportionally spaced font, such as courier.) CANDIDATE PARTY VOTES PERCENT PRESIDENT John F. Kerry Democratic 5,427,133 54.6 * George W. Bush Republican 4,403,475 44.3 Michael Anthony Peroutka American Independent 21,057 0.2 David Cobb Green 31,679 0.3 Michael Badnarik Libertarian 39,797 0.4 Leonard Peltier Peace & Freedom 21,550 0.2 U.S. -

From the Omnibus Act of 1988 to the Trade Act of 2002

AMERICAN TRADE POLITICS: From the Omnibus Act of 1988 To The Trade Act of 2002 Kent Hughes Director, Project on America and the Global Economy Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars A paper prepared for presentation at the Congress Project/Project on America and the Global Economy seminar on “Congress and Trade Policy” at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, November 17, 2003 Kent Hughes, Project on America and the Global Economy 2 Introduction: In 1988, the Congress passed the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 with broad bipartisan support. Unlike most post-World War II trade legislation, the Omnibus Act originated with the Congress rather than with a proposal from the Administration. Despite continuing Administration objections, final passage came in 1988 by wide margins in both the House and the Senate. In addition to a comprehensive competitiveness or productivity growth strategy, the Omnibus Act included negotiating objectives and fast track authority. Under fast track procedures, the Congress agreed to an up or down vote on future trade agreements without the possibility of adding any amendments. Neither the fast track procedures nor the bill’s negotiating objectives were particularly controversial at the time. Fast track authority (for completing negotiations) lapsed on June 1, 1993. President Clinton unsuccessfully sought to renew fast track authority in 1997. He tried again in 1998 only to lose decisively in the House of Representatives. In 2001, a new Administration made securing Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), a new name for fast track, an early Administration priority. Yet despite a newly elected Republican President, George W. -

Info Sought on Power Plant Plan

Info sought on power plant plan By Tim Moran, staff writer The Modesto Bee, March 3, 2004 The proposed 1,120-megawatt Tesla Power Project near Tracy is not quite ready for prime time, according to a committee of the California Energy Commission. The committee reported late last week that it needs more information on air quality and water elements of the $600 million project. A new hearing has been scheduled for 11 a.m. April 8 at the Tracy Community Center, 300 E. 10th St. The natural gas-fired turbine power plant would be one of the largest in the state, and would be within 10 miles of a 1,100-megawatt plant already licensed by the commission but not yet operating. The Tesla project would be on 60 acres of farmland near Midway Road, southeast of Interstate 580. The site is in eastern Alameda County, near the San Joaquin County border. The plant could be operational by late 2006 if the evidence requests do not cause significant delays. Once a license is approved, the applicant has five years to build. The project is proposed by Midway Power LLC, a subsidiary of Florida Power & Light Group-FPL Energy. The commission's committee wants more testimony on ammonia and particulate air emissions from the project and the water source for cooling the plant. Like Calpine's East Altamont Energy Center, the other large power plant in the area, the Tesla project poses jurisdictional air quality issues. Both power plant sites are in Alameda County, and fall under the jurisdiction of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. -

Alabama at a Glance

ALABAMA ALABAMA AT A GLANCE ****************************** PRESIDENTIAL ****************************** Date Primaries: Tuesday, June 1 Polls Open/Close Must be open at least from 10am(ET) to 8pm (ET). Polls may open earlier or close later depending on local jurisdiction. Delegates/Method Republican Democratic 48: 27 at-large; 21 by CD Pledged: 54: 19 at-large; 35 by CD. Unpledged: 8: including 5 DNC members, and 2 members of Congress. Total: 62 Who Can Vote Open. Any voter can participate in either primary. Registered Voters 2,356,423 as of 11/02, no party registration ******************************* PAST RESULTS ****************************** Democratic Primary Gore 214,541 77%, LaRouche 15,465 6% Other 48,521 17% June 6, 2000 Turnout 278,527 Republican Primary Bush 171,077 84%, Keyes 23,394 12% Uncommitted 8,608 4% June 6, 2000 Turnout 203,079 Gen Election 2000 Bush 941,173 57%, Gore 692,611 41% Nader 18,323 1% Other 14,165, Turnout 1,666,272 Republican Primary Dole 160,097 76%, Buchanan 33,409 16%, Keyes 7,354 3%, June 4, 1996 Other 11,073 5%, Turnout 211,933 Gen Election 1996 Dole 769,044 50.1%, Clinton 662,165 43.2%, Perot 92,149 6.0%, Other 10,991, Turnout 1,534,349 1 ALABAMA ********************** CBS NEWS EXIT POLL RESULTS *********************** 6/2/92 Dem Prim Brown Clinton Uncm Total 7% 68 20 Male (49%) 9% 66 21 Female (51%) 6% 70 20 Lib (27%) 9% 76 13 Mod (48%) 7% 70 20 Cons (26%) 4% 56 31 18-29 (13%) 10% 70 16 30-44 (29%) 10% 61 24 45-59 (29%) 6% 69 21 60+ (30%) 4% 74 19 White (76%) 7% 63 24 Black (23%) 5% 86 8 Union (26%) -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may t>e from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 University of Oklahoma Graduate College The Tenuous Majority: The Effect of Two-Party Competition on the House of Representatives A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By JOHN P. -

