National First Peoples Gathering on Climate Change Morgan-Bulled, D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulse March 2020

South West Hospital and Health Service Getting ready for Harmony Week 2020 from Cunnamulla were (clockwise from left) Tina Jackson, Deirdre Williams, Kylie McKellar, Jonathan Mullins, Rachel Hammond Please note: This photo was taken before implementation of social distancing measures. PULSE MARCH 2020 EDITION From the Board Chair Jim McGowan AM 5 From the Chief Executive, Linda Patat 6 OUR COMMUNITIES All in this together - COVID-19 7 Roma CAN supports the local community in the fight against COVID-19 10 Flood waters won’t stop us 11 Everybody belongs, Harmony Week celebrated across the South West 12 Close the Gap, our health, our voice, our choice 13 HOPE supports Adrian Vowles Cup 14 Voices of the lived experience part of mental health forum 15 Taking a stand against domestic violence 16 Elder Annie Collins celebrates a special milestone 17 Shaving success in Mitchell 17 Teaching our kids about good hygiene 18 Students learn about healthy lunch boxes at Injune State School 18 OUR TEAMS Stay Connected across the South West 19 Let’s get physical, be active, be healthy 20 Quilpie staff loving the South West 21 Don’t forget to get the ‘flu’ shot 22 Sustainable development goals 24 Protecting and promoting Human Rights 25 Preceptor program triumphs in the South West 26 Practical Obstetric Multi Professional Training (PROMPT) workshop goes virtual 27 OUR SERVICES Paving the way for the next generation of rural health professionals 28 A focus on our ‘Frail Older Persons’ 29 South West Cardiac Services going from strength to strength 30 WQ Pathways Live! 30 SOUTH WEST SPIRIT AWARD 31 ROMA HOSPITAL BUILD UPDATE 32 We would like to pay our respects to the traditional owners of the lands across the South West. -

Johnathon Davis Thesis

Durithunga – Growing, nurturing, challenging and supporting urban Indigenous leadership in education John Davis-Warra Bachelor of Arts (Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Studies & English) Post Graduate Diploma of Education Supervisors: Associate Professor Beryl Exley Associate Professor Karen Dooley Emeritus Professor Alan Luke Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education Queensland University of Technology 2017 Keywords Durithunga, education, Indigenous, leadership. Durithunga – Growing, nurturing, challenging and supporting urban Indigenous leadership in education i Language Weaves As highlighted in the following thesis, there are a number of key words and phrases that are typographically different from the rest of the thesis writing. Shifts in font and style are used to accent Indigenous world view and give clear signification to the higher order thought and conceptual processing of words and their deeper meaning within the context of this thesis (Martin, 2008). For ease of transition into this thesis, I have created the “Language Weaves” list of key words and phrases that flow through the following chapters. The list below has been woven in Migloo alphabetical order. The challenge, as I explore in detail in Chapter 5 of this thesis, is for next generations of Indigenous Australian writers to relay textual information in the languages of our people from our unique tumba tjinas. Dissecting my language usage in this way and creating a Language Weaves list has been very challenging, but is part of sharing the unique messages of this Indigenous Education field research to a broader, non- Indigenous and international audience. The following weaves list consists of words taken directly from the thesis. -

The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children: an Australian Government Initiative

The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children: An Australian Government Initiative Parent 2 – Wave 2 2009 Mark up Questionnaire This questionnaire is to be completed by a Parent/ Parent Living Elsewhere/ Secondary Care Giver (P2) of the Footprints in Time study child named below. The parent or carer has given written consent to take part in Footprints in Time, a longitudinal study being run by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) on behalf of the Australian Government. P1’s name: ________________________________________________ P2’s name: ________________________________________________ Study child’s name: ________________________________________ Study child’s ID number: respid Has P2 completed a consent form and been given a copy for their records? Yes – please fill in the questionnaire on the CAPI console or on paper No – please ask P2 to complete a consent form All information collected will be kept strictly confidential (except where it is required to be reported by law and/or there is a risk of harm to yourself or others). To ensure that your privacy is maintained, only combined results from the study as a whole will be discussed and published. No individual information will be released to any person or department except at your written request and on your authorisation. Participation in this study is voluntary. If P2 has any questions or wants more information, please ask them to contact the FaHCSIA Footprints in Time Team on 1800 106 235, or they can look at our website at www.fahcsia.gov.au RAO’s name: ____________________________________________________ RAO’s contact details: ____________________________________________ Date entered on Confirmit______________________ R05065 – Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children – Parent 2 Survey – Wave 2, February 2009 – R3.0 1 Table of contents Module 0: Returning ................................................................................................................. -

