Strategic Rail Authority Passenger Rail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 185 Feb 2020 SPECIAL FEATURE on HOW the LATEST

Issue 185 ● Feb 2020 www.railfuture.org.uk/East+Anglia twitter.com/RailfutureEA Railfuture campaigns for better services over a bigger railway (passengers + freight) Join us for £20 per year www.railfuture.org.uk/join SPECIAL FEATURE ON HOW THE LATEST TRAIN TECHNOLOGY CAN BENEFIT PASSENGERS Image reproduced courtesy of Petards Rail Technology— www.petards.com Inside this edition of RAIL EAST... • East West Rail - Progress at last! • Station footfall for 2018/19 • Look back over last 10 years • Easy Stations — the winners • What we expect in the next 10 • A giant leap for train technology • Cambridge South consultation • Whittlesford audit improvements RAIL EAST 185 — FEBRUARY 2020 Railfuture East Anglia www.railfuture.org.uk TOPICS COVERED IN THIS ISSUE OF RAIL EAST In this issue’s 24 pages we have fewer (but longer) articles than last time and only five authors. Contributions are welcome from readers. Contact info on page 23. Chair’s thoughts – p.3 Easy Stations winners announced – plus how do our stations compare with Germany’s? And a snapshot of progress with platform development work at Stevenage East West Rail big announcement (1) – p.5 Preferred route for the central section is finally published – now the serious work begins East West Rail big announcement (2) – p.7 Progress on the western section, as Transport & Works Order is published and work on the ground is set to start Another critical consultation – Cambridge South – p.8 Momentum builds on this key item of passenger infrastructure – Railfuture’s wish- list for the new station -

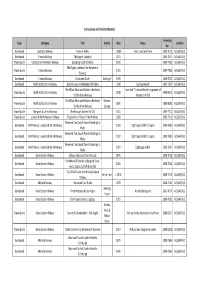

Serial Asset Type Active Designation Or Undertaking?

Serial Asset Type Active Description of Record or Artefact Registered Disposal to / Date of Designation, Designation or Number Current Designation Class Designation Undertaking? Responsible Meeting or Undertaking Organisation 1 Record YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings 1995/01 Network Rail 22/09/1995 Designation produced for Great Western Rly Co or its Infrastructure Ltd associated Companies between 1833 and 1859 [operational property] 2 Disposed NO The Gooch Centrepiece 1995/02 National Railway 22/09/1995 Disposal Museum 3 Replaced NO Classes of Record: Memorandum and Articles 1995/03 N/A 24/11/1995 Designation of Association; Annual Reports; Minutes and working papers of main board; principal subsidiaries and any sub-committees whether standing or ad hoc; Organisation charts; Staff newsletters/papers and magazines; Files relating to preparation of principal legislation where company was in lead in introducing legislation 4 Disposed NO Railtrack Group PLC Archive 1995/03 National Railway 24/11/1995 Disposal Museum 5 YES Class 08 Locomotive no. 08616 (formerly D 1996/01 London & 22/03/1996 Designation 3783) (last locomotive to be rebuilt at Birmingham Swindon Works) Railway Ltd 6 Record YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings 1996/02 BRB (Residuary) 22/03/1996 Designation produced for Great Western Rly Co or its Ltd associated Companies between 1833 and 1859 [Non-operational property] 7 Record YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings 1996/02 Network Rail 22/03/1996 Designation produced for Great Western Rly Co or its Infrastructure -

Competitive Tendering of Rail Services EUROPEAN CONFERENCE of MINISTERS of TRANSPORT (ECMT)

Competitive EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT Tendering of Rail Competitive tendering Services provides a way to introduce Competitive competition to railways whilst preserving an integrated network of services. It has been used for freight Tendering railways in some countries but is particularly attractive for passenger networks when subsidised services make competition of Rail between trains serving the same routes difficult or impossible to organise. Services Governments promote competition in railways to Competitive Tendering reduce costs, not least to the tax payer, and to improve levels of service to customers. Concessions are also designed to bring much needed private capital into the rail industry. The success of competitive tendering in achieving these outcomes depends critically on the way risks are assigned between the government and private train operators. It also depends on the transparency and durability of the regulatory framework established to protect both the public interest and the interests of concession holders, and on the incentives created by franchise agreements. This report examines experience to date from around the world in competitively tendering rail services. It seeks to draw lessons for effective design of concessions and regulation from both of the successful and less successful cases examined. The work RailServices is based on detailed examinations by leading experts of the experience of passenger rail concessions in the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands. It also -

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit Contents How to install ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Technical information ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Liveries .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Cab guide ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Keyboard controls ...................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Features .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Global System for Mobile Communication-Railway (GSM-R) ............................................................................. 18 Registering .......................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Deregistering - Method 1 ............................................................................................................................................ -

