CME Report 4—Preparedness For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland (LLR) Local Digital Roadmap 2016 - 2021 Contents

Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland (LLR) Local Digital Roadmap 2016 - 2021 Contents Foreword for Local Digital Roadmap 2 5. Capabilities 38 5.1 Paper free at Point of Care groups 1. Introduction 4 of capabilities 38 1.1 Our Journey in Delivering the 5.1.1 Records, assessments and plans 38 Five Year Forward View and Personalised 5.1.2 Transfers of care 41 Health and Care 2020 4 5.1.3 Orders and results management 43 1.2 Overview of Organisations Covered 6 5.1.4 Medicines management and optimisation 43 1.3 Sustainability and Transformation Plan 5.1.5 Decision support 45 (STP) Alignment 6 5.1.6 Remote care 46 1.3.1 Better Care Together (BCT) 7 5.1.7 Asset and resource optimisation 49 1.4 Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland (LLR) 5.2 16/17-17/18 Universal capabilities 54 Context 8 5.3 Capabilities Delivery Plan 55 2. A vision for digitally-enabled 6. Information Sharing 56 transformation 19 6.1 Information Sharing Strategy 56 6.2 Information Governance 56 6.3 Interoperability Strategy 57 3. Baseline Position 20 3.1 Current Technology Landscape 20 7. Infrastructure 58 3.1.1 Data Sharing 20 3.1.2 Patient Access 21 3.1.3 Electronic Prescriptions 21 8. Minimising risks arising from 3.1.4 Electronic Clinical Correspondence 21 technology 63 3.1.5 Business Intelligence 21 3.1.6 System Access 22 9. Timescales and Delivery of the 3.1.7 Pathways 22 Local Digital Roadmap 64 3.1.8 Patient Focused Apps 22 2016/17 64 3.2 Rate limiting factors 23 2017/18 66 2018/19 68 4. -

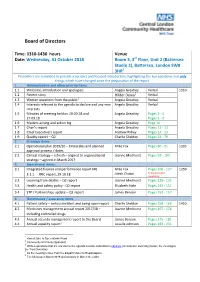

Board of Directors

Board of Directors Time: 1310-1430 hours Venue Date: Wednesday, 31 October 2018 Room 3, 3rd Floor, Unit 2 (Battersea Studio 2), Battersea, London SW8 3HR1 Presenters are reminded to provide a succinct and focused introduction, highlighting the key questions and only things which have changed since the preparation of the report 1 Administrative and other priority items 1.1 Welcome, introduction and apologies: Angela Greatley Verbal 1310 2 1.2 Patient story Hilder Dewa Verbal 1.3 Written questions from the public3 Angela Greatley Verbal 1.4 Interests relevant to the agenda to declare and any new Angela Greatley Verbal interests 1.5 Minutes of meeting held on 20.09.18 and Angela Greatley Pages 3 - 4 27.09.18 Pages 5 - 9 1.6 Matters arising and action log Angela Greatley Page 10 1.7 Chair’s report Angela Greatley Pages 11 - 13 1.8 Chief Executive’s report Andrew Ridley Pages 14 - 23 1.9 Quality report – Q2 Charlie Sheldon Pages 24 - 79 2 Strategic items 2.1 Operational plan 2019/20 – timescales and planned Mike Fox Pages 80 - 91 1335 approval process / dates 2.2 Clinical strategy – refresh – aligned to organisational Joanne Medhurst Pages 92 - 105 strategy – agreed in March 2017 3 Operational items 3.1 Integrated finance and performance report M6 Mike Fox Pages 106 - 127 1350 Jitesh Chotai To be provided 3.1.1 FRIC report, 29.10.18 separately 4 3.2 Learning from deaths – Q2 report Joanne Medhurst Pages 128 - 131 3.3 Health and safety policy - Q2 report Elizabeth Hale Pages 132 - 151 3.4 STP / Partnerships update – Q2 report James Benson Pages -

