L. Howe Hierarchy and Equality; Variations in Balinese Social Organization In: Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthropometric Study of Nasal Index of the Bali Aga Population

ORLI Vol. 49 No. 1 Tahun 2019 Anthropometric study of nasal index of the Bali Aga population Research Report Anthropometric study of nasal index of the Bali Aga population Agus Rudi Asthuta, I Putu Yupindra Pradiptha Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Faculty of Medicine Udayana University/ Sanglah General Hospital Denpasar ABSTRACT Background: Anthropometry is the measurement of human and more inclined to focus on the dimensions of the human body. Nasal indexes can be used to help determine personal identity, especially race, ethnic and gender differences. Purpose: The general objective of this study was to find out the results of nasal index anthropometric studies on Bali Aga populations in Tenganan. Methods: In this study, 20 samples (4 male and 16 female) within age group of 17-30 years old of Bali Aga population in Tenganan Village were measured strictly on Frankfort’s plane with the help of a sliding caliper. Results: The results of nasal anthropometry measurements obtained an average width of the nose of 38.790 mm, the average nose length of 45.490 mm and nasal index measurements obtained an average of 85.6416. Conclusion: Nasal index can be used to help determine personal identity, especially race, ethnic and gender differences. The result of nasal index in Bali Aga population in Tenganan Village is the Platyrrhine nose (wide nose). Keywords: anthropometry, nasal index, Bali Aga ABSTRAK Latar belakang: Antropometri adalah pengukuran manusia dan lebih cenderung terfokus pada dimensi tubuh manusia. Nasal indeks dapat digunakan untuk membantu menentukan identitas personal, terutama perbedaan ras, etnis, dan jenis kelamin. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 192 EduARCHsia & Senvar 2019 International Conference (EduARCHsia 2019) Bali Aga Villages in Kintamani, Inventory of Tangible and Intangible Aspects Ni Made Yudantini Architecture Department Faculty of Engineering, Udayana University Bali, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract— the Indigenous villages in Bali Province is called Sukawana Village. Reuter's research illustrated the rules and Bali Aga, which is interesting to do research in depth to Bali Aga traditions called ulu apad. His research is connected understand the indigenous character of Bali Aga. The Bali Aga to other villages within surrounding the Batur Lake or the villages have their own uniqueness for customs, traditions, Bintang Danu area. Muller’s fieldtrip in 1980s documented 25 culture, and architecture and built environment. These Bali Aga villages in four areas consisting of the center characteristics of the uniqueness in Bali Aga villages are defined mountain, the northern coast of Bali, the center of the southern by the originality of the culture and tradition that are not part of Bali and East Bali. Muller as an anthropologist affected from other culture’s influences. Among eight regencies described her research results through the book that published and one city in Bali Province, Bangli Regency has the highest in 2011 which described the villages were faced on the lack of number of Bali Aga villages, which are about 25 villages. infrastructure, the village’s life depend on dry land causing Kintamani Sub-district is noted to have approximately 19 Bali Aga villages scattered in the foot of Mount Batur, along Lake difficulty in rice production. -

Indonesia Cruise – Bali to Flores

Indonesia Cruise – Bali to Flores Trip Summary Immerse yourself in Bali, Komodo Island, and Indonesia's Lesser Sunda Islands from an intimate perspective, sailing through a panorama of islands and encountering new wonders on a daily basis. Explore crystalline bays, tribal villages, jungle-clad mountains, and mysterious lakes on this eight- day long Indonesian small-ship adventure. This exciting adventure runs from Flores to Bali or Bali to Flores depending on the week! (Please call your Adventure Consultant for more details). Itinerary Day 1: Arrive in Bali In the morning we will all meet at the Puri Santrian Hotel in South Bali before boarding our minibus for our destination of Amed in the eastern regency of Karangasem – an exotic royal Balinese kingdom of forests and mighty mountains, emerald rice terraces, mystical water palaces and pretty beaches. With our tour leader providing information along the way, we will stop at Tenganan Village, a community that still holds to the ancient 'Bali Aga' culture with its original traditions, ceremonies and rules of ancient Bali, and its unique village layout and architecture. We’ll also visit the royal water palace of Tirta Gangga, a fabled maze of spine-tinglingy, cold water pools and basins, spouts, tiered pagoda fountains, stone carvings and lush gardens. The final part of our scenic the journey takes us through a magnificent terrain of sculptured rice terraces followed by spectacular views of a fertile plain extending all the way to the coast. Guarded by the mighty volcano, Gunung Agung, your charming beachside hotel welcomes you with warm Balinese hospitality and traditional architecture, rich with hand-carved ornamentation. -