St.Paul's Church, Hills Rd, Cambridge Is the New Venue for Our Next Branch Meeting on Saturday, 7 December at 14.00 Hrs

ISSUE160 December 2013 Internet at www.railfuture.org.uk www.railfuture.org.uk/east html St.Paul's Church, Hills Rd, Cambridge is the new venue for our next Branch Meeting on Saturday, 7 December at 14.00 hrs. The main topic will be Cambridge Railway Station and its development within the larger scheme for CB1 submitted by Brookgate Developments. Our Guest Speaker will Geraint Hughes of Greater Anglia Railways with, hopefully, contributions from a representative of Brookgate. There will be plenty of opportunity for questions. The focus will not be on the Brookgate scheme per se, but on its relationship to the railway and its customers. So do join us for what promises to be a stimulating meeting. 1 NEWS Halesworth Station Footfall Count 2013 Railfuture East Anglia joined up with the East Suffolk Travellers' Association at Halesworth Station on October 17th to count the passengers using trains and buses from the station, Reports, Mike Farahar. The numbers were up an impressive 43% compared to the same time last year following the introduction of an hourly train service on the northern part of the Ipswich to Lowestoft line following investment in the passing loop at Beccles, and the improvements to the bus service between Halesworth and Southwold. Every train was surveyed,from 05.56 to 23.10 and 337 passengers boarded or alighted, compared to 235 in 2012. The number of bus transfers was also encouraging but would benefit from additional advertising including marketing the possibility of using the bus from Bungay as a feeder service into the trains. -

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

Performance Monitoring Report on NATIONAL RAIL

Performance monitoring report on NATIONAL RAIL PASSENGER SERVICES IN THE LONDON AREA Quarter 1 2002-03 (April to June 2002) Prepared by LTUC Research and Policy Team 6 Middle Street London EC1A 7JA October 2002 CONTENTS Section 1 Public performance measure (PPM) Section 2 Lost minutes Section 3 National passenger survey (NPS) (not reported this quarter) Section 4 Passengers in excess of capacity (PIXC) (not reported this quarter) Section 5 Passenger complaints (not reported this quarter) Section 6 Impartial retailing survey (not reported this quarter) Section 7 Glossary and definitions Annex A PPM results for Quarter 1 2001-02 (table) Annex B PPM results for Quarter 1 2001-02 (chart) Annex C 3-year PPM trends – all trains (chart) Annex D 3-year PPM trends – London and south east peak trains (chart) Annex E Lost minutes – Quarter 1 2002-03 (table) Annex F NPS results (not reported this quarter) Annex G Narrative commentaries supplied by the following operators : c2c, Chiltern, Connex South Eastern, First Great Eastern, Gatwick Express, Silverlink, South West Trains, Thameslink, West Anglia Great Northern, Anglia, First Great Western, Great North Eastern, Midland Mainline and Virgin West Coast. OVERVIEW OF QUARTER • Reliability of most London and south east operators has continued to improve but was still below the levels reached prior to the aftermath of the Hatfield derailment. • Wide variations between operators continued, ranging from 9% of trains delayed or cancelled to 24%. • Nearly all operators performed relatively well in weekday peaks, with only a slight decrease on c2c, First Great Eastern and Silverlink. • Longer-distance operators’ performance was 1.5% better than in the previous year and 2% better than in the preceding quarter. -

Invitation to Tender

Greater Anglia Franchise - Invitation to Tender Greater Anglia Franchise Invitation to Tender 21 April 2011 Page 1 Greater Anglia Franchise - Invitation to Tender TABLE OF CONTENTS IMPORTANT NOTICE................................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 6 1.1 PURPOSE OF THIS INVITATION TO TENDER ....................................................................................................... 6 1.2 SCOPE OF THE GREATER ANGLIA FRANCHISE .................................................................................................. 6 1.3 THE DEPARTMENT'S OBJECTIVES FOR THE GREATER ANGLIA FRANCHISE....................................................... 6 1.4 CLOSING DATE FOR BIDS.................................................................................................................................. 6 SECTION 2: INFORMATION AND INSTRUCTIONS TO BIDDERS............................................................... 7 2.1 FRANCHISING TIMETABLE AND PROCESS ......................................................................................................... 7 2.2 RESTRICTION ON COMMUNICATIONS/PRESS RELEASES ETC DURING FRANCHISE COMPETITION ...................... 7 2.3 CHANGES IN CIRCUMSTANCES ........................................................................................................................ -

