Values and Hierarchy in the Study of Balinese Forms of Life: on the Applicability of Dumontian Perspectives and the Ranking of Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penjor in Hindu Communities

Penjor in Hindu Communities: A symbolic phrases of relations between human to human, to environment, and to God Makna penjor bagi Masyarakat Hindu: Kompleksitas ungkapan simbolis manusia kepada sesama, lingkungan, dan Tuhan I Gst. Pt. Bagus Suka Arjawa1* & I Gst. Agung Mas Rwa Jayantiari2 1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Udayana 2Faculty of Law, Universitas Udayana Address: Jalan Raya Kampus Unud Jimbaran, South Kuta, Badung, Bali 80361 E-mail: [email protected]* & [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this article was to observe the development of the social meaning derived from penjor (bamboo decorated with flowers as an expression of thanks to God) for the Balinese Hindus. In the beginning, the meaning of penjor serves as a symbol of Mount Agung, and it developed as a human wisdom symbol. This research was conducted in Badung and Tabanan Regency, Bali using a qualitative method. The time scope of this research was not only on the Galungan and Kuningan holy days, where the penjor most commonly used in society. It also used on the other holy days, including when people hold the caru (offerings to the holy sacrifice) ceremony, in the temple, or any other ceremonial place and it is also displayed at competition events. The methods used were hermeneutics and verstehen. These methods served as a tool for the researcher to use to interpret both the phenomena and sentences involved. The results of this research show that the penjor has various meanings. It does not only serve as a symbol of Mount Agung and human wisdom; and it also symbolizes gratefulness because of God’s generosity and human happiness and cheerfulness. -

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2000 Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Rangoon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Fischer, Joseph, "Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries" (2000). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 803. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/803 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Vanishing Balinese embroideries provide local people with a direct means of honoring their gods and transmitting important parts of their narrative cultural heritage, especially themes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. These epics contain all the heroes, preferred and disdained personality traits, customary morals, instructive folk tales, and real and mythic historic connections with the Balinese people and their rich culture. A long ider-ider embroidery hanging engagingly from the eaves of a Hindu temple depicts supreme gods such as Wisnu and Siwa or the great mythic heroes such as Arjuna and Hanuman. It connects for the Balinese faithful, their life on earth with their heavenly tradition. Displayed as an offering on outdoor family shrines, a smalllamak embroidery of much admired personages such as Rama, Sita, Krisna and Bima reflects the high esteem in which many Balinese hold them up as role models of love, fidelity, bravery or wisdom. -

Anthropometric Study of Nasal Index of the Bali Aga Population

ORLI Vol. 49 No. 1 Tahun 2019 Anthropometric study of nasal index of the Bali Aga population Research Report Anthropometric study of nasal index of the Bali Aga population Agus Rudi Asthuta, I Putu Yupindra Pradiptha Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Faculty of Medicine Udayana University/ Sanglah General Hospital Denpasar ABSTRACT Background: Anthropometry is the measurement of human and more inclined to focus on the dimensions of the human body. Nasal indexes can be used to help determine personal identity, especially race, ethnic and gender differences. Purpose: The general objective of this study was to find out the results of nasal index anthropometric studies on Bali Aga populations in Tenganan. Methods: In this study, 20 samples (4 male and 16 female) within age group of 17-30 years old of Bali Aga population in Tenganan Village were measured strictly on Frankfort’s plane with the help of a sliding caliper. Results: The results of nasal anthropometry measurements obtained an average width of the nose of 38.790 mm, the average nose length of 45.490 mm and nasal index measurements obtained an average of 85.6416. Conclusion: Nasal index can be used to help determine personal identity, especially race, ethnic and gender differences. The result of nasal index in Bali Aga population in Tenganan Village is the Platyrrhine nose (wide nose). Keywords: anthropometry, nasal index, Bali Aga ABSTRAK Latar belakang: Antropometri adalah pengukuran manusia dan lebih cenderung terfokus pada dimensi tubuh manusia. Nasal indeks dapat digunakan untuk membantu menentukan identitas personal, terutama perbedaan ras, etnis, dan jenis kelamin. -

