Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blacks and Asians in Mississippi Masala, Barriers to Coalition Building

Both Edges of the Margin: Blacks and Asians in Mississippi Masala, Barriers to Coalition Building Taunya Lovell Bankst Asians often take the middle position between White privilege and Black subordination and therefore participate in what Professor Banks calls "simultaneous racism," where one racially subordinatedgroup subordi- nates another. She observes that the experience of Asian Indian immi- grants in Mira Nair's film parallels a much earlier Chinese immigrant experience in Mississippi, indicatinga pattern of how the dominantpower uses law to enforce insularityamong and thereby control different groups in a pluralistic society. However, Banks argues that the mere existence of such legal constraintsdoes not excuse the behavior of White appeasement or group insularityamong both Asians and Blacks. Instead,she makes an appealfor engaging in the difficult task of coalition-buildingon political, economic, socialand personallevels among minority groups. "When races come together, as in the present age, it should not be merely the gathering of a crowd; there must be a bond of relation, or they will collide...." -Rabindranath Tagore1 "When spiders unite, they can tie up a lion." -Ethiopian proverb I. INTRODUCTION In the 1870s, White land owners recruited poor laborers from Sze Yap or the Four Counties districts in China to work on plantations in the Mis- sissippi Delta, marking the formal entry of Asians2 into Mississippi's black © 1998 Asian Law Journal, Inc. I Jacob A. France Professor of Equality Jurisprudence, University of Maryland School of Law. The author thanks Muriel Morisey, Maxwell Chibundu, and Frank Wu for their suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this Article. 1. -

Spiritual Disciplines of Early Adventists Heather Ripley Crews George Fox University, [email protected]

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2016 Spiritual Disciplines of Early Adventists Heather Ripley Crews George Fox University, [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Crews, Heather Ripley, "Spiritual Disciplines of Early Adventists" (2016). Doctor of Ministry. Paper 139. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/139 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY SPIRITUAL DISCIPLINES OF EARLY ADVENTISTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GEORGE FOX EVANGELICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY LEADERSHIP AND SPIRITUAL FORMATION BY HEATHER RIPLEY CREWS PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Heather Ripley Crews All rights reserved. ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the Biblical spirituality of the early Adventist Church in order to apply the spiritual principles learned to the contemporary church. Though it is God who changes people, the early Adventists employed specific spiritual practices to place themselves in His presence. Research revealed five main spiritual disciplines that shaped the Advent leaders and by extension the church. The first is Bible study: placing the Holy Scriptures as the foundation for all beliefs. The second is prayer: communication and communion with God. -

Xenophobia, Nativism and Pan-Africanism in 21St Century Africa

H-Africa Xenophobia, Nativism and Pan-Africanism in 21st Century Africa Document published by Sabella Abidde on Wednesday, June 17, 2020 cfp-2-xenophobianativismpanafricanism.pdf cfp-2-xenophobianativismpanafricanism.pdf Description: CALL FOR BOOK CHAPTERS Xenophobia, Nativism and Pan-Africanism in 21st Century Africa Sabella Abidde and Emmanuel Matambo (Editors) The purpose of this project is to examine the mounting incidence of xenophobia and nativism across the African continent. Second, it seeks to examine how invidious and self-immolating xenophobia and nativism negate the noble intent of Pan-Africanism. Finally, it aims to examine the implications of the resentments, the physical and mental attacks, and the incessant killings on the psyche, solidarity, and development of the Black World. According to Michael W. Williams, Pan-Africanism is the cooperative movement among peoples of African origin to unite their efforts in the struggle to liberate Africa and its scattered and suffering people; to liberate them from the oppression and exploitation associated with Western hegemony and the international expansionism of the capitalist system. Xenophobia, on the other hand, is the loathing or fear of foreigners with a violent component in the form of periodic attacks and extrajudicial killings committed mostly by native-born citizens. Nativism is the policy and or laws designed to protect the interests of native-born citizens or established residents. The project intends to argue that xenophobia and nativism negate the intent, aspiration, and spirit of Pan-Africanism as expressed by early proponents such as Edward Blyden, W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, George Padmore, Léopold Senghor, Jomo Kenyatta, Aimé Césaire, and Kwame Nkrumah. -

Identification of Seventh-Day Adventist Health Core Convictions : Alignment with Current Healthcare Practice