The World's Leading AI in Medicine Summit

The world’s leading AI in medicine summit Wednesday 5th February 2020 London, UK http://www.intelligenthealth.ai/ The mission? Intelligent Health, in partnership with NHSX, will bring the global AI and health community to London in February 2020 for a one-day event to advance discussions on how to apply AI and drive technological collaboration in healthcare. 800+ delegates will join industry leading global speakers for an in-depth look at AI within the UK health market, how it can be used to prevent and solve some of the world’s greatest healthcare problems, improve the health of the human race and set the UK AI agenda in healthcare for 2020 and beyond. What’s on? Jam-packed day of health tech goodness! Practical, real-world AI use cases, announcements from tech giants, hear from health tech transformers of tomorrow and a showcase of innovation, followed by 10 collaborative hands-on sessions tackling live digital health challenges. Be ready to think like a physician and code like a developer. Wednesday 5th February 2020 07:30 REGISTRATION Session One 09:00 – 11:00 09:00 WELCOME Inspired Minds Denise Tack, Strategy Director - Health, Inspired Minds WELCOME NHSX Tara Donnelly, CDIO, NHSX WELCOME and chairperson’s opening remarks Sameena Ali-Khan, Television Presenter, ITV 09:20 HEADLINER Leading digital change, interoperability and innovation – how the NHS will work more effectively with larger tech firms and digital health innovators Tara Donnelly, CDIO, NHSX 09:45 HEADLINER Maximising our digital infrastructure for a 21st century workforce Frank Hester, Founder and CEO, The Phoenix Partnership 10:10 HEADLINER Inside Pandora's Black Box: Understanding decision-making in diagnostic AI and its implications for clinician skills Dr. -

Management Stakeholders

Hyperglycaemia in acute coronary syndromes: management Stakeholders 15 Healthcare 2gether NHS Foundation Trust 3M Health Care UK 4Children 5 Boroughs Partnership NHS Foundation Trust A.Menarini Pharma U.K. S.R.L. Abbott Diabetes Care Abbott Diagnostics Division Abbott Diagnostics Division Abbott Laboratories Abbott Vascular Devices Abbott Vascular Devices AbbVie AbbVie Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University NHS Trust Achieving for Children Action Heart Action on Addiction Action on Hearing Loss Action on Smoking & Health Action on Smoking and Health Addaction Addenbrookes Hospital Addiction Today ADFAM Adults Strategy and Commissioning Unit Advisory Committee for Community Dentistry Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Afiya Trust African Health Policy Network Aintree University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Alcohol and Drug service Alcohol Focus Scotland Alcohol Use Disorders: Clinical Management Guideline Development Group Alcoholics Anonymous Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust Alere Alere Alere International Alere Ltd Alere Ltd Alkermes Inc All Party Parliamentary Group on Vascular Disease Allergan Ltd UK Alliance Boots plc Allocate Software PLC Alpha Medical American Medical Systems Inc. American Medical Systems Inc. American Medical Systems UK Ltd AMORE health Ltd AMORE health Ltd AMORE Studies Group AMORE Studies Group Aneurin Bevan University Health Board anglia community leisure Anglia University Anglian Community Enterprise Ark Therapeutics Ltd Arrhythmia Alliance Arrowe Park Hospital Assocation of NHS Occupational Physicians -

Hydroxychloroquine for Prevention of COVID-19 Mortality: a Population-Based Cohort Study

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.04.20187781; this version posted September 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY 4.0 International license . Hydroxychloroquine for prevention of COVID-19 mortality: a population-based cohort study Christopher T Rentsch1*&, Nicholas J DeVito2*, Brian MacKenna2*, Caroline E Morton2*, Krishnan Bhaskaran1, Jeremy P Brown1, Anna Schultze1, William J Hulme2, Richard Croker2, Alex J Walker2, Elizabeth J Williamson1, Chris Bates3, Seb Bacon2, Amir Mehrkar2, Helen J Curtis2, David Evans2, Kevin Wing1, Peter Inglesby2, Rohini Mathur1, Henry Drysdale2, Angel YS Wong1, Helen I McDonald1, Jonathan Cockburn3, Harriet Forbes1, John Parry3, Frank Hester3, Sam Harper3, Liam Smeeth1, Ian J Douglas1, William G Dixon4, Stephen JW Evans1, Laurie Tomlinson1†, Ben Goldacre2† 1 Electronic Health Records Research Group, Faculty of Epidemiology and Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London WC1E 7HT 2 The DataLab, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Woodstock Rd, Oxford OX2 6GG 3 The Phoenix Partnership, 129 Low Lane, Horsforth, Leeds LS18 5PX 4 Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL *These authors contributed equally to this work †Joint principal investigators &corresponding: [email protected]; @DarthCTR NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. 1 medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.04.20187781; this version posted September 9, 2020. -

