4 Robotics/AI in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Timeline Industrial Robots 2010-1959

Development Timeline Industrial Robots 2010-1959 2010 KUKA (Germany) launched a new series of shelf-mounted robots (Quantec) with a new controller KR C4 The Quantec K robots have an extremely low base, allowing a greater lower reach for unloading applications. The new KR C4 controller generation is the first to combine the complete safety controller in a single control system. This allows all tasks to be carried out at once. 2009 ABB, Sweden, launched the smallest multipurpose industrial robot, IRB120 ABB's smallest ever multipurpose industrial robot weighs just 25kg and can handle a payload of 3kg (4kg for vertical wrist) with a reach of 580mm. 2009 Yaskawa Motoman, Japan, introduces control system to sync up to 8 robots Yaskawa Motoman, Japan, introduced the improved robot control system (DX100) which provided the fully synchronized control of eight robots, up to 72 axis. I/O devices and communication protocols. Dynamic interference zones protect robot arm and provide advanced collision avoidance. 2008 FANUC, Japan, launched a new heavy duty robot with a payload of almost 1,200 kg "The M-2000iA is the world's largest and strongest six-axis robot," said Rich Meyer, product manager, Fanuc Robotics . "It has the longest reach and the strongest wrist surpassing all other six-axis robots available today. The wrist strength sets a record, but more importantly, allows our customers to move large heavy parts a great distance with maximum stability." 2007 With the first systems realized in 2006, Reis Robotics became market leader for photovoltaic -

Exhibition Guide

The Robot Revolution Has BegunBegun - Toward Heartwarming Society Society Exhibition Guide Date Nov. 29(Wed) Dec. 2(Sat), 2017 Venue Tokyo Big Sight East Hall Organizers: Japan Robot Association (JARA), THE NIKKAN KOGYO SHIMBUN, LTD. A4_17iREX_annai_E.indd 2 2017/02/20 14:04:13 Greeting RT The Robot Revolution Has Begun Robot Technology - Toward Heartwarming Society Robot technology has greatly contributed to the development of manufacturing in Japan, expanding its scope of application from production sites to our daily lives while continuing the challenge to address various issues, such as the declining birthrate and aging population, decrepit infrastructure and disaster response. The International Robot Exhibition 2017 will be held under the theme, “The Robot Revolution Has Begun –Toward Heartwarming Society-” with an aspiration to have people and robots coexist and collaborate in order to create a more people-friendly society. The latest robot technology and products from Japan and abroad will be presented during the exhibition together with next-generation technology such as AI, big data, and networks to facilitate more exchanges in technology and business talks. We hope that you will take this opportunity to participate in the exhibition. Japan Robot Association (JARA) © UDAGAWA YASUHITO 1998 THE NIKKAN KOGYO SHIMBUN, LTD. Features of the International Robot Exhibition One of the World’s Largest Robot Trade Shows The International Robot Exhibition first held in 1974, has since been held once every two years and will mark its 22nd exhibition this year. In the last exhibition held in 2015, the number of exhibitors was 446 companies and organizations, and the number of booths reached 1,882 which is the largest number ever. -

Robots May Storm World—But First, Soccer*

Robots May Storm World—But First, Soccer* By Mikiko Miyakawa The Daily Yomiuri (Tokyo), January 1, 2003 Robots pose no threat to Ronaldo—yet. But in 2050, a soccer team of human- oid robots may be able to beat the human World Cup champion team. Chasing this seemingly reckless goal, a group of Japanese scientists in 1997 launched RoboCup, the robotic soccer world championship. From these humble beginnings, the annual event has exceeded the organizers’ initial expectations. “The project started with 31 teams from 10 countries, but it rose to as many as 200 from 30 countries in 2002,” said RoboCup Federation President Minoru Asada, a professor at Osaka University. But as well as seeing the size of the event blossom, organizers—and the field of robot research—have seen dramatic developments in robotics, such as the omnidirectional vision and movement that enables robot players to see and move around the pitch much more efficiently. In June last year, while Japan and South Korea were busy cohosting the human soccer World Cup finals, RoboCup 2002 also was held in the two countries, in the cities of Fukuoka and Pusan. The robot players competed in four leagues—small, midsize, Sony four-legged (Aibo) and humanoid. The event also featured simulated soccer, rescue competi- tions and the RoboCup Junior competition for children. But the crowd favorites were the Aibo and humanoid leagues, Asada said. In the Aibo league, some of the robot dogs actually celebrated their teammates’ goals by standing on their hind legs—a sign of communication between the ro- bots. -

