249 Acculturation and Its Effects on the Religious and Ethnic Values Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penjor in Hindu Communities

Penjor in Hindu Communities: A symbolic phrases of relations between human to human, to environment, and to God Makna penjor bagi Masyarakat Hindu: Kompleksitas ungkapan simbolis manusia kepada sesama, lingkungan, dan Tuhan I Gst. Pt. Bagus Suka Arjawa1* & I Gst. Agung Mas Rwa Jayantiari2 1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Udayana 2Faculty of Law, Universitas Udayana Address: Jalan Raya Kampus Unud Jimbaran, South Kuta, Badung, Bali 80361 E-mail: [email protected]* & [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this article was to observe the development of the social meaning derived from penjor (bamboo decorated with flowers as an expression of thanks to God) for the Balinese Hindus. In the beginning, the meaning of penjor serves as a symbol of Mount Agung, and it developed as a human wisdom symbol. This research was conducted in Badung and Tabanan Regency, Bali using a qualitative method. The time scope of this research was not only on the Galungan and Kuningan holy days, where the penjor most commonly used in society. It also used on the other holy days, including when people hold the caru (offerings to the holy sacrifice) ceremony, in the temple, or any other ceremonial place and it is also displayed at competition events. The methods used were hermeneutics and verstehen. These methods served as a tool for the researcher to use to interpret both the phenomena and sentences involved. The results of this research show that the penjor has various meanings. It does not only serve as a symbol of Mount Agung and human wisdom; and it also symbolizes gratefulness because of God’s generosity and human happiness and cheerfulness. -

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2000 Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Rangoon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Fischer, Joseph, "Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries" (2000). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 803. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/803 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Vanishing Balinese embroideries provide local people with a direct means of honoring their gods and transmitting important parts of their narrative cultural heritage, especially themes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. These epics contain all the heroes, preferred and disdained personality traits, customary morals, instructive folk tales, and real and mythic historic connections with the Balinese people and their rich culture. A long ider-ider embroidery hanging engagingly from the eaves of a Hindu temple depicts supreme gods such as Wisnu and Siwa or the great mythic heroes such as Arjuna and Hanuman. It connects for the Balinese faithful, their life on earth with their heavenly tradition. Displayed as an offering on outdoor family shrines, a smalllamak embroidery of much admired personages such as Rama, Sita, Krisna and Bima reflects the high esteem in which many Balinese hold them up as role models of love, fidelity, bravery or wisdom. -

Tracing the Maritime Greatness and the Formation of Cosmopolitan Society in South Borneo

JMSNI (Journal of Maritime Studies and National Integration), 3 (2), 71-79 | E-ISSN: 2579-9215 Tracing the Maritime Greatness and the Formation of Cosmopolitan Society in South Borneo Yety Rochwulaningsih,*1 Noor Naelil Masruroh,2 Fanada Sholihah3 1Master and Doctoral Program of History, Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University, Indonesia 2Department of History Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University, Indonesia 3Center for Asian Studies, Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University, Indonesia DOI: https://doi.org/10.14710/jmsni.v3i2.6291 Abstract This article examines the triumph of the maritime world of South Borneo and Received: the construction of a cosmopolitan society as a result of the trade diaspora and November 8, 2019 the mobility of nations from various regions. A “liquid” situation has placed Banjarmasin as a maritime emporium in the archipelago which influenced in Accepted: the 17th century. In fact, the expansion of Islam in the 16th to 17th centuries December 8, 2019 in Southeast Asia directly impacted the strengthening of the existing emporium. Thus, for a long time, Banjarmasin people have interacted and even Corresponding Author: integrated with various types of outsiders who came, for example, Javanese, [email protected] Malays, Indians, Bugis, Chinese, Persians, Arabs, British and Dutch. In the context of the maritime world, the people of South Borneo are not only objects of the entry of foreign traders, but are able to become important subjects in trading activities, especially in the pepper trade. The Banjar Sultanate was even able to respond to the needs of pepper at the global level through intensification of pepper cultivation. -

