Fraud Litigation in Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Trafficking and Exploitation

HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND EXPLOITATION MANUAL FOR TEACHERS Third Edition Recommended by the order of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Armenia as a supplemental material for teachers of secondary educational institutions Authors: Silva Petrosyan, Heghine Khachatryan, Ruzanna Muradyan, Serob Khachatryan, Koryun Nahapetyan Updated by Nune Asatryan The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This publication has been issued without formal language editing by IOM. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Mission in Armenia 14, Petros Adamyan Str. UN House, Yerevan 0010, Armenia Telephone: ¥+374 10¤ 58 56 92, 58 37 86 Facsimile: ¥+374 10¤ 54 33 65 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.iom.int/countries/armenia © 2016 International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense

63 Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense Article 15: Criminal Offense A criminal offense is an unlawful act: (a) that is prescribed as a criminal offense by law; (b) whose characteristics are specified by law; and (c) for which a penalty is prescribed by law. Commentary This provision reiterates some of the aspects of the principle of legality and others relating to the purposes and limits of criminal legislation. Reference should be made to Article 2 (“Purpose and Limits of Criminal Legislation”) and Article 3 (“Principle of Legality”) and their accompanying commentaries. Article 16: Criminal Responsibility A person who commits a criminal offense is criminally responsible if: (a) he or she commits a criminal offense, as defined under Article 15, with intention, recklessness, or negligence as defined in Article 18; IOP573A_ModelCodes_Part1.indd 63 6/25/07 10:13:18 AM 64 • General Part, Section (b) no lawful justification exists under Articles 20–22 of the MCC for the commission of the criminal offense; (c) there are no grounds excluding criminal responsibility for the commission of the criminal offense under Articles 2–26 of the MCC; and (d) there are no other statutorily defined grounds excluding criminal responsibility. Commentary When a person is found criminally responsible for the commission of a criminal offense, he or she can be convicted of this offense, and a penalty or penalties may be imposed upon him or her as provided for in the MCC. Article 16 lays down the elements required for a finding of criminal responsibility against a person. -

Corporate Governance

CCCorporateCorporate Governance Carsten Burhop Universität zu KKölnölnölnöln Marc Deloof University of Antwerp 1. General introduction Since the late 1990s, a series of papers published in leading economics and finance journals contain evidence for a significant impact of institutions on financial and economic development (e.g., Acemoglu et al., 2001, 2005; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny – LLSV henceforth – 1997, 1998, 2000; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer – LLS henceforth – 1999, 2008). According to this literature, high-quality institutions cause financial development. In turn, financial development is a driving force behind economic growth. The historical legacy seems to play an important role in the relationship between the financial development of countries, their current institutions and their past institutions. Indeed, prominent contributions demonstrate a strong positive correlation between legal origins (common law is considered to be better than civil law) and three further elements: first, current indices of the rule of law (Acemoglu et al., 2001; Beck et al., 2003); second, financial development (LLSV 1997, 1998; Beck et al, 2003); and third, the dispersion of share ownership and the separation of ownership and control (LLS 1999). In general, shareholders are supposed to have the strongest protection in common-law countries, followed by German-style civil- law countries. Shareholder protection is the weakest in French style civil law countries. In contrast, secured creditors are supposed to be best protected in the German legal system. Consequently, common-law countries have relatively high numbers of listed firms and of initial public offerings and a relatively high ratio of stock market capitalisation to GDP. -

CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS at COMMON LAW Edwin R

[Vol. 102 CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS AT COMMON LAW Edwin R. Keedy t GENERAL PRINCIPLES Much has been written on the law of attempts to commit crimes 1 and much more will be written for this is one of the most interesting and difficult problems of the criminal law.2 In many discussions of criminal attempts decisions dealing with common law attempts, stat- utory attempts and aggravated assaults, such as assaults with intent to murder or to rob, are grouped indiscriminately. Since the defini- tions of statutory attempts frequently differ from the common law concepts,8 and since the meanings of assault differ widely,4 it is be- "Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Pennsylvania. 1. See Beale, Criminal Attempts, 16 HARv. L. REv. 491 (1903); Hoyles, The Essentials of Crime, 46 CAN. L.J. 393, 404 (1910) ; Cook, Act, Intention and Motive in the Criminal Law, 26 YALE L.J. 645 (1917) ; Sayre, Criminal Attempts, 41 HARv. L. REv. 821 (1928) ; Tulin, The Role of Penalties in the Criminal Law, 37 YALE L.J. 1048 (1928) ; Arnold, Criminal Attempts-The Rise and Fall of an Abstraction, 40 YALE L.J. 53 (1930); Curran, Criminal and Non-Criminal Attempts, 19 GEo. L.J. 185, 316 (1931); Strahorn, The Effect of Impossibility on Criminal Attempts, 78 U. OF PA. L. Rtv. 962 (1930); Derby, Criminal Attempt-A Discussion of Some New York Cases, 9 N.Y.U.L.Q. REv. 464 (1932); Turner, Attempts to Commit Crimes, 5 CA=. L.J. 230 (1934) ; Skilton, The Mental Element in a Criminal Attempt, 3 U. -

What Does Intent Mean?

