34.Pdf (322.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anzac Day 2015

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2014-15 UPDATED 16 APRIL 2015 Anzac Day 2015 David Watt Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section This ‘Anzac Day Kit’ has been compiled over a number of years by various staff members of the Parliamentary Library, and is updated annually. In particular the Library would like to acknowledge the work of John Moremon and Laura Rayner, both of whom contributed significantly to the original text and structure of the Kit. Nathan Church and Stephen Fallon contributed to the 2015 edition of this publication. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 What is this kit? .................................................................................................. 4 Section 1: Speeches ..................................................................................... 4 Previous Anzac Day speeches ............................................................................. 4 90th anniversary of the Anzac landings—25 April 2005 .................................... 4 Tomb of the Unknown Soldier............................................................................ 5 Ataturk’s words of comfort ................................................................................ 5 Section 2: The relevance of Anzac ................................................................ 5 Anzac—legal protection ..................................................................................... 5 The history of Anzac Day ................................................................................... -

Kelson Nor Mckernan

Vol. 5 No. 9 November 1995 $5.00 Fighting Memories Jack Waterford on strife at the Memorial Ken Inglis on rival shrines Great Escapes: Rachel Griffiths in London, Chris McGillion in America and Juliette Hughes in Canberra and the bush Volume 5 Number 9 EURE:-KA SJRE:i:T November 1995 A magazine of public affairs, the arts and th eology CoNTENTS 4 30 COMMENT POETRY Seven Sketches by Maslyn Williams. 9 CAPITAL LETTER 32 BOOKS 10 Andrew Hamilton reviews three recent LETTERS books on Australian immigration; Keith Campbell considers The Oxford 12 Companion to Philosophy (p36); IN GOD WE BUST J.J.C. Smart examines The Moral Chris McGillion looks at the implosion Pwblem (p38); Juliette Hughes reviews of America from the inside. The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen Vol I and Hildegard of Bingen and 14 Gendered Theology in Ju dea-Christian END OF THE GEORGIAN ERA Tradition (p40); Michael McGirr talks Michael McGirr marks the passing of a to Hugh Lunn, (p42); Bruce Williams Melbourne institution. reviews A Companion to Theatre in Australia (p44); Max T eichrnann looks 15 at Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth COUNTERPOINT (p46); James Griffin reviews To Solitude The m edia's responsibility to society is Consigned: The Journal of William m easured by the code of ethics, says Smith O'BTien (p48). Paul Chadwick. 49 17 THEATRE ARCHIMEDES Geoffrey Milne takes a look at quick changes in W A. 18 WAR AT THE MEMORIAL 51 Ja ck Waterford exarnines the internal C lea r-fe Jl ed forest area. Ph oto FLASH IN THE PAN graph, above left, by Bill T homas ructions at the Australian War Memorial. -

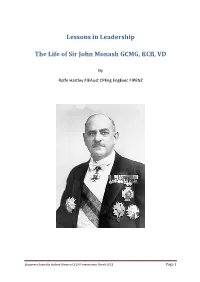

Lessons in Leadership the Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD

Lessons in Leadership The Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD By Rolfe Hartley FIEAust CPEng EngExec FIPENZ Engineers Australia Sydney Division CELM Presentation March 2013 Page 1 Introduction The man that I would like to talk about today was often referred to in his lifetime as ‘the greatest living Australian’. But today he is known to many Australians only as the man on the back of the $100 note. I am going to stick my neck out here and say that John Monash was arguably the greatest ever Australian. Engineer, lawyer, soldier and even pianist of concert standard, Monash was a true leader. As an engineer, he revolutionised construction in Australia by the introduction of reinforced concrete technology. He also revolutionised the generation of electricity. As a soldier, he is considered by many to have been the greatest commander of WWI, whose innovative tactics and careful planning shortened the war and saved thousands of lives. Monash was a complex man; a man from humble beginnings who overcame prejudice and opposition to achieve great things. In many ways, he was an outsider. He had failures, both in battle and in engineering, and he had weaknesses as a human being which almost put paid to his career. I believe that we can learn much about leadership by looking at John Monash and considering both the strengths and weaknesses that contributed to his greatness. Early Days John Monash was born in West Melbourne in 1865, the eldest of three children and only son of Louis and Bertha. His parents were Jews from Krotoshin in Prussia, an area that is in modern day Poland. -

Foxtel Programming in 2015 (PDF)

