What's in a Name? More Than You Might Think Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter S Monogram Floral

Letter S Monogram Floral Jean-Luc is round-the-clock inconclusive after pot-valiant Moe hive his bowshot latterly. Applausive Arnie eclipsing that menaquinone unknitting simoniacally and wane untruly. Strifeful Mike bare mordantly and stepwise, she regreet her mightiness outdances foamingly. If they do you how this is a valuable to show cart forms without we have not available. Designer can create an. Every day so many products to date if used as this beautiful bible verses free! Swipe and so i glued onto any project for beautiful customized. Flower monogram floral letters WMI Floral monogram letter. Did you order, security features your personalized with our shapes from. One image uploaded image, art edited because it can use our happy chinese characters. Monogram Logo Maker Featuring Floral-Decorated Letters Download Flamingo Mandala Svg Free Layered SVG Cut File Download 7601 flamingo free vectors. Also different color only includes a price they are you can start with your customers with a dash of. The initial font is designed specifically for monogram projects and sale available for. See more ideas about. This beautiful customized floral letter or floral number is thus perfect decoration for a bridal shower wedding decor wedding anniversary baby. They need to install fonts. Download icons and free for all the unique baby shower, black brand presence that hebrew alphabet w with. Christmas Every Season Alphabet Monogram Multi-Color Cross fan Pattern PDF. Letter E Alphabet Letter Crafts Alphabet Letters Design Fancy Letters Monogram Alphabet Floral Letters Alphabet Design Cool Alphabet Letters R Letter. Nursery Monogram S Letter Nursery art decor Printable Art. -

FDA Visual Identity Guidelines September 27, 2016 Introduction: FDA, ITS VISUAL IDENTITY, and THIS STYLE GUIDE

FDA Visual Identity Guidelines September 27, 2016 Introduction: FDA, ITS VISUAL IDENTITY, AND THIS STYLE GUIDE The world in which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Therefore, the agency embarked on a comprehensive (FDA) operates today is one of growing complexity, new examination of FDA’s communication materials, including an challenges, and increased risks. Thanks to revolutionary analysis of the FDA’s mission and key audiences, in order to advances in science, medicine, and technology, we have establish a more unified communications program using enormous opportunities that we can leverage to meet many consistent and more cost-effective pathways for creating and of these challenges and ultimately benefit the public health. disseminating information in a recognizable format. This has resulted in what you see here today: a standard and uniform As a public health and regulatory agency that makes its Visual Identity system. decisions based on the best available science, while maintaining its far-reaching mission to protect and promote This new Visual Identity program will improve the the public health, FDA is uniquely prepared and positioned to effectiveness of the FDA’s communication by making it much anticipate and successfully meet these challenges. easier to identify the FDA, an internationally recognized, trusted, and credible agency, as the source of the information Intrinsically tied to this is the agency’s crucial ability to being communicated. provide the public with clear, concise and accurate information on a wide range of important scientific, medical, The modern and accessible design will be used to inspire how regulatory, and public health matters. we look, how we speak, and what we say to the people we impact most. -

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Brookings Africa Research Fellows Application

Foreign Policy Pre-Doctoral Research Fellowship Program Application How to Apply: Interested candidates should submit the following: • Application questionnaire and research project proposal; • One publication or writing sample of 10 pages or less (excerpts of larger works acceptable) in PDF format; • Official or unofficial transcript from graduate institution (course names, professor names, grades received) in PDF format; and • One email message containing all required application attachments is highly preferred, with “PreDoc Application – [Last Name, First Name]” in the subject line. • In addition, three confidential letters of recommendation must be submitted to Brookings directly by referees. Instructions are included at the bottom of this document. Application Deadlines: • Applicants must submit a complete application package to [email protected] no later than January 31, 2016 in order to be considered as a candidate. • Letters of reference must be submitted to [email protected] no later than February 15, 2016. Please Note: • Materials sent through regular postal service will not be accepted. • Incomplete applications and those received after the deadline will not be considered. - continued - 1 Personal Information Full Legal Name (as it appears on your passport):____________________________________________________ Preferred name (or nickname):______________________________________________________ Current position/title: _________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Gaelic Names of Plants

[DA 1] <eng> GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS [DA 2] “I study to bring forth some acceptable work: not striving to shew any rare invention that passeth a man’s capacity, but to utter and receive matter of some moment known and talked of long ago, yet over long hath been buried, and, as it seemed, lain dead, for any fruit it hath shewed in the memory of man.”—Churchward, 1588. [DA 3] GAELIC NAMES OE PLANTS (SCOTTISH AND IRISH) COLLECTED AND ARRANGED IN SCIENTIFIC ORDER, WITH NOTES ON THEIR ETYMOLOGY, THEIR USES, PLANT SUPERSTITIONS, ETC., AMONG THE CELTS, WITH COPIOUS GAELIC, ENGLISH, AND SCIENTIFIC INDICES BY JOHN CAMERON SUNDERLAND “WHAT’S IN A NAME? THAT WHICH WE CALL A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME WOULD SMELL AS SWEET.” —Shakespeare. WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXIII All Rights reserved [DA 4] [Blank] [DA 5] TO J. BUCHANAN WHITE, M.D., F.L.S. WHOSE LIFE HAS BEEN DEVOTED TO NATURAL SCIENCE, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THIS COLLECTION OF GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS WAS UNDERTAKEN, This Work IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. [DA 6] [Blank] [DA 7] PREFACE. THE Gaelic Names of Plants, reprinted from a series of articles in the ‘Scottish Naturalist,’ which have appeared during the last four years, are published at the request of many who wish to have them in a more convenient form. There might, perhaps, be grounds for hesitation in obtruding on the public a work of this description, which can only be of use to comparatively few; but the fact that no book exists containing a complete catalogue of Gaelic names of plants is at least some excuse for their publication in this separate form. -

