The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Trafficking and Exploitation

HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND EXPLOITATION MANUAL FOR TEACHERS Third Edition Recommended by the order of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Armenia as a supplemental material for teachers of secondary educational institutions Authors: Silva Petrosyan, Heghine Khachatryan, Ruzanna Muradyan, Serob Khachatryan, Koryun Nahapetyan Updated by Nune Asatryan The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This publication has been issued without formal language editing by IOM. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Mission in Armenia 14, Petros Adamyan Str. UN House, Yerevan 0010, Armenia Telephone: ¥+374 10¤ 58 56 92, 58 37 86 Facsimile: ¥+374 10¤ 54 33 65 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.iom.int/countries/armenia © 2016 International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Expectation, Reliance, and the Two Contractual Wrongs

Expectation, Reliance, and the Two Contractual Wrongs CHRISTOPHER T. WONNELL* TABLE OF CONTENTS L INTRODUCTION: THE PLACE OF EXPECTATION AND RELIANCE IN CONTRACTUAL DECISION MAKING ............................................. 54 A. Two ContractualDecisions in Need of Moral Assessment ................54 B. Six Motivesfor Making and Then Breaking a Particular Contract................................................................................................. 60 1. Taking Advantage of NonsimultaneousPerformances ................... 60 2. Making a Threat to Breach in the Face of Situational Monopoly Credible....................................................................... 62 3. Refusing to Carry Through on an Agreed-upon Allocation of Risk ......................................................................... 63 4. Seeking to AppropriateInformation Productively Brought to Bearon the Transactionby the Promisee..................... 66 5. Seeking to Avoid the Contract Because of a Mistake That Makes the ContractMore Burdensome to the PromisorThan Anticipated and Correspondingly More Profitableto the Promisee.................................................. 72 6. Seeking to Avoid the Contract Because of a Mistake That Makes the ContractMore Burdensome to the PromisorThan Anticipated Without Becoming CorrespondinglyMore Profitableto the Promisee........................ 75 * Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. J.D. 1982, University of Michigan; B.A. 1979, Northwestern University. This Article was selected by -

1. the Issue Is Whether the Trial Court Erred in Awarding the Rancher, An

STUDENT ANSWER 1: 1. The issue is whether the trial court erred in awarding the Rancher, an aggrieved party in a breach of contract claim, a $500,000 award for restoration of the Ranch when the breaching party showed by expert testimony a diminution of value of only $20,000 in the Ranch’s current condition? The trial court had already determined that an enforceable contract existed between the Rancher and Gasco, and that the contract was breached by Gasco when it failed to restore the Ranch to its pre-exploration condition by March 31. The sole issue here is the issue of damages. Specifically, whether the award of $500,000 to restore the ranch was grossly and unfairly out of proportion to the benefit to be achieved? Remedies for breach of contract seek to compensate an aggrieved party for profits that were prevented and losses sustained due to the breach of contract. Typically, three (3) types of damages are available to an aggrieved party under Common Law contract law (UCC Article 2 does not apply here since the contract does not involve the sale of good but rather a lease for real property): (1) restitution damages, (2) reliance damages, and (3) expectation damages. The first two types of damages help an aggrieved party recover the benefit bestowed upon a breaching party to prevent its unjust enrichment, which includes the recovery of out-of-pocket expenses, if foreseeable and ascertainable at the time of the breach, that were wasted by the aggrieved party in getting ready to perform. The third type of damages, expectation damages, aims to place an aggrieved party in the same financial position as if the contract had been fully performed and not breached. -

North Dakota Century Code T14c02

CHAPTER 14-02 PERSONAL RIGHTS 14-02-01. General personal rights. Every person, subject to the qualifications and restrictions provided by law, has the right of protection from bodily restraint or harm, from personal insult, from defamation, and from injury to the person's personal relations. 14-02-02. Defamation classified. Defamation is effected by: 1. Libel; or 2. Slander. 14-02-03. Civil libel defined. Libel is a false and unprivileged publication by writing, printing, picture, effigy, or other fixed representation to the eye, which exposes any person to hatred, contempt, ridicule, or obloquy, or which causes the person to be shunned or avoided, or which has a tendency to injure the person in the person's occupation. 14-02-04. Civil slander defined. Slander is a false and unprivileged publication other than libel, which: 1. Charges any person with crime, or with having been indicted, convicted, or punished for crime; 2. Imputes to the person the present existence of an infectious, contagious, or loathsome disease; 3. Tends directly to injure the person in respect to the person's office, profession, trade, or business, either by imputing to the person general disqualifications in those respects which the office or other occupation peculiarly requires, or by imputing something with reference to the person's office, profession, trade, or business that has a natural tendency to lessen its profits; 4. Imputes to the person impotence or want of chastity; or 5. By natural consequence causes actual damage. 14-02-05. Privileged communications. A privileged communication is one made: 1. In the proper discharge of an official duty; 2. -

Why Expectation Damages for Breach of Contract Must Be the Norm: a Refutation of the Fuller and Perdue "Three Interests&Quo