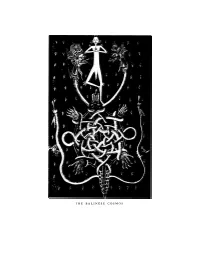

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Basir in Religious System of Dayak Hindu Kaharingan Society

International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Available online at http://sciencescholar.us/journal/index.php/ijssh Vol. 2 No. 2, August 2018, pages: 164~174 e-ISSN: 2550-7001, p-ISSN: 2550-701X https://doi.org/10.29332/ijssh.v2n2.159 Basir in Religious System of Dayak Hindu Kaharingan Society Kuri a, I Putu Gelgel b, I Wayan Budi Utama c Article history: Received 15 March 2018, Accepted in revised form 10 July 2018, Approved 8 August 2018, Available online 11 August 2018 Correspondence Author a Abstract Hinduism developed in Central Kalimantan. It was evidence of Hindu kingdom. It could be seen from the existing history of the oldest Hindu kingdom, namely Kutai kingdom in East Kalimantan in the 4th centuries AD. There was the Yupa- shaped stone found on the banks of the Mahakam River in East Kalimantan. The Yupa stated that the Kutai kingdom. It was a victim pillar stone that was used to bind sacrificial animals during the ceremony. It was provided evidence of the oldest Hindu in Indonesia. It used the Pallawa letter, Sanskrit (Team, 1996: 14). In accordance with the existing evidence of Hindu kingdom in East Kalimantan, it was also seen in Central Kalimantan. The emergence was Hindu Kaharingan teachings. The emergence of Hindu Kaharingan teachings was a religious system Keywords in Dayak society at that time. It was the existence influence of the oldest Hindu kingdom in East Kalimantan. It was developed Hindu Kaharingan teachings in Basir; Central Kalimantan. There was inseparable from the belief system that exists in Dayak; the local Dayak society. -

An Analysis of the Characteristics of Balinese Costume -� Focus� On� The� Legong� Dance� Costume

Print ISSN 1229-6880 Journal of the Korean Society of Costume Online ISSN 2287-7827 Vol. 67, No. 4 (June 2017) pp. 38-57 https://doi.org/10.7233/jksc.2017.67.4.038 An Analysis of the Characteristics of Balinese Costume - Focus on the Legong Dance Costume - Langi, Kezia-Clarissa · Park, Shinmi⁺ Master Candidate, Dept. of Clothing & Textiles, Andong National University Associate Professor, Dept. of Clothing & Textiles, Andong National University⁺ (received date: 2017. 1. 12, revised date: 2017. 4. 11, accepted date: 2017. 6. 16) ABSTRACT1) Traditional costume in Indonesia represents identity of a person and it displays the origin and the status of the person. Where culture and religion are fused, the traditional costume serves one of the most functions in rituals in Bali. This research aims to analyze the charac- teristics of Balinese costumes by focusing on the Legong dance costume. Quantitative re- search was performed using 332 images of Indonesian costumes and 210 images of Balinese ceremonial costumes. Qualitative research was performed by doing field research in Puri Saba, Gianyar and SMKN 3 SUKAWATI(Traditional Art Middle School). The paper illus- trates the influence and structure of Indonesian traditional costume. As the result, focusing on the upper wear costume showed that the ancient era costumes were influenced by animism. They consist of tube(kemben), shawl(syal), corset, dress(terusan), body painting and tattoo, jewelry(perhiasan), and cross. The Modern era, which was shaped by religion, consists of baju kurung(tunic) and kebaya(kaftan). The Balinese costume consists of the costume of participants and the costume of performers. -

