Water Management Plan 2020-21: Chapter 3.7 Barwon–Darling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule 1 — DETERMINATION AREA A. Description of Determination Area the Determination Area Comprises All of the Land and Wate

Schedule 1 — DETERMINATION AREA A. Description of Determination Area The Determination Area comprises all of the land and waters described in Parts 1, 2 and 3 below, to the extent that they are within the External Boundary Description as described in Part 4 below, and depicted in the map, excluding the areas described in Schedule 2. Part 1 — Exclusive Areas: All of the land and waters described in column 1 of the following table and shown on the determination map described in column 2 of the following table: Area Description Determination Map Sheet Number Lot 10 on CS46 Sheet 1 and Sheet 3 Lot 4 on CS47 Sheet 3 and Sheet 5 Inset 17 Part 2 — Non-Exclusive Areas: (a) The land and waters comprised of the lots and part lots listed in column 1 of the table below and shown on the determination map described in column 2. Area Description Determination Map Sheet Number Lot 55 on B2191 Sheet 5 Inset 1 Lot 37 on B2194 Sheet 5 Inset 1 Lot 61 on B2194 Sheet 5 Inset 1 Lot 11 on B21910 Sheet 5 Inset 1.1 Lot 12 on B21910 Sheet 5 Inset 1.1 Lot 13 on B21910 Sheet 5 Inset 1.1 Lot 14 on B21910 Sheet 5 Inset 1.1 That Part of Lot 4 on BAN100 that falls Sheet 1 within the External Boundary Description Lot 6 on BAN23 Sheet 1 Lot 2 on BEL53167 Sheet 4 Lot 48 on BLM1023 Sheet 5 Inset 1 Lot 49 on BLM1031 Sheet 2 Lot 4 on BLM1089 Sheet 4 Lot 1 on BLM1187 Sheet 5 Inset 1.2 Lot 8 on BLM182 Sheet 5 Inset 12 Area Description Determination Map Sheet Number Lot 3 on BLM255 Sheet 4 Lot 7 on BLM279 Sheet 5 Inset 14 Lot 9 on BLM333 Sheet 5 Inset 3 Lot 2 on BLM339 Sheet 5 -

The Pulse March 2020

South West Hospital and Health Service Getting ready for Harmony Week 2020 from Cunnamulla were (clockwise from left) Tina Jackson, Deirdre Williams, Kylie McKellar, Jonathan Mullins, Rachel Hammond Please note: This photo was taken before implementation of social distancing measures. PULSE MARCH 2020 EDITION From the Board Chair Jim McGowan AM 5 From the Chief Executive, Linda Patat 6 OUR COMMUNITIES All in this together - COVID-19 7 Roma CAN supports the local community in the fight against COVID-19 10 Flood waters won’t stop us 11 Everybody belongs, Harmony Week celebrated across the South West 12 Close the Gap, our health, our voice, our choice 13 HOPE supports Adrian Vowles Cup 14 Voices of the lived experience part of mental health forum 15 Taking a stand against domestic violence 16 Elder Annie Collins celebrates a special milestone 17 Shaving success in Mitchell 17 Teaching our kids about good hygiene 18 Students learn about healthy lunch boxes at Injune State School 18 OUR TEAMS Stay Connected across the South West 19 Let’s get physical, be active, be healthy 20 Quilpie staff loving the South West 21 Don’t forget to get the ‘flu’ shot 22 Sustainable development goals 24 Protecting and promoting Human Rights 25 Preceptor program triumphs in the South West 26 Practical Obstetric Multi Professional Training (PROMPT) workshop goes virtual 27 OUR SERVICES Paving the way for the next generation of rural health professionals 28 A focus on our ‘Frail Older Persons’ 29 South West Cardiac Services going from strength to strength 30 WQ Pathways Live! 30 SOUTH WEST SPIRIT AWARD 31 ROMA HOSPITAL BUILD UPDATE 32 We would like to pay our respects to the traditional owners of the lands across the South West. -