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2006 Identification of Seventh-day Adventist Health Core Convictions : Alignment with Current Healthcare Practice Randall L. Haffner Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Health and Medical Administration Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Haffner, Randall L., "Identification of Seventh-day Adventist Health Core Convictions : Alignment with Current Healthcare Practice" (2006). Dissertations. 424. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/424 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University School of Education IDENTIFICATION OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST HEALTH CORE CONVICTIONS: ALIGNMENT WITH CURRENT HEALTHCARE PRACTICE A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Randall L. Haffner June 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3234102 Copyright 2006 by Haffner, Randall L. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Immigration Policy As a Defense of White Nationhood

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2020 Immigration Policy as a Defense of White Nationhood Juan F. Perea Loyola University Chicago School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Juan F. Perea, Immigration Policy as a Defense of White Nationhood, 12 GEO. J. L. & MOD. CRITICAL RACE PERSPEC. 1 (2020). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE Immigration Policy as a Defense of White Nationhood JUAN F. PEREA* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE FRAMERS' WISH FOR A WHITE AMERICA ................... 3 II. THE CYCLES OF MEXICAN EXPULSION ........................ 5 III. DEPORTATION AND MASS EXPULSION: SOCIAL CONTROL TO KEEP AMERICA WH ITE .................... ....................... 11 President Trump has declared war on undocumented immigrants. Attempting to motivate his voters before the 2018 mid-term elections, President Trump sought to sow fear by escalating his anti-immigrant rhetoric.1 Trump labeled a caravan of Central American refugees seeking asylum as an "invasion" and a "crisis" that demanded, in his view, the use of military troops to defend the U.S. border with Mexico. 2 When the caravan arrived, the border patrol used tear gas on the refugees, including mothers with infant children.3 Trump also referred to undocumented immigrants as criminals, rapists, and gang members who pose a direct threat to the welfare of "law-abiding" people.4 Despite the imagery of invasion, crisis, and crime disseminated by President Trump, undocumented immigrants pose no such threats. -

LITERATURE REVIEW Examples

Here are some examples of literature reviews to help you grasp what I mean by synthesis of materials: http://sociology2community.files.wordpress.com/2008/11/example_litreview_emsc_lit.pdf http://sociology2community.files.wordpress.com/2008/11/childhealth_litrev.pdf Here is an example of a recent literature review I did for a journal article. LITERATURE REVIEW Nativism and Racism – Separate Phenomena Most scholars want to define nativism and racism as two distinct phenomena. On one hand, nativism is an ideological belief based on nationalist sentiment and separates “natives” from “foreigners” (Galindo and Vigil 2006). Higham (1955:4) defines nativism as an: “intense opposition to an internal minority on the ground of its foreign (i.e., ‘un-American’) connections…a zeal to destroy the enemies of a distinctively American way of life.” Also, Higham (1999:384) states that “nativism always divided insiders, who belonged to the nation, from outsiders, who were in it but not of it.” Nativism frequently becomes imbedded in social structures, shaping the treatment of foreigners within institutions, deciding “who counts as an American” (Galindo and Vigil 2006:422; Higham 1955; Knobel 1996). Nativism rises up during times of national crisis through anti-immigrant sentiment that emphasizes fears that foreigners are either threatening or taking over culturally, politically, or economically. These national calamities usually include economic downturns, wars (or terrorist attacks), or sudden increases in visibility due to the size or concentration of immigrant populations (Galindo and Vigil 2006; Higham 1955; Perea 1997; Portes and Rumbaut 2006; Sánchez 1997). Systematic actions influenced by nativism have included restrictive immigration policies and laws, increases in riots and hate crimes, and the rise of nativist organizations. -

The God Who Hears Prayer Inside Illinoisillinois Members Focus News on the Web in This Issue / Telling the Stories of What God Is Doing in the Lives of His People

JUNE/JULY 2020 THE GOD WHO HEARS PRAYER ILLINOIS MEMBERS ILLINOIS FOCUS INSIDE NEWS ON THE WEB IN THIS ISSUE / TELLING THE STORIES OF WHAT GOD IS DOING IN THE LIVES OF HIS PEOPLE FEATURES Visit lakeunionherald.org for 14 Illinois — Camp Akita more on these and other stories By Mary Claire Smith Wisconsin’s Adventist Community Service volunteers made much needed 16 tie- and elastic-strapped masks for facilities and individuals. They were Download the Herald to your Indiana — Timber Ridge Camp asked to make masks for a 300-bed facility By Charlie Thompson in Pennsylvania which had experienced 38 mobile device! Just launch your PERSPECTIVES deaths due to the virus. camera and point it at the QR code. President's Perspective 4 18 (Older model devices may require Lest We Forget 8 downloading a third party app.) Conversations with God 9 Michigan — Camp Au Sable On Tuesday, May 5, the Michigan So, how’s your world? I remember Conference Executive Committee voted Conexiones 11 By Bailey Gallant my grandparents telling me about the to close the Adventist Book Centers One Voice 42 in Lansing, Berrien Springs and Cicero old days in North Dakota. One day I 20 (Indiana). They are exploring options to was walking through the Watford city EVANGELISM continue supplying printed material in cemetery where my great-grandfather Wisconsin — Camp Wakonda more efficient ways. Sharing Our Hope 10 Melchior was buried. I noticed that By Kristin Zeismer Telling God’s Stories 12 Follow us at lakeunionherald so many of the tombstones were Partnership With God 41 As part of its Everyone Counts, dated 1918, the year of the Spanish flu 22 Everyone Matters theme for the year, pandemic. -

