The Intentions of the Framers of the Australian Constitution Regarding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes

NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES X X I NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are respectfully advised that this book includes the names and images of people who are now deceased. Cover: Detail from Caroline Chisholm's portrait by Angelo Collen Hayter, oil on canvas, 1852, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG 459). Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes © Reserve Bank of Australia 2016 E-book ISBN 978-0-6480470-0-1 Compiled by: John Murphy Designed by: Rachel Williams Edited by: Russell Thomson and Katherine Fitzpatrick For enquiries, contact the Reserve Bank of Australia Museum, 65 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 <museum.rba.gov.au> CONTENTS Introduction VI Portraits from the present series Portraits from pre-decimal of banknotes banknotes Banjo Paterson (1993: $10) 1 Matthew Flinders (1954: 10 shillings) 45 Dame Mary Gilmore (1993: $10) 3 Charles Sturt (1953: £1) 47 Mary Reibey (1994: $20) 5 Hamilton Hume (1953: £1) 49 The Reverend John Flynn (1994: $20) 7 Sir John Franklin (1954: £5) 51 David Unaipon (1995: $50) 9 Arthur Phillip (1954: £10) 53 Edith Cowan (1995: $50) 11 James Cook (1923: £1) 55 Dame Nellie Melba (1996: $100) 13 Sir John Monash (1996: $100) 15 Portraits of monarchs on Australian banknotes Portraits from the centenary Queen Elizabeth II of Federation banknote (2016: $5; 1992: $5; 1966: $1; 1953: £1) 57 Sir Henry Parkes (2001: $5) 17 King George VI Catherine Helen -

JHSSA Index 2014

Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia Subject Index 1975-2014 Nos 1 to 42 Compiled by Brian Samuels The Historical Society of South Australia Inc PO Box 519 Kent Town 5071 South Australia JHSSA Subject Index 1975–2014 page 35 Subject Index 1975-2014: Nos 1 to 42 This index consolidates and updates the Subject Index to the Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia Nos 1 - 20 (1974 [sic] - 1992) which appeared in the 1993 Journal and its successors for Nos 21 - 25 (1998 Journal) and 26 - 30 (2003 Journal). In the latter index new headings for Gardens, Forestry, Place Names and Utilities were added and some associated reindexing of the entire index database was therefore undertaken. The indexing of a few other entries was also improved, as has occurred with this latest updating, in which Heritage Conservation and Imperial Relations are new headings while Death Rituals has been subsumed into Folklife. The index has certain limitations of design. It uses a limited number of, and in many instances relatively broad, subject headings. It indexes only the main subjects of each article, judged primarily from the title, and does not index the contents – although Biography and Places have subheadings. Authors and titles are not separately indexed, but they do comprise separate fields in the index database. Hence author and title indexes could be included in future published indexes if required. Titles are cited as they appear at the head of each article. Occasionally a note in square brackets has been added to clarify or amplify a title. -

