Identification of Seventh-Day Adventist Health Core Convictions : Alignment with Current Healthcare Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spiritual Disciplines of Early Adventists Heather Ripley Crews George Fox University, [email protected]

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2016 Spiritual Disciplines of Early Adventists Heather Ripley Crews George Fox University, [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Crews, Heather Ripley, "Spiritual Disciplines of Early Adventists" (2016). Doctor of Ministry. Paper 139. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/139 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY SPIRITUAL DISCIPLINES OF EARLY ADVENTISTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GEORGE FOX EVANGELICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY LEADERSHIP AND SPIRITUAL FORMATION BY HEATHER RIPLEY CREWS PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Heather Ripley Crews All rights reserved. ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the Biblical spirituality of the early Adventist Church in order to apply the spiritual principles learned to the contemporary church. Though it is God who changes people, the early Adventists employed specific spiritual practices to place themselves in His presence. Research revealed five main spiritual disciplines that shaped the Advent leaders and by extension the church. The first is Bible study: placing the Holy Scriptures as the foundation for all beliefs. The second is prayer: communication and communion with God. -

INSIDE LOOK Christian Bioethics WINTER 2021

center for INSIDE LOOK christian bioethics WINTER 2021 “A Scholarly Conversation” Podcast Series Race, Religion, and Reproduction Listen to the latest episode of the Center’s podcast featuring Graduate Assistant Hazel Ezeribe Janice De-Whyte, PhD interviewing Dr. Janice De-Whyte who is a pastor, Assistant Professor, Theology Studies biblical scholar, and professor at the LLU School of LLU School of Religion Religion. Dr. De-Whyte discusses the intersection of gender, healthcare, and religion by examining the cultural significance of childbearing in the Old Testament. The conversation also touches on the impact of this intersection on black women in particular and how we might address these issues. Hazel Ezeribe, BS, Listen on Apple Podcasts MA class of 2021, MD class of 2022 or on Spotify. Graduate Assistant, LLU Center for Christian Bioethics An Inside Look at the Adventist Bioethics Consortium by Nicolas Belliard, Graduate Assistant While many of the supporters of the Center for The annual meetings of the Adventist Bioethics Christian Bioethics are actively involved in the Consortium have been hosted by Adventist Adventist Bioethics Consortium (ABC), there are healthcare systems in North America. The some who may not be aware of the purpose or role of Consortium has grown to include several other the ABC. Even for readers who are aware of what the institutions including Adventist HealthCare Ltd. ABC does, there may be an unfamiliarity of when the (Australia), Universidad Peruana Unión, Andrews Consortium started and what its history has been. University, the North American Division of Seventh- This editorial is intended to provide information day Adventists, and the Pacific Union Conference of about the Adventist Bioethics Consortium. -

The God Who Hears Prayer Inside Illinoisillinois Members Focus News on the Web in This Issue / Telling the Stories of What God Is Doing in the Lives of His People

JUNE/JULY 2020 THE GOD WHO HEARS PRAYER ILLINOIS MEMBERS ILLINOIS FOCUS INSIDE NEWS ON THE WEB IN THIS ISSUE / TELLING THE STORIES OF WHAT GOD IS DOING IN THE LIVES OF HIS PEOPLE FEATURES Visit lakeunionherald.org for 14 Illinois — Camp Akita more on these and other stories By Mary Claire Smith Wisconsin’s Adventist Community Service volunteers made much needed 16 tie- and elastic-strapped masks for facilities and individuals. They were Download the Herald to your Indiana — Timber Ridge Camp asked to make masks for a 300-bed facility By Charlie Thompson in Pennsylvania which had experienced 38 mobile device! Just launch your PERSPECTIVES deaths due to the virus. camera and point it at the QR code. President's Perspective 4 18 (Older model devices may require Lest We Forget 8 downloading a third party app.) Conversations with God 9 Michigan — Camp Au Sable On Tuesday, May 5, the Michigan So, how’s your world? I remember Conference Executive Committee voted Conexiones 11 By Bailey Gallant my grandparents telling me about the to close the Adventist Book Centers One Voice 42 in Lansing, Berrien Springs and Cicero old days in North Dakota. One day I 20 (Indiana). They are exploring options to was walking through the Watford city EVANGELISM continue supplying printed material in cemetery where my great-grandfather Wisconsin — Camp Wakonda more efficient ways. Sharing Our Hope 10 Melchior was buried. I noticed that By Kristin Zeismer Telling God’s Stories 12 Follow us at lakeunionherald so many of the tombstones were Partnership With God 41 As part of its Everyone Counts, dated 1918, the year of the Spanish flu 22 Everyone Matters theme for the year, pandemic. -