Lake Union Herald for 1969

4,140m.e, LJELJ 1.2=H ors\ri I n) May 27, 1469 Volume LXI Number 21 ti Vol. LX1, No. 21 May 27, 1969 GORDON 0. ENGEN, Editor JOCELYN FAY, Assistant Editor S May 30, the closing date for `BUT SEEK YE MRS. MARIAN MENDEL, Circulation Services ,qthe Faith for Today Valentine offering, approaches, the story of EDITORIAL COMMITTEE: F. W. Wernick, Chairman; W. F. FIRST THE KINGDOM Miller, Vice-Chairman; Gordon Engen, Secretary. eight-year-old Reggie Swensen re- CORRESPONDENTS: Eston Allen, Illinois; M. D. Oswald, Indiana; Xavier B':tler, Lake Region; Ernest Wendth, opens. A second-grader at the Michigan; Melvin Rosen, Jr., Wisconsin; Everett Butler, OF GOD, AND HIS Hinsdale Sanitarium and Hospital; Horace Show, Andrews Andrews elementary school in Ber- University. NOTICE TO CONTRIBUTORS: All articles, pictures, obitu- rien Springs, Michigan, Reggie gave aries, and classified ads must be channeled through your local conference correspondent. Copy mailed directly to $50 of the $105 raised by his room. RIGHTEOUSNESS; the HERALD will be returned to the conference involved. MANUSCRIPTS for publication should reach the Lake For a long time Reggie had saved Union Conference office by Thursday, 9 a.m., twelve days before the dote of issue. The editorial staff reserves the to buy a five-speed bicycle. Even AND ALL THESE right to withhold or condense copy depending upon space available. after his parents pointed out the ADDRESS CHANGES should be addressed Circulation De- length of time it had taken him to partment, Lake Union Herald, Box C, Berrien Springs, THINGS SHALL BE Mich. -

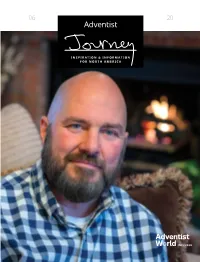

Adventist Health and Healing Adventist Journey

06 20 INSPIRATION & INFORMATION FOR NORTH AMERICA INCLUDED Share the story of Adventist Health and Healing Adventist Journey AdventHealth is sharing the legacy and stories of the Seventh-day Adventist Contents 04 Feature 11 NAD Newsbriefs Loving People—Beyond Church with our 80,000 team members the Dentist’s Chair through a series of inspirational videos and other resources. 08 NAD Update 13 Perspective Breath of Life Revival Leads to On the Same Team More Than 15,000 Baptisms My Journey As I reflect on my journey, I recognize that God doesn’t promise that it’s going to be an easy path or an enjoyable path. Sometimes there are struggles and trials and hardships. But Join us in the journey. looking back, I realize that each one of those has strengthened Watch the videos and learn more at: my faith, strengthened my resolve, to trust in Him more and AdventHealth.com/adventisthealthcare more every day. Visit vimeo.com/nadadventist/ajrandygriffin for more of Griffin’s story. GETTING TO KNOW MEMBER SERIES ADVENTISTS | TEAM MEMBER SERIE TEA M GETTING TO KNOW ADVENTISTS | TEAM MEMBER SERIES S GETTING TO KNOW ADVENTISTS | Adventist Education RANDY GRIFFIN, Adventist Health Care Worldwide INTRODUCTION Getting to Know Adventists The Seventh-day Adventist Church operates the largest Protestant education system in the world, with more than 8,000 schools in more than 100 countries. With the belief that education is more than just intellectual growth, Adventist education Cicero, Indiana, GETTING TO KNOW ADVENTISTS | TEAM MEMBER SERIES INTRODUCTION also focuses on physical, social, and spiritual Driven by the desire to bring restoration to a broken development. -

