An Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Proto-Historic Settlements In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peon Fatehgarh.Pdf

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Peon (Service Group-D) reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre of Municipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./ disability Miss 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 191 Narinder Singh S/o Village Atta Pur, P.O. 26.03.1986 OH 45% Shambu Ram Charnarthal Kalan, Fatehgarh Sahib. 2 192 Gurjant Singh S/o Village Nariana, P.O. 20.05.1983 OH 60% Avtar Singh Bhagrana, Teh Bassi Pathana, Distt. Fatehgarh Sahib. 3 386 Gurwinder Singh S/o V.P.O Hallal Pur, Teh. 01.01.1991 OH 70% Sukhvinder Singh and Distt. Fatehgarh Sahib 4 411 Lakhwinder Singh Vill. Fateh Pur Araian, 04.02.1992 OH 85% S/o Meva Singh Teh. Basi Bathana, Distt.- Fateh Garh Sahib PB- 140412 5 501 Satpal Singh S/o V.P.O Malko Majra, Distt. 17.02.1981 OH 50% Hari Singh Fatehgarh Sahib 6 563 Balwant Singh S/o Village Dedrha, PO 20.12.1992 OH 70% Bahadur Singh Kumbadgarh, Fatehgarh Sahib 7 665 Narinder Singh S/o Vill. Dadiana, Teh. Bassi 05.10.1986 OH 100% Shamsher Singh Pathana, PO Rupalheri, District Fathegarh Sahib. 8 752 Tejvir Singh S/o W.No: 12, Amloh, Distt: 03.07.1990 OH 40% Chhajju Ram Fatehgarh Sahib. 9 885 Jagjit Singh S/o Vill. -

Geography of Early Historical Punjab

Geography of Early Historical Punjab Ardhendu Ray Chatra Ramai Pandit Mahavidyalaya Chatra, Bankura, West Bengal The present paper is an attempt to study the historical geography of Punjab. It surveys previous research, assesses the emerging new directions in historical geography of Punjab, and attempts to understand how archaeological data provides new insights in this field. Trade routes, urbanization, and interactions in early Punjab through material culture are accounted for as significant factors in the overall development of historical and geographical processes. Introduction It has aptly been remarked that for an intelligent study of the history of a country, a thorough knowledge of its geography is crucial. Richard Hakluyt exclaimed long ago that “geography and chronology are the sun and moon, the right eye and left eye of all history.”1 The evolution of Indian history and culture cannot be rightly understood without a proper appreciation of the geographical factors involved. Ancient Indian historical geography begins with the writings of topographical identifications of sites mentioned in the literature and inscriptions. These were works on geographical issues starting from first quarter of the nineteenth century. In order to get a clear understanding of the subject matter, now we are studying them in different categories of historical geography based on text, inscriptions etc., and also regional geography, cultural geography and so on. Historical Background The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the 2 JSPS 24:1&2 rivers Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Chenab and Jhelum. -

Police Department District Mansa Chart of PO's U/S 82-83 Cr. P.C. for the Month up to Date 20-01-2021 Sr.No Name of Police St

Police Department District Mansa Chart of PO's u/s 82-83 Cr. P.C. for the Month UP TO Date 31-08-2021 Sr.no Name of Pos New Pos Arrest Pos Died/ Balance According Double Police Station beginning during the during the Canceled to Police Entry the month month month Pos Station 1 City 1 Mansa 20 - - - 20 20 - 2 City 2 mansa 09 - - - 09 09 3 Sadar Mansa 13 - - - 13 13 - 4 Joga 8 - - - 8 10 2 5 Bhikhi 13 - - - 13 13 - 6 City Budhlada 17 - - - 17 18 1 7 Sadar 2 - - - 2 2 - Budhlada 8 Bareta 5 - - - 5 5 - 9 Boha 5 - - - 5 6 1 10 Sardulgarh 5 - - - 5 6 1 11 Jhunir 13 - 2 - 11 11 - 12 Jaurkian 10 - - - 10 12 2 Total 120 0 2 0 118 125 7 PS City-1, Mansa Sr. Name & Particulars of Pos’ Complete address FIRNo. Date, U/S & PS Name of court No. Residing PS & District & date of declare Pos 1 Bhag Singh s/o Hajoora Singh Jat r/o Khiwa Kalan 70 dt. 6/11/90 u/s 304 IPC PS City-1, Mansa SDJM Mansa PS Bhikhi Distt. Mansa 19/7/1991 2 Raj Kumar s/o Das Ram Jassal Abadpur Mohalla 409 dt. 21/8/1981 u/s 409 IPC PS City-1 Mansa SDJM Mansa PS Jalandhar District Jalandhar 29/05/1982 3 Bhammar Lal Lodha s/o Ladhu Lal M/s Minakshi 27 dt. 14/02/97 u/s 420 IPC PS City-1 Mansa CJM Mansa Cotton Corporation Kikkar Bazar PS Kotwali 6/4/1998 District Bathinda 4 Rajan Bansal s/o Karishan Bansal Sawavan Colony 196 dt. -