2901121 Safer Hospitals, Safer Wards

The NHS England Putting business plan for Patients First 2013/14 – 2015/16 SUPPORTING, DEVELOPING AND ASSURING THE DIRECT COMMISSIONING COMMISSIONING SYSTEM PARTNERSHIP STRATEGY, FOR RESEARCH Achieving an AND SAFER HOSPITALS INNOVATION integrated digital FOR OUTCOMES SAFER WARDS careEMERGENCY record AND PREPAREDNESS QUALITY GROWTH WORLD WORLD CLASS CLASS CUSTOMER CLINICAL SERVICE: DEVELOPING AND INFORMATION, CUSTOMER PROFESSIONAL TRANSPARENCY COMMISSIONING AND SUPPORT SERVICE: LEADERSHIP PARTICIPATION UNITS INFORMATION, PEOPLE ACCESSING TRANSPARENCY THEIR AND DATA PARTICIPATION RIGHT DATA, NHS NUMBER: RIGHT PLACE, RIGHT TIME INTEGRATING CARE COMMUNITY OF PRACTICE High quality care for all, now and for future generations NHS England INFORMATION READER BOX Directorate Medical Operations Patients and Information Nursing Policy Commissioning Development Finance Human Resources Publications Gateway Reference: 00201 Document Purpose Guidance and launch of the Safer Hospitals, Safer Wards Technology Fund Document Name Safer Hospitals, Safer Wards: Achieving an Integrated Digital Care Record Author NHS England Publication Date 01 July 2013 Target Audience Foundation Trust CEs, Foundation Trust Board Chairs, NHS Trust CEs, NHS Trust Board Chairs, Medical Directors, Directors of Nursing, Directors of Finance, NHS England Regional Directors, NHS England Area Directors Additional Circulation List CCG Clinical Leaders, CCG Accountable Officers, CSU Managing Directors, Local Authority CEs, Directors of Adult SSs, Academic Health Science Networks Description This document sets out the benefits case for adopting safe digital record keeping as a precursor to achieving integrated digital care records across the health and care system. It provides further details and support for NHS Trusts, including Foundation Trusts, relating to their progress from paper to paper-light and ultimately paperless record keeping. -

Stroke (QS Update) Stakeholders 3M Health Care UK Abbott Molecular

Stroke (QS update) Stakeholders 3M Health Care UK Abbott Molecular Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists Adults Strategy and Commissioning Unit African Health Policy Network Age Related Diseases and Health Trust Age UK AGILE: Chartered Physiotherapists working with Older People Aintree University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Airedale NHS Trust Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust All Wales Stroke Dietitians Group Allergan Ltd UK Allocate Software PLC AMORE health Ltd AMORE Studies Group Anglia Stroke and Heart Network Anglian Community Enterprise AntiCoagulation Europe Anticoagulation Specialist Association Apetito Ltd Applied Medical Applied Medical UK Ltd Arrhythmia Alliance Arrowe Park Hospital Association for Continence Advice Association for Dance Movement Psychotherapy UK Association of Ambulance Chief Executives Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland Association of British Healthcare Industries Association of British Insurers Association of British Neurologists Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Neurology Association of Clinical Pathologists Association of Dance Movement Therapy UK Association of Directors of Adult Social Services Association of Optometrists Association of Professional Music Therapists Astrazeneca UK Ltd Atrial Fibrillation Association Autism in Mind Avon, Gloucestershire and Wiltshire Strategic Health Authority Bard Limited Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Bayer HealthCare Bayer plc Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire -

