The Crime of Moderation Deep and Self-Inficted Wounds, the Red Army David R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scripting the Revolutionary Worker Autobiography: Archetypes, Models, Inventions, and Marketsã

IRSH 49 (2004), pp. 371–400 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859004001725 # 2004 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Scripting the Revolutionary Worker Autobiography: Archetypes, Models, Inventions, and Marketsà Diane P. Koenker Summary: This essay offers approaches to reading worker autobiographies as a genre as well as source of historical ‘‘data’’. It focuses primarily on one example of worker narrative, the autobiographical notes of Eduard M. Dune, recounting his experiences in the Russian Revolution and civil war, and argues that such texts cannot be utilized even as ‘‘data’’ without also appreciating the ways in which they were shaped and constructed. The article proposes some ways to examine the cultural constructions of such documents, to offer a preliminary typology of lower- class autobiographical statements for Russia and the Soviet Union, and to offer some suggestions for bringing together the skills of literary scholars and historians to the task of reading workers’ autobiographies. In the proliferation of the scholarly study of the autobiographical genre in the past decades, the autobiographies of ‘‘common people’’ have received insignificant attention. Autobiography, it has been argued, is a bourgeois genre, the artifact of the development of modern liberal individualism, the product of individuals with leisure and education to contemplate their selfhood in the luxury of time.1 Peasants, particularly during the time of ‘‘motionless history’’, are judged to constitute ‘‘anti-autobiographical space’’. Workers, whether agricultural, -

The Soviet-German Tank Academy at Kama

The Secret School of War: The Soviet-German Tank Academy at Kama THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ian Johnson Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Jennifer Siegel, Advisor Peter Mansoor David Hoffmann Copyright by Ian Ona Johnson 2012 Abstract This paper explores the period of military cooperation between the Weimar Period German Army (the Reichswehr), and the Soviet Union. Between 1922 and 1933, four facilities were built in Russia by the two governments, where a variety of training and technological exercises were conducted. These facilities were particularly focused on advances in chemical and biological weapons, airplanes and tanks. The most influential of the four facilities was the tank testing and training grounds (Panzertruppenschule in the German) built along the Kama River, near Kazan in North- Central Russia. Led by German instructors, the school’s curriculum was based around lectures, war games, and technological testing. Soviet and German students studied and worked side by side; German officers in fact often wore the Soviet uniform while at the school, to show solidarity with their fellow officers. Among the German alumni of the school were many of the most famous practitioners of mobile warfare during the Second World War, such as Guderian, Manstein, Kleist and Model. This system of education proved highly innovative. During seven years of operation, the school produced a number of extremely important technological and tactical innovations. Among the new technologies were a new tank chassis system, superior guns, and - perhaps most importantly- a radio that could function within a tank. -

Russia's Use of Cyber Warfare in Estonia, Georgia and Ukraine

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2019 War of Nerves: Russia's Use of Cyber Warfare in Estonia, Georgia and Ukraine Madelena Anna Miniats Bard Colllege, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2019 Part of the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Miniats, Madelena Anna, "War of Nerves: Russia's Use of Cyber Warfare in Estonia, Georgia and Ukraine" (2019). Senior Projects Spring 2019. 116. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2019/116 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. War of Nerves: Russia’s Use of Cyber Warfare in Estonia, Georgia and Ukraine Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Global and International Studies of Bard College By Madelena Miniats Annandale-on-Hudson, NY May 2019 Miniats 1 Abstract ________________________________ This project examines how Soviet military thought has influenced present day Russian military doctrine and has evolved to include cyber warfare as part of the larger structure of Russian information warfare. -

Zinoviev (Biography + Primary Sources)

