Fraud and Forgery of the Testator's Will Or Signature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Trafficking and Exploitation

HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND EXPLOITATION MANUAL FOR TEACHERS Third Edition Recommended by the order of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Armenia as a supplemental material for teachers of secondary educational institutions Authors: Silva Petrosyan, Heghine Khachatryan, Ruzanna Muradyan, Serob Khachatryan, Koryun Nahapetyan Updated by Nune Asatryan The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This publication has been issued without formal language editing by IOM. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Mission in Armenia 14, Petros Adamyan Str. UN House, Yerevan 0010, Armenia Telephone: ¥+374 10¤ 58 56 92, 58 37 86 Facsimile: ¥+374 10¤ 54 33 65 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.iom.int/countries/armenia © 2016 International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: the Dawn of the Electronic Will

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 42 2008 Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: The Dawn of the Electronic Will Joseph Karl Grant Capital University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph K. Grant, Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: The Dawn of the Electronic Will, 42 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 105 (2008). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol42/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHATTERING AND MOVING BEYOND THE GUTENBERG PARADIGM: THE DAWN OF THE ELECTRONIC WILL Joseph Karl Grant* INTRODUCTION Picture yourself watching a movie. In the film, a group of four siblings are dressed in dark suits and dresses. The siblings, Bill Jones, Robert Jones, Margaret Jones and Sally Johnson, have just returned from their elderly mother's funeral. They sit quietly in their mother's attorney's office intently watching and listening to a videotape their mother, Ms. Vivian Jones, made before her death. On the videotape, Ms. Jones expresses her last will and testament. Ms. Jones clearly states that she would like her sizable real estate holdings to be divided equally among her four children and her valuable blue-chip stock investments to be used to pay for her grandchildren's education. -

Case and ~C®Mment

251 CASE AND ~C®MMENT. CROWN -SERVANT- INCORPORATION -IMMUNITY FROM BEING SUED. The recent case of Gilleghan v. Minister of Healthl decided by Farwell, J., is a decision on the questions : Will an action lie against a Minister-of the Crown in respect of an act admittedly done as a Minister of the Crown? Or -is the true view that the only remedy is against the Crown by petition of right? Does the mere incorporation. of a servant of the Crown confer the privilege of suing and the liability to be sued? The rationale for the general rule that a servant of the Crown cannot be sued in his official capacity is that the servant holds no assets in his official capacity which can be seized in satisfaction of a judgment. He holds only on behalf of the Crown.2 Collins, M.R., in Bainbridge v. Postmaster-General3 said : "The revenue of the country cannot be reached by an action against an official, unless there is some provision to be found in the legisla~ tion to enable this to be done." In the Gilleghan case the defendant moved to-strike out the statement of claim. The Minister of Health was established by the Ministry of Health Act- which provided, inter alia, that the Minister "may sue and be sued in the name of the Minister of Health" and that "for the purpose of acquiring and holding land" the Minister for the time being "shall be a corporation sole." Farwell, J ., decided that the provision that the Minister may sue and be sued does not give the plaintiff a cause of action for breach of contract against the Minister. -

The Decline of Revocation by Physical Act

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2019 The Decline of Revocation by Physical Act Barry Cushman Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Insurance Law Commons Recommended Citation Barry Cushman, The Decline of Revocation by Physical Act, 54 Real Prop., Tr. & Est. L.J. 243 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/1416 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DECLINE OF REVOCATION BY PHYSICAL ACT Barry Cushman* Author's Synopsis: The power to revoke one's will by physical act was enshrined in Anglo-American law in 1677 by the Statute of Frauds. It remains the law in Great Britain, in such developed Commonwealth countries as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and in each state of the United States ofAmerica. Yet the revocation of wills by physical act has become badly out of phase with the law governing nonprobate transfers, which as a general matter requires that an instrument of transfer be revoked only by a writing signed by the transferor. This Article surveys the place of revocation by physical act in the law governing will substitutes, such as payable-on-death designations on bank accounts, transfer-on-deathdesignations on brokerage accounts, life insurance and annuities, beneficiary deeds, and revocable trusts. -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 .............................................................................................. -

