Jews in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Storytelling

Volume 34, Number 8 the May 2015 Iyyar/SivanVolume 31, Number 5775 7 March 2012 TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM Adar / Nisan 5772 JEWISH R STORYTELLINGi Pu M DIRECTORY SERVICES SCHEDULE GENERAL INFORMATION: All phone numbers use (510) prefix unless otherwise noted. Services, Location, Time Monday & Thursday Mailing Address 336 Euclid Ave. Oakland, CA 94610 Morning Minyan, Chapel, 8:00 a.m. Hours M-Th: 9 a.m.-4 p.m., Fr: 9 a.m.-3 p.m. Friday Evening Office Phone 832-0936 (Kabbalat Shabbat), Chapel, 6:15 p.m. Office Fax 832-4930 Shabbat Morning, Sanctuary, 9:30 a.m. E-Mail [email protected] Candle Lighting (Friday) Gan Avraham 763-7528 May 1, 7:41 p.m. Bet Sefer 663-1683 May 8, 7:48 p.m. STAFF May 15, 7:54 p.m. May 22, 8:00 p.m. Rabbi (x 213) Mark Bloom Richard Kaplan, May 29, 8:05 p.m. Cantor [email protected] Torah Portions (Saturday) Gabbai Marshall Langfeld May 2, Acharei-Kedoshim Executive Director (x 214) Rayna Arnold May 9, Emor Office Manager (x 210) Virginia Tiger May 16, Behar-Bechukotai Bet Sefer Director Susan Simon 663-1683 May 23, Bamidbar Gan Avraham Director Barbara Kanter 763-7528 May 30, Naso Bookkeeper (x 215) Kevin Blattel Facilities Manager (x 211) Joe Lewis Kindergym/ Dawn Margolin 547-7726 Toddler Program TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM Volunteers (x 229) Herman & Agnes Pencovic OFFICERS OF THE BOARD is proud to support the Conservative Movement by affiliating with The United President Mark Fickes 652-8545 Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. Vice President Eric Friedman 984-2575 Vice President Alice Hale 336-3044 Vice President Flo Raskin 653-7947 Vice President Laura Wildmann 601-9571 Advertising Policy: Anyone may sponsor an issue Secretary JB Leibovitch 653-7133 of The Omer and receive a dedication for their Treasurer Susan Shub 852-2500 business or loved one. -

Russian Restaurant & Vodka Lounge M O SC O W

Moscow on the hill Russian Restaurant & Vodka Lounge Appetizers Russian meals always start with zakuski. Even in the most modest households there is some simple dish, if only a her- ring, to go with a glass of vodka. Zakuski become more elaborate and lavish according of to the wealth of each family. Appetizer Tasting Platter (served with bread basket) 19.95 Chef’s selection of appetizers. Today’s selection is presented on our Specials menu Russian Herring 7.95 Chilled Beet Soup Svekolnick 4.95 Cured herring filet, onion, olives, pickled beets,baby potatoes, Beets broth, lemon juice, chopped cucumber, hardboiled egg, dill, cold-pressed sunflower oil green onion, dill, sour cream Blini with Chicken 7.95 Borscht 4.95 Two crepes stuffed with braised Wild Acres chicken, served Classic Russian beet, cabbage and potato soup garnished with with sour cream sour cream and fresh dill Blini with Caviar 9.95 Piroshki (Beef and Cabbage) 7.95 Salmon roe rolled in crepe with dill, scallions, sour cream Two filled pastries, dill-sour cream sauce Duck “Faux” Gras Pate 5.95 Assorted Pickled Vegetables 4.95 Wild Acres farm duck liver pate, fruit chutney, toasts Seasonal variety of house pickled vegetables Lamb Cheboureki 7.95 Russian Garden Salad 6.95 Ground lamb-stuffed pastries puffed in hot oil, Tomato, cucumber, bell pepper, sweet onion, lettuce tossed with served with tomato-garlic relish cold-pressed sunflower oil vinaigrette, green onion & fresh dill Escargot 9.95 Side Salad 5.95 White wine garlic butter sauce and sprinkled with cheese Mixed greens, -

