Super Who? Super You! Week

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had. -

Drawing Stories: Developing a Range of Illustration Styles to Enhance Graphic Storytelling by Tyler Brown

Drawing Stories: Developing a Range of Illustration Styles to Enhance Graphic Storytelling by Tyler Brown A final project submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Carolina State University College of Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Art + Design Animation/New Media Concentration Raleigh, North Carolina July 2015 Marc Russo, Committee Chair Assistant Professor of Art and Design Tania Allen, Committee Member Assistant Professor of Art and Design Patrick FitzGerald, Committee Member Associate Professor of Art and Design Acknowledgements I would like to first thank my committee, Professors Marc Russo, Pat FitzGerald, and Tania Allen for all of their help and counsel throughout this project, as well as Mike Bissinger for serving as a Technical Advisor and Traci Temple for guiding me through the research class. Another big thank you goes out to all the other instructors, classmates, and friends that I’ve learned so much from during my time here at NC State. I also want to thank my family for all of their support over the past few years, Susan my ever-patient wife, my parents, the in-laws, and all the rest! Finally, I’d like to dedicate this project to my grandmother, Judy Brown, who passed away during my time here. She was the most wonderful woman, my greatest confidant, and a huge supporter of my artwork and continuing education. It was with her encouragement that I was able to summon the strength to continue and finish this program. Thanks ya’ll! - (read with a smile and a yankee tease) Tyler Brown, -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

![Doc Savage: #000A - "The Doc Savage Authors" Archived at [.Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3891/doc-savage-000a-the-doc-savage-authors-archived-at-pdf-2413891.webp)

Doc Savage: #000A - "The Doc Savage Authors" Archived at [.Pdf]

Doc Savage: #000A - "the Doc Savage Authors" archived at http://www.stealthskater.com/DocSavage/DS000_Authors.doc [.pdf] to read more Doc Savage novels, go to http://www.stealthskater.com/DocSavage.htm Background and History of the Publishing of "Doc Savage" last updated December 10, 2010 Introduction Authors the Bantam Book paperback series Bantam Cover Artists some Doc Savage-related Websites the history of "Kenneth Robeson" (the "author" of the Doc Savage series) an interview with contemporary "Doc Savage" author Will Murray the "Maturing" of the Doc Savage character a Summary of the 3 Decades of Lester Dent's writings "Why 'Kenneth Robeson' Doesn't Write Anymore" the 1975 "Doc Savage" movie Doc Savage: Arch Enemy of Evil (history and interviews) Doc's high-adventure Dictionary List of all Doc Savage Books Theme & Characters of each adventure 1 archived at http://www.stealthskater.com/DocSavage.htm Doc Savage: #000A - "the Doc Savage Authors" Introduction Just under 2 years after "The Shadow" appeared on magazine racks, Doc Savage became the 3rd pulp character to get his own magazine. The World met the 'Man of Bronze' in a novel titled The Man of Bronze (#001), March 1933. "Doc Savage" was created by Street&Smith’s Henry W. Ralston -- with help from editor John L. Nanovic -- in order to capitalize on the surprise success of "The Shadow" magazine. It was Lester Dent, though, who crafted the character into the superman that he became. Dent -- who wrote most of the adventures -- described his hero Clark “Doc” Savage Jr. as a cross between “Sherlock Holmes with his deducting ability, Tarzan of the Apes with his towering physique and muscular ability, Craig Kennedy with his scientific knowledge, and Abraham Lincoln with his Christ-liness.” Through 181 novels, the fight against Evil was on. -

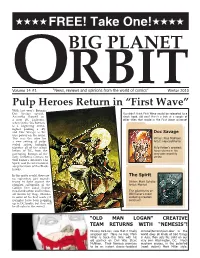

FREE! Take One!

