A Comparative Study of Catastrophic Health Expenditure in Zhejiang And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Refractive

Wang et al. BMC Ophthalmology (2021) 21:260 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-021-01996-2 RESEARCH Open Access Prevalence and risk factors of refractive error in Qinghai, China: a cross-sectional study in Han and Tibetan adults in Xining and surrounding areas Meng Wang†, Linyang Gan†, Jiantao Cui1, Guangliang Shan2, Ting Chen1, Xianghua Wang2, Yuhan Wang1, Li Pan2, Zhanquan Li3, Sen Cui3, Airong Yang3, Wenfang Li3, Guoqiang Jia3, Ximing Han3, Huijing He2, Yong Zhong1* and Jin Ma1* Abstract Background: Our study aimed to explore the prevalence and risk factors of refractive error (RE) in Han and Tibetan population aged 50–79 years in Xining and surrounding areas in Qinghai Province on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Methods: As part of the China National Health Survey, our cross-sectional study compared the age-adjusted prevalence of RE in Han and Tibetan older adults aged 50–79 years in Xining and surrounding areas. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to identify risk factors for myopia and hyperopia. Results: Among 769 Han participants and 476 Tibetan participants, the age-adjusted prevalence of myopia (spherical equivalent (SE) < − 0.5D), hyperopia (SE > + 0.5D), high myopia (SE < -6.0D) and astigmatism (cylindrical equivalent > = 0.5D) is 28.56, 22.82, 2.80, and 69.38%. Han participants have higher age-adjusted prevalence of myopia (32.93% vs 21.64%, p < 0.001), high myopia (3.93% vs 1.02%, p = 0.001) and astigmatism (72.14% vs 64.94%, p = 0.021) compared to Tibetan participants. Being Tibetan is the protective factor of myopia compared to being Han (OR 0.58, 95%CI 0.42–0.79, p < 0.001). -

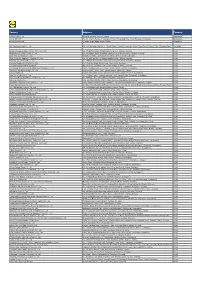

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Visa Application – Section 2.5 Detailing Mailing Addresses & Phone Numbers for Locations in China

Visa Application – Section 2.5 Detailing Mailing Addresses & Phone Numbers for Locations in China It is important to note that your travel arrangements are not finalized until you receive your official adoption itinerary. There is a chance that you will be staying at a different hotel than those included below. * = indicates a hotel that is specific to families adopting from the Gansu, Guangdong, Guizhou or Shaanxi province Holiday Inn Hefei Zugong Plaza Hotel (Anhui) (Gansu) 1104 Changjiang Dong Rd, No.543 Donggangxi Road, Hefei 230001 Chengguan District, Phone: 86-551-2206666 Lanzhou, Gansu, China 730000 Phone: 86931-881.9999 Sofitel Hefei Grand Park (Anhui) Mingyuan Xindu Hotel Fanhua Road, Hefei 230601 (Guangxi) Phone: 86-551-2216688 No. 38 Xinming Road, Nanning Phone: 86-771-2118988 Radisson BLU Hotel (Beijing) China Hotel Marriott No. A East Beishanhuan Road, (Guangzhou) Chao Yang District Liu Hua Road, Guangzhou 510015 Phone: 86-10-59223388 Phone: 86-20-86666888 Metro Park Lido Hotel* Novotel Guiyang Downtown (Beijing) (Guizhou) No. 6 Jiangtailu, Chaoyang District, No. 8, Zhanghua North Road Beijing, China 100004 Guiyang, Guizhou 550002 Phone: 8610-64376688 Phone: 86-851-858-1888 Howard Johnson Plaza Wanda Holiday-Inn (Chongqing) (Heilongjiang) International Trade Center, No. 90 Jinwei Road, No.66 Qingnian Rd, 400010 Harbin, 150010 Phone: 86-23-63666666 Phone: 86-451-84226611 JW Marriott Chongqing Crowne Plaza Hotel (Chongqing) (Henan) 77 Qing Nian Road, Yu Zhong District No.115 Jinshui Road, Chongqing Zhengzhou 450003 Phone: 86-23-63888888 Phone: 86-371-65950055 Lakeside Hotel Fengleyuan Hotel (Fujian) (Henan) No. 158 Hubing Road, Fuzhou 350003 North Nanyang Rd Phone: 86-591-87839888 Phone: 86-371-66771188 Hua Yang Plaza Hotel (Henan) No. -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