Watermark University

202Spring S1emester JANUARY THROUGH APRIL Hello and thank you for your interest in Watermark University - Spring Semester! The foundation of Watermark University (WU) is to provide meaningful opportunities to learn, teach and grow, resulting in a life of overall well-being. At The Watermark Brooklyn Heights, we pride ourselves in finding thought leaders throughout New York City and beyond to teach informative courses about a wide range of interesting and cutting edge topics. Research shows that learning and keeping our mind active and sharp supports healthy aging. At Watermark Retirement Communities® we are committed to encouraging our residents and associates to lead balanced lives, full of meaning and purpose, grounded in self-awareness and infused with curiosity. Our Watermark University courses help achieve this goal by inspiring us to go beyond our daily lives in finding ways we can truly thrive in our communities. By focusing on the Seven Dimensions of Well-being: Physical, Social, Intellectual, Spiritual, Emotional, Environmental, and Vocational we offer the opportunity to achieve a balanced life and we see the benefits across the country in every class, every day. Sincerely, Aaron Feinstein Aaron Feinstein Director of People, Arts and Culture COURSES FACULTY DAY AND TIME LOCATION Inside the World of Tuesday, January 19 • American Sign Language Sahar Edalati Performing Arts Center 4:00 PM (ASL) and Music Come and learn a new way to experience MUSIC through signs! In this beginner ASL course, participants will learn how to convey rhythm and emotions for a variety of musical genres. We will practice showing when the bass drops, soaring pop rock ballads, and a little bit of hip hop to name just a few. -

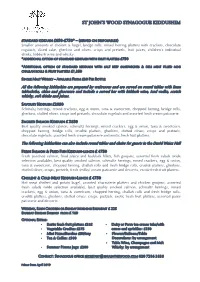

St John's Wood Synagogue Kiddushim

ST JOHN’S WOOD SYNAGOGUE KIDDUSHIM STANDARD KIDDUSH £650-£750* – (SERVED ON DISPOSABLES) Smaller amounts of cholent & kugel, bridge rolls, mixed herring platters with crackers, chocolate rogalach, sliced cake, gherkins and olives, crisps and pretzels, fruit juices, children’s individual drinks, kiddush wine and whisky. *ADDITIONAL OPTION OF STANDARD KIDDUSH WITH FRUIT PLATTERS £750 *ADDITIONAL OPTION OF STANDARD KIDDUSH WITH SALT BEEF SANDWICHES & DELI MEAT FILLED MINI CHALLAH ROLLS & FRUIT PLATTERS £1,350 SINGLE MALT WHISKY – AVAILABLE FROM £30 PER BOTTLE All the following kiddushim are prepared by waitresses and are served on round tables with linen tablecloths, china and glassware and include a served bar with kiddush wine, iced vodka, scotch whisky, soft drinks and juices. SAVOURY KIDDUSH £2050 Schmaltz herrings, mixed crackers, egg & onion, tuna & sweetcorn, chopped herring, bridge rolls, gherkins, stuffed olives, crisps and pretzels, chocolate rogelach and assorted fresh cream patisserie. SMOKED SALMON KIDDUSH £ 2850 Best quality smoked salmon, schmaltz herrings, mixed crackers, egg & onion, tuna & sweetcorn, chopped herring, bridge rolls, crudité platters, gherkins, stuffed olives, crisps and pretzels, chocolate rogelach, assorted fresh cream patisserie and exotic fresh fruit platters. The following kiddushim can also include round tables and chairs for guests in the David Weisz Hall FRESH SALMON & FRIED FISH KIDDUSH-LUNCH £ 4750 Fresh poached salmon, fried plaice and haddock fillets, fish goujons, assorted fresh salads (wide selection available), best quality smoked salmon, schmaltz herrings, mixed crackers, egg & onion, tuna & sweetcorn, chopped herring, challah rolls and fresh bridge rolls, crudité platters, gherkins, stuffed olives, crisps, pretzels, fresh (milky) cream patisserie and desserts, exotic fresh fruit platters. -