The Condition of Freedom of Religion/ Belief in Indonesia 2011

EDITOR: Ismail Hasani The ConditionBonar Tigor Naipospos of Freedom of Religion/ Belief in Indonesia 2011 POLITIK DISKRIMINASI REZIM SUSILO BAMBANG YUDHOYONO Kondisi Kebebasan Beragama/Berkeyakinan di Indonesia 2011 Pustaka Masyarakat Setara The Condition of Freedom of Religion/ Belief in Indonesia 2011 Jakarta, January 2012 155 mm x 230 mm vi + 134 pages ISBN: 978-602-18668-0-1 Writers Agnes Dwi R (Jakarta) Akhol Firdaus (Jawa Timur) Apridon Zaini (Sulawesi Utara) Azhari Aiyub (Aceh) Dewi Nova (Banten) Indra Listiantara (Jakarta) M. Bahrun (NTB) M. Irfan (Jawa Barat) Rochmond Onasis (Kalimantan Tengah) Syarif Abadi (Lampung) Editor Ismail Hasani Bonar Tigor Naipospos Layout Titikoma-Jakarta Cover source www.matanews.com Diterbitkan oleh Pustaka Masyarakat Setara The Condition of Freedom of Religion/ Belief in Indonesia 2011 Foreword The freedom of religion / belief condition report in Indonesia in 2011 was presented to the public on December 19, 2011. However, due to various resource constraints this report has just been published in February 2012. As a monitoring report, this publication is intended in order to expand the spectrum of readers and the expansion of Setara community constituency to jointly advocate the freedom of religion / belief in Indonesia. The report titled Discrimination Politics in the Regime of Soesilo Bambang Yudhoyono, is the fifth report since 2007 SETARA Institute publishes an annual report. As written in previous reports, the events of freedom of religion / belief violations reported by using the standard method and recording. Regular modifications madefor the current themes which becomes the tendency in the particular recent years. This time, the report contains nine kinds of topics of discrimination and violence targeting religious groups / beliefs, and spread in different areas. -

The Adaptation Strategy of Central Kalimantan's Dayak Ngaju Religious System to the State Official Religions in Palangka Raya

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture Available online at https://sloap.org/journals/index.php/ijllc/ Vol. 7, No. 3, May 2021, pages: 111-119 ISSN: 2455-8028 https://doi.org/10.21744/ijllc.v7n3.1470 The Adaptation Strategy of Central Kalimantan’s Dayak Ngaju Religious System to the State Official Religions in Palangka Raya Nali Eka a I Wayan Suka Yasa b I Wayan Budi Utama c Article history: Abstract The findings show that the integration and adaptation of Dayak Ngaju Submitted: 18 February 2021 religious system adherents to Hinduism were done because of both internal Revised: 9 March 2021 and external factors. The internal factor includes the need for recognition of Accepted: 1 April 2021 their basic rights in religion as well as a desire for changes, pioneered by intellectuals and leaders of Dayak Ngaju religious system. The external factor includes religious politics, economy, education, religious conversion, as well as the existence of Great Council of Kaharingan Hinduism and the role of Keywords: State Hindu College of Tampung Penyang Palangka Raya. The adaptation adaptation strategy; strategies are indicated through accommodative behaviors, revitalization, and dayak ngaju religious system; revitalization, as well as resistance. The adaptation strategies imply that the state officials religion; adherents of Dayak Ngaju religious system can maintain Kaharingan identity by calling the religion “Hindu Kaharingan”, even though in state administration, the religion is still written as Hinduism. In daily practice, the teachings of Dayak Ngaju religious system can be delivered in its entirety, and the adherents may still have their rights in religious practices, education, economy, and politics just like the adherents of Indonesian official religions. -