Relationship Between Environmental Management Policy and the Local Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples in the Handling of COVID-19 in Indonesia

Relationship between environmental management policy and the local wisdom of indigenous peoples in the handling of COVID-19 in Indonesia OÑATI SOCIO-LEGAL SERIES VOLUME 11, ISSUE 3 (2021), 860–882: INVESTIGATIONS – INVESTIGACIONES – IKERLANAK DOI LINK: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1193 RECEIVED 26 OCTOBER 2020, ACCEPTED 09 FEBRUARY 2021 WAHYU NUGROHO∗ Abstract This paper aims to understand the concept of local wisdom (Indonesian term: kearifan local) from the perspective of Indonesian indigenous peoples (Indonesian term: masyarakat adat) in handling COVID-19 and environmental management policies. In this article, use normative legal research methods, empirical data based on developments in policy and media in Indonesia, and qualitative analysis. The findings of this study are first, constructing local wisdom of Indonesian indigenous peoples in environmental management and handling of COVID-19, based on the teachings of their ancestors and based on the customary calendar as a reference; second, build partnerships related to environmental policies and indigenous peoples by considering the balance of nature and changes in human behavior through local wisdom to reduce carbon emissions during a pandemic. The author is interested in this research because there is an integration of local wisdom of Indonesian indigenous peoples in environmental policies and handling COVID-19. Key words Policy; environmental management; local wisdom; indigenous peoples; COVID- 19 Resumen Este artículo se propone entender el concepto de saber local (término en indonesio: kearifan local) desde la perspectiva de los pueblos indígenas indonesios (término en indonesio: masyarakat adat) para gestionar la COVID-19 y las políticas medioambientales. En el artículo, se usan métodos normativos de investigación jurídica, ∗ Lecturer at the Faculty of Law, Sahid University of Jakarta, interested in the fields of environmental law & policy studies, state administrative law, customary law, and human rights. -

ADARA Honor and Respect

INDONESIAN CULTURAL ESSENCE THROUGH VISUAL ART 1 ADARA honor and respect 2 ADARA 3 ADARA 3 ADARA BACKGROUND ADARA is a platform that specializes on conserving Indo- nesia’s tribes to the modern world. Emphasizing in helping Indonesian endangered culture to grow and to be acknowl- edged, ADARA will feature the latest innovation of technology to showcase the tribes in the endangered culture. Embracing the culture in Indonesia, ADARA is also aiming to increase the awareness on how there are a lot of culture in Indonesia that people are not aware of by educating through art exhibition, fashion show, performing arts or theatre and workshops. ADARA focuses on bringing the endangered culture to be showcased in a bigger scale through the latest form of tech- nology. Not only to the local citizen, ADARA also aiming in introducing Indonesian culture to foreign countries. Through our concept visualization, ADARA have the potential to help the country in increasing the tourism value and also to in- crease the awareness on certain culture. ADARA attempts to introduce the various culture in Indonesia, and mainly for the endangered culture. Besides being the platform that showcases the beauty of Indo- 4 nesians tribes, ADARA also specializes in becoming a creative event organizer to pack events in fusion between the convention- al world and the modern world. ADARA VISION & MISSION VISION ADARA believes that every culture in Indonesia has its beauty that is fascinating for everyone to know, therefore, ADARA is emphasizing in helping the endangered culture. To take the art of endangered culture to be escalated to the next level using the latest innovation of technolo- gy and exposed to a larger scale in order to increase the awareness and educate people, for them to have a broaden knowledge in Indonesian culture and uncon- 5 sciously involving the role of the audience in supporting 5 the endangered culture. -