Leket-Israel-Passove

Leave No Crumb Behind: Leket Israel’s Cookbook for Passover & More Passover Recipes from Leket Israel Serving as the country’s National Food Bank and largest food rescue network, Leket Israel works to alleviate the problem of nutritional insecurity among Israel’s poor. With the help of over 47,000 annual volunteers, Leket Israel rescues and delivers more than 2.2 million hot meals and 30.8 million pounds of fresh produce and perishable goods to underprivileged children, families and the elderly. This nutritious and healthy food, that would have otherwise gone to waste, is redistributed to Leket’s 200 nonprofit partner organizations caring for the needy, reaching 175,000+ people each week. In order to raise awareness about food waste in Israel and Leket Israel’s solution of food rescue, we have compiled this cookbook with the help of leading food experts and chefs from Israel, the UK , North America and Australia. This book is our gift to you in appreciation for your support throughout the year. It is thanks to your generosity that Leket Israel is able to continue to rescue surplus fresh nutritious food to distribute to Israelis who need it most. Would you like to learn more about the problem of food waste? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter or visit our website (www.leket.org/en). Together, we will raise awareness, continue to rescue nutritious food, and make this Passover a better one for thousands of Israeli families. Happy Holiday and as we say in Israel – Beteavon! Table of Contents Starters 4 Apple Beet Charoset 5 Mina -

5778 Haroset Customs and Ingredients: No Matter How You Spell It Haroset Haroset Charoset Charoseth Kharoset Haroseth

© 2018 Foundation For Family Education, Inc. / TKS Rabbi Barry Dov Lerner, President 5778 Haroset Customs and Ingredients: No Matter How You Spell It haroset haroset charoset charoseth kharoset haroseth haroses charoses A Hands-On Workshop Experience In the Tastes, Sights, Smells of the Passover Holiday Led By Rabbi Barry Dov Lerner © 2018 Foundation For Family Education, Inc. / TKS Rabbi Barry Dov Lerner, President 1 © 2018 Foundation For Family Education, Inc. / TKS Rabbi Barry Dov Lerner, President 5778 Haroset Customs and Ingredients: No Matter How You Spell It haroset haroset charoset charoseth kharoset haroseth . Family Participation Is The Essential Ingredient In All Passover Recipes There was always a sense of warmth and support when we sat in the kitchen, whether we were watching Mom (in those days it was generally a Mom thing) prepare some new or familiar dish, or when we were invited to actually participate in the cooking or baking. Not only did we have a chance to be drawn in to the actual task, but we had an extended and supportive opportunity to talk about whatever was on either her mind or on ours. Somehow it was the most encouraging environment for what today we call “communication.” The informality linked with the tastes and smells and the sight of the cooking and baking seemed just right. Today, one of the phenomena of the modern modern American family is that fathers are cooking and baking more than ever before; some claim that it is quickly becoming the number one avocation of men between the ages of 25 and 45. -

Challah French Toast Buttermilk Pancakes Waffles

ROAST CHICKEN ................................................................HALF 14 / WHOLE 26 20 DEVILED EGGS ...........................................................................................3 challah, apple, onion & sage with gravy for two hours paprika, shallot crackling SPICY HONEY FRIED CHICKEN ...................................................................16 LATKES sesame seeds & coriander sour cream & apple sauce ................................................................................5 SALMON FILLET .......................................................................................................17 ..............................................................7 PASTRAMI & CHEESE FRIES shaved fennel, marcona almonds & green olives STEAK FRITES �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������25 9oz rib-eye with bearnaise (add egg 1) BUTTERMILK PANCAKES AVOCADO BAGEL ......................................................................................7 crushed avocado with chili & lemon, red onion, radishes & blueberry compote.............................................8 CAESAR ....................................................................................................... 9 buttermilk dressing on poppy bagel baby gem, grana, challah croutons & anchovies (add chicken 4) maple, butter & bacon.......................................9 BODEGA CLASSIC .....................................................................................................8 bacon, -