The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation

LENS FINAL 12/1/2010 5:47:02 PM Honest Confusion: The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation Jill Wieber Lens∗ I. INTRODUCTION Suppose that a plaintiff is injured in a rear-end collision car accident. Even though the rear-end collision was not a dramatic accident, the plaintiff incurred extensive medical expenses because of a preexisting medical condition. Through a negligence claim, the plaintiff can recover compensatory damages based on his medical expenses. But is it fair that the defendant should be liable for all of the damages? It is not as if he rear-ended the plaintiff on purpose. Maybe the fact that defendant’s conduct was not reprehensible should reduce the amount of damages that the plaintiff recovers. Any first-year torts student knows that the defendant’s argument will not succeed. The defendant’s conduct does not control the amount of the plaintiff’s compensatory damages. The damages are based on the plaintiff’s injury because, in tort law, the purpose of compensatory damages is to make the plaintiff whole by putting him in the same position as if the tort had not occurred.1 But there are tort claims where the amount of compensatory damages is not always based on the plaintiff’s injury. Suppose that a defendant fraudulently misrepresents that a car for sale is brand-new. The plaintiff then offers to purchase the car for $10,000. Had the car actually been new, it would have been worth $15,000, but the car was instead worth only $10,000. As they have for a very long time, the majority of jurisdictions would award the plaintiff $5000 in compensatory damages 2 based on the plaintiff’s expected benefit of the bargain. -

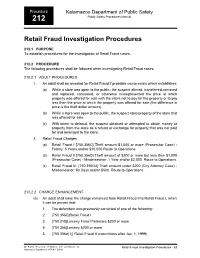

Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures

Procedure Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety Public Safety Procedures Manual 212 Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures 212.1 PURPOSE To establish procedures for the investigation of Retail Fraud cases. 212.2 PROCEDURE The following procedures shall be followed when investigating Retail Fraud cases. 212.2.1 ADULT PROCEDURES 1. An adult shall be arrested for Retail Fraud if probable cause exists which establishes: (a) While a store was open to the public, the suspect altered, transferred, removed and replaced, concealed, or otherwise misrepresented the price at which property was offered for sale with the intent not to pay for the property or to pay less than the price at which the property was offered for sale (the difference in price is the theft dollar amount). (b) While a store was open to the public, the suspect stole property of the store that was offered for sale. (c) With intent to defraud, the suspect obtained or attempted to obtain money or property from the store as a refund or exchange for property that was not paid for and belonged to the store. 2. Retail Fraud Charges (a) Retail Fraud I [750.356C] Theft amount $1,000 or more (Prosecutor Case) - Felony: 5 Years and/or $10,000 Route to Operations. (b) Retail Fraud II [750.356D] Theft amount of $200 or more but less than $1,000 (Prosecutor Case) - Misdemeanor: 1 Year and/or $2,000. Route to Operations. (c) Retail Fraud III- [750.356D4] Theft amount under $200 (City Attorney Case) - Misdemeanor: 93 Days and/or $500. Route to Operations 212.2.2 CHARGE ENHANCEMENT (a) An adult shall have the charge enhanced from Retail Fraud II to Retail Fraud I, when it can be proven that: 1. -

Fraud: District of Columbia by Robert Van Kirk, Williams & Connolly LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Fraud: District of Columbia by Robert Van Kirk, Williams & Connolly LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 16 Mar 2021 | Jurisdiction: District of Columbia, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-029-0846 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to fraud claims under District of Columbia law. This Q&A addresses the elements of actual fraud, including material misrepresentation and reliance, and other types of fraud claims, such as fraudulent concealment and constructive fraud. Elements Generally – nondisclosure of a material fact when there is a duty to disclose (Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (D.C.) v. Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (Md.), 1. What are the elements of a fraud claim in 223 F. Supp. 3d 1, 10 (D.D.C. 2016) (applying District your jurisdiction? of Columbia law)). To state a claim of common law fraud (or fraud in the (Sundberg v. TTR Realty, LLC, 109 A.3d 1123, 1131 inducement) under District of Columbia law, a plaintiff (D.C. 2015).) must plead that: • A material misrepresentation actionable in fraud • The defendant made: must be consciously false and intended to mislead another (Sarete, Inc. v. 1344 U St. Ltd. P’ship, 871 A.2d – a false statement of material fact (see Material 480, 493 (D.C. 2005)). A literally true statement Misrepresentation); that creates a false impression can be actionable in fraud (Jacobson v. Hofgard, 168 F. Supp. 3d 187, 196 – with knowledge of its falsity; and (D.D.C. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES GREG ANDERSON Petitioner, VS. GARY HERBERT et. al. Respondents. PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT Greg Anderson pro se 24 South 7' Street Tooele, Utah 84074 Phone: 385 231-5005 NOV 1 - 2018 QUESTION PRESENTED Is a judgment void on its face, when a State Court steals a paid-for home at the motion to dismiss stage of the proceedings, under the guise that the owner was a tenant, where plaintiff attorneys misrepresented the law and contractual terms of the purchase contract 30 times in a 6 page document, then wrote the "Statement of Facts and Conclusions of Law," with no reference to the purported record, and the judge rubber-stamped plaintiffs claims, and the court denied itself jurisdiction by not strictly adhering to the statute, thereby implicating conspiracy. 11 PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS BELOW Petitioner is Greg Anderson. Respondents Are Gary Herbert in His Official Capacity as Governor of the State of Utah, Sean Reyes in His Official Capacity as Attorney General for the State of Utah, Clark A McClellan, in His Individual Capacity, and in His Official Capacity for His Extra- judicial Acts, Third District Court, in its Official Capacity, Eighth District Court in its Official Capacity, Utah Court of Appeals in its Official Capacity, Daniel W. Kitchen, James L. Ahistrom, Terry Welch, Lynn Kitchen, Gary Kitchen, Mathew J. Kitchen, Mark R. Kitchen, Sandbay LLC Sunlake LLC, Orchid Beach LLC Roosevelt Hills LLC, John or Jane Doe(s) 1 Through 10 Note: No John or Jane Doe's have been named, nor have any other parties. -