2021 First Quarterly Results

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 6030) 2021 FIRST QUARTERLY RESULTS This announcement is made pursuant to the disclosure obligations under Rule 13.09 of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Listing Rules”) and the Inside Information Provisions (as defined under the Listing Rules) under Part XIVA of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571 of the Laws of Hong Kong). The unaudited results of the Group for the first quarter ended 31 March 2021 are summarized as follows: • The Group recorded an operating revenue of RMB16,396,868,531.02; the net profit attributable to owners of the parent amounted to RMB5,164,799,333.48. • This report was prepared in accordance with the relevant disclosure requirements applicable to quarterly reports of listed companies issued by the China Securities Regulatory Commission. • The financial information contained in this report was prepared in accordance with the PRC GAAP. The contents of this report are consistent with the relevant announcement published by the Company on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. This -

Locating the Source of Message Diffusion in the Anonymous Network Ying-Shou ZHONG1, Nan-Fang LI2, Li-Li YANG3 and Xu WANG4,* 1No

2017 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Mechanical Automation (CSMA 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-506-3 Locating the Source of Message Diffusion in the Anonymous Network Ying-Shou ZHONG1, Nan-Fang LI2, Li-Li YANG3 and Xu WANG4,* 1No. 8, No. 54 West Road, Chengxi District, Xining City, Qinghai Province, China 2No. 8, No. 54 West Road, Chengxi District, Xining City, Qinghai Province, China 3No. 2 Jianyan Road, Xingtong Company, Xining City, Qinghai Province, China 4No. 89 Shengli Road, Xining City, Qinghai Province Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Keywords: Anonymous network, Network management, Message propagation model. Abstract. Locating the source of message diffusion in the anonymous network is vital for the network management and security. Existing works primarily focus on finding the disease propagation source in a normal network, few works have focused on tracing back the messages in an anonymous network. In this paper, we propose a method to enable us to identify the propagation source of the anonymous message. We are the first to use the message propagation model for the Crowds anonymous network. Based on the simulation study, we demonstrate that the effectiveness of our proposed method. Introduction Anonymous message helps people communicate privately with each other without disclosing their identities. In practice, several anonymous networks have been proposed, such as Crowds [1], Tor [2] and I2P [3] etc. Locating the message sender in the anonymous network is critical for network management and security. Researchers has demonstrated that through flow correlation [4,5] or website fingerprinting [6,7] attacks, the attacker can discover the message sender or the receiver in the anonymous network. -

20200227141213545.Pdf

Founded in 2007, SHAN SHUI Conservation Center is a Chinese NGO homegrown and dedicated to conservation practices. Together with our partners - communities, academic institutions, governments, companies, and media, we support local initiatives to defend the land we depend on. We focus our work on the most biologically diverse areas: Sanjiangyuan, the Mountains of Southwest China, and the Lancang River Basin. CONTENTS Nature Watch 22 Nature Watch Joint Action Base 23 The Chairman’s Foreword 01 Nature Watch Databases 24 The Executive Director’s Message 03 Nature Watch Data Application 25 Work Map 05 Snow Leopard Survey and Conservation Report 25 EIA Early Warning 25 Highlights 2018 07 An Urgent Call to Updat China Red 25 Lists (Fauna & Flora) Community-based Conservation 09 26 Snow Leopards and Grassland 10 Urban Biodiversity Recovery Snow Leopard Research and Conservation 11 Guilin Esquel Shi Ru Park 27 Wetland Research and Conservation 12 Beijing’s Urban Wetland Ecosystem 28 Sustainable Grassland Management 13 National Park Pilot Program 14 Communication and Fundraising 29 Communication 30 Giant Pandas and Forest 15 Fundraising Monitor and Patrol 16 31 Community Development 17 About Us 32 Policy Advocacy 18 Board Members 33 Forest Conservation and Recovery in Yunnan 19 Financial Overview 35 Yunlong : Multi-Value Forest Recovery 20 Staff and Awards 36 Menglian Heishan Initiative 21 Acknowledgments 37 Naren and Sayong Community Protected Areas 21 The Chairman's Foreword A March Through Uncertainty Since it was founded in 2007, Shanshui Conservation -

The Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of the Coordinated Development Of

2019 International Conference on Power, Energy, Environment and Material Science (PEEMS 2019) ISBN: 978-1-60595-669-5 The Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of the Coordinated Development of Urbanization and Resources Environmental Carrying Capacity in Lanzhou-Xining Urban Agglomeration Wei-ping ZHANG and Pei-ji SHI* School of Geography and Environmental Sciences, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou 730070, P.R. China *Corresponding author Keywords: Urbanization, Resource environmental carrying capacity, Coordination characteristics, Temporal and spatial patterns, Lanzhou-Xining urban agglomeration. Abstract. The coordination of urbanization and resources and environment is one of the key issues to promote regional social and economic development. This paper took Lanzhou-Xining urban agglomeration as the study area, constructed the evaluation index of urbanization and resource environmental carrying capacity first, and then used entropy method and the coordination degree model to measure the coordination of urbanization and resource environmental carrying capacity from 2005 to 2017. Results indicate that the overall index of urbanization and resource environmental carrying capacity of Lanzhou-Xining urban agglomeration shows an upward trend, and there are obvious spatial differences, especially between Lanzhou and Xining and the surrounding counties. The coordination degree of urbanization and resource environmental carrying capacity is between [0.5, 0.6), most of the counties are in a state of reluctance coordination, and the spatial distribution law of the degree is high in the east and low in the west. And the regional differences are gradually shrinking. There is a significant positive correlation between urbanization and capacity. The coordination status of Lanzhou and Xining provincial cities is relatively good, and the urbanization level is lower. -

The Case of Heyang Village

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4423–4442 1932–8036/20170005 The Political Economy and Cultural Politics of Rural Nostalgia in Xi-Era China: The Case of Heyang Village LINDA QIAN University of Oxford, UK This article offers a new theoretical framework to understand nostalgia as a political- economic and a cultural-political discourse in China. Introducing nostalgia as a “structure of feeling” in postreform China, the article analyzes its elevation as a new trope to address the economic and cultural contradictions of capitalistic global integration in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. It then traces the trickling down of nostalgia, from its initial invocation by Xi Jinping to its ideological propagation in major state- media productions and, finally, down to its appropriation and mobilization at the county and village levels. Finally, in grounding the research in Heyang Village, Zhejiang Province, the study demonstrates how, within this discourse of development with “nostalgia in mind,” a contentious enterprise of nostalgic tourism has figured as the centerpiece for rural development plans; Heyang’s future is now entangled in a contextually specific enterprise of the economy of nostalgia. Keywords: Chinese development, cultural heritage, nostalgia, rural tourism, Heyang In 2015, China Central Television’s (CCTV’s) annual Spring Festival Gala featured a song entitled Xiangchou 乡愁 (“Nostalgia”), which spoke of the bittersweet sense of nostalgic longing for the home village. Featured in the visual background were video clips of several villages in contemporary China, still deemed to possess “authentic” qualities of traditional Chinese village culture. CCTV initially shot these clips for the documentary series Jizhu Xiangchou (Nostalgia in Mind), which aired on CCTV-4 in the beginning of that same year. -