Nebraska Law Review Volume 81 | Issue 3 Article 2 2003 Why Expectation Damages for Breach of Contract Must Be the Norm: A Refutation of the Fuller and Perdue "Three Interests" Thesis W. David Slawson University of Southern California Gould School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation W. David Slawson, Why Expectation Damages for Breach of Contract Must Be the Norm: A Refutation of the Fuller and Perdue "Three Interests" Thesis, 81 Neb. L. Rev. (2002) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol81/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. W. David Slawson* Why Expectation Damages for Breach of Contract Must Be the Norm: A Refutation of the Fuller and Perdue "Three Interests" Thesis TABLE OF CONTENTS 840 I. Introduction .......................................... Principal Institutions in a Modern Market II. The 843 Economy in Which Contracts Are Used ................ A. The Institution of the Economic Market: Contracts 843 as Bargains ....................................... Institution of Credit and Finance: Contracts as B. The 845 Property .......................................... 846 the Institutions' Needs ....................... III. Meeting 846 A. Providing a Remedy for Every Breach ............. Contracts Enforceable as Soon as They Are B. Making 847 M ade ............................................. Has Compensating the Injured Party for What He C. 848 ost ............................................... L 848 Damages Under the Expectation Measure ...... 1. 849 2. Damages Under the Reliance Measure ......... 849 a. -

Reliance and Contract Breach

RELIANCE AND CONTRACT BREACH JIM LEITZEL* I INTRODUCTION Actions taken in reliance on a contract, and court protection of such reliance in the event of a breach, have been analyzed from both legal and economic perspectives.' This article compares the legal and economic approaches to contractual reliance and develops a model for examining the protection of expenditures in reasonable reliance. The protection of reasonable reliance potentially involves circular arguments: Courts will protect the amount of reliance in which a reasonable person would engage, but a reasonable person would rely up to the extent that courts will protect.2 This article shows that the protection of reasonable reliance may be well defined, despite the potential circularity. The economic analysis that has been done on contractual reliance has noted that the protection of reliance expenditures, in the event of a breach, may render such expenditures riskless from the viewpoint of the party engaging in the reliance. 3 Since reliance expenditures are inherently risky, 4 their protection may result in overreliance from society's point of view. Overreliance can be avoided if contractual damages are invariant with respect to reliance. 5 Damage "measures can be interpreted as invariant with respect to reliance by limiting recovery on the basis of reliance to costs that are reasonably incurred." 6 This interpretation of damages, however, is subject to the circularity problem inherent in reasonableness standards. This article uses the bilateral contract 7 as the context for the examination of reliance. This article focuses on the different answers provided by the Copyright © 1989 by Law and Contemporary Problems * Visiting Associate Professor of Economics, Duke University. -

Practice Hypotheticals Contracts

Practice Hypotheticals Contracts Evaluation Sheet: “Amy and the Convertible” 1. Threshold question: Was there a contract? Need to identify the overriding question of whether enforceable promises were made. Here there was an exchange of promise to wash and wax a car for ten weeks and a promise to pay $600. 2. If so, what kind of contract? Is it a contract for the sale of goods or services? Need to identify the nature of the parties’ agreement to determine the rule of law to apply: whether the UCC or common law. Since the nature of the agreement is one for personal services (washing the car) and not a transaction in goods, the common law is applicable 3. What are Ben’s damages? General rule: Every breach of contract entitles the aggrieved party to sue for damages. The general theory of damages in contract actions is that the injured party should be placed in the same position as if the contract had been properly performed, at least so far as money can do this. Compensatory damages are designed to give the plaintiff the benefit of his bargain. Expectation damages Rule: This interest represents the “benefit of the bargain” and would include all that Ben expected to earn over the course of the contract. It is what the injured party had expected to receive under the contract “but for” the breach, less expenses saved by not having to perform. Application: Here, Ben would have earned $600 over the life of the contract, the amount she promised to pay him. He said he needed to spend $50 for supplies, so $550 was pure profit. -

Survival of Claims for and Against Executors and Administrators Alvin E

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 19 | Issue 3 Article 1 1931 Survival of Claims For and Against Executors and Administrators Alvin E. Evans University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Evans, Alvin E. (1931) "Survival of Claims For and Against Executors and Administrators," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol19/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KENTUCKY LAW JOURNAL Volume XIX MIARCH, 1931 Number 3. SURVIVAL OF CLAIMS FOR AND AGAINST EXECUTORS AN[Y ADMINISTRATORS The unfortunate condition of our law regarding the sur- vival of claims both against and in favor of the personal repre- sentative has been frequently remarked upon.' It is arguable that a policy which would support a general survival of claims in favor of a personal representative would not exist where the situation is reversed, and the wrongdoer has died in the lifetime of the claimant. The action of trespass was related to criminal appeals, and since a man cannot be punished in his grave, this action did not survive under the common law. To the extent then, that a recovery is vindictive, the maxim that personal actions die with the person might be held to support a desirable policy. -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 .............................................................................................. -