Lake Union Herald for 1969

4,140m.e, LJELJ 1.2=H ors\ri I n) May 27, 1469 Volume LXI Number 21 ti Vol. LX1, No. 21 May 27, 1969 GORDON 0. ENGEN, Editor JOCELYN FAY, Assistant Editor S May 30, the closing date for `BUT SEEK YE MRS. MARIAN MENDEL, Circulation Services ,qthe Faith for Today Valentine offering, approaches, the story of EDITORIAL COMMITTEE: F. W. Wernick, Chairman; W. F. FIRST THE KINGDOM Miller, Vice-Chairman; Gordon Engen, Secretary. eight-year-old Reggie Swensen re- CORRESPONDENTS: Eston Allen, Illinois; M. D. Oswald, Indiana; Xavier B':tler, Lake Region; Ernest Wendth, opens. A second-grader at the Michigan; Melvin Rosen, Jr., Wisconsin; Everett Butler, OF GOD, AND HIS Hinsdale Sanitarium and Hospital; Horace Show, Andrews Andrews elementary school in Ber- University. NOTICE TO CONTRIBUTORS: All articles, pictures, obitu- rien Springs, Michigan, Reggie gave aries, and classified ads must be channeled through your local conference correspondent. Copy mailed directly to $50 of the $105 raised by his room. RIGHTEOUSNESS; the HERALD will be returned to the conference involved. MANUSCRIPTS for publication should reach the Lake For a long time Reggie had saved Union Conference office by Thursday, 9 a.m., twelve days before the dote of issue. The editorial staff reserves the to buy a five-speed bicycle. Even AND ALL THESE right to withhold or condense copy depending upon space available. after his parents pointed out the ADDRESS CHANGES should be addressed Circulation De- length of time it had taken him to partment, Lake Union Herald, Box C, Berrien Springs, THINGS SHALL BE Mich. -

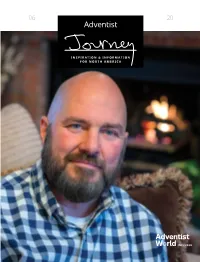

Adventist Health and Healing Adventist Journey

06 20 INSPIRATION & INFORMATION FOR NORTH AMERICA INCLUDED Share the story of Adventist Health and Healing Adventist Journey AdventHealth is sharing the legacy and stories of the Seventh-day Adventist Contents 04 Feature 11 NAD Newsbriefs Loving People—Beyond Church with our 80,000 team members the Dentist’s Chair through a series of inspirational videos and other resources. 08 NAD Update 13 Perspective Breath of Life Revival Leads to On the Same Team More Than 15,000 Baptisms My Journey As I reflect on my journey, I recognize that God doesn’t promise that it’s going to be an easy path or an enjoyable path. Sometimes there are struggles and trials and hardships. But Join us in the journey. looking back, I realize that each one of those has strengthened Watch the videos and learn more at: my faith, strengthened my resolve, to trust in Him more and AdventHealth.com/adventisthealthcare more every day. Visit vimeo.com/nadadventist/ajrandygriffin for more of Griffin’s story. GETTING TO KNOW MEMBER SERIES ADVENTISTS | TEAM MEMBER SERIE TEA M GETTING TO KNOW ADVENTISTS | TEAM MEMBER SERIES S GETTING TO KNOW ADVENTISTS | Adventist Education RANDY GRIFFIN, Adventist Health Care Worldwide INTRODUCTION Getting to Know Adventists The Seventh-day Adventist Church operates the largest Protestant education system in the world, with more than 8,000 schools in more than 100 countries. With the belief that education is more than just intellectual growth, Adventist education Cicero, Indiana, GETTING TO KNOW ADVENTISTS | TEAM MEMBER SERIES INTRODUCTION also focuses on physical, social, and spiritual Driven by the desire to bring restoration to a broken development. -