6Housecomrosters La

IMPACT ON HOUSE COMMITTEES House Committee Changes Agriculture Democrats David R. Obey, Wis. Carrie P. Meek, Fla. Republicans John P. Murtha, Pa. David E. Price, N.C. Larry Combest, Texas — chairman Norm Dicks, Wash. Chet Edwards, Texas John A. Boehner, Ohio Bob Riley, Ala. Martin Olav Sabo, Minn. Robert E. “Bud” Cramer, Ala. Robert W. Goodlatte, Va. Mike Simpson, Idaho Steny H. Hoyer, Md. Patrick J. Kennedy, R.I. Richard W. Pombo, Calif. Doug Ose, Calif. Alan B. Mollohan, W.Va. James E. Clyburn, S.C. Nick Smith, Mich. Robin Hayes, N.C. Marcy Kaptur, Ohio Maurice D. Hinchey, N.Y. Terry Everett, Ala. Charles W. “Chip” Pickering Jr., Miss. Nancy Pelosi, Calif. Lucille Roybal-Allard, Calif. Frank D. Lucas, Okla. Timothy V. Johnson, Ill. Peter J. Visclosky, Ind. Sam Farr, Calif. Saxby Chambliss, Ga. Tom Osborne, Neb. Nita M. Lowey, N.Y. Jesse L. Jackson Jr., Ill. Jerry Moran, Kan. Mike Pence, Ind. Jose E. Serrano, N.Y. Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick, Mich. Bob Schaffer, Colo. Denny Rehberg, Mont. Rosa DeLauro, Conn. Allen Boyd, Fla. John Thune, S.D. Sam Graves, Mo. James P. Moran, Va. Chaka Fattah, Pa. Bill Jenkins, Tenn. Adam H. Putnam, Fla. John W. Olver, Mass. Steven R. Rothman, N.J. John Cooksey, La. Mark Kennedy, Minn. Ed Pastor, Ariz. Gil Gutknecht, Minn. George W. Gekas, Pa. Democrats Armed Services Republicans Charles W. Stenholm, Texas Bob Etheridge, N.C. Bob Stump, Ariz. - chairman Gary A. Condit, Calif. Leonard L. Boswell, Iowa Collin C. Peterson, Minn. David Phelps, Ill. Duncan Hunter, Calif. Jim Ryun, Kan. Cal Dooley, Calif. -

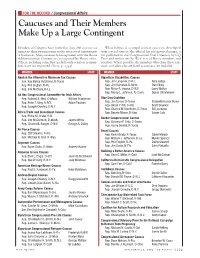

List of Caucuses

! FOR THE RECORD / Congressional Affairs Caucuses and Their Members Make Up a Large Contingent Members of Congress have formed at least 286 caucuses to What follows is a compilation of caucuses, developed represent their own priorities or the interests of constituents from several sources: the official list of registered groups, a or businesses. Many caucuses have registered with the House list published in the Congressional Staff Directory by CQ Administration Committee, as required by House rules. Press and entries on the Web sites of House members and Others, including some that include only senators as mem- senators. Where possible, the members who chair these cau- bers, have not registered. (Story, p. 2334) cuses and aides who are listed as contacts are included. MEMBER STAFF MEMBER STAFF Abolish the Alternative Minimum Tax Caucus Bipartisan Disabilities Caucus Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, R-Texas Rep. Jim Langevin, D-R.I. Amy Judge Rep. Phil English, R-Pa. Rep. Jim Ramstad, R-Minn. Dan Elling Rep. Jim McCrery, R-La. Rep. Major R. Owens, D-N.Y. Larry Walker Rep. Nancy L. Johnson, R.-Conn. Susan Christensen Ad Hoc Congressional Committee for Irish Affairs Rep. Richard E. Neal, D-Mass. William Tranghese Blue Dog Coalition Rep. Peter T. King, R-N.Y. Adam Paulson Rep. Jim Turner, D-Texas Elizabeth Hurley Burks Rep. Joseph Crowley, D-N.Y. Rep. Baron P. Hill, D-Ind. Scott Downes Rep. Charles W. Stenholm, D-Texas Ed Lorenzen Africa Trade and Investment Caucus Rep. Dennis Moore, D-Kan. Jason Cole Rep. Philip M. Crane, R-Ill. Border Congressional Caucus Rep. -

Lawyering Against Power: the Risks of Representing Vulnerable and Unpopular Communities

Seattle Journal for Social Justice Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 13 7-1-2012 Lawyering Against Power: The Risks of Representing Vulnerable and Unpopular Communities Jose ́ Padilla Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj Recommended Citation Padilla, Jose ́ (2012) "Lawyering Against Power: The Risks of Representing Vulnerable and Unpopular Communities," Seattle Journal for Social Justice: Vol. 11 : Iss. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj/vol11/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seattle Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 173 Lawyering Against Power: The Risks of Representing Vulnerable and Unpopular Communities1 José R. Padilla2 Many years ago, during a time of fundraising for the Korematsu redress work, Attorney Don Tamaki inspired me by urging me and other advocates to become involved with social justice causes because they are about family and about family healing. The coram nobis advocacy was about his Sansei generation freeing the Nisei generation before them—freeing a generation from shame and silence. It has always inspired me in the justice work that I do. Social justice lawyering, exemplified by the Korematsu and Hirabayashi cases, is political lawyering, which must address the failures of democracy. To put equality before the law demands a commitment to participation in the movement toward systemic change and to representation of the most vulnerable members of society.