From: ATIP System PM 1997, Tokyo

From: ATIP System Account Sent: 1/13/1998 6:59:33 PM Subject: AT1P98.004 : International Robot Exhibition 1997, Tokyo ASIAN TECHNOLOGY INFORMATION PROGRAM (ATIP) REPORT: AT1P98.004 : International Robot Exhibition 1997, Tokyo To: Distribution From: [email protected] This is file name "atip9B.oo4" Date: 13 Jan 1998 AT1P98.004 : International Robot Exhibition 1997, Tokyo ABSTRACT: This report summarizes the 1997 Japan International Robot Exhibition held in Tokyo, Japan from October 28 to 31, 1997 at the Tokyo International Exhibition Center (Tokyo Big Sight, Ariake). The report provides information and comments on some of the main exhibits at the exhibition. zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzSTAßTOF REPORT ATlP9B.oo4========== Copyright (c) 1998 by the Asian Technology Information Program (ATIP) This material may not be published, modified or otherwise redistributed in whole or part, in any form, without prior approval by ATIP, which reserves all rights. International Robot Exhibition 1997, October 28-31, 1997, Tokyo, Japan (S.E.Lim/ATIP Tokyo) CONTENTS CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW 2. SCOPE OF EXHIBITS 3. MAIN EXHIBITORS 3. 1 . Conventional Industrial Robots and Applications Video Clip: PAIO Video Clip: Tescon Video Clip: YKSSOH Video Clip: CARRYBOY 3.2. Special Robots and Applications Video Clip: Nachi TR6OO Video Clip: Hephaist F6 Series Combination Stage 3.3. Related Equipment and Robot Accessories 3.3.1. Simulation and Off-line Programming Tools 3.3.2. Robot Accessories 3.3.3. Related Equipment 3.4 Research and Development in Robotics Figure 1. Honda Robot Figure 2. Sony Robot Finure 3 Tnkvu Rnbnt 1. BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW The Japan International Robot Exhibition is held biennially since 1974. -

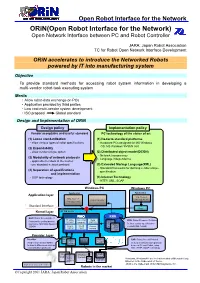

Orin(Open Robot Interface for the Network)の概要

Open Robot Interface for the Network ORiN(Open Robot Interface for the Network) Open Network Interface between PC and Robot Controller JARA: Japan Robot Association TC for Robot Open Network Interface Development ORiN accelerates to introduce the Networked Robots powered by IT into manufacturing system Objective To provide standard methods for accessing robot system information in developing a multi-vendor robot-task executing system Merits ・Allow robot-data exchange on PCs ・Application provided by third parties ・Low cost multi-vendor system development ・ISO proposal Global standard Design and Implementation of ORiN Design policy Implementation policy Vender acceptable and useful standard PC technology of the states of art (1) Loose standardization (1) De-facto standard platforms - allow various types of robot specifications - Hardware:PCs designed for MS Windows OS: MS Windows 95/98/NT4.0 (2) Expandability - allow vender unique option (2) Distributed object model(DCON) - Network transparency (3) Modularity of network protocols - Language independence - applicable to robots in the market - use standard network protocol (3) Extended Markup Language(XML) - Standard framework for defining vendor unique (4) Separation of specifications specification and implementation - OOP technology (4) Internet Technology - HTTP, XML, SOAP Windows PC Windows PC Application Application Application layer Mfg. System Mfg. System Motion Monitor management Management Standard Interface Proxy Kernel layer DCOM Server RAO RRD RAO: Robot Access Object Provider Correction Data RRD: Robot Resource Definition Provides the unified access mngmnt mngmnt caching B Co. Defines vendor specific robot method to robot data based on robotA Co. Async. Event models(XML format) DCON Access modelrobot control report logging model Provider layer Provider B Co. -

Irex2019 Post Show Report

Post Show Report The way towards a friendlier society, bridged by robots Date Dec. 18(Wed.)‒21(Sat.), 2019 Opening hours:10:00 to 17:00 Venue Tokyo Big Sight Aomi Halls, West Halls, South Halls Organizers Japan Robot Association (JARA) THE NIKKAN KOGYO SHIMBUN One of the largest robot trade shows in the world The newest robot technologies and products from Japan and around the world. We are pleased to inform you that thanks to your supports, International Robot Exhibition 2019 (iREX 2019), held from 18th to 21st December, came to an end with great success. The number of exhibiters this year was 637 and the number of booths was 3,060. This marks the largest number ever, breaking the record of previous iREX in 2017. As organizers, we would like to express our deep gratitude to all the exhibitors, related authorities, organizations and associations as this achievement would not be made if it were not for your warm supports. The contents and the brief report on iREX2019 are shown in the following pages for your reference. Thank you very much again, and we sincerely appreciate your continued supports. Japan Robot Association (JARA) THE NIKKAN KOGYO SHIMBUN, LTD. 1 Show Overview ■ Name INTERNATIONAL ROBOT EXHIBITION 2019 (iREX 2019) ■Theme “The way towards a friendlier society, bridged by robots” ■Purpose The purpose of the exhibition is to gather and exhibit industrial/service robots and related equipment from around the globe under one roof, to help improve the technology to use robots and market development, and to contribute to the creation of new markets and promotion of industrial technology of robots. -