Chapter 9 Topics in the Economics of Contract Law I. Remedies As

Chapter 9 Topics in the Economics of Contract Law I. Remedies as incentives A. Alternative remedies Different remedies create different incentives for the parties to a contract. Our focus is how different remedies affect the incentives each party has to act in an economically efficient manner. 1. Expectation damages Perfect expectation damages (PED) are meant to leave the promisee indifferent between performance and nonperformance of the contract. The baseline is value to promisee if contract was performed. Damages then are equal to the difference between the net value of performance of the contract and no contract . 2. Reliance damages In this case, the injury that is caused by breach focuses on the costs the promisee has incurred as a result of relying on the contract. As such, perfect reliance damages (PRD) are meant to leave the promisee indifferent between no contract and breach of the contract. The baseline is no contract. Damages then are equal to the promisee’s net reliance costs. 3. Opportunity cost damages In this case, the injury that is caused by breach focuses on the costs the promisee has incurred as a result of foregoing alternative contracts. As such, perfect opportunity cost damages (POCD) are meant to leave the promisee indifferent between breach of the contract and performance of the next best contract. The baseline is value to promisee of the next best contract. Damages then are equal to difference between the net value of performance of the next best contract and no contract. 4. The typical relationship between PED, POCD and PRD and the problem of subjective value a. -

The Phantom Reliance Interest in Tort Damages

The Phantom Reliance interest in Tort Damages MICHAEL B. KELLY* TABLE OF CONTENTS L INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 169 IL THE RELIANCE INTEREST IN MISREPRESENTATION .............................................. 171 III. RELIANCE IN PERSONAL INJURY CASES ............................................................... 176 IV. WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN? ....................................... ... .... .... .... .... ... ..... ... .... .... .. 189 I. INTRODUCTION The reliance interest has fascinated me for some time.' As a measure of damages for breach of contract,2 it seems theoretically unjustified and flawed in its implementation. In theory, it requires compensation for lost opportunities? In practice, such compensation is rarely provided'- * Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. J.D. 1983, B.G.S. 1975, University of Michigan; M.A. 1980, University of Illinois. 1. Michael B. Kelly, The Phanton Reliance Interest in Contract Damages, 1992 WIS. L. REv. 1755. 2. My focus has been on contracts, full-fledged bargains, rather than promissory estoppel or other instances where the reliance interest might be applied. Much of my criticism of the reliance interest has been limited to this context. This Article will expand somewhat the scope of my criticism. 3. L.L. Fuller & William R. Perdue, Jr., The Reliance Interest in Contract Damages: 1, 46 YALE LJ. 52, 55, 60-61 (1936); Mark Pettit, Jr., PrivateAdvantage and Public Power: Reexamining the Expectation and Reliance Interests in Contract Damages, 38 HASTINGS L.J 417,420-21 (1987). unless one counts the expectation interest as a proxy for opportunities lost in reliance on a promise.5 In theory, it justifies recoveries that may exceed expectation.6 Yet, even its progenitors refused to endorse that implication.7 Why, then, does the reliance interest have continuing appeal? One explanation has emerged from discussions with academics: the reliance interest seems apt to some because it resembles tort remedies. -

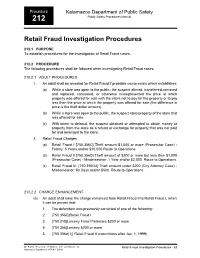

Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures

Procedure Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety Public Safety Procedures Manual 212 Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures 212.1 PURPOSE To establish procedures for the investigation of Retail Fraud cases. 212.2 PROCEDURE The following procedures shall be followed when investigating Retail Fraud cases. 212.2.1 ADULT PROCEDURES 1. An adult shall be arrested for Retail Fraud if probable cause exists which establishes: (a) While a store was open to the public, the suspect altered, transferred, removed and replaced, concealed, or otherwise misrepresented the price at which property was offered for sale with the intent not to pay for the property or to pay less than the price at which the property was offered for sale (the difference in price is the theft dollar amount). (b) While a store was open to the public, the suspect stole property of the store that was offered for sale. (c) With intent to defraud, the suspect obtained or attempted to obtain money or property from the store as a refund or exchange for property that was not paid for and belonged to the store. 2. Retail Fraud Charges (a) Retail Fraud I [750.356C] Theft amount $1,000 or more (Prosecutor Case) - Felony: 5 Years and/or $10,000 Route to Operations. (b) Retail Fraud II [750.356D] Theft amount of $200 or more but less than $1,000 (Prosecutor Case) - Misdemeanor: 1 Year and/or $2,000. Route to Operations. (c) Retail Fraud III- [750.356D4] Theft amount under $200 (City Attorney Case) - Misdemeanor: 93 Days and/or $500. Route to Operations 212.2.2 CHARGE ENHANCEMENT (a) An adult shall have the charge enhanced from Retail Fraud II to Retail Fraud I, when it can be proven that: 1.