Re-Indigenizing Spaces: How Mapping Racial Violence Shows the Interconnections Between

“Re-Indigenizing Spaces: How Mapping Racial Violence Shows the Interconnections Between Settler Colonialism and Gentrification” By Jocelyn Lopez Senior Honors Thesis for the Ethnic Studies Department College of Letters and Sciences Of the University of California, Berkeley Thesis Advisor: Professor Beth Piatote Spring 2020 Lopez, 2 Introduction Where does one begin when searching for the beginning of the city of Inglewood? Siri, where does the history of Inglewood, CA begin? Siri takes me straight to the City History section of the City of Inglewood’s website page. Their website states that Inglewood’s history begins in the Adobe Centinela, the proclaimed “first home” of the Rancho Aguaje de la Centinela which housed Ignacio Machado, the Spanish owner of the rancho who was deeded the adobe in 1844. Before Ignacio, it is said that the Adobe Centinela served as a headquarters for Spanish soldiers who’d protect the cattle and springs. But from whom? Bandits or squatters are usually the go to answers. If you read further into the City History section, Inglewood only recognizes its Spanish and Mexican past. But where is the Indigenous Tongva-Gabrielino history of Inglewood? I have lived in Inglewood all of my life. I was born at Centinela Hospital Medical Center on Hardy Street in 1997. My entire K-12 education came from schools under the Inglewood Unified School District. While I attend UC Berkeley, my family still lives in Inglewood in the same house we’ve lived in for the last 23 years. Growing up in Inglewood, in a low income, immigrant family I witnessed things in my neighborhood that not everyone gets to see. -

Competing for Capitalized Power in Locally Controlled Immigration Enforcement

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2017 The punishment marketplace: Competing for capitalized power in locally controlled immigration enforcement Daniel L. Stageman CUNY John Jay College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/159 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Article Theoretical Criminology 1–20 The punishment © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav market place: Compet ing for DOI: 10.1177/1362480617733729 capitalized power in locally journals.sagepub.com/home/tcr controlled immigration enforcement Daniel L St agem an John Jay College of Criminal Justice, USA A bst r act Neoliberal economics play a significant role in U S so ci al o r ganizat io n, imposing market logics on public services and driving the cultural valo r izat io n o f fr ee mar ket i deo lo gy. The neoliberal ‘project of inequalit y’ is upheld by an aut horitarian system of punishment built around t he social control of the under class—amo ng t hem unauthorized immigr ants. This work lays out t he theory of t he punishment marketplace: a conceptualization of how US systems of punishment both enable the neoliberal project of inequality, and are t hemselves subject to market colonizat io n. The t heor y descr ibes t he r escaling of feder al aut hor it y t o local centers of political power. -

![Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living [Review] / Wilson, Brian C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2004/dr-john-harvey-kellogg-and-the-religion-of-biologic-living-review-wilson-brian-c-2242004.webp)

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living [Review] / Wilson, Brian C

244 SEMINARY STUDIES 53 (SPRING 2015) on words not known interrupts the reading experience more substantially than moving one’s eyes quickly to the apparatus and back. Third, annotating one’s Hebrew Bible with pen or pencil allows for a more efficient ownership of the Biblical Hebrew language and the Hebrew Bible. Fourth, for Hebrew professors and language instructors the BHS Reader’s Edition allows for new ways of testing the skills of Hebrew students. Final examinations can be set up in which no dictionary or grammar is allowed. In case of too much information being given in the apparatus, information can be removed easily in the process of text-copying. In conclusion, the BHS Reader’s Edition is a must for everybody who studied Hebrew for a purpose other than spoiling costly time and mental energies. The challenges that come with this edition can be overcome after some praxis. The BHS Reader’s Edition is able to break the curse that hangs over every Hebrew course into a blessing: Learning Hebrew for the purpose of actually reading Hebrew and studying the Hebrew Bible in a more substantial way. Andrews University OLIVER GLANZ Wilson, Brian C. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living. Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana Univ. Press, 2014. 258 pp. Hardcover, $35.00. Brian C. Wilson is professor of American religious history and former chair of the Department of Comparative Religion at Western Michigan University. Prior to the volume reviewed here, Wilson has authored and edited several books, including: Christianity (Prentice Hall & Routledge, 1999), Reappraising Durkheim for the Study and Teaching of Religion Today (Brill, 2001), and Yankees in Michigan (Michigan State University, 2008).