WHAT DOES INTENT MEAN? David Crump* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................. 1060 II. PROTOTYPICAL EXAMPLES OF INTENT DEFINITIONS......... 1062 A. Intent as “Purpose” ..................................................... 1062 B. Intent as Knowledge, Awareness, or the Like ............ 1063 C. Imprecise Definitions, Including Those Not Requiring Either Purpose or Knowledge .................. 1066 D. Specific Intent: What Does It Mean?.......................... 1068 III. THE AMBIGUITY OF THE INTENT DEFINITIONS.................. 1071 A. Proof of Intent and Its Implications for Defining Intent: Circumstantial Evidence and the Jury ........... 1071 B. The Situations in Which Intent Is Placed in Controversy, and the Range of Rebuttals that May Oppose It................................................................... 1074 IV. WHICH DEFINITIONS OF INTENT SHOULD BE USED FOR WHAT KINDS OF MISCONDUCT?....................................... 1078 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................... 1081 * A.B. Harvard College; J.D. University of Texas School of Law. John B. Neibel Professor of Law, University of Houston Law Center. 1059 1060 HOFSTRA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1059 I. INTRODUCTION Imagine a case featuring a manufacturing shop boss who sent his employees into a toxic work environment. As happens at many job sites, hazardous chemicals unavoidably were nearby, and safety always was a matter of reducing their concentration. This attempted solution, however, may mean that dangerous levels of chemicals remain. But this time, the level of toxicity was far higher than usual. There is strong evidence that the shop boss knew about the danger, at least well enough to have realized that it probably had reached a deadly level, but the shop boss disputes this evidence. The employees all became ill, and one of them has died. The survivors sue in an attempt to recover damages for wrongful death. -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 .............................................................................................. -

The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation

LENS FINAL 12/1/2010 5:47:02 PM Honest Confusion: The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation Jill Wieber Lens∗ I. INTRODUCTION Suppose that a plaintiff is injured in a rear-end collision car accident. Even though the rear-end collision was not a dramatic accident, the plaintiff incurred extensive medical expenses because of a preexisting medical condition. Through a negligence claim, the plaintiff can recover compensatory damages based on his medical expenses. But is it fair that the defendant should be liable for all of the damages? It is not as if he rear-ended the plaintiff on purpose. Maybe the fact that defendant’s conduct was not reprehensible should reduce the amount of damages that the plaintiff recovers. Any first-year torts student knows that the defendant’s argument will not succeed. The defendant’s conduct does not control the amount of the plaintiff’s compensatory damages. The damages are based on the plaintiff’s injury because, in tort law, the purpose of compensatory damages is to make the plaintiff whole by putting him in the same position as if the tort had not occurred.1 But there are tort claims where the amount of compensatory damages is not always based on the plaintiff’s injury. Suppose that a defendant fraudulently misrepresents that a car for sale is brand-new. The plaintiff then offers to purchase the car for $10,000. Had the car actually been new, it would have been worth $15,000, but the car was instead worth only $10,000. As they have for a very long time, the majority of jurisdictions would award the plaintiff $5000 in compensatory damages 2 based on the plaintiff’s expected benefit of the bargain. -

The Law, Corporate Finance, and Management

The Law, Corporate Finance, and Management v. 1.0 This is the book The Law, Corporate Finance, and Management (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This book was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. ii Table of Contents About the Authors................................................................................................................. 1 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................. 5 -

What Is Corporate Law?

ISSN 1936-5349 (print) ISSN 1936-5357 (online) HARVARD JOHN M. OLIN CENTER FOR LAW, ECONOMICS, AND BUSINESS THE ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF CORPORATE LAW: WHAT IS CORPORATE LAW? John Armour, Henry Hansmann, Reinier Kraakman Discussion Paper No. 643 7/2009 Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper Series: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/ The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=####### This paper is also a discussion paper of the John M. Olin Center’s Program on Corporate Governance. The Essential Elements of Corporate Law What is Corporate Law? John Armour University of Oxford - Faculty of Law; Oxford-Man Institute of Quantitative Finance; European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) Henry Hansmann Yale Law School; European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) Reinier Kraakman Harvard Law School; John M. Olin Center for Law; European Corporate Governance Institute Abstract: This article is the first chapter of the second edition of The Anatomy of Corporate Law: A Comparative and Functional Approach, by Reinier Kraakman, John Armour, Paul Davies, Luca Enriques, Henry Hansmann, Gerard Hertig, Klaus Hopt, Hideki Kanda and Edward Rock (Oxford University Press, 2009). The book as a whole provides a functional analysis of corporate (or company) law in Europe, the U.S., and Japan. Its organization reflects the structure of corporate law across all jurisdictions, while individual chapters explore the diversity of jurisdictional approaches to the common problems of corporate law. In its second edition, the book has been significantly revised and expanded. -