Gauging Station Index

Site Details Flow/Volume Height/Elevation NSW River Basins: Gauging Station Details Other No. of Area Data Data Site ID Sitename Cat Commence Ceased Status Owner Lat Long Datum Start Date End Date Start Date End Date Data Gaugings (km2) (Years) (Years) 1102001 Homestead Creek at Fowlers Gap C 7/08/1972 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 19.9 -31.0848 141.6974 GDA94 07/08/1972 16/12/1995 23.4 01/01/1972 01/01/1996 24 Rn 1102002 Frieslich Creek at Frieslich Dam C 21/10/1976 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 8 -31.0660 141.6690 GDA94 19/03/1977 31/05/2003 26.2 01/01/1977 01/01/2004 27 Rn 1102003 Fowlers Creek at Fowlers Gap C 13/05/1980 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 384 -31.0856 141.7131 GDA94 28/02/1992 07/12/1992 0.8 01/05/1980 01/01/1993 12.7 Basin 201: Tweed River Basin 201001 Oxley River at Eungella A 21/05/1947 Open DWR 213 -28.3537 153.2931 GDA94 03/03/1957 08/11/2010 53.7 30/12/1899 08/11/2010 110.9 Rn 388 201002 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.1 C 27/05/1947 31/07/1957 Closed DWR 124 -28.3151 153.3511 GDA94 01/05/1947 01/04/1957 9.9 48 201003 Tweed River at Braeside C 20/08/1951 31/12/1968 Closed DWR 298 -28.3960 153.3369 GDA94 01/08/1951 01/01/1969 17.4 126 201004 Tweed River at Kunghur C 14/05/1954 2/06/1982 Closed DWR 49 -28.4702 153.2547 GDA94 01/08/1954 01/07/1982 27.9 196 201005 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.3 A 3/04/1957 Open DWR 111 -28.3096 153.3360 GDA94 03/04/1957 08/11/2010 53.6 01/01/1957 01/01/2010 53 261 201006 Oxley River at Tyalgum C 5/05/1969 12/08/1982 Closed DWR 153 -28.3526 153.2245 GDA94 01/06/1969 01/09/1982 13.3 108 201007 Hopping Dick Creek -

Ken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group

R. A .G TO THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN MURRAY DARLING BASIN ROYAL COMMISSION SUBMISSION BY: The Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group. With the permission of the Executive and Members of these Groups. Prepared by: Mark Hutton on behalf of the Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group. Chairman of the Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group and Co Administrator of the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group Mark Hutton NSW Date: 20/04/2018 Index The Effect The Cause The New Broken Hill to Wentworth Water Supply Pipeline Environmental health Floodplain Harvesting The current state of the Darling River 2007 state of the Darling Report Water account 2008/2009 – Murray Darling Basin Plan The effect on our communities The effect on our environment The effect on Indigenous Tribes of the Darling Background Our Proposal Climate Change and Irrigation Extractions – Reduced Flow Suggestions for Improvements Conclusion References (Fig 1) The Darling River How the Darling River and Menindee Lakes affect the Plan and South Australia The Effect The flows along the Darling River and into the Menindee Lakes has a marked effect on the amount of water that flows into the Lower Murray and South Australia annually. Alought the percentage may seem small as an average (Approx. 17% per annum) large flows have at times contributed markedly in times when the Lower Murray River had periods of low or no flow. This was especially evident during the Millennium Drought when a large flow was shepherded through to the Lower Lakes and Coorong thereby averting what would have been a natural disaster and the possibility of Adelaide running out of water. -

National First Peoples Gathering on Climate Change Morgan-Bulled, D

National First Peoples Gathering on Climate Change Morgan-Bulled, D.; Jackson, Guy ; Williams, R.; Morgan-Bulled D, McNeair B, Delaney D, Deshong S, Gilbert J, Mosby H, Neal DP, et al. 2021 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Morgan-Bulled, D., Jackson, G., Williams, R., & Morgan-Bulled D, McNeair B, Delaney D, Deshong S, Gilbert J, Mosby H, Neal DP, et al. (2021). National First Peoples Gathering on Climate Change. Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub . Total number of authors: 4 Creative Commons License: CC BY General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 WORKSHOP REPORT National First Peoples Gathering on Climate Change 18 June 2021 Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub Report No. -

Senate Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES Senate Official Hansard No. 4, 2005 TUESDAY, 8 FEBRUARY 2005 FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2005 Month Date February 8, 9, 10 March 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17 May 10, 11, 12 June 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23 August 9, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18 September 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15 October 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13 November 7, 8, 9, 10, 28, 29, 30 December 1, 5, 6, 7, 8 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM GOSFORD 98.1 FM BRISBANE 936 AM GOLD COAST 95.7 FM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 747 AM NORTHERN TASMANIA 92.5 FM DARWIN 102.5 FM FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency Major-General Michael Jeffery, Companion in the Order of Australia, Com- mander of the Royal Victorian Order, Military Cross Senate Officeholders President—Senator the Hon. Paul Henry Calvert Deputy President and Chairman of Committees—Senator John Joseph Hogg Temporary Chairmen of Committees—Senators the Hon. -