Penalty Fares Scheme Template

Penalty fares scheme – c2c rail limited 1 Introduction 1.1 c2c rail limited, give notice, under rule 3.2 of the SRA’s Penalty Fares Rules 2002, that we want to introduce a penalty fares scheme with effect from a date yet to be confirmed. This document describes our penalty fares scheme for the purposes of rule 3.2 b. 1.2 We have decided to introduce a penalty fares scheme in this area because 1. Although the vast majority of our stations is gated, it is still possible to access our railway system without a ticket and/or travel to a destination that is past the validity of tickets held and leave via a non-fully gated station. 2. The Penalty Fares Scheme is seen as a supplant to existing method of dealing with individuals who do not hold valid tickets for their entire journeys. 3. The Penalty Fares Scheme is seen as a visual deterrent, i.e. via the posters at all stations, that c2c rail limited is committed to reduce to the absolute minimum fraudulent travel on our trains. 1.3 We have prepared this scheme taking account of the following documents. • The Railways (Penalty Fares) Regulations 1994. • The Penalty Fares Rules 2002. • Strategic Rail Authority Penalty Fares Policy 2002. 1.4 In line with rule 3.2, we have sent copies of this scheme to: • The Strategic Rail Authority; • London Transport Users Committee • Rail Passengers Committee for Eastern England 2 Penalty fares trains 2.1 For the purposes of this scheme, all the trains that we operate on the c2c route will be penalty fares trains. -

Railway Byelaws

RAILWAY BYELAWS Made under Section 219 of the Transport Act 2000 by the Strategic Rail Authority (the “Authority”) and confirmed under Schedule 20 of the Transport Act 2000 by the Secretary of State for Transport on 22 June 2005 for regulating the use and working of, and travel on or by means of, railway assets, the maintenance of order on railway assets and the conduct of all persons while on railway assets (the “Byelaws”). CONTENTS Introduction: Railway Byelaws – Why they help us to help you RAILWAY BYELAWS Conduct and behaviour 1. Queuing 2. Potentially dangerous items 3. Smoking 4. Intoxication and possession of intoxicating liquor 5. Unfit to be on the railway 6. Unacceptable behaviour 7. Music, sound, advertising and carrying on a trade 8. Unauthorised gambling Equipment and safety 9. Stations and railway premises 10. Trains 11. General safety 12. Safety instructions 1 Control of premises 13. Unauthorised access and loitering 14. Traffic signs, causing obstructions and parking 15. Pedestrian-only areas 16. Control of animals Travel and fares 17. Compulsory ticket areas 18. Ticketless travel in non-compulsory ticket areas 19. Classes of accommodation, reserved seats and sleeping berths 20. Altering tickets and use of altered tickets 21. Unauthorised buying or selling of tickets 22. Fares offences committed on behalf of another person Enforcement and interpretation 23. Name and address 24. Enforcement (1) Offence and level of fines (2) Removal of persons (3) Identification of an authorised person (4) Notices (5) Attempts (6) Breaches by authorised persons 25. Interpretation (1) Definitions (2) Introduction, table of contents and headings (3) Plural (4) Gender 2 26. -

Class 168/170/171 Enhancement Pack

Class 168/170/171 Enhancement Pack Contents How to install ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Liveries ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Class 168 ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Class 170 ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Class 171 .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Keyboard controls ................................................................................................................................. 15 Features .................................................................................................................................................... 16 Voith T211rzze hydraulic transmission ..................................................................................... 17 1st stage - torque converter ...................................................................................................... 17 2nd stage - fluid coupling ........................................................................................................... 17 Wheelslip Protection -

Railway Organisations 20 SEPTEMBER 1999

RESEARCH PAPER 99/80 Railway Organisations 20 SEPTEMBER 1999 The Research Paper provides reference information about the rail industry. Part I lists the names and addresses of the train operating companies and gives some background detail about the franchise award. Part II lists other organisations involved in the industry. It updates Research Paper 97/72 The Railway Passenger Companies. Fiona Poole and Andrew Dyer BUSINESS AND TRANSPORT SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: 99/65 The Food Standards Bill [Bill 117 of 1998-99] 18.06.99 99/66 Kosovo: KFOR and Reconstruction 18.06.99 99/67 The Burden of Taxation 25.06.99 99/68 Financial Services and Markets Bill [Bill 121 of 1998-99] 24.06.99 99/69 Economic Indicators 01.07.99 99/70 The August Solar Eclipse 30.06.99 99/71 Unemployment by Constituency - June 1999 14.07.99 99/72 Railways Bill [Bill 133 of 1998-99] 15.07.99 99/73 The National Lottery 27.07.99 99/74 Duty-free shopping 22.07.99 99/75 Economic & Monetary Union: the first six months 12.08.99 99/76 Unemployment by Constituency - July 1999 11.08.99 99/77 British Farming and Reform of the Common Agriculture Policy 13.08.99 99/78 By-elections since the 1997 general election 09.09.99 99/79 Unemployment by Constituency - August 1999 15.09.99 Research Papers are available as PDF files: • to members of the general public on the Parliamentary web site, URL: http://www.parliament.uk • within Parliament to users of the Parliamentary Intranet, URL: http://hcl1.hclibrary.parliament.uk Library Research Papers are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff.