Stefan Firca Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Add To), Provided That Credit Is Given to Michael Erlewine for Any Use of the Data Enclosed Here

POSTER DATA COMPILED BY MICHAEL ERLEWINE Copyright © 2003-2020 by Michael Erlewine THIS DATA IS FREE TO USE, SHARE, (AND ADD TO), PROVIDED THAT CREDIT IS GIVEN TO MICHAEL ERLEWINE FOR ANY USE OF THE DATA ENCLOSED HERE. There is no guarantee that this data is complete or without errors and typos. This is just a beginning to document this important field of study. [email protected] ------------------------------ 1967-06-18 P-1 --------- 1967-06-18 / CP010340 / CS05917 Jimi Hendrix at Monterey Pop Festival - Monterey, CA Artist: Randy Tuten Venue: Monterey Pop Festival Items: Original poster (Original artwork) Edition 1 / CP010340 / CS05917 (14 x 20) Performers: 1967-06-18: Monterey Pop Festival Jimi Hendrix ------------------------------ 1967-06-18 P --------- 1967-06-18 / CP060692 / CP060692 Monterey Pop Festival (Original Art) Notes: Original Art Artist: Randy Tuten Venue: Monterey Pop Festival Items: Original poster / CP060692 / CP060692 (14 x 20) Performers: 1967-06-18: Monterey Pop Festival Jimi Hendrix ------------------------------ FW-BG-159 1968-02-06 P-1 --------- 1968-02-06 / FW BG-159 CP007260 / CP02510 Byrds, Michael Bloomfield at Fillmore West - San Francisco, CA Private Notes: BG-CD(+BG-158) BG-OP-1-Signed-Tuten A- 50- Artist: Randy Tuten Venue: Fillmore West Promoter: Bill Graham Original Series Items: Original poster FW-BG-159 Edition 1 / CP007260 / CP02510 Description: 1 original (14 x 21-3/4) Price: 100.00 Postcard FW-BG-159 Edition 1 / CP007858 / CP03102 Description: original, postal variations, double with BG158 (7 -

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Bob Sarles Resume

Bob Sarles [email protected] (415) 305-5757 Documentary I Got A Monster Editor. True crime feature documentary. Directed by Kevin Abrams. Alpine Labs. The Nine Lives of Ozzy Osbourne Producer, editor. An A&E documentary special. Osbourne Media. Born In Chicago Co-director, Editor. Feature documentary. Shout! Factory/Out The Box Records. Mata Hari The Naked Spy Editor. Post Production Producer. Feature documentary. Red Spoke Films. BANG! The Bert Berns Story Co-director (with Brett Berns), editor. Theatrically released feature documentary. Sweet Blues: A Film About Mike Bloomfield Director, Editor. Produced by Ravin’ Films for Sony Legacy. Moon Shot Editor. Documentary series produced for Turner Original Productions and aired on TBS. Peabody Award recipient. Two Primetime Emmy nominations: editing and outstanding documentary. The Story of Fathers & Sons Editor. ABC documentary produced by Luna Productions. Unsung Editor. Documentary television series produced by A.Smith & Company for TV One. Behind The Music Producer and Editor. Documentary television series produced by VH1. Digital Divide Series Editor. PBS documentary series produced by Studio Miramar. The True Adventures of The Real Beverly Hillbillies Editor. Feature documentary. Ruckus Films. Wrestling With Satan Co-Producer, editor. Feature documentary. Wandering Eye Productions. Feed Your Head Director, editor. Documentary film produced for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Cleveland. Yo Cip! Director, Editor. Documentary short. A Ravin’ Film for Cipricious Productions. Produced by Joel Peskin. Coldplay Live! At The Fillmore Director, editor. Television series episode produced by BGP/SFX. Take Joy! The Magical World of Tasha Tudor Editor. Documentary. Aired on PBS. Spellbound Prods. Teen People Presents 21 Stars Under 21 Editor. -

Maureen O'connor Mont H.., M T He Ship Repair O'connor Discusses Her Bustness

The UCSDGuar a Unj\(~rsjt~ of Califo,·nia. ~an Dit'go VOIUIlH.' lH, NumlH'1' I:! Thlln,c1a~. Ft'IIt'ual"~ 10, ) HH:~ A 1 I acre plot "oj land t he Del Mar c()a~t has , t hr cent er of a ontn)\ers\ that \\ill Del Mar vote: lmmatr \V-ith a special llot to be held next y. The vote w111 ine whether or not A park or a parking lot land, currently owned the Waterworks Co., ould be purchased by the it\- of Del Mar as the final stallment in it. <.;e nes of stal parks. If the voters rn down the purchase,the evelop(·r.... \\ til go ahead 'th construction of a re .... I<iUrant on the sIte, as \\t'll as ;\ maSSIve, t\\·o .... tore\· parking structure USI ;icro ... s Coast Hh d. TIlt' campaIgn for the purc.ha'-t' of \\ hat has Ix: mw 10 be known as Powt'rhouse Park has ained the \()Clferous upport of Barve) ShapIro, mayor of Del ~1ar and professor of Anesthe...,lOlogy t l lC. [) !\ledical School. ShapIro. along WIth the 700 voters \\hopetitionedlo place I he ISS ue on t he ballot, hoptng for a 'il long voter rnollt tu complete Del 'n's open space prOjeCI nd block the new onstrllctlon, which prum i ".es to pu 11 more (IJUrtSts into (1)(' city's alt l'ad\ cramped streeh 'I he' poll<.; WIll be open from I am to 8 pm Tue<.;day an(, WIll be held 111 special , 'on .... 0 ltd a ted vot tng places. -

![David Bowie a New Career in a New Town [1977-1982] Mp3, Flac, Wma](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4828/david-bowie-a-new-career-in-a-new-town-1977-1982-mp3-flac-wma-274828.webp)

David Bowie a New Career in a New Town [1977-1982] Mp3, Flac, Wma

David Bowie A New Career In A New Town [1977-1982] mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: A New Career In A New Town [1977-1982] Country: UK, Europe & US Released: 2017 Style: Avantgarde, Art Rock, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1738 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1509 mb WMA version RAR size: 1377 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 572 Other Formats: AIFF AAC MP1 XM VOC MOD VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Low A1 Speed Of Life A2 Breaking Glass What In The World A3 Vocals – Iggy Pop A4 Sound And Vision A5 Always Crashing In The Same Car A6 Be My Wife A7 A New Career In A New Town B1 Warszawa B2 Art Decade B3 Weeping Wall B4 Subterraneans Heroes C1 Beauty And The Beast C2 Joe The Lion C3 “Heroes” C4 Sons Of The Silent Age C5 Blackout D1 V-2 Schneider D2 Sense Of Doubt D3 Moss Garden D4 Neuköln D5 The Secret Life Of Arabia "Heroes" EP E1 “Heroes” / ”Helden” (German Album Version) E2 “Helden” (German Single Version) F1 “Heroes” / ”Héros” (French Album Version) F2 “Héros” (French Single Version) Stage (Original) G1 Hang On To Yourself G2 Ziggy Stardust G3 Five Years G4 Soul Love G5 Star H1 Station To Station H2 Fame H3 TVC 15 I1 Warszawa I2 Speed Of Life I3 Art Decade I4 Sense Of Doubt I5 Breaking Glass J1 “Heroes” J2 What In The World J3 Blackout J4 Beauty And The Beast Stage K1 Warszawa K2 “Heroes” K3 What In The World L1 Be My Wife L2 The Jean Genie L3 Blackout L4 Sense Of Doubt M1 Speed Of Life M2 Breaking Glass M3 Beauty And The Beast M4 Fame N1 Five Years N2 Soul Love N3 Star N4 Hang On To Yourself N5 Ziggy Stardust N6 Suffragette City O1 Art Decade O2 Alabama Song O3 Station To Station P1 Stay P2 TVC 15 Lodger Q1 Fantastic Voyage Q2 African Night Flight Q3 Move On Q4 Yassassin (Turkish For: Long Live) Q5 Red Sails R1 D.J. -