Tenganan Heritage As a Model of Common Resource Management for Achieving Sustainability

TENGANAN HERITAGE AS A MODEL OF COMMON RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FOR ACHIEVING SUSTAINABILITY Dr. Ir. Nyoman Utari Vipriyanti, MSi [email protected] Mahasaraswati Denpasar University Abstract Tenganan Pegringsingan village is located in the eastern part of Bali Province area. Tenganan Pegringsinganpeople might not be categorized as environment 'lovers', but they have strong attachement and faithful to their traditions and ancestors. No one from this community could break the traditional law called awig-awig that had been established by their ancestors from hundreds of years ago. The objective of this research is to analyze the heritage effect of Tenganan Pengringsingan on the sustainability of common resources. The emphasize of the study is on the ancient institutions that manage common forest and land in traditional village in Bali. The result of the study shows that Tenganan Pegringsingan’s heritage play a critical role in maintaining traditional values which contribute to the sustainability of their forest. Conservation measures are not only exerted in their own territory, but also in the other side of their village. Even though, they do not understand the purpose of every ceremony that they are practicing, they realize that everything has an ultimate goal for sustainability. They believe that life will sustain if all elements which exist in nature, especially air, heat, and water are in a balanced position. Keyword: Heritage, Traditional Institution, Common Management, Sustainability 1 What is Tenganan Pegringsingan look a like? Tenganan Pegringsingan is a traditional village on the island of Bali. The village is located in District Manggis, Karangasem regency in the east of the island of Bali. -

Kawistara, Vol. 2, No. 2, 17 Agustus 2012: 121-139

Kawistara, Vol. 2, No. 2, 17 Agustus 2012: 121-139 INTRODUCTION In the Indonesian context, some would A mid-sixteenth century law text mindlessly say that “agama” refers to the from Java was labeled The agama. In their six “official” religions of Islam, Catholicism, study, M.C. Hoadley and M.B. Hooker Protestantism, Hinduism, Buddhism and refer to “agama” as “traditional learning Confucianism and in the same breath (overgelevered leer) which could apply consider “agama” to be the equivalent in equally to any law book”, drawing particularly meaning to “religion” in general. Although upon Hindu law following J. C. G. Jonker’s we may be able to analyze “agama” in argument (Hoadley and Hooker, 1981: 57- terms of other concepts, such as Judaism or 58). In this regard, “agama” is generally communism, the use of “agama” implies understood as a body of prescriptions. The that all Indonesians acknowledge and accept meaning of “agama” shifted and there was its official meaning, whether they belong to already a binary relationship between the these six formalized religions or not. Such a concepts of “agama” and “adat”: “agama” circumstance cries out for an explanation. here refers to a ‘unified’ Javanese Court legal In the past, to say that something was prescription as opposed to the diverse “adat” “agama” was not there simply to be found; of local peripheries. This reasonable first crack the word “agama” does not occur in all would soon give way to the triadic sphere ethnic societies in Indonesia. There is barely of “agama”, “adat” and “kepercayaan” a vocabulary available in great numbers of discussed later. -