State-Of-The-University-Web-Version

WAU Board Chair Dave Weigley and WAU President Weymouth Spence at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. WASHINGTON ADVENTIST UNIVERSITY 2 OUR VISION THANK YOU For your continued support! MESSAGE FROM WAU BOARD CHAIRMAN DAVE WEIGLEY Blessed to be a Blessing In 1904 Seventh-day Adventist Church leaders established service days in the community. a training college in Takoma Park, Md., just outside We continue to promote academic excellence, seek the United States capital, to prepare young men and internships and secure opportunities that will prepare women for service to God and the community. At the first students to land a job and achieve success in today’s commencement, held May 22, 1915, five students received competitive work environment. Bachelor of Arts degrees. We continue to seek partnerships —locally and abroad— Last May that school, now Washington Adventist that expand and enhance our ability to grow the University (WAU), celebrated its 100th commencement university, revitalize our campus with new facilities and with 289 graduates who walked under the famed Gateway make Adventist education accessible on a global scale. to Service arch. They joined the ranks of some 12,000 alumni who have matriculated at our Columbia Union As we continue to deliver and pursue excellence at WAU, Conference’s flagship university and accepted the call to a my prayer is that we will also continue to “be blessed … to life of service. What a blessing! be a blessing” (see Gen. 12:2). During a century of ministry, WAU has experienced Courage, growth, change and many, many blessings from the Lord. -

![Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living [Review] / Wilson, Brian C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2004/dr-john-harvey-kellogg-and-the-religion-of-biologic-living-review-wilson-brian-c-2242004.webp)

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living [Review] / Wilson, Brian C

244 SEMINARY STUDIES 53 (SPRING 2015) on words not known interrupts the reading experience more substantially than moving one’s eyes quickly to the apparatus and back. Third, annotating one’s Hebrew Bible with pen or pencil allows for a more efficient ownership of the Biblical Hebrew language and the Hebrew Bible. Fourth, for Hebrew professors and language instructors the BHS Reader’s Edition allows for new ways of testing the skills of Hebrew students. Final examinations can be set up in which no dictionary or grammar is allowed. In case of too much information being given in the apparatus, information can be removed easily in the process of text-copying. In conclusion, the BHS Reader’s Edition is a must for everybody who studied Hebrew for a purpose other than spoiling costly time and mental energies. The challenges that come with this edition can be overcome after some praxis. The BHS Reader’s Edition is able to break the curse that hangs over every Hebrew course into a blessing: Learning Hebrew for the purpose of actually reading Hebrew and studying the Hebrew Bible in a more substantial way. Andrews University OLIVER GLANZ Wilson, Brian C. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living. Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana Univ. Press, 2014. 258 pp. Hardcover, $35.00. Brian C. Wilson is professor of American religious history and former chair of the Department of Comparative Religion at Western Michigan University. Prior to the volume reviewed here, Wilson has authored and edited several books, including: Christianity (Prentice Hall & Routledge, 1999), Reappraising Durkheim for the Study and Teaching of Religion Today (Brill, 2001), and Yankees in Michigan (Michigan State University, 2008). -

CORNFLAKES, GOD, and CIRCUMCISION: JOHN HARVEY KELLOGG and TRANSATLANTIC HEALTH REFORM by AUSTIN ELI LOIGNON DISSERTATION Submi