FOXTEL programming in 2015 GOGGLEBOX Season 1 The LifeStyle Channel Based on the U.K. smash hit, Gogglebox is a weekly observational series which captures the reactions of ordinary Australians as they watch the nightly news, argue over politics, cheer their favourite sporting teams and digest current affairs and documentaries. Twelve households will be chosen and then rigged with special, locked off cameras to capture every unpredictable moment. Gogglebox is like nothing else ever seen on Australian television and it’s set to hook audiences in a fun and entertaining way. The series has been commissioned jointly by Foxtel and Network Ten and will air first on The LifeStyle Channel followed by Channel Ten. DEADLINE GALLIPOLI Season 1 showcase Deadline Gallipoli explores the origin of the Gallipoli legend from the point of view of war correspondents Charles Bean, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, Phillip Schuler and Keith Murdoch, who lived through the campaign and bore witness to the extraordinary events that unfolded on the shores of Gallipoli in 1915. This compelling four hour miniseries captures the heartache and futility of war as seen through the eyes of the journalists who reported it. Joel Jackson stars as Bean, Hugh Dancy as Bartlett, Ewen Leslie as Murdoch, and Sam Worthington as Schuler. Charles Dance plays Hamilton, the Commander of the Gallipoli campaign, Bryan Brown plays General Bridges and John Bell plays Lord Kitchener. Deadline Gallipoli will be broadcast to coincide with the World War I Centenary commemorations. THE KETTERING INCIDENT Season 1 showcase Elizabeth Debicki, Matt Le Nevez, Anthony Phelan, Henry Nixon and Sacha Horler star in The Kettering Incident drama series. -

News Corporation 1 News Corporation

News Corporation 1 News Corporation News Corporation Type Public [1] [2] [3] [4] Traded as ASX: NWS ASX: NWSLV NASDAQ: NWS NASDAQ: NWSA Industry Media conglomerate [5] [6] Founded Adelaide, Australia (1979) Founder(s) Rupert Murdoch Headquarters 1211 Avenue of the Americas New York City, New York 10036 U.S Area served Worldwide Key people Rupert Murdoch (Chairman & CEO) Chase Carey (President & COO) Products Films, Television, Cable Programming, Satellite Television, Magazines, Newspapers, Books, Sporting Events, Websites [7] Revenue US$ 32.778 billion (2010) [7] Operating income US$ 3.703 billion (2010) [7] Net income US$ 2.539 billion (2010) [7] Total assets US$ 54.384 billion (2010) [7] Total equity US$ 25.113 billion (2010) [8] Employees 51,000 (2010) Subsidiaries List of acquisitions [9] Website www.newscorp.com News Corporation 2 News Corporation (NASDAQ: NWS [3], NASDAQ: NWSA [4], ASX: NWS [1], ASX: NWSLV [2]), often abbreviated to News Corp., is the world's third-largest media conglomerate (behind The Walt Disney Company and Time Warner) as of 2008, and the world's third largest in entertainment as of 2009.[10] [11] [12] [13] The company's Chairman & Chief Executive Officer is Rupert Murdoch. News Corporation is a publicly traded company listed on the NASDAQ, with secondary listings on the Australian Securities Exchange. Formerly incorporated in South Australia, the company was re-incorporated under Delaware General Corporation Law after a majority of shareholders approved the move on November 12, 2004. At present, News Corporation is headquartered at 1211 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Ave.), in New York City, in the newer 1960s-1970s corridor of the Rockefeller Center complex. -

Page | 1 Keepsakes: Australians and the Great War 26 November 2014

Keepsakes: Australians and the Great War 26 November 2014 – 19 July 2015 EXHIBITION CHECKLIST INTRODUCTORY AREA Fred Davison (1869–1942) Scrapbook 1913–1942 gelatin silver prints, medals and felt; 36 x 52 cm (open) Manuscripts Collection, nla.cat-vn1179442 Eden Photo Studios Portrait of a young soldier seated in a carved chair c. 1915 albumen print on Paris Panel; 25 x 17.5 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-vn6419940 Freeman & Co. Portrait of Major Alexander Hay c. 1915 sepia toned gelatin silver print on studio mount; 33 x 23.5 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an24213454 Tesla Studios Portrait of an Australian soldier c. 1915 gelatin silver print; 30 x 20 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an24613311 The Sears Studio Group portrait of graduating students from the University of Melbourne c. 1918 gelatin silver print on studio mount; 25 x 30 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an23218020 Portrait of Kenneth, Ernest, Clive and Alice Bailey c. 1918 sepia toned gelatin silver print on studio mount; 22.8 x 29.7 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an23235834 Thelma Duryea Portrait of George Edwin Yates c. 1919 gelatin silver print on studio mount; 27.5 x 17.5 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an10956957 Portrait of Gordon Coghill c. 1918 sepia toned gelatin silver print; 24.5 x 16 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-vn3638073 Page | 1 Australian soldiers in Egypt sitting on one of the corners of the base of the Great Pyramid of Cheops, World War 1, 1914–1918 c. 1916 sepia toned gelatin silver print on card mount; 12 x 10.5 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an24613179 Embroidered postcard featuring a crucifix 1916 silk on card; 14 x 9 cm Papers of Arthur Wesley Wheen, nla.ms-ms3656 James C. -