Gregory Zinoviev was born in Yelizavetgrad, Ukraine, Russia on 23rd September, 1883. The son of a Jewish diary farmers, Zinoviev received no formal schooling and was educated at home. At the age of fourteen he found work as a clerk. Zinoviev joined the Social Democratic Party in 1901. He became involved in trade union activities and as a result of police persecution he left Russia and went to live in Berlin before moving on to Paris. In 1903 Zinoviev met Vladimir Lenin and George Plekhanov in Switzerland. At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Party in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Vladimir Lenin and Jules Martov, two of the party's main leaders. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with alarge fringe of non-party sympathisers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Martov won the vote 28-23 but Lenin was unwilling to accept the result and formed a faction known as the Bolsheviks. Those who remained loyal to Martov became known as Mensheviks. Leon Trotsky, who got to know him during this period compared him to Lev Kamenev: "Zinoviev and Kamenev are two profoundly different types. Zinoviev is an agitator. Kamenev a propagandist. Zinoviev was guided in the main by a subtle political instinct. Kamenev was given to reasoning and analyzing. Zinoviev was always inclined to fly off at a tangent. Kamenev, on the contrary, erred on the side of excessive caution. Zinoviev was entirely absorbed by politics, cultivating no other interests and appetites. -

Lenin and Clausewitz: the Militarization of Marxism, 1914-1921

- : Clausewitlz - - t .:~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~w w e.;.. .... ....... ..... ... .: . S. The A ir~~~~~~~~~~~~~........ ..... Mpilitarization of Marxismn, 19m14-i1921 ........1.k. by Jacob W. Kipp Kansas State University Carlvon Clausewitz. Lithograph by F. Michelisafterthe paintingby W. Wach, 1830. (Original in the possession of Professor Peter Paret, Stanford;used with permission.) EVEN the most superficialreading of Soviet militarywrit- old regime. On the one hand, reformersand revolutionaries ings would lead to the conclusion that a close tie exists shared the strong anti-militaristthrust of European Social between Marxism-Leninismand Clausewitz' studies on war Democracy, which viewed the militaryelite as the sources of a and statecraft.Although labeled an "idealist," Clausewitz en- vile and poisonous militarism.The professionalsoldiers' desire joys a place in the Soviet pantheonof militarytheorists strik- for glory,like the capitalists' search for profits,only brought inglysimilar to that assigned to pagan philosophersin Dante's sufferingto the workingclass. All socialists shared a com- Hell. Colonel General I. E. Shavrov, formercommander of the mitmentto a citizens' militiaas the preferredmeans of national Soviet General Staff Academy, has writtenthat Clausewitz' defense. In 1917 the Bolsheviks rode this anti-militaristsen- method marked a radical departurein the study of war: timentto power by supportingthe process of militarydisin- tegration,upholding the chaos of thekomitetshchina, and prom- He, in reality,for the firsttime in militarytheory, denied ising a governmentthat would bringimmediate peace.3 the "eternal" and "unchanging" in militaryart, stroveto These Social Democrats were also the heirs of examine the phenomenonof war in its interdependence the volumi- and interconditionality,in its movement and develop- nous writingson militaryaffairs of the two foundersof scientific ment in order to postulate theirlaws and principles.' socialism, Karl Marx and FriedrichEngels. -

Labor in the Russian Revolution

Labor in the Russian Revolution: Factory Committees and Trade Unions, 1917- 1918 by Gennady Shkliarevsky; Soviet State and Society between Revolutions, 1918-1929 by Lewis H. Siegelbaum; Mary McAuley; The Electrification of Russia, 1880-1926 by Jonathan Coopersmith Review by: Stephen Kotkin The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Jun., 1995), pp. 518-522 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2125137 . Accessed: 10/12/2011 17:28 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern History. http://www.jstor.org 518 Book Reviews analyze more deeply the interplay (critical in all revolutionary situations) between street politics and institutional politics and the ways the two created or prevented possibilities for different revolutionaryconclusions. But no criticism should detract from the great achievement of this major work. It will surely become the standardsource on these events for years to come and should be a useful resource for all historians interestedin modern Russian history. JOAN NEUBERGER Universityof Texas at Austin Labor in the Russian Revolution: Factory Committees and Trade Unions, 1917-1918. -