Board Meeting

Board Meeting A virtual meeting will be held Wednesday, 29 July 2020 commencing at 1:00pm If you are unable to attend please notify Keith Eales on 01202 277008. Yours sincerely, Andy Willis Chairman PART 1 Lead Paper Time 1 Apologies AW Verbal 1:00 2 Declarations of interests in relation to agenda AW Verbal items 3 Patient Story TP Paper 4 Minutes: 24 June 2020 - to approve AW Paper 5 Matters Arising – to review progress AW Paper 6 Chairman’s Report - to receive an update. AW Verbal Strategy Items 7 Fit for the Future Programme KD Paper To note the report. Current Affairs and Operational Performance 8 Chief Executive’s Report EY Verbal 1:45 To note the update. 9 Trust Board Integrated Corporate Dashboard KD Paper 2:00 To note performance for June. 10 Trust Finance Report for June 2019 MM Paper 2:15 To the report. 1 11 Dorset Care Record Update MM Paper 2:30 To note the report. Regulatory and Governance Matters 12 Reports from Committee Chairs 2:40 a) Appointments and Remuneration AW Verbal Committee: 8 July 2020 b) Mental Health Legislation Assurance SM Paper Committee: 8 July 2020 c) Audit Committee: 15 July 2020 TP Paper d) Quality Governance Committee:15 DB Paper July 2020 13 Annual Report of the Mental Health SM Paper 2:50 Legislation Assurance Committee 2019/20 To note the report. 14 Appointment of a Senior Independent AW Paper 3.00 Director To make an appointment. Other Matters 15 Questions from Governors on matters on the AW Verbal agenda What went well, what could be better? 15 Next Meeting: 1.00pm, Wednesday 30 AW Verbal 3:20 September 2020 2 Agenda Item 3 Patient Story Part 1 Board Meeting 29 July 2020 Author Janine Coletta, Patient Experience Facilitator Purpose of Report To consider the patient experience of our service Executive Summary The report is being submitted to the Board for consideration, reflection and to highlight the positive experience of care received from Langdon Ward (now Colmers Ward) at Bridport Hospital, and how this has impacted both the patient and the patient’s family. -

23 November 2020 Special Meeting Board of Trustees - 1

23 November 2020 Special Meeting Board of Trustees - 1 REPORTS OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES The following reports were presented by Russ Kridel, MD, Chair: 1. 2019 GRANTS AND DONATIONS Informational report; no reference committee hearing. HOD ACTION: FILED This informational financial report details all grants or donations received by the American Medical Association during 2019. American Medical Association Grants & Donations Received by the AMA For the Year Ended December 31, 2019 Amounts in thousands Amount Funding Institution Project Received Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Midwest Small Practice Care Transformation Research $ 4 (subcontracted through Northwestern University) Alliance Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Insurance Expansion and Physician Distribution 49 (subcontracted through RAND Corporation) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Engaging Physicians to Strengthen the Public Health 18 System and Improve the Nation's Public Health Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Building Healthcare Provider Capacity to Screen, Test, 182 (subcontracted through American College of Preventive and Refer Disparate Populations with Prediabetes Medicine) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Preventing Heart Attacks and Strokes in Primary Care 117 (subcontracted through National Association of Community Health Centers, Inc.) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Transforming Clinical Practices Initiative — Support 467 and Alignment Networks Government Funding 837 American Heart Association, Inc. -