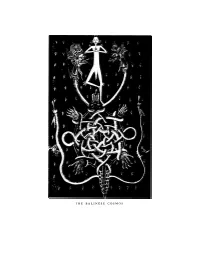

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 192 EduARCHsia & Senvar 2019 International Conference (EduARCHsia 2019) Bali Aga Villages in Kintamani, Inventory of Tangible and Intangible Aspects Ni Made Yudantini Architecture Department Faculty of Engineering, Udayana University Bali, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract— the Indigenous villages in Bali Province is called Sukawana Village. Reuter's research illustrated the rules and Bali Aga, which is interesting to do research in depth to Bali Aga traditions called ulu apad. His research is connected understand the indigenous character of Bali Aga. The Bali Aga to other villages within surrounding the Batur Lake or the villages have their own uniqueness for customs, traditions, Bintang Danu area. Muller’s fieldtrip in 1980s documented 25 culture, and architecture and built environment. These Bali Aga villages in four areas consisting of the center characteristics of the uniqueness in Bali Aga villages are defined mountain, the northern coast of Bali, the center of the southern by the originality of the culture and tradition that are not part of Bali and East Bali. Muller as an anthropologist affected from other culture’s influences. Among eight regencies described her research results through the book that published and one city in Bali Province, Bangli Regency has the highest in 2011 which described the villages were faced on the lack of number of Bali Aga villages, which are about 25 villages. infrastructure, the village’s life depend on dry land causing Kintamani Sub-district is noted to have approximately 19 Bali Aga villages scattered in the foot of Mount Batur, along Lake difficulty in rice production. -

L. Howe Hierarchy and Equality; Variations in Balinese Social Organization In: Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

L. Howe Hierarchy and equality; Variations in Balinese social organization In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Rituals and Socio-Cosmic Order in Eastern Indonesian Societies; Part I Nusa Tenggara Timur 145 (1989), no: 1, Leiden, 47-71 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 01:48:38AM via free access L. E.A.HOWE HIERARCHY AND EQUALITY: VARIATIONS IN BALINESE SOCIAL ÖRGANIZATION Introduction Over the last decade a considerable portion of anthropological writing about Bali has concentrated on the island's history, in particular the development of its politico-religious structure (Geertz 1980; Guermon- prez 1985; van der Kraan 1983; Schulte Nordholt 1986), but also changing western representations of Balinese culture and society (Boon 1977; Schulte Nordholt 1986). This has provided a much needed and very valuable counterbalance to the more a-historical and synchronic studies of Bali characteristic of the postwar period. One issue has, however, been somewhat neglected. This concerns broad variation in forms of social organization. This may seem a rather odd claim, since rriany of the writings of Dutch colonial officers focused on variation, and indeed Korn (1932) devoted his major work to a detailed description of differences in social organization. Geertz (1959), moreover, chose to address this issue in his first published paper on Bali; he argued that observed variation was a result of the different ways in which seven 'organisational themes' could be combined. However, he confined himself to description and example and offered no explanation as to why and how different permutations emerged; and he dismissed as irrelevant a group of mountain villages (Bali Aga) whose social organization is markedly different to that of the plains villages which he had himself studied. -