Imagereal Capture

The Australian Constitution - A Centenary Assessment THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE MICHAEL KIRBY* LUCINDA'S HANDIWORK For some reason which I cannot fathom, I long believed that the SS Lucinda was a paddle-steamer plying the Murray River in the 1890s. Perhaps it was a trick of the mind: assuming that the factious politicians who refined the first effective draft of the Australian Constitution would only agree to meet on neutral territory: the water between the two principal colonies. Such an assumption would have been legally inaccurate.' But, more importantly, it was historically erroneous. The SS Lucinda actually belonged to the Queens- land Government which had generously put it at the disposal of Samuel Griffith for use in February and March 1891. The chosen delegates who climbed aboard in Sydney Harbour for its historic journey to the Hawkesbury River hammered out a draft which became, ten years later, Australia's federal Constitution.' The Committee, under Griffith, worked on a draft Bill prepared by Inglis Clark of Tasmania. Alas, Clark was laid low by influenza which was later to affect Griffith; but not before he had worked over the long Easter weekend on the revised draft to be presented to the First Convention. Clark's illness caused Griffith and his fellow draftsman, Charles Kingston of South Australia, to invite Edmund Barton to join them.3 It was an auspicious choice. Barton became very influential in the Conventions. He went on to become the first Prime Minister and, with Griffith, a member of the first High Court. This core of drafters, with a group of lawyers from all invited colonies except Western Australia and New Zealand (who had not arrived) made up the Lucinda party. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 1995 No. 154 Senate (Legislative day of Monday, September 25, 1995) The Senate met at 9 a.m., on the ex- DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, JUS- Mr. President, I intend to be brief, piration of the recess, and was called to TICE, AND STATE, THE JUDICI- and I note the presence of the Senator order by the President pro tempore ARY, AND RELATED AGENCIES from North Dakota here on the floor. I [Mr. THURMOND]. APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 1996 know that he needs at least 10 minutes The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The of the 30 minutes for this side. I just want to recap the situation as PRAYER clerk will report the pending bill. The assistant legislative clerk read I see this amendment. First of all, Mr. The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John as follows: President, the choice is clear here what Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: A bill (H.R. 2076) making appropriations we are talking about. The question is Let us pray: for the Department of Commerce, Justice, whether we will auction this spectrum off, which, according to experts, the Lord of history, God of Abraham and and State, the Judiciary and related agen- value is between $300 and $700 million, Israel, we praise You for answered cies for the fiscal year ending September 30, 1996, and for other purposes. or it will be granted to a very large and prayer for peace in the Middle East very powerful corporation in America manifested in the historic peace treaty The Senate resumed consideration of for considerably less money. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

Yet We Are Told That Australians Do Not Sympathise with Ireland’

UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE ‘Yet we are told that Australians do not sympathise with Ireland’ A study of South Australian support for Irish Home Rule, 1883 to 1912 Fidelma E. M. Breen This thesis was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Research in the Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. September 2013. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .............................................................................................. 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................. 4 Declaration ........................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. 6 ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ 7 CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................................ 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 WHAT WAS THE HOME RULE MOVEMENT? ................................................................. 17 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE .................................................................................... -

The Ripon Society July, 1965 Vol

THE RIPON NEWSLETTER OF . F . THE RIPON SOCIETY JULY, 1965 VOL. 1, No. 5 The View From Here THE GOLDWATER MOVEMENT RESURFACES: A Ripon Editorial Report This month marks the anniv~ of Barry Union, headed by former Congressman Donald Bruce Goldwater's Convention and his nomination to head of Indiana. Many political observers feel that Gold theRePlJblican ticket of 1964. IIi the ~ ~ that has water has made a serious blunder that will only hurt passed, the Goldwater "conservative" crusade has suf- the "conservative" position. We disagree. fered a devastatin£a~=~ setback, as well as the loss The new orGani%lZtlOn, with (F.oldwater's n41IUI, hIlS of its own party' Dean Burch. When Ohio's real prospects Of huilding a powerful memhershie and Ray Bliss was elected to the Republican Party chair resource hlUe. As Senate R.e~ican Lediler Dirksen manship in January, veteran political correspondents slwewiUl ohser1led,in politics "there is no substitute lor who were on hand in Chicago spoke of ..the end of money.' .Goldwlller wants a "consensus orgilllnZll the Goldwater era" in R~lican politics. Today, lion" for conser1lIll!1les and with the resourcel he com this forecast seems to have been premature. For die manils, he Clltl get it. Alread, there are reports thlll the Goldwater Right is very much alive and dominating the PSA will tap some ofthe est,mated $600,000 still heing political news. The moderate Republicans, who nave withheld from the Pari, hI the Citizens Committee fOr learned little from recent party histo9', are as confused GoldWlller-Mill81' and the Nlllional Tele1lision Com";'" and leaderless today as they were before San Franc::isco. -

Introduction to Volume 1 the Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 by Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009

