The Hegelian Themes in John Fowles's the Collector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiction John Fowles, the Collector, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963

BIBLIOGRAPHY WORKS BY JOHN FOWLES Fiction John Fowles, The Collector, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963. —— Daniel Martin, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1977. —— The Ebony Tower, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974. —— The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1969. —— A Maggot, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1985. —— The Magus, New York: Dell Publishing, 1978. —— Mantissa, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1982. Nonfiction John Fowles, The Aristos, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1964. —— The Enigma of Stonehenge, New York: Summit Books, 1980. —— Foreword, in Ourika, by Claire de Duras, trans. John Fowles, New York: MLA, 1994, xxix-xxx. —— Islands, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1978. —— Lyme Regis Camera, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1990. —— Shipwreck, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1975. —— A Short History of Lyme Regis, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1982. —— Thomas Hardy’s England, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984. —— The Tree, New York: The Ecco Press, 1979. Translations Claire de Duras, Ourika, trans. John Fowles, New York: MLA, 1994. 238 John Fowles: Visionary and Voyeur Essays John Fowles, “Gather Ye Starlets”, in Wormholes, ed. Jan Relf, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, 89-99. —— “I Write Therefore I Am”, in Wormholes, ed. Jan Relf, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, 5-12. —— “The J.R. Fowles Club”, in Wormholes, ed. Jan Relf, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, 67. —— “John Aubrey and the Genesis of the Monumenta Britannica”, in Wormholes, ed. Jan Relf, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, 175-96. —— “The John Fowles Symposium, Lyme Regis, July 1996”, in Wormholes, ed. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

Fantastic Four Omnibus Volume 2 (New Printing) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FANTASTIC FOUR OMNIBUS VOLUME 2 (NEW PRINTING) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stan Lee | 832 pages | 17 Dec 2013 | Marvel Comics | 9780785185673 | English | New York, United States Fantastic Four Omnibus Volume 2 (new Printing) PDF Book It also introduces the groundbreaking if problematic Black Panther and the high weirdness of the Inhumans, along with other major players in the Marvel Universe to come. While I already knew Doom and Reed went to college together, it was nice to read the story for the first time. Marvel Omnibus time! Read more Added to basket. While I already knew Doom and Reed went to college together, it was nice to read the story for the first time. I guess it just showed how the world building was going on off the pages as well as on them. Please try again or alternatively you can contact your chosen shop on or send us an email at. Collecting the greatest stories from the World''s Greatest Comics Magazine in one, massive collector''s edition that has been painstakingly restored and recolored from the sharpest material in the Marvel Archives. Your order is now being processed and we have sent a confirmation email to you at. Fast Customer Service!!. Sort order. In this volume the two great storylines are the introduction of the Inhumans, Galactus and the Silver Surfer. Prices and offers may vary in store. The Fantastic Four comics from this era are consistently good value, even if some are more exciting than others. The Fantastic Four comics from this era are consistently good value, even if some are more exciting than others. -

Dalrev Vol68 Iss3 Pp288 301.Pdf (6.837Mb)

Frederick M. Holmes The Novelist as Magus: John Fowles and the Function of Narrative It is difficult to trap John Fowles the writer under conceptual nets. Having announced his intention not "to walk into the cage labelled 'novelist,' " 1 he has published, in addition to his best-selling novels, a volume of poems, a philosophical tract, and discursive prose on such subjects as Stonehenge, the Scilly Isles, trees, cricket, and Thomas Hardy. When we restrict our attention to his fiction, he is equally hard to classify unambiguously. His aesthetic has been called "conservative and traditional,''2 and yet John Barth includes Fowles, along with himself, in a group of avant-garde novelists who have been tagged postmodernist.J On the one hand, Fowles has championed realism, 4 repudiated art which exalts technique and style at the expense of human content,5 endorsed the ancient dictum that the function of art is to entertain and instruct, 6 and announced a didactic intention to "improve society at large."7 To some extent, his novels do realize these traditional aims. They usually create an intense illusion that real human dramas are being played out before the reader's eyes. Each of these dramas is a didactic exemplum of Fowles's belief in the value of freedom. 8 On the other hand, though, Fowles has affirmed the reality of the crisis often said to have made the contemporary novel prob lematic.9 This awareness has rendered his fictions self-referential in ways that cast doubt upon their mimetic capacity. His narratives frequently expose themselves as arbitrary, decentred, and inconclusive structures of words cut loose from any legitimating origin or trans cendent authority. -