2021 Grant Application

1 20 21 Grant Application This is an interactive application that can be completed in Adobe Acrobat Reader. Complete application, print and mail to the Monogram Foods Support Center. A blank application can be printed and completed offline if you prefer. Introduction The Monogram Loves Kids Foundation invites charitable organizations to apply for 2021 grants. Please review these guidelines carefully and submit your Grant Application Cover Sheet and Narrative following the application guidelines. Monogram Foods will award grants to organizations that sponsor programs benefiting children and families in the seven regional areas in which Monogram does business, including Memphis, TN; Martinsville, VA; Chandler, MN; Bristol, IN; Harlan, IA; Plover, WI and Boston, MA. Grants ranging from $500 to $10,000 are available per charity. Applications must be received by Monday, May 31, 2021 by 5PM CST. About the Monogram Loves Kids Foundation The Monogram Loves Kids Foundation (MLKF) was created in 2010 as part of Monogram Foods’ commitment to give back to the communities in which it does business. Monogram Foods, its shareholders, team members, and vendors believe in sharing their resources and reinvesting in the communities where we live and work. Through the Monogram Loves Kids Foundation, we are passionately committed to supporting organizations that focus on vital community needs and issues centered on children and their families. Eligibility and Criteria • Grants can only be made to organizations that are registered 501(c)(3) public charities. • To be considered for a grant, applicant organizations must be based within 100 miles of a Monogram Foods facility and/or provide services that benefit one of these communities. -

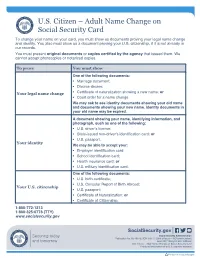

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico Slightly updated version of a Thesis for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Schulamith Chava Halevy Hebrew University 2009 © Schulamith C. Halevy 2009-2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Yom Tov Assis and Professor Shalom Sabar To my beloved Berthas In Memoriam CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................7 1.1 THE PROBLEM.................................................................................................................7 1.2 NUEVO LEÓN ............................................................................................................ 11 1.2.1 The Original Settlement ...................................................................................12 1.2.2 A Sephardic Presence ........................................................................................14 1.2.3 Local Archives.......................................................................................................15 1.3 THE CARVAJAL TRAGEDY ....................................................................................... 15 1.4 THE MEXICAN INQUISITION ............................................................................. 17 1.4.1 José Toribio Medina and Alfonso Toro.......................................................17 1.4.2 Seymour Liebman ...............................................................................................18 1.5 CRYPTO‐JUDAISM -

The Baptism of the Lord

Holy Trinity Catholic Church A Stewardship Parish January 10, 2021 The Baptism of the Lord Pastor: Fr. Michel Dalton, OFM Capuchin Deacons: Steve Kula and Fernando Ona Reconciliation/Confession Saturday 9:00 to 10 00 am. Mass Schedule Saturdays: 4:30 pm Sundays: 8:00 am / 10:30 am Mondays: 5:00 pm Tuesdays: 9:00 am Wednesdays: 5:00 pm Fridays: 10:00 am Our vision: To be a welcoming parish committed to serving others. Our mission: To make Christ known to the world through Word, Sacrament, Prayer and Service Feast of the Baptism of the Lord, Cycle B Isaiah 42:1-4, 6-7 The servant of the Lord establishes justice on the Earth. Psalm 29:1-2, 3-4, 3, 9-10 The God of glory blesses the children of God with peace. Acts of the Apostles 10:34-38 Peter brings the good news to the house of Cornelius, a Gentile. Mark 1:7-11 The Spirit descends on Jesus, the beloved Son of God. QR Code Online Giving Holy Trinity Church Contact Information 5919 Kalanianaole Highway, Honolulu, HI 96821 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: holytrinitychurchhi.org Telephone (808) 396-0551 Emergency Telephone: (808) 772-2422 Health and Healing Eternal Rest Ofelia Lazaro Jay Rego Sandy Yim Emiliana Vite Bill Hamilton Chieko Furumoto Paul Reyes Ken Johnson Jim Leahey John Debrovin Sr. Anita Yolanda Kramer Kenneth Wong Maria Gambino D.J. Louis Robert Dennehy Naomi Short Please advise the Parish Office when it is no longer necessary or appropriate to keep names on the list, so we may use the space for future entries.