A Taste of Teaneck

.."' Ill • Ill INTRODUCTION In honor of our centennial year by Dorothy Belle Pollack A cookbook is presented here We offer you this recipe book Pl Whether or not you know how to cook Well, here we are, with recipes! Some are simple some are not Have fun; enjoy! We aim to please. Some are cold and some are hot If you love to eat or want to diet We've gathered for you many a dish, The least you can do, my dears, is try it. - From meats and veggies to salads and fish. Lillian D. Krugman - And you will find a true variety; - So cook and eat unto satiety! - - - Printed in U.S.A. by flarecorp. 2884 nostrand avenue • brooklyn, new york 11229 (718) 258-8860 Fax (718) 252-5568 • • SUBSTITUTIONS AND EQUIVALENTS When A Recipe Calls For You Will Need 2 Tbsps. fat 1 oz. 1 cup fat 112 lb. - 2 cups fat 1 lb. 2 cups or 4 sticks butter 1 lb. 2 cups cottage cheese 1 lb. 2 cups whipped cream 1 cup heavy sweet cream 3 cups whipped cream 1 cup evaporated milk - 4 cups shredded American Cheese 1 lb. Table 1 cup crumbled Blue cheese V4 lb. 1 cup egg whites 8-10 whites of 1 cup egg yolks 12-14 yolks - 2 cups sugar 1 lb. Contents 21/2 cups packed brown sugar 1 lb. 3112" cups powdered sugar 1 lb. 4 cups sifted-all purpose flour 1 lb. 4112 cups sifted cake flour 1 lb. - Appetizers ..... .... 1 3% cups unsifted whole wheat flour 1 lb. -

Pdf (Accessed on 1 February 2018)

molecules Article Physicochemical, Functional, and Nutraceutical Properties of Eggplant Flours Obtained by Different Drying Methods Jenny R. Rodriguez-Jimenez 1 , Carlos A. Amaya-Guerra 1,* , Juan G. Baez-Gonzalez 1 , Carlos Aguilera-Gonzalez 1 , Vania Urias-Orona 2 and Guillermo Nino-Medina 3,* 1 Facultad de Ciencias Biologicas, Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Ave. Universidad S/N, Cd. Universitaria, 66450 San Nicolas de los Garza, Mexico; [email protected] (J.R.R.-J.); [email protected] (J.G.B.-G.); [email protected] (C.A.-G.) 2 Laboratorio de Quimica y de Alimentos, Facultad de Salud Publica y Nutricion, Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Col. Mitras Centro, C.P. 64460 Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Laboratorio de Quimica y Bioquimica, Facultad de Agronomia, Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Francisco Villa S/N, Col. Ex-Hacienda El Canada, C.P. 66050 General Escobedo, Nuevo Leon, Mexico * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.A.A.-G.); [email protected] (G.N.-M.) Academic Editors: Alessandra Durazzo and Massimo Lucarini Received: 29 October 2018; Accepted: 2 December 2018; Published: 5 December 2018 Abstract: The importance of consuming functional foods has led the food industry to look for alternative sources of ingredients of natural origin. Eggplants are a type of vegetable that is valued for its content in phytochemical compounds and it is due to the fact that this research is conducted towards the development of eggplant flour as a proposal to be used as a functional ingredient in the food industry. In this study, the eggplant fruits were divided into four groups, based on the drying method and the equipment used: Minced, drying oven (T1); sliced, drying oven (T2); sliced and frozen, drying tunnel (T3); and sliced, drying tunnel (T4). -

Instruction Mannual Part

1map? fl r,fl 6 ietary Interviewer’s Manual for %e Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examirkion Survey, 1982434 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES * Public Health Service * National Center for Health Statistics .------I ;:.:.:.:.:. ::.:::::::. :::::. ..I .:.,....‘.‘.~.‘.~.~.~.~.‘. -c b .‘.‘.‘.‘.~.‘.‘.’ .‘,‘.‘,‘,‘,~,‘.‘_‘,’ .~.‘.‘.~.‘.‘.~.‘.~.‘.’ This manual was prepared by V\!estat with assistance from Development Associates. Part 15f ● Dieta~ Interviewer’s Manual for the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1982-84 HHANES Data Collection U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsviller Maryland August 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I. GENERAL INTERVIEWING TECHNIQUES Chapter Page 1 OVERVIEW OF THE HISPANIC HANES ..................................... 1-1 1.1 Introduction ..........● ......,.............................. 1-1 1.2 History of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Program .................,......................... 1-1 1.3 Purpose of the Hispanic HANES .........0....0................ 1-2 1.4 Method of Data Collection ................................... 1-3 1.5 Confidentiality ...,............● ...................● ...0 ● .● . 1-6 1.6 Informed Consent ............................................ 1-6 1.7 Professional Ethics ......................................... 1-7 2 BEFORE BEGINNINGTHE INTERVIEW ..................................... 2-1 2.1 Review Your Interviewer’s Manual and Other Study Materials.. 2-1 2.2 Review the Questionnaire -