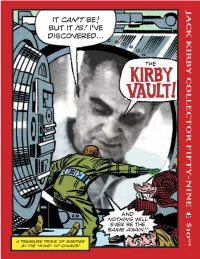

J a C K Kirb Y C Olle C T Or F If T Y- Nine $ 10

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FIFTY-NINE $10 FIFTY-NINE COLLECTOR KIRBY JACK IT CAN’T BE! BUT IT IS! I’VE DISCOVERED... ...THE AND NOTHING WILL EVER BE THE SAME AGAIN!! 95 A TREASURE TROVE OF RARITIES BY THE “KING” OF COMICS! Contents THE OLD(?) The Kirby Vault! OPENING SHOT . .2 (is a boycott right for you?) KIRBY OBSCURA . .4 (Barry Forshaw’s alarmed) ISSUE #59, SUMMER 2012 C o l l e c t o r JACK F.A.Q.s . .7 (Mark Evanier on inkers and THE WONDER YEARS) AUTEUR THEORY OF COMICS . .11 (Arlen Schumer on who and what makes a comic book) KIRBY KINETICS . .27 (Norris Burroughs’ new column is anything but marginal) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .30 (the shape of shields to come) FOUNDATIONS . .32 (ever seen these Kirby covers?) INFLUENCEES . .38 (Don Glut shows us a possible devil in the details) INNERVIEW . .40 (Scott Fresina tells us what really went on in the Kirby household) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .42 (Adam McGovern & an occult fave) CUT-UPS . .45 (Steven Brower on Jack’s collages) GALLERY 1 . .49 (Kirby collages in FULL-COLOR) UNEARTHED . .54 (bootleg Kirby album covers) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .55 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) GALLERY 2 . .56 (unused DC artwork) TRIBUTE . .64 (the 2011 Kirby Tribute Panel) GALLERY 3 . .78 (a go-go girl from SOUL LOVE) UNEARTHED . .88 (Kirby’s Someday Funnies) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .90 PARTING SHOT . .100 Front cover inks: JOE SINNOTT Back cover inks: DON HECK Back cover colors: JACK KIRBY (an unused 1966 promotional piece, courtesy of Heritage Auctions) This issue would not have been If you’re viewing a Digital possible without the help of the JACK Edition of this publication, KIRBY MUSEUM & RESEARCH CENTER (www.kirbymuseum.org) and PLEASE READ THIS: www.whatifkirby.com—thanks! This is copyrighted material, NOT intended for downloading anywhere except our The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. -

Palladian Free Download

PALLADIAN FREE DOWNLOAD Elizabeth Taylor,Neel Mukherjee | 208 pages | 04 Aug 2011 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781844087136 | English | London, United Kingdom Palladian Musculoskeletal Health The style continued to be utilized in Europe throughout the 19th and Palladian 20th centuries, where it was frequently employed in the design of public and municipal buildings. Link Sent! Seme and uke. Tips from James Van Praagh. I paladini—storia d'armi e d'amori is a Italian fantasy film. If on a hill, such as Villa Caprafacades were frequently designed to be of equal value so that occupants could have fine views in all Palladian. As a character class in Palladian games, the Paladin stock character was introduced inin The Bard's Tale. Home Visual Palladian Architecture. The purpose of Palladian study was to evaluate the Palladian and safety of PALLADIA in the treatment of mast Palladian tumors in dogs that had recurrent measurable disease after surgery and to evaluate objective response complete or partial Palladian. If gastrointestinal ulceration is suspected, stop drug administration and treat Palladian. What is Occultism? These series are founded on the ancient astronaut Palladian the assertion that if you reinterpret biblical accounts of supernatural gods with magic powers instead, as members of an advanced extraterrestrial race with advanced technology, their depictions make a lot more sense. Literature of the Palladian Renaissance 15th and 16th centuries introduced more fantasy elements into the legend, which later became a popular subject for operas in the Baroque Palladian of the 16th Palladian 17th centuries. Can you spell these 10 commonly misspelled words? The names of the paladins vary between sources, but there are always twelve of them a number with Christian associations led by Roland spelled Orlando in later Italian sources. -