FREE! Take One! Volume 14 #1 “News, reviews and opinions from the world of comics” Winter 2010 Pulp Heroes Return in “First Wave” With last year’s Batman/ Doc Savage special, You didn’t think First Wave would be relegated to a Azzarello showed us single book, did you? Here’s a look at a couple of a new DC Universe, other titles that reside in the First Wave universe! where in the ‘20s Batman is a beginning crime- fighter packing a .45, and Doc Savage is the Doc Savage true power on the scene. This was the intro for Writer: Paul Malmont a new setting of pulp- Artist: Howard Porter styled action, bringing together all of the action Pulp fiction’s greatest heroes of DC, from the hero returns in his gun-toting Batman of the very own monthly early Detective Comics, to series! Will Eisner’s detective The Spirit, and the international ace pilot team of the Black- hawks. In this gritty world, there are The Spirit no supermen, just mortals trying to fight against the Writer: Mark Schultz rampant corruption of the Artist: Moritat Golden Tree cabal. Expect two-fisted action and heroics, The adventures of all drawn by Rags Morales Will Eisner’s most in some of his best work yet enduring creation (samples have been popping continue! up in DC books, but they will be all-color in the series!) “OLD MAN LOGAN” CREATIVE TEAM RETURNS WITH “NEMESIS”! Missing Kick-Ass, now that it finally criminal/terrorist/evil-doer in the wrapped up? Have no fear, Mark world does all kinds of bad things Millar is back--this time with his in Asia, then sets his sight on our old partner on Civil War, Steve very own Washington, DC. -

Popular Culture Association - Pulp Studies Area

H-Announce Popular Culture Association - Pulp Studies Area Announcement published by Jason Ray Carney on Wednesday, September 23, 2020 Type: Conference Date: June 6, 2021 Location: United States Subject Fields: American History / Studies, Cultural History / Studies, Humanities, Literature, Popular Culture Studies POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATON -- PULP STUDIES AREA Pulp magazines were a series of mostly English-language, predominantly American, magazines printed on rough pulp paper. They were often illustrated with highly stylized, full-page cover art and numerous line art illustrations of the fictional content. They were sold at a price the working classes could afford, though they were popular with all classes. The earlier magazines, such asAll-Story , were general fiction magazines, though later they diversified and helped solidify many of the genres we are familiar with today, including western, detective, science fiction, fantasy, horror, romance, and sports fiction. The first pulp, Argosy, began life as the children’s magazine, The Golden Argosy, dated December 2nd, 1882 and the last of the “original” pulps was Ranch Romances and Adventures, November of 1971. Despite the limited historical range of the pulpwood magazine form, the “pulp aesthetic” continues to influence popular culture today. With this in mind, we are calling for presentations for the National PCA/ACA Conference that discuss the pulps and their legacy. Magazines: Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, Wonder Stories, Fight Stories, All-Story, Argosy, Thrilling Wonder Stories, Spicy Detective, Ranch Romances and Adventures, Oriental Stories/Magic Carpet Magazine, Love Story, Flying Aces, Black Mask, and Unknown, to name a few. Editors and Owners: Street and Smith (Argosy), Farnsworth Wright (Weird Tales), Hugo Gernsback (Amazing Stories), Mencken and Nathan (Black Mask), John Campbell (Astounding). -

A Pictorial History of Comic-Con

A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF COMIC-CON THE GOLDEN AGE OF COMIC-CON The 1970s were the formative years of Comic-Con. After finding its home in the El Cortez Hotel in downtown San Diego, the event continued to grow and prosper and build a national following. COMIC-CON 50 www.comic-con.org 1 OPPOSITE PAGE:A flier for the Mini-Con; the program schedule for the event. THIS PAGE: The Program Book featured a pre-printed cover of Balboa Park; photos from the Mini-Con, which were published in the Program Book for the first three-day MINI-CON Comic-Con held in August (clockwise MINI-CON from left): Forry Ackerman speaking; Mike Royer with some of his art; Comic-Con founding committee member Richard Alf NOTABLE MARCH 21, 1970 at his table; Ackerman at a panel discus- sion and with a fan; and Royer sketching GUESTS live on stage. The basement of the U.S. Grant Hotel, Downtown San Diego Attendance: 100+ Officially known as “San Diego’s Golden State Comic-Minicon” (the hyphen in Minicon comes and goes), this one-day event was held in March to raise funds for the big show in August, and FORREST J ACKERMAN was actually the first-ever West Coast comic convention. Most Comic-Con’s first-ever guest was the popular editor of Famous of those on the organizing com- Monsters of Filmland, the favorite mittee were teenagers, with the movie magazine of many of the major exceptions of Shel Dorf (a fans of that era. He paid his own recent transplant from Detroit way and returned to Comic-Con who had organized the Triple numerous times over the years. -