Human Assistant Robotics in Japan

Human Assistant Robotics in Japan - Challenges and Opportunities for European Companies- Author: Dana Neumann Tokyo, March 2016 Acknowledgements I wish to thank Dr. Silviu Jora, General Manager (EU side) of the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation, and the Centre’s staff for the opportunity to be part of the MINERVA Fellowship Programme. I especially would like to thank all those (in Japan and the EU) who kindly offered me their assistance and expertise during my research. Dana Neumann [email protected] Tokyo, 30 March 2016 Disclaimer The information contained in this publication reflects the views of the author and not necessarily theviews of the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation, the views of the Commission of the European Union or Japanese authorities. While utmost care was taken to check and confirm all information used in this study, the author and the EU-Japan Centre may not be held responsible for any errors that might appear. © EU-Japan Centre for industrial Cooperation 2016 1 Table Of Contents 1 Executive Summary 5 2 Methodology 6 2.1 Information on general economic and political activities 6 2.2 Surveyed companies and research facilities 7 2.2.1 Main content of the questionnaire 7 2.3 Annotation 8 2.4 Area of observation and definition of “human assistant robotics” 8 3 Overview - The Market for Human Assistant Robotics 10 3.1 General global development 10 3.2 The Japanese market 11 3.3 RoboTech and nanotechnology 13 3.4 Expected technologies to be developed 15 4 Demographic Challenges and Resulting -

Robotic Solutions Fields of Lifestyle and Social Welfare, As Well As Public Services and Disaster Preparedness

NEDO TOPICS ® th Demonstration tests of the robotic suit “HAL ” Oct. 18 launched in Germany 2013. - Project by NEDO and the North Rhine-Westphalia Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy - No.50 NEDO and the North Rhine-Westphalia (1) (2) Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy began demonstration tests of a robotic medical device intended for a broad range of applications in clinical practice. The wearable robot “HAL®”, developed by CYBERDYNE Inc. as part of a NEDO Reporting on Today and Tomorrow’s Energy, Environmental and Industrial Technologies project, was introduced to a hospital in the city of Bochum, where tests have been conducted to demonstrate how the device could meet local medical needs. The hope is that public health insurance plans might cover the device and that its use might Featured Article (3) ® expand throughout Europe. (1) Robotic suit “HAL ” (2) A demonstration in Prior to the start of the demonstration Germany tests, Kenji Kurata, NEDO President, and (3) Dr. Kurata, NEDO Garrelt Duin, Minister for Economic President [left] and Mr. Duin, Minister for Affairs, Energy and Industry of the state Economic Affairs, of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, Energy and Industry Robotic signed a corresponding agreement for of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, demonstration in Bochum. sign the agreement Solutions Building a smart society with state-of-the-art technology New Enegy and Industrial Technology Development Organization NEDO is developing robotics technologies with the expectation of practical applications in the Robotic Solutions fields of lifestyle and social welfare, as well as public services and disaster preparedness. NEDO aims to realize a convenient and comfortable “smart society” where robots are active in various Building a smart society with state-of-the-art technology parts of our everyday lives in the near future. -

ATIP05.037: Robots at Aichi World Expo 2005

===================================================================== ASIAN TECHNOLOGY INFORMATION PROGRAM (ATIP) REPORT: ATIP05.037: Robots at Aichi World Expo 2005 To: Distribution From: [email protected] This is file name "atip05.037" Date: 28 July 2005 ATIP05.037: Robots at Aichi World Expo 2005 =====================START OF REPORT ATIP05.037===================== 0 Robots at Aichi World Expo 2005 ATIP/Japan Copyright (c) 2005 by the Asian Technology Information Program (ATIP) This material may not be published, modified or otherwise redistributed in whole or part, in any form, without prior approval by ATIP, which reserves all rights. ABSTRACT: This report is a summary of the various types of robots that were presented and are being used at the Aichi World Exposition 2005, an event taking place from March 25 to September 25, 2005 in Japan. KEYWORDS: Government Policy on Science and Technology, Regional Overview of Science and Technology, Robotics. COUNTRY: Japan DATE: 28 July 2005 REPORT CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2. PAST NEDO PROJECTS 3. WORKING ROBOTS 4. PROTOTYPE ROBOTS 4.1 TELEsarPHONE 4.2 EMIEW 4.3 Repliee Q1expo 4.4 UMRS-NBCT 4.5 MOIRA snake robot 4.6 IMR-Type 1 4.7 Applications of the HRP-2 4.8 WIND 4.9 Robovie Family 4.10 Nagara-3 1 4.11 Robot Suit HAL 4.12 Muscle Suit 5. CONCLUSION 6. CONTACTS & WEBLINKS 7. APPENDIX 1: PAST NEDO ROBOT PROJECTS 7.1 Robots for Hazardous Environments 7.2 HRP: Humanoid Robot Project 7.3 Creating Infrastructure Software to Serve as a Basis for Robot Development Work 8. APPENDIX 2: ROBOT PROJECTS ON DISPLAY AT AICHI 8.1 Working Robots 8.2 Prototype Robots 1. -