List of Sewa Kendras Retained

List 2 - List of Sewa Kendras Retained List 2 - List of Sewa Kendras Retained S No District Sewa Kendra Name and Location Center Code Type 1 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, HO, Kitchlu Chownk PB-049-00255-U025 Type-I 2 Amritsar MC Majitha Near Telephone Exchange PB-049-00255-U001 Type-II 3 Amritsar MC Jandiala Near Bus Stand PB-049-00255-U002 Type-II 4 Amritsar Chamrang Road (Park) PB-049-00255-U004 Type-II 5 Amritsar Gurnam Nagar/Sakatri Bagh PB-049-00255-U008 Type-II 6 Amritsar Lahori Gate PB-049-00255-U011 Type-II 7 Amritsar Kot Moti Ram PB-049-00255-U015 Type-II 8 Amritsar Zone No 6 - Basant Park, Basant Avenue PB-049-00255-U017 Type-II Zone No 7 - PWD (B&R) Office Opp. 9 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U019 Type-II Celebration Mall 10 Amritsar Zone No 8- Japani Mill (Park), Chherata PB-049-00255-U023 Type-II Suwidha Centre, DTO Office, Ram Tirath 11 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U026 Type-II Road, Asr 12 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Ajnala PB-049-00255-U028 Type-II Suwidha Centre, Batala Road, Baba 13 Amritsar PB-049-00255-U029 Type-II Bakala Sahib 14 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Attari PB-049-00255-U031 Type-II 15 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Lopoke PB-049-00255-U032 Type-II 16 Amritsar Suwidha Centre, Tarsikka PB-049-00255-U034 Type-II 17 Amritsar Ajnala PB-049-00255-R001 Type-II 18 Amritsar Ramdass PB-049-00255-R002 Type-III 19 Amritsar Rajasansi PB-049-00259-R003 Type-II 20 Amritsar Market Committee Rayya Office PB-049-00259-R005 Type-II 21 Amritsar Jhander PB-049-00255-R025 Type-III 22 Amritsar Chogawan PB-049-00255-R027 Type-III 23 Amritsar Jasrur PB-049-00255-R035 -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Of Dr. R.S. Bisht Joint Director General (Retd.) Archaeological Survey of India & Padma Shri Awardee, 2013 Address: 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad, Ghaziabad – 201005 (U.P.) Tel: 0120-3260196; Mob: 09990076074 Email: [email protected] i Contents Pages 1. Personal Data 1-2 2. Excavations & Research 3-4 3. Conservation of Monuments 5 4. Museum Activities 6-7 5. Teaching & Training 8 6. Research Publications 9-12 7. A Few Important Research papers presented 13-14 at Seminars and Conferences 8. Prestigious Lectures and Addresses 15-19 9. Memorial Lectures 20 10. Foreign Countries and Places Visited 21-22 11. Members on Academic and other Committees 23-24 12. Setting up of the Sarasvati Heritage Project 25 13. Awards received 26-28 ii CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Data Name : DR. RAVINDRA SINGH BISHT Father's Name : Lt. Shri L. S. Bisht Date of Birth : 2nd January 1944 Nationality : Indian by birth Permanent Address : 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad Ghaziabad – 201 005 (U.P.) Academic Qualifications Degree Subject University/ Institution Year M.A . Ancient Indian History and Lucknow University, 1965. Culture, PGDA , Prehistory, Protohistory, School of Archaeology 1967 Historical archaeology, Conservation (Archl. Survey of India) of Monuments, Chemical cleaning & preservation, Museum methods, Antiquarian laws, Survey, Photography & Drawing Ph. D. Emerging Perspectives of Kumaun University 2002. the Harappan Civilization in the Light of Recent Excavations at Banawali and Dholavira Visharad Hindi Litt., Sanskrit, : Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Prayag 1958 Sahityaratna, Hindi Litt. -do- 1960 1 Professional Experience 35 years’ experience in Archaeological Research, Conservation & Environmental Development of National Monuments and Administration, etc. -