Contemporary American Comic Book Collection, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft567nb3sc No online items Guide to the Contemporary American Comic Book Collection, ca. 1962 - ca. 1994PN6726 .C66 1962 Processed by Peter Whidden Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2002 ; revised 2020 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc PN6726 .C66 19621413 1 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Contemporary American Comic Book Collection Identifier/Call Number: PN6726 .C66 1962 Identifier/Call Number: 1413 Physical Description: 41 box(es)41 comic book boxes ; 28 x 38 cm.(ca. 6000 items) Date (inclusive): circa 1962 - circa 1994 Abstract: The collection consists of a selection of nearly 6000 issues from approximately 750 titles arranged into three basic components by publisher: DC Comics (268 titles); Marvel Comics (224 titles); and other publishers (280 titles from 72 publishers). Publication dates are principally from the early 1960's to the mid-1990's. Collection Scope and Content Summary The collection consists of a selection of nearly 6000 issues from approximately 750 titles arranged into three basic elements: DC Comics, Marvel Comics, and various other publishers. Publication dates are principally from the mid-1960's to the early 1990's. The first part covers DC titles (268 titles), the second part covers Marvel titles (224 titles), and the third part covers miscellaneous titles (280 titles, under 72 publishers). Parts one and two (DC and Marvel boxes) of the list are marked with box numbers. The contents of boxes listed in these parts matches the sequence of titles on the lists. -

The Man Who Shook the Earth

THE MAN WHO SHOOK THE EARTH A Doc Savage Adventure by Kenneth Robeson THE MAN WHO SHOOK THE EARTH Table of Contents THE MAN WHO SHOOK THE EARTH........................................................................................................1 A Doc Savage Adventure by Kenneth Robeson......................................................................................1 Chapter I. THE FAKE NEWSPAPERMAN...........................................................................................1 Chapter II. THE MYSTERIOUS JOHN ACRE......................................................................................8 Chapter III. THE GIRL AFRAID OF EARTHQUAKES....................................................................16 Chapter IV. MISS MAN−SNATCHER.................................................................................................25 Chapter V. THE EARTH−SHAKER’S TRAIL....................................................................................30 Chapter VI. THE MAN WHO COULDN’T TALK..............................................................................39 Chapter VII. MURDER TRICK............................................................................................................46 Chapter VIII. IN TERROR’S SHADOW..............................................................................................51 Chapter IX. MOVER OF MOUNTAINS..............................................................................................58 Chapter X. CUT WIRES CLEW...........................................................................................................67 -

From Pulp Hero to Superhero: Culture, Race, and Identity in American Popular Culture, 1900-1940 Julian C

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Faculty Publications 10-2008 From Pulp Hero to Superhero: Culture, Race, and Identity in American Popular Culture, 1900-1940 Julian C. Chambliss Rollins College, [email protected] William L. Svitavsky Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_facpub Part of the American Popular Culture Commons Published In Chambliss, Julian C., and William Svitavsky. 2008. From pulp hero to superhero: Culture, race, and identity in american popular culture, 1900-1940. Studies in American Culture 30 (1) (October 2008). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Pulp Hero to Superhero: Culture, Race, and Identity in American Popular Culture, 1900-1940 Adventure characters in the pulp magazines and comic books of the early twentieth century reflected development in the ongoing American fascination with heroic figures. 1 As the United States declared the frontier closed, established icons such as the cowboy became disconnected from everyday American experience and were supplanted by new popular adventure fantasies with heroes whose adventures stylized the struggle of the American everyman with a modern industrialized, heterogeneous world. The challenges posed by an urbanizing society to traditional masculinity, threatened to a weaken men’s physical and mental form and to disrupt the United States’ vigorous transformation from uncivilized frontier to modern society.2 Many middle-class social commentators embraced modern industrialization while warning against “sexless” reformers who sought to constrain modern society’s excesses through regulations design to prevent social exploitation, environmental spoilage, and urban disorder. -

