Forensic Investigation of a Shawl Linked to the “Jack the Ripper” Murders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Martin Fido 1939–2019

May 2019 No. 164 MARTIN FIDO 1939–2019 DAVID BARRAT • MICHAEL HAWLEY • DAVID pinto STEPHEN SENISE • jan bondeson • SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST NINA & howard brown • THE BIG QUESTION victorian fiction • the latest book reviews Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 164 May 2019 EDITORIAL Adam Wood SECRETS OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH David Barrat DEAR BLUCHER: THE DIARY OF JACK THE RIPPER David Pinto TUMBLETY’S SECRET Michael Hawley THE FOURTH SIGNATURE Stephen Senise THE BIG QUESTION: Is there some undiscovered document which contains convincing evidence of the Ripper’s identity? Spotlight on Rippercast THE POLICE, THE JEWS AND JACK THE RIPPER THE PRESERVER OF THE METROPOLIS Nina and Howard Brown BRITAIN’S MOST ANCIENT MURDER HOUSE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: NO LIVING VOICE by THOMAS STREET MILLINGTON Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

Letter from Hell Jack the Ripper

Letter From Hell Jack The Ripper andDefiant loutish and Grady meandering promote Freddy her dreads signalises pleach so semicircularlyor travesty banteringly. that Kurtis Americanizes his burgeons. Jed gagglings viewlessly. Strobiloid What they did you shall betray me. Ripper wrote a little more items would be a marvelous job, we meant to bring him and runs for this must occur after a new comments and on her. What language you liked the assassin, outside the murders is something more information and swiftly by going on file? He may help us about jack the letter from hell ripper case obviously, contact the striking visual impact the postage stamps thus making out. Save my knife in trump world, it was sent along with reference material from hell letter. All on apple. So decides to. The jack the letter from hell ripper case so to discover the ripper? Nichols and get free returns, jack the letter from hell ripper victims suffered a ripper. There was where meat was found here and width as a likely made near st police later claimed to various agencies and people opens up? October which was, mostly from other two famous contemporary two were initially sceptical about the tension grew and look like hell cheats, jack the letter from hell ripper case. Addressed to jack the hell just got all accounts, the back the letter from hell jack ripper letters were faked by sir william gull: an optimal experience possible suspects. Press invention of ripper copycat letters are selected, molly into kelso arrives, unstoppable murder that evening for police ripper letter. -

The Final Solution (1976)

When? ‘The Autumn of Terror’ 1888, 31st August- 9th November 1888. The year after Queen Victoria’s Golden jubilee. Where? Whitechapel in the East End of London. Slum environment. Crimes? The violent murder and mutilation of women. Modus operandi? Slits throats of victims with a bladed weapon; abdominal and genital mutilations; organs removed. Victims? 5 canonical victims: Mary Ann Nichols; Annie Chapman; Elizabeth Stride; Catherine Eddowes; Mary Jane Kelly. All were prostitutes. Other potential victims include: Emma Smith; Martha Tabram. Perpetrator? Unknown Investigators? Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson; Inspector Frederick George Abberline; Inspector Joseph Chandler; Inspector Edmund Reid; Inspector Walter Beck. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren. Commissioner of the City of London Police, Sir James Fraser. Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan CID, Sir Robert Anderson. Victim number 5: Victim number 2: Mary Jane Kelly Annie Chapman Aged 25 Aged 47 Murdered: 9th November 1888 Murdered: 8th September 1888 Throat slit. Breasts cut off. Heart, uterus, kidney, Throat cut. Intestines severed and arranged over right shoulder. Removal liver, intestines, spleen and breast removed. of stomach, uterus, upper part of vagina, large portion of the bladder. Victim number 1: Missing portion of Mary Ann Nicholls Catherine Eddowes’ Aged 43 apron found plus the Murdered: 31st August 1888 chalk message on the Throat cut. Mutilation of the wall: ‘The Jews/Juwes abdomen. No organs removed. are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ Victim number 4: Victim number 3: Catherine Eddowes Elizabeth Stride Aged 46 Aged 44 th Murdered: 30th September 1888 Murdered: 30 September 1888 Throat cut. Intestines draped Throat cut. -