STATE SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY Punjabi University, Patiala

STATE SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY Punjabi University, Patiala Draft Social Impact Assessment Report & Draft Social Impact Management Plan of Land Acquisition for completion of 100 feet wide road in mega project in area of New Chandigarh at Village Mastgarh S.A.S. Nagar. Submitted to: Department of Housing and Urban Development, Government of Punjab, Chandigarh November 2019 STATE SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY, PUNJABI UNIVERSITY PATIALA Contents Topic Page No. Introduction 1-15 Team Composition, Approach, Methodology and Schedule 16-21 of SIA Land Assessment 22-28 Socio-Economic and Cultural Profile of Affected Area 29-31 Social Impacts 32-37 Analysis of Costs and Benefits 38-40 Social Impact Management Plan 41-44 Annexure I 46 Questionnaire 52 STATE SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY, PUNJABI UNIVERSITY PATIALA INTRODUCTION I. Context and the Background The present study “Social Impact Assessment study of Land Acquisition for completion of 100 feet wide road in mega project in area of New Chandigarh at Village Mastgarh S.A.S. Nagar. Urbanisation ‘Urban’ area means the area with limited geographical area, inhabited by a largely and closely settled population, having many common interests and institutions, under a local government authorised by the State. Urbanization is a shift from rural to urban areas, the gradual increase in the proportion of people living in urban areas and the ways in which each society adapts to the change. The growth of urban centers is a result of multiple factors such as industrialization, economic causes, education and many more pull & push factors. Table 2.1: Data on Urbanization Increase in Decadal Population Urban Population Growth (2001 to 2011) Punjab S.A.S Nagar S.A.S India Punjab Rural Urban Nagar 32.08 31.16 37.49 55.17 7.58 25.72 Source: Census 2011 1 STATE SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY, PUNJABI UNIVERSITY PATIALA Figure 2.1: Density of Population in India Source: Urbanization in India: Population and Urban Classification Grids for 2011 by Deborah Balk, Mark R. -

LIST of APPLICATION RECEIVED in THIS FOFICE for the POST of TUBEWELL OPERATOR for S.C CATEGORY Sr. No. Diary No. and Date Name

LIST OF APPLICATION RECEIVED IN THIS FOFICE FOR THE POST OF TUBEWELL OPERATOR FOR S.C CATEGORY Sr. Diary No. and Name of the Father’s Date of Residence address Qualification Marks Percenta Experience Remarks No. date Applicant Name Birth obtained/ ge % Sarv/Shir Sarv/Shri total marks 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 02 Ravi Kant Jeet Ram 02.12.1978 H.No.595-G-Block Nangal Dam B.A ARTS ITI 187/300 62.33% No Exp. Not Eligible 14.10.2013 DT.Ropar-140724 STENO in ITI Steno 2 07 Sarabjeet Singh Narang Singh 10.8.1981 # 208 Village Khuda Alisher,U.T 10 pass - - No Exp. Not Eligible Dt:15.10.2013 Chd 3 06 Gursharan Singh Makhan 9.12.1990 Village Chapra P.O Lehal Teh 10+2 ITI 434/775 56% No Exp. Not Eligible Dt:15.10.2013 Singh Distt.Ludhiana Electronics and Communication. 4 05 Kamalpreet Singh Jaspal Singh 4.7.1994 Village Sawara Post office Landran 10+2, - - No Exp. Not Eligible due DT:15.10.2013 Distt.Mohali to Non ITI 5 04 Lakhwinder Singh Balbir Singh 15.10.1985 Village Bhanri Distt.Patiala 10+2, - - No Exp. Not Eligible due Dt:15.10.2013 Teh Patiala P.O. Nazirpur to Non ITI 6 03 Raj Pal Singh Balwant 21.09.1990 V.P.OLauli Distt.and The Patiala 10+2, - - No Exp. Not Eligible due Dt:15.10.2013 Singh to Non ITI 7 15 Ramandeep Balkar Chand 28.08.1988 H.No D3/1771 Gali No.11 Ram 10+2 and ITI in 532/700 76% No Exp. -

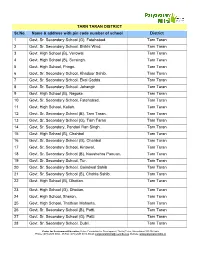

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Information Manual for Rti Act, 2005 District & Sessions Court, Rupnagar