CORNFLAKES, GOD, AND CIRCUMCISION: JOHN HARVEY KELLOGG AND TRANSATLANTIC HEALTH REFORM by AUSTIN ELI LOIGNON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May, 2019 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Steven G. Reinhardt, Supervising Professor Kathryne E. Beebe Robert B. Fairbanks Copyright © by Austin Eli Loignon 2019 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Cornflakes, God, and Circumcision: John Harvey Kellogg and Transatlantic Health Reform Austin Eli Loignon, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2019 Supervising Professor: Steven G. Reinhardt The health reform movements of the nineteenth and early twentieth century impacted American and European societies in profound ways. These reforms, while usually represented in a national context, existed within a transatlantic framework that facilitated a multitude of exchanges and transfers. John Harvey Kellogg—surgeon, health reformer, and inventor of cornflakes— developed a transatlantic network of health reformers, medical practitioners, and scientists to improve his own reforms and establish new ones. Through intercultural transfer Kellogg borrowed, modified, and implemented European health reform practices at his Battle Creek Sanitarium in the United States. These transfers facilitated developments in reform movements such as vegetarianism, light therapy, sex, and eugenics. While health reform movements were a product of the modern world in which science and rationality were given preference, Kellogg infused his religious, Seventh-day Adventist beliefs into the reforms he practiced. In some cases health reform movements were previously semi-religious in nature and Kellogg merely accentuated an already present narrative of religious obligation for reform. These beliefs in salvific health reform centered around Kellogg’s desire to perfect the human body physically and spiritually in an attempt to make it fit for translation into heaven. -

CO 2869Book Redo

W.K. Kellogg Foundation “I’ll Invest My Money in People” A biographical sketch of the Founder of the Kellogg Company and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation “I’ll Invest My Money in People” Published by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation Battle Creek, Michigan Tenth Edition, February 2002 Revised and reprinted 2000,1998, 1993, 1991, 1990, 1989, 1987, 1984. First edition published 1979. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-063691 Printed in the United States of America Table of Contents Part 1 – W.K. Kellogg’s House Van Buren Street Residence 5 Part 2 – The Philanthropist “I’ll Invest My Money In People” 29 Beginnings 30 The Sanitarium Years 45 The Executive 48 Success and Tragedy 51 The Shy Benefactor 63 The W.K. Kellogg Foundation 70 A home is not a mere transient shelter. Its essence lies in its permanence, in its capacity for accretion and solidification, in its quality of representing, in all its details, the personalities of the people who live in it. H.L. Mencken, 1929 Part 1 W.K. Kellogg’s House Van Buren Street Residence W.K. Kellogg. The man’s name, spoken or written, almost a half-century after his death, is associated with entrepreneurship, creativity, vision, and humanitarianism. Those are big words. However appropriate they may be, 5 they probably would have been shunned by Mr. Kellogg—the developer of a worldwide cereal industry and an international foundation that is dedicated to helping people to solve societal problems. He shied from any hint of praise for himself. With a candor that matched his devotion to action and outcomes, he was known to turn aside compliments, flattery, or acclaim. -

Your Guide to Top Care

2019 EDITION Exclusive Rankingskings How Hospitalss YOUR Are Battling thehe GUIDE Opioid Epidemicemic TO TOP Surgery Ahead?head? CARE Ask These Questionsestions Why STRENGTH TRAINING Really Matterss PLUS: America’s Healthiest Communities It’s Time to Plan Ahead Every 40 seconds, someone in America has a stroke or a heart attack.ck. Chances are it could be you or someone you love. That’s why it’s crucial to researchh the best options for receiving heart and stroke care before thee ttimeime comes when you need it. Each year, the American Heart Association recognizes hospitals that demonstrate a high commitment to following guidelines that improve patient outcomes. Read more about the award categories and locate a participating hospital near you. From 2005 to 2015 Currently, more More than 7 million the annual death than 2,500 hospitals people have been rate attributable to participate in at least treated through our coronary heart one American Heart hospital-based disease declined 34.4 Association quality quality initiatives percent. The number initiative module. since the first of deaths declined Many participate in one was launched 17.7 percent. two or more. in 2000. ISTOCK © 2018 American Heart Association SPONSORED CONTENT Key to the Awards Gold Achievement A A A A Silver Achievement C C C C These hospitals are recognized for two or more consecutive These hospitals are recognized for one calendar year of calendar years of 85% or higher adherence on all 85% or higher adherence on all achievement measures achievement measures applicable -