Senate Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES Senate Official Hansard No. 4, 2005 TUESDAY, 8 FEBRUARY 2005 FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2005 Month Date February 8, 9, 10 March 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17 May 10, 11, 12 June 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23 August 9, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18 September 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15 October 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13 November 7, 8, 9, 10, 28, 29, 30 December 1, 5, 6, 7, 8 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM GOSFORD 98.1 FM BRISBANE 936 AM GOLD COAST 95.7 FM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 747 AM NORTHERN TASMANIA 92.5 FM DARWIN 102.5 FM FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency Major-General Michael Jeffery, Companion in the Order of Australia, Com- mander of the Royal Victorian Order, Military Cross Senate Officeholders President—Senator the Hon. Paul Henry Calvert Deputy President and Chairman of Committees—Senator John Joseph Hogg Temporary Chairmen of Committees—Senators the Hon. -

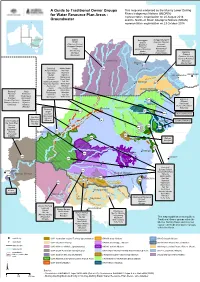

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic Studies of the Cranial Shape The

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic studies of the cranial shape The measurement of the human head of both the living and dead has long been a matter of interest to a variety of professions from artists to physicians and latterly to anthropologists (for a review see Spencer 1997c). The shape of the cranium, in particular, became an important factor in schemes of racial typology from the late 18th Century (Blumenbach 1795; Deniker 1898; Dixon 1923; Haddon 1925; Huxley 1870). Following the formulation of the cranial index by Retzius in 1843 (see also Sjovold 1997), the classification of humans by skull shape became a positive fashion. Of course such classifications were predicated on the assumption that cranial shape was an immutable racial trait. However, it had long been known that cranial shape could be altered quite substantially during growth, whether due to congenital defect or morbidity or through cultural practices such as cradling and artificial cranial deformation (for reviews see (Dingwall 1931; Lindsell 1995). Thus the use of cranial index of racial identity was suspect. Another nail in the coffin of the Cranial Index's use as a classificatory trait was presented in Coon (1955), where he suggested that head form was subject to long term climatic selection. In particular he thought that rounder, or more brachycephalic, heads were an adaptation to cold. Although it was plausible that the head, being a major source of heat loss in humans (Porter 1993), could be subject to climatic selection, the situation became somewhat clouded when Beilicki and Welon demonstrated in 1964 that the trend towards brachycepahlisation was continuous between the 12th and 20th centuries in East- Central Europe and thus could not have been due to climatic selection (Bielicki & Welon 1964). -

Water Management Plan 2020-21: Chapter 3.7 Barwon–Darling

Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Water Management Plan Chapter 3.3 – Warrego and Moonie rivers 2020–21 This document represents a sub-chapter of ‘Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Water Management Plan 2020-21, Commonwealth of Australia, 2020’. Please visit: https://www.environment.gov.au/water/cewo/publications/water-management-plan-2020-21 for links to the main document. Acknowledgement of the Traditional Owners of the Murray–Darling Basin The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners, their Elders past and present, their Nations of the Murray–Darling Basin, and their cultural, social, environmental, spiritual and economic connection to their lands and waters. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Water Management Plan 2020-21 is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This report should be attributed as ‘Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Water Management Plan 2020-21, Commonwealth of Australia, 2020’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright’ noting the third party. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly by, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