SUPPLIER LIST OCTOBER 2019 Cotton on Group - Supplier List 2

SUPPLIER LIST OCTOBER 2019 Cotton On Group - Supplier List _2 REGION SUPPLIER NAME FACTORY NAME SUPPLIER ADDRESS PRODUCT TOTAL % OF % OF % OF TYPE WORKERS FEMALE MIGRANT TEMP WORKERS WORKERS WORKERS BANGLADESH APTECH DESIGN LTD DESIGNER FASHION LTD GOHAILBARI SHIMULIA APPAREL 3422 72% 0% 0% SAVAR DHAKA BANGLADESH APTECH DESIGN LTD Y-FRONTS ACCESSORIES (NEW HOUSE 24, WARD # 01, ARSHINAGOR MAIN ROAD APPAREL 24 0% 0% 0% LOCATION) ARSHINAGOR, KERANIGONJ DHAKA BANGLADESH BELAMY TEXTILES LTD BELAMY TEXTILES LTD KHOWAZ NAGAR, AZIMPARA APPAREL KARNAFULLY CHITTAGONG BANGLADESH BIG BOSS CORPORATION LTD (of aptech BIG BOSS CORPORATION LTD (NEW) APTECH INDUSTRIAL PARK APPAREL group) 30 SHARABO,KASIMPUR GAZIPUR BANGLADESH CLASSIC FASHIONS FOUR DESIGN PVT LTD (NEW) PLOT NO. B-201, 202, BSCIC HOSIERY I/E APPAREL 305 64% 0% 0% SHASONGAON, ENAYETNAGAR, FATULLAH NARAYANGANJ BANGLADESH CLASSIC FASHIONS FOUR DESIGN PVT LTD (TEMPORARY) PLOT NO. B327/328, BSCIC HOSIERY I/E APPAREL 380 60% 0% 0% SHASONGAON, ENAYETNAGAR, FATULLAH NARAYANGANJ BANGLADESH IMPRESS NEWTEX COMPOSITE TEXTILES B2B EXCELLANCE LTD MIRZAPUR PURBAPARA, APPAREL 1355 76% 0% 0% LTD 8 NO. MIRZAPUR MOUZA, GAZIPUR SADAR,GAZIPUR BANGLADESH IMPRESS NEWTEX COMPOSITE TEXTILES IMPRESS NEWTEX COMPOSITE TEXTILES GORAI INDUSTRIAL AREA APPAREL 2124 56% 0% 0% LTD LTD MIRZAPUR TANGAIL BANGLADESH IRIS FABRICS LIMITED IRIS FABRICS LIMITED ZIRANIBAZAR APPAREL 2984 47% 0% 0% KASHIMPUT, JOYDEVPUR GAZIPUR BANGLADESH JERICHO IMEX JERICHO IMEX LTD MONTREE BARI ROAD APPAREL 700 62% 0% 0% SOUTH SHANLA, SHANLA BAZAR -

Producent Adres Land

*Deze lijst bevat alle 'non-food' leveranciers die producten aan Lidl hebben geleverd in de periode tussen 1 maart 2019 en 29 februari 2020. Producent Adres Land 3W Home Fashion Heyuan Co., Ltd. Mingzhu Industrial Park, Heyuan West Road, Chuangye South Road, Heyuan, Guangdong China A.B Sales Corp. (A Unit Of Satyam Creations (Pvt) Ltd.) Plot No. 1642, Zone -09, Kolkata Leather Complex, Bantala, 24 Parganas (South), Kolkatta, West Bengal India AB Apparels Ltd. No. 225 Singair Road, Tetuljhora, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Above & Beyond Co., Ltd. Plot No. 116/A, 116/B, Settmu (10) Street, Myay Taing Block No. 42, Industrial Zone (1), Shwe Pyi Thar Township, Yangon Myanmar Ador Composite Ltd. 1, C&B Bazar, Gilarchala, Sreepur, Gazipur, Bd Gazipur District, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Advanced Composite Textile Ltd. Kashor Masterbari, Bhaluka, Mymensingh, Sylhet Bangladesh Afroze Textile Industries (Pvt) Ltd. Plot C-8, Scheme 33, S.I.T.E., Super Highway, Karachi, Sindh Pakistan Afroze Textile Industries (Pvt) Ltd. LA-1/A, Block 22, F.B. Area, Karachi, Sindh Pakistan Ahmed Fashions 34/1, Darus Salam Road, Dhaka Bangladesh Ai Qi Fujian Shoes Plastic Co., Ltd. Meiling Street, Shuanggou Industrial District, Sichuan, Jinjiang, Fujian China Al Hadi Textile (Pvt) Ltd. D-12 Site Super Highway Industrial Area, Karachi, Sindh Pakistan Alpine Clothings Polpithigama (Pvt) Ltd. Andarayaya, Polpithigama Sri Lanka Alpine Clothings Yapahuwa (Pvt) Ltd. Anuradhapura Road, Uduweriya, North Western Sri Lanka AMG Factory Ltd. Plot No. 51 & 52, Myay Taing Block No. 25, Shwe Lin Ban Industrial Zone, Hlaing Thar Yar Township, Yangon Myanmar Andy Accessory Co., Ltd.