Draft: Not for Citation Witi:Iout Permission of the Author

DRAFT: NOT FOR CITATION WITI:IOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR NUMBER 143 MYTii Al'ID AUTHORITY IN EARLY SOVIET CULTURE Robert C. Williams Conference on THE ORIGINS OF SOVIET CULTURE Sponsored by Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies The Wilson Center May 18-19, 1981 MYTH fu~ AUTHORITY IN EARLY SOVIET CULT~RE Robert C. williams Washington University* Given this doctrine of experience, united with of symbolism, every religion, even that of paganism, must be held to be true. Pope Pius X, Pascendi Gregis September 1907 If truth is only an organizing form of human experience, then the teaching, say, of Catholicism is also true. V. I. Lenin, Materialism and Empiriocriticism April 1909 Marxism, the ideology of the most progressive class, must reject absolute kriowledge in any system of ideas, including its own. A. A. Bogdanov, Vera i nauka 1910 Early Soviet culture, like Bolshevism, was deeply divided. We may define this division in a number of ways: party versus proletariat; heroism versus utopianism; Leninism versus left Bolshevism; Jacobinism versus syndicalism; consciousness versus spontaneity; Narkompros versus Proletkult; organizatio~ versus experience; vanguard versus collective,l All such divisions ultimately come down to a central Bolshevik disagreement as to whether a socialist society should be grounded in myth or authority. *A paper presented at the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studiesr conference on "The Origins of Soviet Culture, 11 held at the 1>/oodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C., May 18-19, 1981. 1 2 In speaking of myth and authority as two antagonistic and complementary poles of early Soviet culture I am distinguishing between two fundamental ways of organizing our experience: by finding personally satisfactory answers to ultimate questions; second, by accepting socially satisfactory answers to secular needs. -

Final+Russia+Dossier.Pdf

Dossier Count Vladimir Kokovtsov1 -- was a Russian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Russia from 1911. Staunch and conservative, he is one of the most powerful figures in Russia and deals with matters with a trusted iron hand. He is extremely intolerant of the left or any of his opponents--political or otherwise, and often deals with them fatally. As prime minister, he has significant influence over the Duma, the lawmaking body in the Russian empire. He also has significant influence over Tsar Nicholas II, serving as one of his closest advisors. Prince Georgy Lvov2-- a Russian statesman and a supporter of reform, Lvov joined the liberal Constitutional Democratic Party. In 1906 he won election to the Duma. A serial playboy, Georgy touts liberal values loud and proud much to the annoyance of powerful conservatives who see him as an enemy to the future of Russia. He organized work relief efforts during the Russo-Japanese war in 1893, thus he has a fair amount of influence over veterans from this war. He believes in progressive ideals, and thinks that Russia needs to move forward. He believes that Tsar Nicholas might be incompetent and may need replacement. Vasily Shulgin3-- a Russian conservative monarchist, in 1907 Shulgin became a member of the Duma. He advocated right-wing views, supported the government of Pyotr Stolypin, including introduction of courts-martial, and other controversial changes. A strict, powerful political presence in Russia, he is a staunch believer in Machiavellian ethics and is willing to do whatever it takes to bring a highly conservative future to Russia. -

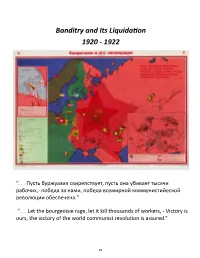

Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic Print, 64 X 102 Cm

Banditry and Its Liquidation 1920 - 1922 “. Пусть буржуазия свирепствует, пусть она убивает тысячи рабочих,- победа за нами, победа всемирной коммунистийеской революции обеспечена.” “. Let the bourgeoisie rage, let it kill thousands of workers, - Victory is ours, the victory of the world communist revolution is assured.” 62 Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic print, 64 x 102 cm. Compilers: A. N. de-Lazari and N. N. Lesevitskii Artist: S. R. Zelikhman Historical Background and Thematic Design The Russian Civil War did not necessarily end with the defeat of the Whites. Its final stage involved various independent bands of partisans and rebels that took advantage of the chaos enveloping the country and contin- ued to operate in rural areas of Ukraine, Tambov Province, the lower Volga, and western Siberia, where Bol- shevik authority was more or less tenuous. Their leaders were by and large experienced military men who stoked peasant hatred for centralized authority, whether it was German occupation forces, Poles, Moscow Bol- sheviks, or Jews. They squared off against the growing power of the communists, which is illustrated as series of five red stars extending over all four sectors. The red circle identifies Moscow as the seat of Soviet power, while the five red stars, enlarging in size but diminishing in color intensity as they move further from Moscow, represent the increasing strength of Communism in Russia during the years 1920-22. The stars also serve as symbolic shields, apparently deterring attacking forces that emanate from Poland, Ukraine, and the Volga region. The red flag with the gold emblem of the hammer-and-sickle in the upper hoist quarter, and the letters Р. -