Introduction to volume 1 The Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 By Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009 Biography may or may not be the key to history, but the biographies of those who served in institutions of government can throw great light on the workings of those institutions. These biographies of Australia’s senators are offered not only because they deal with interesting people, but because they inform an assessment of the Senate as an institution. They also provide insights into the history and identity of Australia. This first volume contains the biographies of senators who completed their service in the Senate in the period 1901 to 1929. This cut-off point involves some inconveniences, one being that it excludes senators who served in that period but who completed their service later. One such senator, George Pearce of Western Australia, was prominent and influential in the period covered but continued to be prominent and influential afterwards, and he is conspicuous by his absence from this volume. A cut-off has to be set, however, and the one chosen has considerable countervailing advantages. The period selected includes the formative years of the Senate, with the addition of a period of its operation as a going concern. The historian would readily see it as a rational first era to select. The historian would also see the era selected as falling naturally into three sub-eras, approximately corresponding to the first three decades of the twentieth century. The first of those decades would probably be called by our historian, in search of a neatly summarising title, The Founders’ Senate, 1901–1910. -

Thirteenth Annual Report 2001

ACCESS TO SERVICES Office Holders President: The Honourable Don Wing, MLC Telephone: [03] 6233 2322 Facsimile: [03] 6233 4582 Email: [email protected] Deputy President and Chair of Committees: The Honourable Jim Wilkinson, MLC Telephone: [03] 6233 2980 Facsimile: [03] 6231 1849 Email: [email protected] Executive Officers Clerk of the Council: Mr R.J. Scott McKenzie Telephone: [03] 6233 2331 Email: [email protected] Deputy Clerk: Mr David T. Pearce Telephone: [03] 6233 2333 Email: [email protected] Clerk-Assistant and Usher of the Black Rod Miss Wendy M. Peddle Telephone: [03] 6233 2311 Email: [email protected] Second Clerk-Assistant and Clerk of Committees: Mrs Sue E. McLeod Telephone: [03] 6233 6602 Email: [email protected] Enquiries General: Telephone : [03] 6233 2300/3075 Facsimile: [03] 6231 1849 Papers Office: Telephone : [03] 6233 6963/4979 Parliament’s Website: http://www.parliament.tas.gov.au Legislative Council Report 2001-2002 Page 1 Postal Address: Legislative Council, Parliament House, Hobart, Tas 7000 Legislative Council Report 2001-2002 Page 2 PUBLIC AWARENESS The Chamber During the year a variety of groups and individuals are introduced to the Parliament and in particular the Legislative Council through conducted tours. The majority of the groups conducted through the Parliament during the year consisted of secondary and primary school groups. The majority of groups and other visitors who visited the Parliament did so when the Houses were in session giving them a valuable insight into the debating activity that occurs on the floor of both Houses. -

Bicameralism in the New Zealand Context

377 Bicameralism in the New Zealand context Andrew Stockley* In 1985, the newly elected Labour Government issued a White Paper proposing a Bill of Rights for New Zealand. One of the arguments in favour of the proposal is that New Zealand has only a one chamber Parliament and as a consequence there is less control over the executive than is desirable. The upper house, the Legislative Council, was abolished in 1951 and, despite various enquiries, has never been replaced. In this article, the writer calls for a reappraisal of the need for a second chamber. He argues that a second chamber could be one means among others of limiting the power of government. It is essential that a second chamber be independent, self-confident and sufficiently free of party politics. I. AN INTRODUCTION TO BICAMERALISM In 1950, the New Zealand Parliament, in the manner and form it was then constituted, altered its own composition. The legislative branch of government in New Zealand had hitherto been bicameral in nature, consisting of an upper chamber, the Legislative Council, and a lower chamber, the House of Representatives.*1 Some ninety-eight years after its inception2 however, the New Zealand legislature became unicameral. The Legislative Council Abolition Act 1950, passed by both chambers, did as its name implied, and abolished the Legislative Council as on 1 January 1951. What was perhaps most remarkable about this transformation from bicameral to unicameral government was the almost casual manner in which it occurred. The abolition bill was carried on a voice vote in the House of Representatives; very little excitement or concern was caused among the populace at large; and government as a whole seemed to continue quite normally. -