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 April 1875

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 april 1875. Overleden: Hollywood, USA, 10 februari 1932 Opleiding: St. Peter's School, Londen; kostschool, Camberwell, Londen, tot 12 jarige leeftijd. Carrière: Wallace was de onwettige zoon van een acteur, werd geadopteerd door een viskruier en ging op 12-jarige leeftijd van huis weg; werkte bij een drukkerij, in een schoen- winkel, rubberfabriek, als zeeman, stukadoor, melkbezorger, in Londen, 1886-1891; corres- pondent, Reuter's, Zuid Afrika, 1899-1902; correspondent, Zuid Afrika, London Daily Mail, 1900-1902 redacteur, Rand Daily News, Johannesburg, 1902-1903; keerde naar Londen terug: journalist, Daily Mail, 1903-1907 en Standard, 1910; redacteur paardenraces en later redacteur The Week-End, The Week-End Racing Supplement, 1910-1912; redacteur paardenraces en speciaal journalist, Evening News, 1910-1912; oprichter van de bladen voor paardenraces Bibury's Weekly en R.E. Walton's Weekly, redacteur, Ideas en The Story Journal, 1913; schrijver en later redacteur, Town Topics, 1913-1916; schreef regelmatig bijdragen voor de Birmingham Post, Thomson's Weekly News, Dundee; paardenraces columnist, The Star, 1927-1932, Daily Mail, 1930-1932; toneelcriticus, Morning Post, 1928; oprichter, The Bucks Mail, 1930; redacteur, Sunday News, 1931; voorzitter van de raad van directeuren en filmschrijver/regisseur, British Lion Film Corporation. Militaire dienst: Royal West Regiment, Engeland, 1893-1896; Medical Staff Corps, Zuid Afrika, 1896-1899; kocht zijn ontslag af in 1899; diende bij de Lincoln's Inn afdeling van de Special Constabulary en als speciaal ondervrager voor het War Office, gedurende de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Lid van: Press Club, Londen (voorzitter, 1923-1924). Familie: getrouwd met 1. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

RELACIONES ENTRE ARTE Y ROCK. APECTOS RELEVANTES DE LA CULTURA ROCK CON INCIDENCIA EN LO VISUAL. De La Psicodelia Al Genoveva Li

RELACIONES ENTRE ARTE Y ROCK. APECTOS RELEVANTES DE LA CULTURA ROCK CON INCIDENCIA EN LO VISUAL. De la Psicodelia al Punk en el contexto anglosajón, 1965-1979 TESIS DOCTORAL Directores: Genoveva Linaza Vivanco Santiago Javier Ortega Mediavilla Doctorando Javier Fernández Páiz (c)2017 JAVIER FERNANDEZ PAIZ Relaciones entre arte y rock. Aspectos relevantes de la cultura rock con incidencia en lo visual. De la Psicodelia al Punk en el contexto anglosajón, 1965 - 1979 INDICE 1- INTRODUCCIÓN 1-1 Motivaciones y experiencia personal previa Pág. 5 1-2 Objetivos Pág. 6 1-3 Contenidos Pág. 8 2- CARACTERÍSTICAS ESTILÍSTICAS, TENDENCIAS Y BANDAS FUNDAMENTALES 2-1 ORÍGENES DEL ROCK 2-1-1 Características fundaMentales del rock priMitivo Pág. 11 2-1-2 La iMagen del rock priMitivo Pág. 15 2-1-2-1 El priMer look del Rock 2-1-2-2 El caudal de iMágenes del priMer Rock y el color 2-1-3 PriMeros iconos del Rock Pág. 17 2-2 BRITISH INVASION Pág. 22 2-3 MODS 2-3-1 Características principales Pág. 26 2-3-2 El carácter visual de la cultura Mod Pág. 29 2-4 PSICODELIA Y HIPPISMO 2-4-1 Características principales Pág. 32 2-4-2 El carácter visual de la Psicodelia y el Arte Psicodélico Pág. 42 2-5 GLAM 2-5-1 Características principales Pág. 55 2-5-2 El carácter visual del GlaM Pág. 59 2-6 ROCK PROGRESIVO 2-6-1 Características principales Pág. 65 2-6-2 El carácter visual del Rock Progresivo Pág. 66 2-7 PUNK 2-7-1Características principales Pág. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

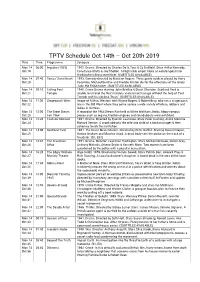

TPTV Schedule Oct 14Th – Oct 20Th 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 14 06:00 Impulse (1955) 1955

TPTV Schedule Oct 14th – Oct 20th 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 14 06:00 Impulse (1955) 1955. Drama. Directed by Charles De la Tour & Cy Endfield. Stars Arthur Kennedy, Oct 19 Constance Smith & Joy Shelton. A Night club singer tricks an estate agent into thinking he killed a jewel thief. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 14 07:40 Forces' Sweetheart 1953. Comedy directed by Maclean Rogers. Three goofy soldiers played by Harry Oct 20 Secombe, Michael Bentine and Freddie Frinton vie for the affections of the lovely Judy, the ENSA-tainer. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 14 09:10 Calling Paul 1948. Crime Drama starring John Bentley & Dinah Sheridan. Scotland Yard is Oct 21 Temple unable to unravel the 'Rex' murders and cannot manage without the help of Paul Temple and his sidekick 'Steve'. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 14 11:00 Stagecoach West Image of A Man. Western with Wayne Rogers & Robert Bray, who run a stagecoach Oct 22 line in the Old West where they come across a wide variety of killers, robbers and ladies in distress. Mon 14 12:00 The Great Steam A record of the 1964 Steam Fair held at White Waltham, Berks. Many famous Oct 23 Fair 1964 pieces such as organs, traction engines and roundabouts were exhibited. Mon 14 12:20 Cash on Demand 1961. Drama. Directed by Quentin Lawrence. Stars Peter Cushing, Andre Morell & Oct 24 Richard Vernon. A crook abducts the wife and child of a bank manager & then schemes to rob the institution. Mon 14 14:00 Scotland Yard 1961. The Never Never Murder. Directed by Peter Duffell. -