The Profound Response of the Dryland Warrego River, Eastern Australia, to Holocene Hydroclimatic Change Zacchary Larkin

BSG Postgraduate Research Grant – March 2017 A shifting ‘river of sand’: the profound response of the dryland Warrego River, eastern Australia, to Holocene hydroclimatic change Zacchary Larkin Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia [email protected] Project outline Understanding how rivers respond to extrinsic forcing (e.g. hydroclimatic change) is increasingly important given concerns surrounding the changes to climate projected for the coming decades and beyond. However, disentangling changes brought about by extrinsic forcing and those brought about by intrinsic fluvial dynamics can be difficult. A long-term perspective on dryland river development can improve our understanding of fluvial responses to extrinsic forcing and the associated thresholds that influence river behaviour. The Warrego River is a dryland river in the northern Murray-Darling Basin. Little is known about its geomorphology and late Quaternary evolution, however large palaeochannels preserved on the floodplain that have a significantly different morphology to the modern river may provide insight into threshold responses of rivers to changing hydroclimatic conditions. The main aims of this project were to: 1) characterise the hydrology and geomorphology of the modern Warrego River, and 2) to determine the age of large palaeochannels adjacent to the modern river and to characterise their palaeohydrology and geomorphology. 2017 Fieldwork The BSG postgraduate grant provided critical funding to help support an 11-day fieldtrip to the Warrego River in southwest Queensland and northwest New South Wales, Australia. The aim of this fieldwork was to undertake topographic surveys of the Warrego River and to collect samples for optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating from large palaeochannels on the Warrego floodplain. -

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin Animals and Habitat the Basin Supports a Diverse Range of Plants and the Murray–Darling Basin Is Australia’S Largest Animals

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin animals and habitat The Basin supports a diverse range of plants and The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest animals. Over 350 species of birds (35 endangered), and most diverse river system — a place of great 100 species of lizards, 53 frogs and 46 snakes national significance with many important social, have been recorded — many of them found only in economic and environmental values. Australia. The Basin dominates the landscape of eastern At least 34 bird species depend upon wetlands in 1. 2. 6. Australia, covering over one million square the Basin for breeding. The Macquarie Marshes and kilometres — about 14% of the country — Hume Dam at 7% capacity in 2007 (left) and 100% capactiy in 2011 (right) Narran Lakes are vital habitats for colonial nesting including parts of New South Wales, Victoria, waterbirds (including straw-necked ibis, herons, Queensland and South Australia, and all of the cormorants and spoonbills). Sites such as these Australian Capital Territory. Australia’s three A highly variable river system regularly support more than 20,000 waterbirds and, longest rivers — the Darling, the Murray and the when in flood, over 500,000 birds have been seen. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, Murrumbidgee — run through the Basin. Fifteen species of frogs also occur in the Macquarie and despite having one of the world’s largest Marshes, including the striped and ornate burrowing The Basin is best known as ‘Australia’s food catchments, river flows in the Murray–Darling Basin frogs, the waterholding frog and crucifix toad. bowl’, producing around one-third of the are among the lowest in the world. -