Chinese Indonesians in the Eyes of the Pribumi Public

ISSUE: 2017 No. 73 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 27 September 2017 Chinese Indonesians in the Eyes of the Pribumi Public Charlotte Setijadi* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The racist rhetoric seen in the Ahok blasphemy case and during the Jakarta gubernatorial election held earlier this year sparked fresh concerns about growing anti-Chinese sentiments in Indonesia. To gauge public sentiments towards the ethnic Chinese, questions designed to prompt existing perceptions about Chinese Indonesians were asked in the Indonesia National Survey Project (INSP) recently commissioned by ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. The majority of pribumi (‘native’) survey respondents agreed to statements about Chinese Indonesians’ alleged economic dominance and privilege, with almost 60% saying that ethnic Chinese are more likely than pribumi Indonesians to be wealthy. The survey confirmed the existence of negative prejudice against ethnic Chinese influence in Indonesian politics and economy, and many pribumi believe that Chinese Indonesians may harbour divided national loyalties. * Charlotte Setijadi is Visiting Fellow in the Indonesia Studies Programme, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. This is the fourth in the series based on the Indonesia National Survey Project, published under ISEAS’ Trends in Southeast Asia, available at https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/trends-in-southeast-asia. 1 ISSUE: 2017 No. 73 ISSN 2335-6677 ANTI-CHINESE SENTIMENTS IN INDONESIA Chinese Indonesians have received considerable public attention in the past year, mostly because of the Jakarta gubernatorial election and blasphemy controversy involving Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama. A popular governor with consistently high approval ratings, Ahok, a Chinese and a Christian, was widely tipped to win the 2017 Jakarta election held earlier this year. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 512 Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Folklore, Language, Education and Exhibition (ICOFLEX 2019) Bandung-Born Balinese and Their Effort in Maintaining Balinese Language Oom Rohmah Syamsudin1* 1English Education Program Universitas Indraprasta PGRI, Jakarta, Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study aims to explore the language attitude of Bandung-born Balinese teenagers and their efforts to preserve their local wisdom. The research has been conducted with the descriptive method. The data obtained from questionnaires and interviews indicate that the Balinese youth’s efforts have been remarkable since they tend to maintain their mother tongue, Balinese, daily at home or when speaking with fellow Balinese residents in Bandung. The language shifts to Indonesian language are due to the interlocutor inability to speak Balinese. Their endeavors to conserve their local wisdom can be observed from their typical Balinese names, wearing traditional clothes on religious ritual events, practice Balinese dance and traditional music instruments, and their habit of consuming Balinese culinary whenever an occasion presents itself. Keywords: Language maintenance, Balinese youth in Bandung, Balinese local wisdom studies, or move out of Bali due to work matters. Adult speakers are already "well equipped" or have "complete" 1. INTRODUCTION Balinese language skills. Unlike the use of other regional languages in Indonesia, Balinese is used in almost every Everyday communication between society in Bali aspect of the speaker's life. Important events such as usually uses Balinese language. 85% of Indonesian use religious ceremonies and ritual activities such as their mother tongue in daily communication [1]. -

The Dayaknese Ceremony of Hindu Kaharingan Religion

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.8, No.11, 2018 The Revealed Value and Meaning of Accountability: The Dayaknese Ceremony of Hindu Kaharingan Religion Astrid Patricia Amiani Faculty of Economics and Business, Airlangga University, Indonesia Abstract This study aims to understand the value of the cost sacrifice and the meaning of accountability of the traditional ceremony of death, it’s named Tiwah ceremony for the Dayak people who adhere to the Hindu Kaharingan religion. The cost of carrying out the Tiwah religious ritual is very expensive because of the large number of animals sacrificed, houses for laying bones for the deceased, and other equipment. This study uses an interpretive approach with ethnographic methods.The results of the study found the religious value of divinity, the value of solidarity, socio-economic values and the value of trust as the cost of sacrifice entrusted by the Dayak people who are Hindu Kaharingan. Apart from this, the Tiwah traditional ceremony found affection accountability,social accountability and physical accountability. This means that the Tiwah ceremony's accountability is not only to the community and the deceased but also to Rannying Hatalla Langit Keywords : value of cost sacrifice, accountability, Tiwah ceremony, the Dayaknese 1. Introduction Accounting studies using social analysis based on the interpretive paradigm are an attempt to bring accounting science closer to the reality of culture, religion and spirituality. Individuals and groups are seen as unique in their social life. Within an organization (group / individual) the existing capital is not only seen from the financial aspect but also from the social aspect.