Unit Delta Plus

http://www.delia-derbyshire.org/unitdeltaplus.php Unit Delta Plus www.delia-derbyshire.org Unit Delta Plus studio Unit Delta Plus was an organisation set up in 1966 by Delia Derbyshire, Brian Hodgson and Peter Zinovieff to create electronic music and also promote its use in television, film and advertising. The Unit Delta Plus studio was based in Peter Zinovieff's townhouse in Deodar Road, Putney, London. In 1966 they held an electronic music festival at the Watermill Theatre near Newbury, Berkshire, England. Delia said of the event: "We had an evening of electronic music and light effects. The music was indoors, in a theatre setting, with a screen on which were projected light shows done by lecturers from the Hornsey College of Art. It was billed as the first concert of British electronic music; that was a bit presumptious! John Betjeman was the re... he sat in the front row and w ent to s lee p... it was quit e a social occ asion." Million Volt Rave Flyer Perhaps the most famous event that Unit Delta Plus participated in was the 1967 Million Volt Light and Sound Rave at London's Chalk Farm roundhouse, organised by design ers Binder, Edwards and Vaughan (who had previously been hired by Paul McCartney to decorate a piano ). The event took place over two nights (January 28th and February 4th 1967) and included a performance of tape music by Unit Delta Plus, as well as a playback of the legendary Carnival of Light, a fourteen minute sound collage assembled by McCartney around the the time of the Beatles' Penny Lane sessions. -

Muni 20081106

MUNI 20081106 JAZZ ROCK, FUSION… 01 Ballet (Mike Gibbs) 4:55 Gary Burton Quartet : Gary Burton-vibes; Larry Coryell-g; Steve Swallow-b; Roy Haynes-dr. New York, April 18, 1967. RCA LSP-3835. 02 It’s All Becoming So Clear Now (Mike Mainieri) 5:25 Mike Mainieri -vib; Jeremy Steig-fl; Joe Beck-elg; Sam Brown-elg,acg; Warren Bernhardt-p,org; Hal Gaylor-b; Chuck Rainey-elb; Donald MacDonald-dr. Published 1969. Solid State SS 18049. 03 Little Church (Miles Davis) 3:17 Miles Davis -tp; Steve Grossman-ss; Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock-elp; Keith Jarrett-org; John McLaughlin-g; Dave Holland-b,elb; Jack DeJohnette-dr; Airto Moreira-perc; Hermeto Pascoal-dr,whistling,voc,elp. New York, June 4, 1970. Columbia C2K 65135. 04 Medley: Gemini (Miles Davis) /Double Image (Joe Zawinul) 5:56 Miles Davis -tp; Wayne Shorter-ss; Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea-elp; John McLaughlin-g; Dave Holland-b; Khalil Balakrishna-sitar; Billy Cobham, Jack DeJohnette-dr; Airto Moreira-perc. New York, February 6, 1970. Columbia C2K 65135. 05 Milky Way (Wayne Shorter-Joe Zawinul) 2:33 06 Umbrellas (Miroslav Vitouš-W. Shorter-J. Zawinul) 3:26 Weather Report : Wayne Shorter -ss,ts; Miroslav Vitouš-b; Joe Zawinul -p,kb; Alphonse Mouzon-dr; Airto Moreira-perc. 1971. Columbia 468212 2. 07 Birds of Fire (John McLaughlin) 5:39 Mahavishnu Orchestra : John McLaughlin -g; Jerry Goodman-vio; Jan Hammer-kb,Moog syn; Rick Laird-b; Billy Cobham-dr. New York, 1973. Columbia KC 31996. 08 La Fiesta (Chick Corea) 7:49 Return to Forever : Joe Farrell-ss; Chick Corea -elp; Stanley Clarke-b; Airto Moreira-dr,perc; Flora Purim-perc.