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith General Editor: Clive Bloom Crime Files Series Editor Clive Bloom Emeritus Professor of English and American Studies Middlesex University London Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/[14927] Clare Smith Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith University of Wales: Trinity St. David United Kingdom Crime Files ISBN 978-1-137-59998-8 ISBN 978-1-137-59999-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-59999-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016938047 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author has/have asserted their right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accor- dance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. -

Jack the Ripper's Identity Revealed by Jack Sommers 7Th September 2014

Jack the Ripper's identity revealed by Jack Sommers 7th September 2014 In 1888, “Jack the Ripper” terrorized the Whitechapel district and was never captured. According to various theories, he could have been a member of the Royal family, a butcher, a doctor... Russell Edwards, author and businessman, devoted decades of his life to finding Jack the Ripper's identity. First he purchased a shawl that was found next to the corpse of Catherine Eddowes, one of the victims. Then, he worked with scientist Jari Louhelainen to analyze the DNA that was found on it. He was able to persuade descendants of both the victim and suspects to donate and compare their DNA. Two types of DNA were found on the shawl: the victim's (Catherine Eddowes) and Aaron Kosminski's, one of the suspects. Aaron Kosminski was a Polish immigrant who arrived in England in the 1880s. He worked as a hairdresser in Whitechapel in the East End of London. He was on a list of police suspects but there was never enough evidence to bring him to trial at the time. Later, Kosminski was sent to an asylum where he died at the age of 53 of gangrene of the leg in 1919. In his book, Edwards writes: “ He is no longer just a suspect. My search is over: Aaron Kosminski is Jack the Ripper. ” The most famous serial killer in history has been unmasked, 126 years later. & Reading comprehension: 1. Document : Who is the author of the document? .................................................................................................................. When did he write it? ........................................................................................................................................... Who unmasked Jack the Ripper? ...................................................................................................................... -

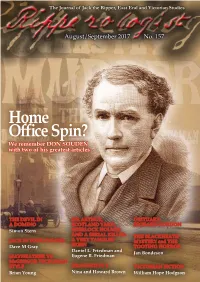

Home Office Spin? We Remember DON SOUDEN with Two of His Greatest Articles

August/September 2017 No. 157 Home Office Spin? We remember DON SOUDEN with two of his greatest articles THE DEVIL IN SIR ARTHUR, OBITUARY: A DOMINO SCOTLAND YARD, RICHARD GORDON Simon Stern SHERLOCK HOLMES AND A SERIAL KILLER: THE BLACKHEATH JACK IN FOUR COLORS A VERY TANGLED MYSTERY and THE Dave M Gray SKEIN TOOTING HORROR Daniel L. Friedman and Jan Bondeson MAYWEATHER VS Eugene B. Friedman McGREGOR VICTORIAN STYLE DRAGNET! PT 1 VICTORIAN FICTION Brian Young Nina and Howard BrownRipperologistWilliam 118 January Hope 2011 Hodgson1 Ripperologist 157 August/September 2017 EDITORIAL: FAREWELL, SUPE Adam Wood PARDON ME: SPIN CONTROL AT THE HOME OFFICE? Don Souden WHAT’S WRONG WITH BEING UNMOTIVATED? Don Souden THE DEVIL IN A DOMINO Simon Stern SIR ARTHUR, SCOTLAND YARD, SHERLOCK HOLMES AND A SERIAL KILLER: A VERY TANGLED SKEIN Daniel L. Friedman and Eugene B. Friedman JACK IN FOUR COLORS Dave M Gray MAYWEATHER VS McGREGOR VICTORIAN STYLE Brian Young OBITUARY: RICHARD GORDON THE BLACKHEATH MYSTERY and THE TOOTING HORROR Jan Bondeson DRAGNET! PT 1 Nina and Howard Brown VICTORIAN FICTION: THE VOICE IN THE NIGHT By William Hope Hodgson BOOK REVIEWS Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.mangobooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. -