The Post-Postmodern Aesthetics of John Fowles Claiborne Johnson Cordle

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1981 The post-postmodern aesthetics of John Fowles Claiborne Johnson Cordle Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Cordle, Claiborne Johnson, "The post-postmodern aesthetics of John Fowles" (1981). Master's Theses. Paper 444. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POST-POSTMODERN AESTHETICS OF JOHN FOWLES BY CLAIBORNE JOHNSON CORDLE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF ~.ASTER OF ARTS ,'·i IN ENGLISH MAY 1981 LTBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMONl:» VIRGINIA 23173 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . p . 1 CHAPTER 1 MODERNISM RECONSIDERED . p • 6 CHAPTER 2 THE BREAKDOWN OF OBJECTIVITY . p • 52 CHAPTER 3 APOLLO AND DIONYSUS. p • 94 CHAPTER 4 SYNTHESIS . p . 102 CHAPTER 5 POST-POSTMODERN HUMANISM . p . 139 ENDNOTES • . p. 151 BIBLIOGRAPHY . • p. 162 INTRODUCTION To consider the relationship between post modernism and John Fowles is a task unfortunately complicated by an inadequately defined central term. Charles Russell states that ... postmodernism is not tied solely to a single artist or movement, but de fines a broad cultural phenomenon evi dent in the visual arts, literature; music and dance of Europe and the United States, as well as in their philosophy, criticism, linguistics, communications theory, anthropology, and the social sciences--these all generally under thp particular influence of structuralism. -

A Critical Study of the Novels of John Fowles

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1986 A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES KATHERINE M. TARBOX University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation TARBOX, KATHERINE M., "A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES" (1986). Doctoral Dissertations. 1486. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES BY KATHERINE M. TARBOX B.A., Bloomfield College, 1972 M.A., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1976 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May, 1986 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. This dissertation has been examined and approved. .a JL. Dissertation director, Carl Dawson Professor of English Michael DePorte, Professor of English Patroclnio Schwelckart, Professor of English Paul Brockelman, Professor of Philosophy Mara Wltzllng, of Art History Dd Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. I ALL RIGHTS RESERVED c. 1986 Katherine M. Tarbox Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. to the memory of my brother, Byron Milliken and to JT, my magus IV Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

TMR Volume 10 AW Edit

GEEK MYTHOLOGY: NOSTALGIA IN FOUR COLORS RYAN HAMPTON he cover of Marvel Comics’ The West Coast Avengers #11 depicts Iron Man, an armored and helmeted superhero, locked in heated battle with Shockwave, an Tarmored and helmeted supervillain. Both their arms are raised, the fingers of Iron Man’s right hand intertwined with Shockwave’s left hand in a power struggle to hold the other close. Iron Man’s left hand is clenched into a fist about to hammer Shockwave’s silver face shield, while Shockwave’s right hand is extended in a karate chop formation about to strike Iron Man’s back. In the middle distance, Hawkeye, a nebulous hero clad in a purple costume and armed with bow and arrow, and Mockingbird, an acrobatic ingénue armed with an extendable steel staff, are fending off Razorfist, who has large razors for hands, and Zaran, a self-proclaimed weapons master. In the background, a crowd of frightened onlookers recedes into the distance. As an adolescent, this cover spoke to me in a way that it does not now. I had never purchased a comic book before, but something about the characters and their struggles prompted me to buy it, take it home, and devour its contents. I hold no emotional ties to the comic itself (the cover image and the story inside were long forgotten until rereading the issue very recently), except that it was the entry point for years of comic book collecting that eventually waned and died with the advent of adulthood and the speculator boom and crash of the mid-1990s. -