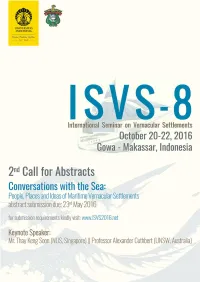

ISVS-8I Nternational

ABSTRACT COMPILATION I n t e r n a t i o n a l S e m i n a r o n V e r n a c u l a r ISVS-8Settlements 2016 Gowa Campus- Hasanuddin University, Makassar-INDONESIA, October 20th-22nd, 2016 International Seminar on Vernacular Settlements CONVERSATION WITH THE SEA:People, Place and Ideas of Maritime Vernacular Settlements October 20th–22nd, 2016, Gowa- Makassar, Indonesia Welcome to Makassar … We wish all participants will find this seminar intellectually beneficial as well as fascinating and looking forward to meeting you all again in future seminars ISVS-8 CONVERSATION WITH THE SEA People, Place and Ideas of Maritime Vernacular Settlements Seminar COMMITTEE Department of Architecture Hasanuddin University CONTENT Content ................................................................................................ i Seminar Schedule ................................................................................ vi Rundown Seminar ............................................................................. viii Parallel Session Schedule .................................................................... ix Abstract Compilation ........................................................................ xvii Theme: The Vernacular and the Idea of “Global” 1. Change in Vernacular Architecture of Goa: Influence of changing priorities from traditional sustainable culture to Global Tourism, by Barsha Amarendra and Amarendra Kumar Das ....................................... 1 2. Emper : Form, Function, And Meaning Of Terrace On Eretan Kulon Fisher -

Textiles in the Exhibition - Ikat

Textiles in the Exhibition - ikat Search this site Home Exhibition Abstract Textiles in the Textiles in the Exhibition Exhibition What is Ikat? <Previous Exhibit Listing Next> How is Ikat Made? Patola Dyes, Controversies North India, traded to Indonesian islands Gender, Exchange Silk, natural dyes, double ikat Healing Textiles Circa 1790s Ikat as Fashion Gift of Anne and John Summerfield Anne and John Summerfield Textile Study Collection Ikat at NGOs Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Art Gallery, College of the Holy Cross 2012 Fieldwork 2006.05.01 Transnational Ikat Exhibition A circa 1790s silk, double ikat patola trade cloth (a study piece, with several holes). This shimmering cloth was originally made in north India and was probably conveyed to the Indonesian islands by Indian merchants, who came to that area in search of spices, aromatic resins and other tropical forest products, and precious metals. Or, the patola could have been brought to the Indonesian islands by Dutch traders in search of the same products. There was a sharp hunger for patola textiles among wealthy royal families in places like coastal Sumatra and Borneo at the height of the patola trade with India, from the 1400s http://sites.holycross.edu/ikat/textiles-in-the-exhibition/exhibitiontextile001[9/27/2017 1:13:29 PM] Textiles in the Exhibition - ikat C.E. and extending for several centuries. The lustrous quality of the silk, the vibrant reds and golds, and especially the sharpness of the motifs in the center fields of these special double ikats entranced local nobles. They displayed their new patola as banners and wrappings for altars and houses, at ceremonial times. -

Study of Folklor Ceremony of Ari-Ari in Bali Aga and Non Bali Aga As a Local Culture of the Lind

Jayapangus Press ISSN 2615-0913 (E) http://jayapanguspress.penerbit.org/index.php/ganaya Vol. 3 No. 2 (2020) Study Of Folklor Ceremony Of Ari-Ari In Bali Aga And Non Bali Aga As A Local Culture Of The Lind Oleh: I Wayan Sujana*, Made Nila Yuwinda Sari , Putu Dian Prima Kusuma Dewi, Putu Agus Windu Yasa Bukian STIKES Buleleng, Bali, Indonesia *[email protected] Keywords: Abstract Folklor; Ari-Ari; Symbolic gratitude for the birth of a baby in Hindu literature is Bali Aga And associated with a series of placenta ceremonies with a system of Non Bali Aga; mendem, drifting into the sea and hanging on a place. The Bali Local Culture Aga community has its own folklore and special characteristics in the procession of the placenta ceremony which is carried out by a hanging system. The basis of folklore is an interesting study in this study to see the basis of the differences in the procession of rituals to get through the middle of Bali Aga with the hanging system and non Bali Aga with the mendem system. This type of research is a qualitative study with a phenomenological approach using observation sheets and indept interviews with traditional leaders, religious leaders and married couples in the Tigawasa and Bungkulan Villages. Data analysis with descriptive qualitative inductive and reduction. The results of this folklore study show that the process of the placenta ceremony carried out by Balinese Non Aga Hindus and Bali Aga Tigawasa are indeed different. Bali Aga has a hanging system on Pigi (a sacred place) without special offerings on the basis of folklore that the placenta is a dirty part while the spirit or soul is still respected during the quarterly ceremony. -