A Comparison of Websites by Robot Manufacturers in Germany and Japan: “The Ethical Relationship Between 'Robot' and 'Hum

Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies Vol. 7, March 2015, pp. 27–45 Doctoral Program in International and Advanced Japanese Studies Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Tsukuba http://japan.tsukuba.ac.jp/research/ Article A Comparison of Websites by Robot Manufacturers in Germany and Japan: “The Ethical Relationship Between ‘Robot’ and ‘Human Body’ as a Management Challenge” Martin POHL University of Tsukuba, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Associate Professor Beginning in science-fiction literature a century ago, the concept of robot today has become a technical reality. Industrial robots are mature and used in large scale – and the technicality of service robots is improving rapidly. This technical success made possible by competent management has in future to be safeguarded by integrating a balanced ethical relationship between ‘robot’ and ‘human body’ as an enlightened self-interest for enterprise. The analysis of Japanese and German companies based on companies’ web pages shows that progress in robots is a global phenomenon. The competition between robot-companies is a strong positive driver so that non-technical factors starting from R&D to production up to the delivery to the customer may play a crucial role in future: “ethics” as a management challenge in the context of the global robot markets may be an important success-factor for future robot-generations. Ongoing monitoring of the topic discussed is crucial — it is a joint task for management and science. Keywords: Robot, Ethics, Management, Japan, Germany Introduction Robots grow quickly to technical maturity and a number of resources were used during the recent decades to realize this success. -

Robotics-Pdf.Pdf

www.EUbusinessinJapan.eu Robotics in Japan January - 2015 Peter Van der Weeën Akoni KK EU-JAPAN CENTRE FOR INDUSTRIAL COOPERATION - Head office in Japan EU-JAPAN CENTRE FOR INDUSTRIAL COOPERATION - OFFICE in the EU Shirokane-Takanawa Station bldg 4F Rue Marie de Bourgogne, 52/2 1-27-6 Shirokane, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-0072, JAPAN B-1000 Brussels, BELGIUM Tel: +81 3 6408 0281 - Fax: +81 3 6408 0283 - [email protected] Tel : +32 2 282 0040 –Fax : +32 2 282 0045 - [email protected] http://www.eu-japan.eu / http://www.EUbusinessinJapan.eu / http://www.een-japan.eu www.EUbusinessinJapan.eu TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Market Analysis.................................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1. Market Overview and Key Segments...................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1. Market Size .................................................................................................................................................... 10 2.2. Industrial robots for the manufacturing industry................................................................................................. 13 2.2.1. Scope ............................................................................................................................................................. -

3 Digital Manufacturing (Robotics and 3D Printing) and the Evolution of Manufacturing in the Automotive Industry

Digital Disruption and the Transformation of Italian Manufacturing 3 Digital manufacturing (Robotics and 3D printing) and the evolution of manufacturing in the automotive industry This chapter explores the main markets for the production and use of robots and 3D printing and presents a comparative analysis of the core robotics and 3D printing competences in the major world digital manufacturing sectors. We focus specifically on Piemonte and its efforts to develop CPS in the automotive sector, a traditional key driver of Italian industrial development. Particular attention is paid to the role of collaborative robots compared to the more traditional manufacturing robots already used heavily in automotive production. The analysis is aimed at classifying robot technologies to understand why collaborative robots associated to sensors could revolutionize manufacturing production. The evolution of digital manufacturing and its rapid expansion are evident in many applications in the automotive value chain. The present review addresses some fundamental questions. For example, how has the automobile market changed in the most recent years? How are OEMs responding to the challenges posed by Industry 4.0? And what role can Italy (and Piemonte) play in this rapidly changing scenario? 3.1 Challenges to the Uptake of Digital Manufacturing Despite its far-reaching effects and current advances in the relevant technologies, digital manufacturing is in its infancy. One reason for this is the conservative business strategies and averseness to unproven production processes displayed by industry (Babiceanu & Chen, 2006; Leitão, 2009). For example , a survey of 300 manufacturing leaders, conducted by McKinsey & Company (2015), indicates that only around half (48%) of firms consider themselves prepared for the impact of Industry 4.0.