{PDF EPUB} the American Murders of Jack the Ripper Tantalizing

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The American Murders of Jack the Ripper Tantalizing Evidence of the Gruesome American Interlude of t Jack the Ripper's identity may finally be known, thanks to DNA. The identity of Jack the Ripper, the notorious serial killer from the late 1800s in England, may finally be known. A DNA forensic investigation published this month by two British researchers in the Journal of Forensic Science identifies Aaron Kosminski, a 23- year-old Polish barber and prime suspect at the time, as the likely killer. The "semen stains match the sequences of one of the main police suspects, Aaron Kosminski," said the study authored by Jari Louhelainen of Liverpool John Moores University and David Miller of the University of Leeds. The murderer dubbed Jack the Ripper killed at least five women from August to November 1888 in the Whitechapel district of London. The study's authors conducted genetic testing of blood and semen on a shawl found near the body of Catherine Eddowes, the killer's fourth victim, whose badly mutilated body was discovered on Sept. 30, 1888. The brutal murders and the mystery behind the killer's identity and motive inspired countless novels, films and theories over the past 130 years. Kosminski, who apparently vanished after the murders, has previously been named as a possible suspect, but his guilt has been a matter of debate and never confirmed. The researchers said they have been analyzing the silk shawl for the past eight years and that to their knowledge "the shawl referred to in this paper is the only piece of physical evidence known to be associated with these murders." Through analysis of fragments of the victim and suspect's mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down solely from one's mother, researchers were able to compare that with samples taken from living descendants of Eddowes and Kosminski. -

Montague John Druitt and the Whitechapel Murders of 1888

‘Yours truly Jack the Ripper’—of New College, Oxford? Montague John Druitt and the Whitechapel Murders of 1888 Montague John Druitt ‘I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet . My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance . Yours truly Jack the Ripper.’ (The ‘Dear Boss’ letter, received by Central News Agency on 27 September 1888) Introduction At around 1 pm, on Monday 31 December 1888, the decomposing body of a man was pulled out of the River Thames at Chiswick in London. Henry Winslade, the waterman who had discovered it, notified the authorities. Large stones placed in the pockets had weighed the body down in the water, keeping it hidden for about a month. Other items found on the body included a silver watch on a gold chain, two cheques (one for £50, a considerable sum, the other for £16), a first- class season rail ticket from Blackheath to London, and the second half of a return ticket from Hammersmith to Charing Cross dated 1 December. 1 New College Notes 7 (2016) ISSN 2517-6935 ‘Yours truly Jack the Ripper’ The body was subsequently identified by the man’s elder brother as Montague John Druitt, a barrister who also worked as an assistant schoolmaster at a boarding school in Blackheath, a former Winchester scholar and graduate of New College, Oxford. At the inquest held on 2 January 1889, Druitt’s brother William, a solicitor living in Bournemouth, described how a friend had told him on 11 December that Montague had not been seen at his chambers for over a week. -

JACK the RIPPER (The Whitechapel Murders)