The Pulse January / February 2021

South West Hospital and Health Service JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2021 EDITION From the Board Chair 3 Our Teams Board out and about in Charleville, Australia Day honours for Roma Murri CUY 20 Waroona, Augathella and Morven 4 South West welcomes new EDMS 21 From the Acting HSCE 6 New grads start in the South West! 22 Our Communities 7 Mental health care planning 24 First Nations COVID-19 Response Team 7 Take time for your mental wellbeing 24 COVID-19 Vaccine update 8 Our Services Ditch the Durries Stage 2 9 Adrian Vowles Cup 2021 10 New Subacute Unit helps patients across the South West 25 South West’s young people have their say 11 Strategic Plan update 26 Health promotion in Charleville and beyond 12 Healthy Choices for the new year 13 Healthcare Homes’ supporting people in the community 27 Telehealth Portal update 13 Triple P – Online leads to positive child Masterchef comes to Injune 14 and parent outcomes 28 Holiday cooking program 14 Mental Health First Aid workshops for Farewell to Judy Frousheger 15 the South West 28 Building Better relationships on Valentine’s Day 16 Our Resources Smart eating equals healthy ageing 17 Have you visited the Innovation Well? 29 From the travels of Michael Reddan, Community Prevention Officer – Alcohol South West Spirit Award – and Other Drugs 18 Marg Castles (December) Jenny Peacock (January) The new SQRH Training Facility 19 First Nations Covid Response Team (February) 30 Defence Force careers build HOPE 19 Cover image: South West HHS graduate nurses first intake 2021 PULSE January / February 2021 edition | South West Hospital and Health Service 1 We respectfully acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands across the South West. -

Kerwin 2006 01Thesis.Pdf (8.983Mb)

Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author Kerwin, Dale Wayne Published 2006 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1614 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366276 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author: Dale Kerwin Dip.Ed. P.G.App.Sci/Mus. M.Phil.FMC Supervised by: Dr. Regina Ganter Dr. Fiona Paisley This dissertation was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts at Griffith University. Date submitted: January 2006 The work in this study has never previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any University and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this study contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the study itself. Signed Dated i Acknowledgements I dedicate this work to the memory of my Grandfather Charlie Leon, 20/06/1900– 1972 who took a group of Aboriginal dancers around the state of New South Wales in 1928 and donated half their gate takings to hospitals at each town they performed. Without the encouragement of the following people this thesis would not be possible. To Rosy Crisp, who fought her own battle with cancer and lost; she was my line manager while I was employed at (DATSIP) and was an inspiration to me. -

What's in a Name? a Typological and Phylogenetic

What’s in a Name? A Typological and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Names of Pama-Nyungan Languages Katherine Rosenberg Advisor: Claire Bowern Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract The naming strategies used by Pama-Nyungan languages to refer to themselves show remarkably similar properties across the family. Names with similar mean- ings and constructions pop up across the family, even in languages that are not particularly closely related, such as Pitta Pitta and Mathi Mathi, which both feature reduplication, or Guwa and Kalaw Kawaw Ya which are both based on their respective words for ‘west.’ This variation within a closed set and similar- ity among related languages suggests the development of language names might be phylogenetic, as other aspects of historical linguistics have been shown to be; if this were the case, it would be possible to reconstruct the naming strategies used by the various ancestors of the Pama-Nyungan languages that are currently known. This is somewhat surprising, as names wouldn’t necessarily operate or develop in the same way as other aspects of language; this thesis seeks to de- termine whether it is indeed possible to analyze the names of Pama-Nyungan languages phylogenetically. In order to attempt such an analysis, however, it is necessary to have a principled classification system capable of capturing both the similarities and differences among various names. While people have noted some similarities and tendencies in Pama-Nyungan names before (McConvell 2006; Sutton 1979), no one has addressed this comprehensively. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

Salvage Studies of Western Queensland Aboriginallanguages

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series B-1 05 SALVAGE STUDIES OF WESTERN QUEENSLAND ABORIGINALLANGUAGES Gavan Breen Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Breen, G. Salvage studies of a number of extinct Aboriginal languages of Western Queensland. B-105, xii + 177 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1990. DOI:10.15144/PL-B105.cover ©1990 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurrn EDITORIAL BOARD: K.A. Adelaar, T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: BW. Be nder K.A. McElha no n Univers ity ofHa waii Summer Institute of Linguis tics David Bra dle y H. P. McKaughan La Trobe Univers ity Unive rsityof Hawaii Mi chael G.Cl yne P. Miihlhll usler Mo nash Univers ity Bond Univers ity S.H. Elbert G.N. O' Grady Uni ve rs ity ofHa waii Univers ity of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Frank li n K. L. Pike SummerIn stitute ofLingui s tics SummerIn s titute of Linguis tics W.W. Glove r E. C. Po lo me SummerIn stit ute of Linguis tics Unive rsity ofTe xas G.W. Grace Gillian Sa nkoff University ofHa wa ii Universityof Pe nns ylvania M.A.K. Halliday W.A. L.