Indonesia Cruise – Bali to Flores

Indonesia Cruise – Bali to Flores Trip Summary Immerse yourself in Bali, Komodo Island, and Indonesia's Lesser Sunda Islands from an intimate perspective, sailing through a panorama of islands and encountering new wonders on a daily basis. Explore crystalline bays, tribal villages, jungle-clad mountains, and mysterious lakes on this eight- day long Indonesian small-ship adventure. This exciting adventure runs from Flores to Bali or Bali to Flores depending on the week! (Please call your Adventure Consultant for more details). Itinerary Day 1: Arrive in Bali In the morning we will all meet at the Puri Santrian Hotel in South Bali before boarding our minibus for our destination of Amed in the eastern regency of Karangasem – an exotic royal Balinese kingdom of forests and mighty mountains, emerald rice terraces, mystical water palaces and pretty beaches. With our tour leader providing information along the way, we will stop at Tenganan Village, a community that still holds to the ancient 'Bali Aga' culture with its original traditions, ceremonies and rules of ancient Bali, and its unique village layout and architecture. We’ll also visit the royal water palace of Tirta Gangga, a fabled maze of spine-tinglingy, cold water pools and basins, spouts, tiered pagoda fountains, stone carvings and lush gardens. The final part of our scenic the journey takes us through a magnificent terrain of sculptured rice terraces followed by spectacular views of a fertile plain extending all the way to the coast. Guarded by the mighty volcano, Gunung Agung, your charming beachside hotel welcomes you with warm Balinese hospitality and traditional architecture, rich with hand-carved ornamentation. -

Relationship Between Environmental Management Policy and the Local Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples in the Handling of COVID-19 in Indonesia

Relationship between environmental management policy and the local wisdom of indigenous peoples in the handling of COVID-19 in Indonesia OÑATI SOCIO-LEGAL SERIES VOLUME 11, ISSUE 3 (2021), 860–882: INVESTIGATIONS – INVESTIGACIONES – IKERLANAK DOI LINK: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1193 RECEIVED 26 OCTOBER 2020, ACCEPTED 09 FEBRUARY 2021 WAHYU NUGROHO∗ Abstract This paper aims to understand the concept of local wisdom (Indonesian term: kearifan local) from the perspective of Indonesian indigenous peoples (Indonesian term: masyarakat adat) in handling COVID-19 and environmental management policies. In this article, use normative legal research methods, empirical data based on developments in policy and media in Indonesia, and qualitative analysis. The findings of this study are first, constructing local wisdom of Indonesian indigenous peoples in environmental management and handling of COVID-19, based on the teachings of their ancestors and based on the customary calendar as a reference; second, build partnerships related to environmental policies and indigenous peoples by considering the balance of nature and changes in human behavior through local wisdom to reduce carbon emissions during a pandemic. The author is interested in this research because there is an integration of local wisdom of Indonesian indigenous peoples in environmental policies and handling COVID-19. Key words Policy; environmental management; local wisdom; indigenous peoples; COVID- 19 Resumen Este artículo se propone entender el concepto de saber local (término en indonesio: kearifan local) desde la perspectiva de los pueblos indígenas indonesios (término en indonesio: masyarakat adat) para gestionar la COVID-19 y las políticas medioambientales. En el artículo, se usan métodos normativos de investigación jurídica, ∗ Lecturer at the Faculty of Law, Sahid University of Jakarta, interested in the fields of environmental law & policy studies, state administrative law, customary law, and human rights. -

ADARA Honor and Respect

INDONESIAN CULTURAL ESSENCE THROUGH VISUAL ART 1 ADARA honor and respect 2 ADARA 3 ADARA 3 ADARA BACKGROUND ADARA is a platform that specializes on conserving Indo- nesia’s tribes to the modern world. Emphasizing in helping Indonesian endangered culture to grow and to be acknowl- edged, ADARA will feature the latest innovation of technology to showcase the tribes in the endangered culture. Embracing the culture in Indonesia, ADARA is also aiming to increase the awareness on how there are a lot of culture in Indonesia that people are not aware of by educating through art exhibition, fashion show, performing arts or theatre and workshops. ADARA focuses on bringing the endangered culture to be showcased in a bigger scale through the latest form of tech- nology. Not only to the local citizen, ADARA also aiming in introducing Indonesian culture to foreign countries. Through our concept visualization, ADARA have the potential to help the country in increasing the tourism value and also to in- crease the awareness on certain culture. ADARA attempts to introduce the various culture in Indonesia, and mainly for the endangered culture. Besides being the platform that showcases the beauty of Indo- 4 nesians tribes, ADARA also specializes in becoming a creative event organizer to pack events in fusion between the convention- al world and the modern world. ADARA VISION & MISSION VISION ADARA believes that every culture in Indonesia has its beauty that is fascinating for everyone to know, therefore, ADARA is emphasizing in helping the endangered culture. To take the art of endangered culture to be escalated to the next level using the latest innovation of technolo- gy and exposed to a larger scale in order to increase the awareness and educate people, for them to have a broaden knowledge in Indonesian culture and uncon- 5 sciously involving the role of the audience in supporting 5 the endangered culture. -