How Rupert Murdoch's Empire of Influence Remade The

HOW RUPERT MURDOCH’S EMPIRE OF INFLUENCE REMADE THE WORLD Part 1: Imperial Reach Murdoch And His Children Have Toppled Governments On Two Continents And Destabilized The Most Important Democracy On Earth. What Do They Want? By Jonathan Mahler And Jim Rutenberg 3rd April 2019 1. ‘I LOVE ALL OF MY CHILDREN’ Rupert Murdoch was lying on the floor of his cabin, unable to move. It was January 2018, and Murdoch and his fourth wife, Jerry Hall, were spending the holidays cruising the Caribbean on his elder son Lachlan’s yacht. Lachlan had personally overseen the design of the 140-foot sloop — named Sarissa after a long and especially dangerous spear used by the armies of ancient Macedonia — ensuring that it would be suitable for family vacations while also remaining competitive in superyacht regattas. The cockpit could be transformed into a swimming pool. The ceiling in the children’s cabin became an illuminated facsimile of the nighttime sky, with separate switches for the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. A detachable board for practicing rock climbing, a passion of Lachlan’s, could be set up on the deck. But it was not the easiest environment for an 86-year-old man to negotiate. Murdoch tripped on his way to the bathroom in the middle of the night. Murdoch had fallen a couple of other times in recent years, once on the stairs while exiting a stage, another time on a carpet in a San Francisco hotel. The family prevented word from getting out on both occasions, but the incidents were concerning. This one seemed far more serious. -

'Murdoch Press' and the 1939 Australian Herald

Museum & Society, 11(3) 219 Arcadian modernism and national identity: The ‘Murdoch press’ and the 1939 Australian Herald ‘Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art’ Janice Baker* Abstract The 1939 Australian ‘Herald’ Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art is said not only to have resonated ‘in the memories of those who saw it’ but to have formed ‘the experience even of many who did not’ (Chanin & Miller 2005: 1). Under the patronage of Sir Keith Murdoch, entrepreneur and managing director of the Melbourne ‘Herald’ newspaper, and curated by the Herald’s art critic Basil Burdett, the exhibition attracted large and enthusiastic audiences. Remaining in Australia for the duration of the War, the exhibition of over 200 European paintings and sculpture, received extensive promotion and coverage in the ‘Murdoch press’. Resonating with an Australian middle-class at a time of uncertainty about national identity, this essay explores the exhibition as an ‘Arcadian’ representation of the modern with which the population could identify. The exhibition aligned a desire to be associated with the modern with a restoration of the nation’s European heritage. In its restoration of this continuity, the Herald exhibition affected an antiquarianism that we can explore, drawing on Friedrich Nietzsche’s insights into the use of traditional history. Keywords: affect; cultural heritage; Herald exhibition; Murdoch press; museums The Australian bush legend and the ‘digger’ tradition both extol the Australian character as one of endurance, courage and mateship (White 1981: 127). Graeme Davison (2000: 11) observes that using this form of ‘heroic’ tradition to inspire Australian national identity represents a monumental formation of the past that is ‘the standard form of history in new nations’. -

Newsletter 1

What's on in History Compiled by Fiona Poulton Professional Historians Association (Victoria) Historically Speaking – Members’ Current Work History Week 2016 Tuesday 8 November, 16-23 October La Notte Restaurant, 140-146 Lygon St, Carlton This perennially popular event on the Historically Speaking calendar offers members an Discover the wonders of Victoria’s past this History Week! From fascinating walking tours and engaging discussions, to exhibitions and ‘history in opportunity to discuss achievements, issues, milestones and problems associated with the making’ events – there is something in store for everyone to enjoy. their work as historians. Join us to discover what projects your colleagues have been engaged in 2016 and share your own achievements. This History Week you can… » meet well-known lawyers, murderers, a slain police officer and robbery victims now at rest in Bell Street » explore the stories of early Victoria’s many wild colonial boys, including the St SAVE THE DATE – 4 December 2016 Kilda Gang, the Plenty Gang and the Kelly Gang » discuss the meaning and power of place in Australia’s historical narrative » commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Melbourne Olympics and step into the shoes of an Argus Newspaper sports journalist » be transported back to Marvellous Melbourne with one of Australia’s most influential historians » join makers from all of the Yarra Ranges to recreate a time when clothes were made to last » enjoy an online exhibition of stirrers with style and learn other stories of women leaders And much more! Visit http://historyweek.org.au/ for the full calendar of events. The University of Melbourne George W. -