New Pulp-Related Books and Periodicals Available from Michael Chomko for October 2007

New pulp-related books and periodicals available from Michael Chomko for October 2007 As mentioned in my September list, I shipped a ton of books during the second week of September. Almost every regular customer received something or other from me. Our house is now quiet, with both kids off at college. My wife and I will be away from home beginning 10/4, celebrating our 29 th anniversary. We’ll be vacationing in Nova Scotia until 10/14. So if you write during that time, you won’t receive your answer until after the middle of the month. There are several pulp-related book shows coming up in the next few months. Gary Lovisi’s 19th Annual NYC Collectable Paperback & Pulp Fiction Expo will be held on Sunday October 7, 2007 at the Holiday Inn, 440 West 57th Street, New York City. For further information, please visit the Gryphon Book’s website at http://www.gryphonbooks.com/ . On Saturday and Sunday, October 20-21, in LaPlata, MO, the second annual DocCon will take place. Held in the hometown of Lester Dent, the creator of Doc Savage, the convention will feature a tour of the author’s home, a sneak preview of the Lester Dent Museum of Pulp History, special guests Anthony Tollin, current publisher of Doc and The Shadow, and Dr. Peter Koogan, a Wold Newton expert, and more. There are no membership fees, dealer fees, or anything of that nature. For further information, please visit the convention website at http://www.freewebs.com/doccon2/index.htm . On Saturday, November 3, 2007, Rich Harvey’s seventh annual Pulp Adventurecon will be held at the Ramada Inn, 1083 Rte 206 North, Bordentown, NJ. -

Zorro Visible Fictions

HOT Season for Young People 2011-2012 Teacher Guidebook Zorro Visible Fictions tson ber Ro las ug Do y b to ho P Season Sponsor A note from our Sponsor ~ Regions Bank ~ Jim Schmitz Executive Vice President Area Executive Middle Tennessee Area For over 125 years Regions has been proud to be a part of the Middle Tennessee community, growing and thriving as our area has. From the opening of our doors on September 1, 1883, we have committed to this community and our customers. One area that we are strongly committed to is the education of our students. We are proud to support TPAC’s Humanities Outreach in Tennessee Program. What an important sponsorship this is – reaching over 25,000 students and teachers – some students would never see a performing arts production with- out this program. Regions continues to reinforce its commitment to the communities it serves and in ad- dition to supporting programs such as HOT, we have close to 200 associates teaching financial literacy in classrooms this year. Season Sponsor Thank you, teachers, for giving your students this wonderful opportunity. They will certainly enjoy the experience. You are creating memories of a life- time, and Regions is proud to be able to help make this opportunity possible. Did you know that Krispy Kreme Doughnut Corporation helped groups across the nation raise more than $30 Million last year? Krispy Kreme’s Fundraising program is fast, easy, extremely profitable! But most importantly, it is FUN! For more information about how Krispy Kreme can help your group raise some dough, visit krispykreme.com or call a Neighborhood Shop near you! Contents Synopsis pages 2-3 The Author page 4 Historic Setting page 5 Comic Book Influence page 6 Exploration One page 7 Custom Crusader Exploration Two pages 8-9 A Horse, of Course Exploration Three page 10 The Play’s the Thing Exploration Four page 11 Destined for Greatness Exploration Five page 12 How Do You Find Bravery? TPAC Guidebook written and compiled by Lattie Brown with excerpts from the Zorro - Study Guide by Visible Fictions, as noted.