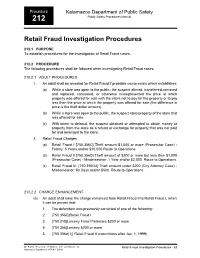

Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures

Procedure Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety Public Safety Procedures Manual 212 Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures 212.1 PURPOSE To establish procedures for the investigation of Retail Fraud cases. 212.2 PROCEDURE The following procedures shall be followed when investigating Retail Fraud cases. 212.2.1 ADULT PROCEDURES 1. An adult shall be arrested for Retail Fraud if probable cause exists which establishes: (a) While a store was open to the public, the suspect altered, transferred, removed and replaced, concealed, or otherwise misrepresented the price at which property was offered for sale with the intent not to pay for the property or to pay less than the price at which the property was offered for sale (the difference in price is the theft dollar amount). (b) While a store was open to the public, the suspect stole property of the store that was offered for sale. (c) With intent to defraud, the suspect obtained or attempted to obtain money or property from the store as a refund or exchange for property that was not paid for and belonged to the store. 2. Retail Fraud Charges (a) Retail Fraud I [750.356C] Theft amount $1,000 or more (Prosecutor Case) - Felony: 5 Years and/or $10,000 Route to Operations. (b) Retail Fraud II [750.356D] Theft amount of $200 or more but less than $1,000 (Prosecutor Case) - Misdemeanor: 1 Year and/or $2,000. Route to Operations. (c) Retail Fraud III- [750.356D4] Theft amount under $200 (City Attorney Case) - Misdemeanor: 93 Days and/or $500. Route to Operations 212.2.2 CHARGE ENHANCEMENT (a) An adult shall have the charge enhanced from Retail Fraud II to Retail Fraud I, when it can be proven that: 1. -

Fraud: District of Columbia by Robert Van Kirk, Williams & Connolly LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Fraud: District of Columbia by Robert Van Kirk, Williams & Connolly LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 16 Mar 2021 | Jurisdiction: District of Columbia, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-029-0846 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to fraud claims under District of Columbia law. This Q&A addresses the elements of actual fraud, including material misrepresentation and reliance, and other types of fraud claims, such as fraudulent concealment and constructive fraud. Elements Generally – nondisclosure of a material fact when there is a duty to disclose (Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (D.C.) v. Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (Md.), 1. What are the elements of a fraud claim in 223 F. Supp. 3d 1, 10 (D.D.C. 2016) (applying District your jurisdiction? of Columbia law)). To state a claim of common law fraud (or fraud in the (Sundberg v. TTR Realty, LLC, 109 A.3d 1123, 1131 inducement) under District of Columbia law, a plaintiff (D.C. 2015).) must plead that: • A material misrepresentation actionable in fraud • The defendant made: must be consciously false and intended to mislead another (Sarete, Inc. v. 1344 U St. Ltd. P’ship, 871 A.2d – a false statement of material fact (see Material 480, 493 (D.C. 2005)). A literally true statement Misrepresentation); that creates a false impression can be actionable in fraud (Jacobson v. Hofgard, 168 F. Supp. 3d 187, 196 – with knowledge of its falsity; and (D.D.C. -

THE CASE of "INTENT": SHOULD the ELEMENTS of MURDER BE EXPANDED in VIRGINIA? David L

THE CASE OF "INTENT": SHOULD THE ELEMENTS OF MURDER BE EXPANDED IN VIRGINIA? David L. Thomas INTRODUCTION The word "murderer" connotes in human beings an intensity of feeling that ranks near the top of the human emotional spectrum. Although the "murderer" is to be abhorred, his status is to be protected. That is, the term "murderer" embraces such magnitude of horror that the label must be saved only for those who truly deserve it. Therefore, the state legislature has established strict rules concerning the designation "first degree murderer." Among the rules is one that demands that the slayer possess not only the express "intent to kill," but also a "willful, premeditated, and deliberate" mindset. My inquiry here examines whether that rule of first degree murder in Virginia can be replaced with either an "intention to cause serious bodily injury" or a "reckless disregard for human life." DISCUSSION HISTORY As common law murder evolved, a debate raged, and remains, as to what constitutes first degree and second degree murder.' Each state has instituted its own , See generally R. PERKINS, PERKINS ON CRIMINAL LAW 86-96 (1969). Perkins discusses the origins of the degrees of murder, which were embodied in a 1794 Pennsylvania statute that came to be known as the "Pennsylvania Pattern." Today this doctrine is no longer embodied in an existing authoritative statute but survives in modern case law in Commonwealth v. Drum, 58 Pa. 9 (1868). ATTEMPTED SECOND DEGREE MURDER--Does It Exist? Generally when one speaks of attempted murder, the list of essential elements includes only those used in first degree murder offenses.