An Analysis of the Characteristics of Balinese Costume -� Focus� On� The� Legong� Dance� Costume

Print ISSN 1229-6880 Journal of the Korean Society of Costume Online ISSN 2287-7827 Vol. 67, No. 4 (June 2017) pp. 38-57 https://doi.org/10.7233/jksc.2017.67.4.038 An Analysis of the Characteristics of Balinese Costume - Focus on the Legong Dance Costume - Langi, Kezia-Clarissa · Park, Shinmi⁺ Master Candidate, Dept. of Clothing & Textiles, Andong National University Associate Professor, Dept. of Clothing & Textiles, Andong National University⁺ (received date: 2017. 1. 12, revised date: 2017. 4. 11, accepted date: 2017. 6. 16) ABSTRACT1) Traditional costume in Indonesia represents identity of a person and it displays the origin and the status of the person. Where culture and religion are fused, the traditional costume serves one of the most functions in rituals in Bali. This research aims to analyze the charac- teristics of Balinese costumes by focusing on the Legong dance costume. Quantitative re- search was performed using 332 images of Indonesian costumes and 210 images of Balinese ceremonial costumes. Qualitative research was performed by doing field research in Puri Saba, Gianyar and SMKN 3 SUKAWATI(Traditional Art Middle School). The paper illus- trates the influence and structure of Indonesian traditional costume. As the result, focusing on the upper wear costume showed that the ancient era costumes were influenced by animism. They consist of tube(kemben), shawl(syal), corset, dress(terusan), body painting and tattoo, jewelry(perhiasan), and cross. The Modern era, which was shaped by religion, consists of baju kurung(tunic) and kebaya(kaftan). The Balinese costume consists of the costume of participants and the costume of performers. -

Tenganan Heritage As a Model of Common Resource Management for Achieving Sustainability

TENGANAN HERITAGE AS A MODEL OF COMMON RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FOR ACHIEVING SUSTAINABILITY Dr. Ir. Nyoman Utari Vipriyanti, MSi [email protected] Mahasaraswati Denpasar University Abstract Tenganan Pegringsingan village is located in the eastern part of Bali Province area. Tenganan Pegringsinganpeople might not be categorized as environment 'lovers', but they have strong attachement and faithful to their traditions and ancestors. No one from this community could break the traditional law called awig-awig that had been established by their ancestors from hundreds of years ago. The objective of this research is to analyze the heritage effect of Tenganan Pengringsingan on the sustainability of common resources. The emphasize of the study is on the ancient institutions that manage common forest and land in traditional village in Bali. The result of the study shows that Tenganan Pegringsingan’s heritage play a critical role in maintaining traditional values which contribute to the sustainability of their forest. Conservation measures are not only exerted in their own territory, but also in the other side of their village. Even though, they do not understand the purpose of every ceremony that they are practicing, they realize that everything has an ultimate goal for sustainability. They believe that life will sustain if all elements which exist in nature, especially air, heat, and water are in a balanced position. Keyword: Heritage, Traditional Institution, Common Management, Sustainability 1 What is Tenganan Pegringsingan look a like? Tenganan Pegringsingan is a traditional village on the island of Bali. The village is located in District Manggis, Karangasem regency in the east of the island of Bali.