Encountering Asian Art Through Joint

Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal Volume 1 | Number 1 Article 10 1-1-2012 Encountering Asian Art through Joint Faculty- Student Field Research and Museum Curatorship: Ignatian Parallels Susan Rodgers Department of Sociology and Anthropology, College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe Recommended Citation Rodgers, Susan (2012) "Encountering Asian Art through Joint Faculty-Student Field Research and Museum Curatorship: Ignatian Parallels," Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe/vol1/iss1/10 This Scholarship is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rodgers & Cumella: Encountering Asian Art Encountering Asian Art through Joint Faculty-Student Field Research and Museum Curatorship: Ignatian Parallels Susan Rodgers Department of Sociology and Anthropology, College of the Holy Cross ([email protected]) Robin Cumella Student, College of the Holy Cross (Class of 2011) ([email protected]) Abstract The early Jesuits placed the arts at the center of their pedagogy and worldview. Taking cues from such Ignatian teachings on crossing cultural boundaries with respect and humility, and on the an emphasis on the centrality of art in human life, this article reports on a recent ethnographic fieldwork-based encounter with the Balinese arts, specifically ritual textile dyeing and weaving in the village of Tenganan Pegeringsingan, east Bali. This fieldwork on geringsing ceremonial cloth went toward a small college exhibition at the College of the Holy Cross in Spring 2011, an exhibition designed to skewer some of the more popular, touristic, fabulist clichés about ―Balinese culture‖ as paradise-like and timeless. -

International Journal of Educational Policies

International Journal of Natural Sciences and Engineering. Volume 4 Nomor 2 2020, pp 47-59 P-ISSN: 2615-1383 E-ISSN: 2549-6395 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.23887/ijnse.v4i2.24781 Exploration and Utilization of Plant Species Based on Social Culture (Hindu Religion Ceremony) in Tenganan Pegringingan Village, Karangasem Regency, Bali Province, Indonesia Nyoman Wijana1*, Sanusi Mulyadiharja2, I Made Oka Riawan3 1234 Lecturer in Department of Bilogy and Marine Fishery, Faculty of Math and Science, Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha, Indonesia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract This research aims to find out (1) the plants that were used in religious ceremonies (Hinduism) in accordance with the Bali Aga Tenganan Pegringsingan culture. 2) the making process of the various means needed in religious ceremonies (Hinduism) related to the utilization of useful plant species in Bukit Kangin Forest, Tenganan Pegringsingan Village. The Research was explorative (vegetation) and socio-system (community) research. The populations of this research were ecosystem aspects and sociosystem aspects. The ecosystem aspects included all of the useful plant species in Bukit Kangin Forest of Tenganan Pegringsingan village. Meawhile, the sociosystem aspects included the village officials, the village public figures and the community of Tenganan Pegringsingan village. The ecosystem sample (the vegetation) used in this research included the plant species in the forest of Tenganan Pegringsingan Village covered by the 1x1m2 sized seedling square, 10x10m2 sized sapling square and 20x20m2 sized square for trees (mature plants). There were 65 squares in total. The sociosystem samples in this research were the village officials, public figures, shamans, offerers, craftsmen, and the public in Tenganan Pegringsingan village.