BOT Report 02-Nov-20.Docx

REPORT OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES B of T Report 2, November 2020 Subject: Update on Corporate Relationships Presented by: Russ Kridel, MD, Chair 1 PURPOSE 2 3 The purpose of this informational report is to update the House of Delegates (HOD) on the results of 4 the Corporate Review process from January 1 through December 31, 2019. Corporate activities that 5 associate the American Medical Association (AMA) name or logo with a company, non-Federation 6 association or foundation, or include commercial support, currently undergo review and 7 recommendations by the Corporate Review Team (CRT) (Appendix A). 8 9 BACKGROUND 10 11 At the 2002 Annual Meeting, the HOD approved revised principles to govern the American Medical 12 Association’s (AMA) corporate relationships, HOD Policy G-630.040 “Principles on Corporate 13 Relationships.” These “Guidelines for American Medical Association Corporate Relationships” were 14 incorporated into the corporate review process, are reviewed regularly, and were reaffirmed at the 15 2012 Annual Meeting. AMA managers are responsible for reviewing AMA projects to ensure they 16 fit within these guidelines. 17 18 YEAR 2019 RESULTS 19 20 In 2019, 85 new activities were considered and approved through the Corporate Review process. Of 21 the 85 projects recommended for approval, 47 were conferences or events, 10 were educational 22 content or grants, 23 were collaborations or affiliations, two were member programs, one was an 23 American Medical Association (AMA) Alliance activity and two were American Medical 24 Association Foundation (AMAF) programs (Appendix B). 25 26 CONCLUSION 27 28 The Board of Trustees (BOT) continues to evaluate the CRT review process to balance risk 29 assessment with the need for external collaborations that advance the AMA’s strategic focus. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Jesse M

CURRICULUM VITAE Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, M.D., M.P.H., FAMIA, FASA Office Address: Department of Anesthesiology Vanderbilt University Medical Center 1301 Medical Center Drive, TVC 4648 Nashville, TN 37232 Work Phone: (615) 936-5194 Work Facsimile: (615) 936-6493 Work Email: [email protected] Place of Birth: Wilmington, Delaware, USA Military Service: Commander, U.S. Navy Medical Corps (2008-2018) Veteran Status: Combat Veteran, Operation Enduring Freedom (2014) Combat Veteran, Resolute Support Mission (2015) Education: 1992-1996 Phillips Academy Andover, Andover, MA 1996-2000 B.S., Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania 2000-2004 M.D., University of Chicago - Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois 2008 Summer Program in Clinical Effectiveness, Harvard University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts 2008-2009 Masters of Public Health, Harvard University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts Postdoctoral Training: 6/2004 – 6/2005 Internship in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 6/2005 – 8/2005 Research Fellowship in Anesthesia, Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 8/2005 – 8/2008 Resident in Anesthesiology, Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 8/2008 – 8/2010 Research Fellowship in Anesthesia Informatics, Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, -

Power & Purpose

26 30 36 Jesse Ehrenfeld Grayson Schultz Keith Borden Madison’s LGBT&XYZ Magazine Advocates advancing LGBTQ health equity across our state November / December 2020 RACIAL FRAUD AT THE UW . After a trans student was outed for falsely identifying as a person of color, we look at the ways that whiteness contributes to the harm that POC experience from racial fraud p.15 FUTURE OF LGBTQ RIGHTS . What the conservative Supreme Court majority means for defending and advancing our legal protections p.48 power & purpose Dana Pellebon The co-executive director of Rape Crisis Center on creating change and making a difference in the lives of traditionally underserved people Wisconsin’s source for LGBTQ News + People + Community + Culture since 2007 As your dreAms evolve, we’re here to support you. Whether you’re buying your first car or your retirement home, American Family Insurance is with you TAKE A SMART STEP TO every step of the way, ensuring that your dreams are always protected. Colleen Frentzel, David Agent Ryan-Sukup, Agent 4407 Milton Ave 514 Ste 110Grand Canyon Dr A HEALTHY SMILE Janesville, WI 53546 [email protected] (608) 302-4101 Madison, WI 53719 [email protected] Bus: (608) 833-1717 David Ryan-Sukup, Agent 514 Grand Canyon Dr Madison, WI 53719 [email protected] (608) 833-1717 CALL TODAY (608) 241-8782 American Family Mutual Insurance Company, S.I. & its Operating Companies, American Family Insurance Company, 6000 American Parkway, Madison, WI 53783 008747 – Rev. 12/15 ©2015 – 11828218 Thank you to our Madison community for 10 amazing years of creating healthy smiles.