Imagereal Capture

FEDERAL DEADLOCKS : ORIGIN AND OPERATION OF SECTION 57 By J. E. RICHARDSON* This article deals with the interpretation of section 57 of the Con- stitution, and the consideration of deadlocks leading to the framing of a section at the Federal Convention Debates in Sydney in 1891 and in the three sessions held at Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne respectively in 1897-8. It also includes a short assessment of the operation of section 57 since federation. Section 57 becomes explicable only after the nature of Senate legislative power as defined in section 53 is understood. Accordingly, the article commences by examining Senate legislative power. The two sections read: '53. Proposed laws appropriating revenue or moneys, or imposing taxation, shall not originate in the Senate. But a proposed law shall not be taken to appropriate revenue or moneys, or to impose taxation, by reason only of its containing provisions for the imposition or appropriation of fines or other pecuniary penalties, or for the demand or payment or appropriation of fees for licences, or fees for services under the proposed law. The Senate may not amend proposed laws imposing taxation, or propoaed laws appropriating revenue or moneys for the ordinary annual services of the Government. The Senate may not amend any proposed law so as to increase any pro- posed charge or burden on the people. The Senate may at any stage return to the House of Representatives any proposed law which the Senate may not amend, requesting, by message, the omission or amendment of any items or provisions therein. And the House of Representatives may, if it thinks fit, make any of such omissions or amendments, with or without modifications. -

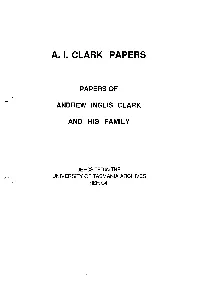

A. I. Clark Papers

A. I. CLARK PAPERS PAPERS OF r-. i - ANDREW INGLIS CLARK AND HIS FAMILY DEPOSITED IN THE UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA ARCHIVES REF:C4 - II 1_ .1 ~ ) ) AI.CLARK INDEXOF NAMES NAME AGE DESCN DATE TOPIC REF Allen,J.H. lelter C4/C9,10 Allen,Mary W. letter C4/C11,12 AspinallL,AH. 1897 Clark's resign.fr.Braddon ministry C4/C390 Barton,Edmund 1849-1920 poltn.judge,GCMG.KC 1898 federation C4/C15 Bayles,J.E. 1885 Index": Tom Paine C4/H6 Berechree c.1905 Berechree v Phoenix Assurance Cc C4/D12 Bird,Bolton Stafford 1840-1924 1885 Brighton ejection C4/C16 Blolto,Luigi of Italy 1873-4 Pacific & USA voyage C4/C17,18 Bowden 1904-6? taxation appeal C4/D10 Braddon,Edward Nicholas Coventry 1829-1904 politn.KCMG 1897 Clark's resign. C4/C390 Brown,Nicholas John MHA Tas. 1887 Clark & Moore C4/C19 Burn,William 1887 Altny Gen.appt. C4/C20 Butler,Charles lawyer 1903 solicitor to Mrs Clark C4/C21 Butler,Gilbert E. 1897 Clark's resign. .C4/C390 Camm,AB 1883 visit to AIClark C4/C22-24 Clark & Simmons lawyers 1887,1909-18 C4/D1-17,K.4,L16 Clark,Alexander Inglis 1879-1931 sAl.C.engineer 1916,21-26 letters C4/L52-58,L Clark,Alexander Russell 1809-1894 engineer 1842-6,58-63 letter book etc. C4/A1-2 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 jUdge 1870-1907 papers C4/C-J Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 judge 1901 Acting Govnr.appt. C4/E9 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848·1907 jUdge 1907-32 estate of C4/K7,L281 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 judge 1958 biog.