The White Poles and Wrangel April – November 1920

The White Poles and Wrangel April – November 1920 “. Раз дело дошло до войны, все интересы страны и ее внутренняя жизнь должны быть подчинены войне.” “. Before the matter of the war is finished, all interests of the country and internal considerations must be subordinated to the war.” 55 Map 9 The White Poles and Wrangel // April – November 1920 Colored Lithographic print, 64 x 101 cm. Compilers: A. N. de-Lazari and N. N. Lesevitskii Artist: A. A. Baranov Historical Background As the title of the map indicates, the Soviets maintained that the Poles and the counterrevolutionary White forces operated as allies. Though possessing more or less the same goal, that of defeating the Bolsheviks, the two sides pursued different agendas, as well as withheld military and political assistance from each other, thus foregoing mutual victory. The most salient features of the map are the application of the colors red and white, as well as the use of pho- tomontage. Red and white, in their variations of density, shading, and force, give the illusion of having been applied in broad brushstrokes of watercolor. Russia is engulfed by an imaginary fireball, which originates near the attack of the Red Army on White positions in the Kuban, and spreads across the nation. The incorpo- ration of photographic cut-outs also gives the illusion that the map is a construction of multi-media. The pho- tographic images depict major protagonists of the period: Bolsheviks and their enemies. The chief antagonist to Bolshevik aims was Marshal Jozef Piłsudski, Poland’s Head-of-State, who is pictured on the Polish flag. -

The German Blitzkrieg Against the USSR, 1941

BELFER CENTER PAPER The German Blitzkrieg Against the USSR, 1941 Andrei A. Kokoshin PAPER JUNE 2016 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover image: A German map showing the operation of the German “Einsatzgruppen” of the SS in the Soviet Union in 1941. (“Memnon335bc” / CC BY-SA 3.0) Statements and views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America BELFER CENTER PAPER The German Blitzkrieg Against the USSR, 1941 Andrei A. Kokoshin PAPER JUNE 2016 About the Author Andrei Kokoshin is a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and dean of Moscow State University’s Faculty of World Politics. He has served as Russia’s first deputy defense minister, secretary of the Defense Council and secretary of the Security Council. Dr. Kokoshin has also served as chairman of the State Duma’s Committee on the CIS and as first deputy chairman of the Duma’s Committee on Science and High Technology. Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................vi Introduction .............................................................................. 1 Ideology, Political Goals and Military Strategy of Blitzkrieg in 1941 ..................................................................3 -

Abstract the Chapaevization of Soviet Civil War Memory

ABSTRACT THE CHAPAEVIZATION OF SOVIET CIVIL WAR MEMORY, 1922-1941 by Ivan M. Grek This thesis argues that the creation of the myth about Chapaev was not only a cultural and propagandistic blueprint, but also a memory project, which established a mnemonic pattern for the commemoration of the Civil War. “The chapaevization of memory” consisted of retrofitting the past to the demands of Stalinism and creating a pattern for introducing similar personalities into the pantheon of Civil War heroes. Soviet history absorbed the fictional image of Chapaev and later of others like him as a means to commemorate the Civil War and effecting erase of the Great War. The transition of Chapaev from a figure in popular culture to one in official historical narration paved the way for the advancement of other fallen revolutionaries, such as Nikolai Shchors, Aleksandr Parkhomenko, and Grigorii Kotovskii. The chapaevization of memory became a mnemonic project, which strengthened Stalinism by creating a “proper” memory of the glorious war past. THE CHAPAEVIZATION OF SOVIET CIVIL WAR MEMORY, 1922-1941 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Ivan M. Grek Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2015 Advisor Stephen Norris Reader Robert Thurston Reader Erik Jensen ©2015 Ivan M. Grek This thesis titled THE CHAPAEVIZATION OF SOVIET CIVIL WAR MEMORY, 1922-1941 by Ivan M. Grek has been approved for publication by College of Arts and Sciences and Department of History ___________________________________________________ Stephen Norris, Advisor ___________________________________________________ Robert Thurston, Reader ___________________________________________________ Erik Jensen, Reader Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................