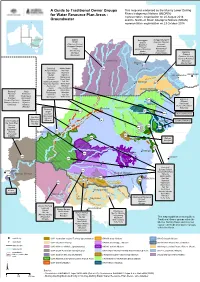

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

Warrego River Scoping Study – Summary

FinalWestern Summary Catchment Management Authority WarregoFinal River Summary Scoping Study 2008 WESTERN Contact Details Western CMA Offices: 45 Wingewarra Street Dubbo NSW 2830 Ph 02 6883 3000 32 Sulphide Street Broken Hill NSW 2880 Ph 08 8082 5200 21 Mitchell Street Bourke NSW 2840 Ph 02 6872 2144 62 Marshall Street Cobar NSW 2835 Ph 02 6836 1575 89 Wee Waa Street Walgett NSW 2832 Ph 02 6828 0110 Freecall 1800 032 101 www.western.cma.nsw.gov.au WMA Head Office: Level 2, 160 Clarence Street Sydney NSW 2000 Ph 02 9299 2855 Fax 02 9262 6208 E [email protected] W www.wmawater.com.au warrego river scoping study - page 2 1. Warrego River Scoping Study – Summary 1.1. Project Rationale and Objectives The Queensland portion of the Warrego is managed under the Warrego, Paroo, Bulloo and Nebine Water Resource Plan (WRP) (2003) and the Resource Operation Plan (ROP) (2006). At present, there is no planning instrument in NSW. As such, there was concern in the community that available information be consolidated and assessed for usability for the purposes of supporting development of a plan in NSW and for future reviews of the QLD plan. There was also concern that an assessment be undertaken of current hydrologic impacts due to water resource development and potential future impacts. As a result, the Western Catchment Management Authority (WCMA) commissioned WMAwater to undertake a scoping study for the Warrego River and its tributaries and effluents. This study was to synthesise and identify gaps in knowledge / data relating to hydrology, flow dependent environmental assets and water planning instruments. -

Annual Operations Plan Barwon-Darling 2019-20 Acronym Definition

Annual Operations Plan Barwon-Darling 2019-20 Acronym Definition AWD Available Water Determination Contents BLR Basic Landholder Rights BoM Bureau of Meteorology CWAP Critical Water Advisory Introduction 2 Panel The Barwon-Darling river system 2 CWTAG Critical Water Technical Unregulated system flow 3 Advisory Group Rainfall trends 3 DPI CDI Department of Primary Water users in the valley 4 Industries - Combined Drought Indicator Water availability 5 DPIE EES Department of Planning, Current drought conditions 6 Industry and Environment Resource assessment in the Northern regulated valleys 7 - Environment, Energy & Science Water resource forecast 9 DPI Department of Primary Barwon-Darling - past 24 month rainfall 9 Fisheries Industries - Fisheries Northern NSW River Systems - past 24 month flows 10 DPIE Department of Planning, Water Industry and Environment Weather forecast - 3 month BoM forecast 12 - Water Barwon-Darling flow 12 FSL Full Supply Level Annual operations 13 HS High Security Barwon-Darling flow class map 13 IRG Incident Response Guide Scenarios 14 ISEPP Infrastructure State Environmental Planning Projects 14 Policy LGA Local Government Areas ROSCCo River Operations Stakeholder Consultation Committee D&S Domestic and Stock vTAG Valley Technical Advisory Group Introduction This plan considers the current volume of water in storages of the tributary catchments and weather forecasts. This plan may be updated as a result significant changes to weather patterns. This year’s plan outlines WaterNSW’s response to the drought in the Barwon-Darling Valley including: • Identification of critical dates. • Our operational response. The NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment’s Extreme Events Policy and Incident Response Guides outlines the 4 stages of drought. -

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic Studies of the Cranial Shape The

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic studies of the cranial shape The measurement of the human head of both the living and dead has long been a matter of interest to a variety of professions from artists to physicians and latterly to anthropologists (for a review see Spencer 1997c). The shape of the cranium, in particular, became an important factor in schemes of racial typology from the late 18th Century (Blumenbach 1795; Deniker 1898; Dixon 1923; Haddon 1925; Huxley 1870). Following the formulation of the cranial index by Retzius in 1843 (see also Sjovold 1997), the classification of humans by skull shape became a positive fashion. Of course such classifications were predicated on the assumption that cranial shape was an immutable racial trait. However, it had long been known that cranial shape could be altered quite substantially during growth, whether due to congenital defect or morbidity or through cultural practices such as cradling and artificial cranial deformation (for reviews see (Dingwall 1931; Lindsell 1995). Thus the use of cranial index of racial identity was suspect. Another nail in the coffin of the Cranial Index's use as a classificatory trait was presented in Coon (1955), where he suggested that head form was subject to long term climatic selection. In particular he thought that rounder, or more brachycephalic, heads were an adaptation to cold. Although it was plausible that the head, being a major source of heat loss in humans (Porter 1993), could be subject to climatic selection, the situation became somewhat clouded when Beilicki and Welon demonstrated in 1964 that the trend towards brachycepahlisation was continuous between the 12th and 20th centuries in East- Central Europe and thus could not have been due to climatic selection (Bielicki & Welon 1964).