Defamation, a Camouflage of Psychic Interests: the Beginning of a Behavioral Analysis

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 15 Issue 4 Issue 4 - October 1962 Article 6 10-1962 Defamation, A Camouflage of Psychic Interests: The Beginning of a Behavioral Analysis Walter Probert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Walter Probert, Defamation, A Camouflage of Psychic Interests: The Beginning of a Behavioral Analysis, 15 Vanderbilt Law Review 1173 (1962) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol15/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Defamation, A Camouflage of Psychic Interests: The Beginning of a Behavioral Analysis Walter Probert* Does the law of defamation need to be reformed? The author thinks so. Professor Probert rejects the doctrine of libel per se and questions the courts' understanding and use of the term "reputation." It is his belief that plaintiffs on an individual bhsis should have increased benefit of the knowledge accumulated by the various social sciences in proving the harm done by the alleged defamation, with more liberalizationin the requirements of pleading and proof than is now generally countenanced by the courts. I. INTRODUCIION What are you going to do with the common law? One time you can bless it for its "skepticism" of the theories of the "fuzzy-heads." Another time you can damn it for its old maid and bigoted isolation from the world of realities. -

The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability

Michigan Law Review Volume 64 Issue 7 1966 Products Liability--The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability John A. Sebert Jr. University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John A. Sebert Jr., Products Liability--The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability, 64 MICH. L. REV. 1350 (1966). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol64/iss7/10 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS Products Liability-The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability The advances in recent years in the field of products liability have probably outshone, in both number a~d significance, the prog ress during the same period in most other areas of the law. These rapid developments in the law of consumer protection have been marked by a consistent tendency to expand the liability· of manu facturers, retailers, and other members of the distributive chain for physical and economic harm caused by defective merchandise made available to the public. Some of the most notable progress has been made in the law of tort liability. A number of courts have adopted the principle that a manufacturer, retailer, or other seller1 of goods is answerable in tort to any user of his product who suffers injuries attributable to a defect in the merchandise, despite the seller's exer cise of reasonable care in dealing with the product and irrespective of the fact that no contractual relationship has ever existed between the seller and the victim.2 This doctrine of strict tort liability, orig inally enunciated by the California Supreme Court in Greenman v. -

Fraud Litigation in Pennsylvania

FRAUD LITIGATION IN PENNSYLVANIA Doc. #531047v.1 - 11/21/2001 1:08 am FRAUD LITIGATION IN PENNSYLVANIA By: Louis C. Long Robert W. Cameron Meyer, Darragh, Buckler, Bebenek & Eck 2000 Frick Building Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania William B. Mallin Patrick R. Kingsley Eckert Seamans Cherin & Mellott 600 Grand Street, 42nd Floor Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 10K11018 Doc. #531047v.1 - 11/21/2001 1:08 am FRAUD LITIGATION IN PENNSYLVANIA Copyright 1993 National Business Institute, Inc. P.O. Box 3067 Eau Claire, WI 54702 All rights reserved. These materials may not be reproduced without permission of National Business Institute, Inc. Additional copies may be ordered by writing National Business Institute, Inc. at the above address. This publication is designed to provide general information prepared by professionals in regards to subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. Although prepared by professionals, this publication should not be utilized as a substitute for professional service in specific situations. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a professional should be sought. Doc. #531047v.1 - 11/21/2001 1:08 am FRAUD LITIGATION IN PENNSYLVANIA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INITIAL CONSIDERATIONS ....................................................................................... 1 II. PLEADINGS AND MOTION PRACTICE.................................................................... 3 A. SPECIFICITY REQUIREMENTS....................................................................................