Chapter 1 Definitions and Classifications for Fruit and Vegetables

Chapter 1 Definitions and classifications for fruit and vegetables In the broadest sense, the botani- Botanical and culinary cal term vegetable refers to any plant, definitions edible or not, including trees, bushes, vines and vascular plants, and Botanical definitions distinguishes plant material from ani- Broadly, the botanical term fruit refers mal material and from inorganic to the mature ovary of a plant, matter. There are two slightly different including its seeds, covering and botanical definitions for the term any closely connected tissue, without vegetable as it relates to food. any consideration of whether these According to one, a vegetable is a are edible. As related to food, the plant cultivated for its edible part(s); IT botanical term fruit refers to the edible M according to the other, a vegetable is part of a plant that consists of the the edible part(s) of a plant, such as seeds and surrounding tissues. This the stems and stalk (celery), root includes fleshy fruits (such as blue- (carrot), tuber (potato), bulb (onion), berries, cantaloupe, poach, pumpkin, leaves (spinach, lettuce), flower (globe tomato) and dry fruits, where the artichoke), fruit (apple, cucumber, ripened ovary wall becomes papery, pumpkin, strawberries, tomato) or leathery, or woody as with cereal seeds (beans, peas). The latter grains, pulses (mature beans and definition includes fruits as a subset of peas) and nuts. vegetables. Definition of fruit and vegetables applicable in epidemiological studies, Fruit and vegetables Edible plant foods excluding -

Complete Passover Dinners

complete passover dinners dinner for 6 | $269 Gefilte Fish(6 pcs.) with Red Horseradish (1 Lb.) Chicken Soup (3 Qts.) with Matzoh Balls (8) pass Brisket Pot Roast (4 Lbs.) with Gravy (1 Qt.) pass Homemade Potato Latkes (2 Lbs.) with Homemade Apple Sauce (1 Lb.) One Vegetable Soufflé Israeli Matzoh (1 Box) over Macaroons (1 Container) and Honey Cake (1) dinner for 12 | $479 Gefilte Fish(12 pcs.) with Red Horseradish (2 Lbs.) 2019 Chicken Soup (6 Qts.) with Matzoh Balls (16) Brisket Pot Roast (7 Lbs.) with Gravy (2 Qts.) Homemade Potato Latkes (3 Lbs.) with Homemade Apple Sauce (2 Lbs.) Two Vegetable Soufflé Israeli Matzoh (2 Boxes) Macaroons (2 Containers) and Honey Cake (2) seder plates Complete Seder Plate $29.99 with Haroset, Parsley, Egg, Shank Bone and Horseradish ZABARS.COM Seder Plate $19.99 Passover Ingredients Kit $9.99 great beginnings Chopped Chicken Liver 8 oz. | $4.99 Homemade Gefilte Fish* 4 pcs. | $6.50 12 pcs. | $19.50 24 pcs. | $39 in course *Two pieces per serving. ma s European Sweet Gefilte Fish 1 Lb. | $11.99 2 Lb. | $23.90 3 Lb. | $35.85 Brisket Pot Roast Homestyle Red Horseradish 8 oz. | $2.99 16 oz. | $5.99 Whole First Cut – Min. Wt. 6 lb. | $155.00 • 1 lb. Sliced | $27.49 Gold’s White Horseradish (Kosher for Passover) 8 oz. | $2.99 Gravy – Qt. | $10.49 Zabar’s Original Haroset $9.49/Lb. Brisket Tzimmes Zabar’s Nova (Pre-packaged and sliced) 1 Lb. | $29.98 ½ Lb. | $17.98 1 Lb | $19.49 Zabar’s Handsliced Nova or Scotch Cured Salmon 1 Lb.