VIRTUAL CONFERENCE May 3-5, 2021 ETHICS for the MINISTRY of HEALING a Conference for Leaders in Adventist Healthcare Designed To: 1

Program VIRTUAL CONFERENCE May 3-5, 2021 ETHICS FOR THE MINISTRY OF HEALING A conference for leaders in Adventist healthcare designed to: 1. Address current issues in clinical ethics CLICK HERE 2. Foster a vibrant network of leaders in bioethics to join 3. Consider theological bases for ethics in Adventist health systems Zoom Meeting 4. Clarify ethical understanding between the church and its health systems Who should attend? Virtual conference format: ✓ Ethics committee members ✓ No registration fee! ✓ Healthcare executives ✓ No registration required ✓ Healthcare professionals ✓ Zoom Meeting ID: 965 7629 9557 ✓ Hospital chaplains ✓ Each day has up to 4 hours of live sessions ✓ Church leaders ✓ Ample opportunity for discussion ✓ Ethics professors ✓ Network via zoom chat ✓ Healthcare attorneys ✓ Each session to be recorded and will be available ✓ Anyone interested in healthcare ethics on adventistbioethics.org after the conference Welcome Message Events of this past year have provided dramatic evidence for the value of a faithful learning collaborative devoted to ethics in health care. At this fifth conference of the Adventist Bioethics Consortium, we will have rich opportunities to learn from each other about advancing ethical responsibility in the organizations we serve. It is an honor to welcome you to the conference and thank you for choosing to participate. Gerald R. Winslow, PhD Director, LLU Center for Christian Bioethics Coordinated by Loma Linda University Center for Christian Bioethics [email protected] 909.558.4956 www.adventistbioethics.org -

Columbia Union Visitor for 2008

Contents june 2008 In Every Issue 3 | Editorial 4 | Newsline 8 | Potluck Newsletters 10 25 Allegheny East 27 Allegheny West News & Features 29 Chesapeake 31 Columbia Union College 33 Highland View Academy 10 | Remembering the Vision 35 Mountain View Some 3,500 people gathered recently in Ohio to commemorate 37 Mt. Vernon Academy the 150th anniversary of the vision that led Adventist co-founder 39 New Jersey Ellen G. White to write The Great Controversy. We take you there through photos and quotes. 41 Ohio 43 Pennsylvania 14 | What Does The Great 45 Potomac 47 Shenandoah Valley Controversy Mean to You? Academy Have you read or recently re-read Ellen White’s prolific work 48 Takoma Academy The Great Controversy? Why is it so significant to our church and future? As you contemplate its meaning in your life, read what attendees at last month’s commemorative gathering had to say. 51 | Bulletin Board 16 | 10 Tip-Top Students 56 | Last Words Brian Jones This graduation season, we pause to recognize the Columbia Union Conference’s On the Web Caring Heart Award recipi - Stay connected to your church ents. On top of studying, family. Stop by regularly to enjoy working, and engaging in current news, videos, podcasts, photo blogs, and more. extracurricular sports, music, or spiritual activities, these columbiaunion.org exemplary students demon - strate personal commitment to About the Cover: These service and witnessing. Meet this year’s awardees from the Columbia Union presidents Columbia Union’s 10 academies and find out why they are tops! gathered in Kettering, Ohio, last month at Ridgeleigh Terrace, the one-time mansion of inventor Charles F.