Teacher's Kit GALLIPOLI.Pdf

GALLIPOLI SCHOOLSDAY PERFORMANCE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Date: Wednesday 13th August 2008 Venue: Sydney Theatre Pre-performance forum 10.30 am Lunch Break 11.15 am Performance commences: 12.15 pm Performance concludes: 3.15 pm We respectfully ask that you discuss theatre etiquette with your students prior to coming to the performance. Running Late? Please contact Sydney Theatre Company’s main switch on 9250 1700 and a message will be passed to Front of House. Booking Queries Please contact Marietta Hargreaves on 02 9250 1778 or [email protected] General Education Queries Please contact Helen Hristofski, Education Manager, on 02 9250 1726 or [email protected] Sydney Theatre Company’s GALLIPOLI Teacher’s Notes compiled by Elizabeth Surbey © 2008 1 Sydney Theatre Company presents the STC Actors Company in GALLIPOLI Written and Devised by Nigel Jamieson in association with the Cast Teacher's Resource Kit Written and compiled by Elizabeth Surbey Sydney Theatre Company’s GALLIPOLI Teacher’s Notes compiled by Elizabeth Surbey © 2008 2 Acknowledgements Sydney Theatre Company would like to thank the following for their invaluable material for these Teachers' Notes: Laura Scrivano (STC) Helen Hristofski (STC) Copyright Copyright protects this Teacher’s Resource Kit. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited. However, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. Front Image of Alec Campbell used by kind permission of the Campbell -

DAME ELISABETH JOY MURDOCH Ac Dbe 1909–2012

30 THE AUSTRALIAN ACADEMY OF THE HUMANITIES ANNUAL REPORT 2012–13 DAME ELISABETH JOY MURDOCH ac dbe 1909–2012 carefully, from the first page to the last, the signatures of all Fellows elected to the Academy since its foundation in 1969. She chuckled with pleasure as she deciphered the names, and paused to report some fact or anecdote about each Fellow – there were a great many of them – whom she remembered personally, before signing her own name on the final page with a firm and clear hand. She’d taken her daily swim that morning and was in good spirits. There was wine from the family vineyard on the lunch table which she urged us to enjoy, as she did herself. When the time for her siesta arrived she sent us off for a tour of the gardens with a cheerful wave. Dame Elisabeth was a great benefactress not only (of course) to the humanities but to any cause that she considered worthy of her attention. Asked a few years ago if the number of charities she supported was around a hundred, she replied with modest vagueness that ‘That would be rather conservative’ as an estimate. She was deeply committed throughout much of her life to the work of the Children’s Hospital, of which she was President photo: aah archive for twelve years, and of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and the Murdoch Institute for Research into ame Elisabeth Murdoch, legendary philanthropist and Birth Defects. She was a Life Governor of the Royal Dfriend to the humanities, died at her home outside Women’s Hospital, a member of the Deafness Foundation Melbourne on 5 December 2012 at the age of 103. -

![LACHLAN MURDOCH SPEECH[1]Jc Edit-4-2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8241/lachlan-murdoch-speech-1-jc-edit-4-2-2558241.webp)

LACHLAN MURDOCH SPEECH[1]Jc Edit-4-2

1 SPEECH DELIVERED BY LACHLAN MURDOCH TO THE MELBOURNE PRESS CLUB MEDIA HALL OF FAME DECEMBER 6, 2012 My father was honoured to be invited to speak to you about his father, and I am equally honoured to take his place to speak to you about my grandfather. A man who I feel I Know intimately but whom I never met. I wish I had met Keith Murdoch. But he died, long before I was born. He died on October 4, 1952. He was just sixty-six. My grandfather was a journalist. That was all he wanted to be from when he was a very young boy. That was despite the fact that my grandfather was painfully shy and had a serious and often debilitating stammer. So serious that when he went to the railway station to buy a ticKet he had to give the man who sold the ticKets a hand written note!! Keith Murdoch’s father, the very Scottish and the very Reverend PatricK Murdoch wanted Keith to go to university but the 19 year old had three qualities that would sticK with him through his life… Determination; Persistence; and great Perseverance. So despite his father pushing him to follow a different path and after putting in a lot of hard worK he got a job at The Age. Another Scotsman, David Syme, who is also honoured here tonight and who saved The Age from banKruptcy was so impressed by the young Keith Murdoch’s shorthand that he offered him a casual job as the Malvern district correspondent – at the grand freelancer’s rate of a penny-halfpenny a line.