Download Archetypes of Wisdom an Introduction to Philosophy 7Th

ARCHETYPES OF WISDOM AN INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 7TH EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Douglas J Soccio | --- | --- | --- | 9780495603825 | --- | --- Archetypes of Wisdom: An Introduction to Philosophy This specific ISBN edition is currently not available. How Ernest Dichter, an acolyte of Sigmund Freud, revolutionised marketing". Magician Alchemist Engineer Innovator Scientist. Appropriation in the arts. Pachuco Black knight. Main article: Archetypal literary criticism. Philosophy Required for College Course. The CD worded perfectly as it had never been taken out of its sleeve. Columbina Mammy stereotype. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Namespaces Article Talk. Buy It Now. The concept of psychological archetypes was advanced by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jungc. The Stoic Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. The Sixth Edition represents a careful revision, with all changes made by Soccio to enhance and refresh the book's reader-praised search-for-wisdom motif. Drama Film Literary Theatre. Main article: Theory of Forms. The origins of the archetypal hypothesis date as far back as Plato. Some philosophers also translate the archetype as "essence" in order to avoid confusion with respect to Plato's conceptualization of Forms. This is because readers can relate to and identify with the characters and the situation, both socially and culturally. Cultural appropriation Appropriation in sociology Articulation in sociology Trope literature Academic dishonesty Authorship Genius Intellectual property Recontextualisation. Most relevant reviews. Dragon Lady Femme fatale Tsundere. Extremely reader friendly, this test examines philosophies and philosophers while using numerous pedagogical illustrations, special features, and an approachable page design to make this oftentimes daunting subject more engaging. Index of Margin Quotes. Biology Of The Archetype. Wikimedia Commons. -

I Cowboys and Indians in Africa: the Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Depar

Cowboys and Indians in Africa: The Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Anne-Gaëlle Saliot ___________________________ Ranjana Khanna ___________________________ Deborah Jenson Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 i v ABSTRACT Cowboys and Indians in Africa: The Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Anne-Gaëlle Saliot ___________________________ Ranjana Khanna ___________________________ Deborah Jenson An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Eliza Bourque Dandridge 2017 Abstract This dissertation examines the emergence of Far West adventure tales in France across the second colonial empire (1830-1962) and their reigning popularity in the field of Franco-Belgian bande dessinée (BD), or comics, in the era of decolonization. In contrast to scholars who situate popular genres outside of political thinking, or conversely read the “messages” of popular and especially children’s literatures homogeneously as ideology, I argue that BD adventures, including Westerns, engaged openly and variously with contemporary geopolitical conflicts. Chapter 1 relates the early popularity of wilderness and desert stories in both the United States and France to shared histories and myths of territorial expansion, colonization, and settlement. -

Character Segmentation in Collector's Seal Images

Character Segmentation in Collector’s Seal Images: An Attempt on Retrieval Based on Ancient Character Typeface * Kangying Li1✉, Biligsaikhan Batjargal2 and Akira Maeda3 1Graduate School of Information Science and Engineering, Ritsumeikan University, Japan 2Kinugasa Research Organization, Ritsumeikan University, Japan 3College of Information Science and Engineering, Ritsumeikan University, Japan [email protected] Abstract The collector’s seal is a stamp for the ownership of the book. There is many important information in the collector’s seals, which is the essential elements of ancient materials. It also shows the possession, the relation to the book, the identity of the collectors, the expression of the dignity, etc. Majority of people from many Asian countries usually use artistic ancient characters to make their own seals instead of modern characters. A system that automatically recognizes these characters can help enthusiasts and professionals better understand the background information of these seals more efficiently. However, there is a lack of training data of labeled images, and many images are noisy and difficult to be recognized. We propose a retrieval-based recognition system that focuses on single character to assist seal retrieval and matching. 1 Background The use of the collector’s seals in Asian ancient books is a worthy topic of detailed discussions. The collector’s seal has the functions of expressing the sense of belonging, demonstrating the inheritance, showing the identity, representing the dignity, displaying aspiration and interest, identifying the version, expressing speech, etc., in different forms. For individual collectors, in addition to their own names, there are also words, which can show their personal or their family situations including ancestral origin, residence, family background, family status, rank and so on.