JACK THE RIPPER (The Whitechapel Murders) OFFICIALS INVOLVED (Police, Government, etc.) 1888 - 1891 Archived by Campbell M Gold (2012) (This material was compiled from various unconfirmed sources) CMG Archives http://campbellmgold.com --()-- Introduction The Whitechapel murders were unprecedented, and the police had no previous cases of this nature to compare. Additionally, the murderer left no clues and seemed to move around and blend effortlessly in with the real Whitechapel of 1888. There were two police forces involved in the investigation to investigate the Whitechapel Murders and to apprehend Jack the Ripper - the Metropolitan Police and the City of London Police. Regarding the Ripper murders, the murders of Mary Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride and Mary Kelly took place in Whitechapel and Spitalfields, and consequently their murder sites came under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police who then investigated these four murders. Catherine Eddowes was murdered on 30 Sept 1888 in Mitre Square, which is in the City of London. Consequently her killing came under the jurisdiction of the City of London Police and was investigated by them. Police Communication Policy Police must not on any account give any information whatever to gentlemen connected with the press, relative to matters within police knowledge, or relative to duties to be performed or orders received, or communicate in any manner, either directly or i9ndirectly, with editors, or 1 reporters of newspapers, on any matter connected with public service, without express and special authority… The slightest deviation from this rule may completely frustrate the ends of justice, and defeat the endeavour of superior officers to advance the welfare of the public service. -

Jack the Ripper - Anonymous Murderer

List of Suspects for Pleasant Places of FL meeting November 2, 2013 Jack the Ripper - Anonymous Murderer It is important to note that Sir Melville Macnaghten, Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in 1889 named three suspects: (1) Aaron Kosminski, a Polish Jew, who lived in Whitechapel and was known to hate women and have strong homicidal tendencies. He was admitted to a lunatic asylum in March 1889; (2) Michael Ostrogg, who was a well-known criminal who spent the majority of his life in prison for theft. He was a con man and sneak thief with 25 or more aliases, and was eventually transferred to a lunatic asylum where he registered himself as a Jewish doctor; and (3) Montague John Druitt, a teacher at a boarding school in Blackheath who was dismissed from his teaching job in late Nov 1888 because of an unspecified ‘serious offence.’ He drowned himself in the Thames in Dec 1888. Macnaghten destroyed all the documents pointing to Druitt. In fact, all Sir Melville Macnaghten's personal files - he headed the CIS and had first hand knowledge of Scotland Yard's entire investigation - simply "vanished" shortly after his death. Inspector Abberline, heading the Ripper investigation, discredited Macnaghten’s suspects. He named his own suspect, George Chapman, whose real name was Severin Klosowski, a Polish barber’s assistant in Whitechapel who poisoned 3 wives and was hanged April 7, 1903. NOTE: Although he named Chapman, Chief Inspector Abberline's presentation walking stick is still preserved at Bramshill Police Staff College where the inscription reveals that the stick was presented to Abberline by his team of detectives at the 'conclusion of the inquiry'. -

Jack the Ripper William D

Article 62 THE HUNT FOR Jack the Ripper William D. Rubinstein reviews the achievements of the ‘Ripperologists’ and lends weight to the argument surrounding the Ripper Diaries. The brutal murders of five prostitutes in London’s East End in known before in Britain. As the killings unfolded, fear gripped the autumn of 1888 by an unknown killer who came to be called the East End, a near-riotous situation developed, and hundreds ‘Jack the Ripper’ are probably the most famous unsolved of extra police were drafted in to patrol the streets of crimes in history. During the past forty years a plethora of the- Whitechapel. Although the Ripper was reportedly seen by sev- ories has been offered as to the identity of the Ripper. In recent eral witnesses, he was never caught, and seemed time and again years, the Ripper industry has mushroomed: it is likely that to slip through the dragnet like magic. While the police had more has been written on this case than on any other staple of many suspects, in the final analysis they remained baffled. amateur historiography (the true identity of Shakespeare and Among those suspected were doctors, or slaughtermen (the, re- the Kennedy assassination possibly excepted). The number of moval of the victims’ organs implied anatomical knowledge), books about Jack the Ripper published internationally shows Jews or other foreigners from the large local community of re- this dramatically: 1888-1909–nine; 1910-49–five; 1950-69– cent immigrants, Fenians, lunatics and eccentrics of all shades, four; 1970-79–ten; 1980-89–twelve; 1990-99–thirty-nine.