INFORMATION MANUAL FOR RTI ACT, 2005 DISTRICT & SESSIONS COURT, RUPNAGAR PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICER CONTACT DETAILS Sr. No. PIO's Name / Designation Phone / Fax No. DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE,RUPNAGAR 1 Appellate Authority Ms. Harpreet Kaur Jeewan, District & Sessions 01881-223001 Judge 0164-223102(fax) 2 Public Information Officer Sh. Jarnail Singh, Superintendent / CAO 01881-223001 0164-223102(fax) CIVIL JUDGE SENIOR DIVISION, RUPNAGAR 1 Appellate Authority Sh. Madan Lal, Civil Judge (Senior Division) 01881-223005 2 Public Information Officer Clerk of Court ( COC ) CHIEF JUDICIAL MEGISTRATE,RUPNAGAR 1 Appellate Authority Ms. Pooja Andotra, Chief Judicial Magistrate 01881- 223003 2 Public Information Officer Clerk of Court ( COC ) CONTENTS OF MANUALS: MANUAL- I Particulars of Organization MANUAL-II The Power and Duties of its Officers and Employees MANUAL- III The Procedure Followed In the Decision Making MANUAL-IV The Norms Set By It for the Discharge of Its Functions MANUAL- V The Rules, Regulations, Instructions, Manual and records, held by it 1 | P a ge MANUAL- VI Statement Of The categories of Documents held by it etc. MANUAL- VII The particular of formulation of it policy or implementation MANUAL- VIII A Statement of the Boards, Councils, Committees etc. MANUAL- IX Directory of Its Officers and Employees MANUAL- X Monthly Remuneration Received MANUAL- XI The Budget Allocation MANUAL- XII The manner of execution of subsidy programs etc. MANUALXIII Particulars of concessions, permits or authorizations etc. MANUAL – XIV Details in respect of the information, available to or held by it, reduced in an electronic form MANUAL- XV The particulars of facilities available to citizen etc. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Kapurthala, Part X-A & B, Series-17, Punjab

CENSUS 1971 PARTS X-A & B VILLAGE & TOWN SERIES 17 DIRECTORY PUNJAB VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT CENSUS KAPURTHALA HANDBOOK DISTRICT P. L. SONDHI H. S. KWATRA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE OF THE PUNJAB CIVil, SERVICE Ex-Officio Director of Census Opemtions Deputy Director of Census Opemtions PUNJAB PUNJAB Motif-- GURDWARA BER SAHIB, SULTANPUR LODHI Gurdwara Be?" Sahib is a renowned place of pilgrimage of the Sikhs. It is situated at Sultanpur Lodhi, 16 miles South of Kapurthala, around a constellation of other Gurdwaras (Sikh Temples) associated with the early life of Guru Nanak Dev. It is n:a,.med after the 'Ber', tree under which Guru Nanak Dev used to meditate. Legend has it that sterile women beget child7'en after takinq leaves of this tree. The old Gu'rdwara was re-constructed by the joint effo'rts of Maharaja Jagatjit Singh of Kapurthala, Maharaja Yadvindra Singh of Patiala and Bhai Arjan Singh of Bagrian. A big fair is held at this Gurdwara on Guru Nanak Dev's birthday. Motif by : J. S. Gill. 15 '40' PUNJAB DISTRICT KAPURTHALA s· KILOIUTRES S o 5 10 15 20 4 8 12 MILES 4 o· 3 " Q TO JUL LlJNDllR <' ~O "'''<, U ""a". I. \.. u .) . 31 DISTRICT 80UNOARV..... POST' TtLEGftAPH OFfiCE "................. P'T TAHSIL BOUNDARY.. _TALlil PRIMARV HEALTH DISTRICT HEADQUARTERS .. CENTRE S IMATERNITY • CHIlD T"HSIL HEADQUARTERS. WELfARE CENTRES ............... - ... $ NATIONAL HIGHWAY .. liECONDARY SCHOOL./COl.LEGE .............•..• , OTHER METAI.LED ROAII.. 45 BROAD GAUGE RAILWAYS WITH STATIOfll. ... RS 4 RIVER .. - CANAL .. UklAII AREA •.. RUT HOUSE .... VILLAQES HAVING POPULATION 5000+ URBAN POPULATION " 50.000 PERSONS 10.000 •.. -

Proclaimed Offenders

Sheet2 LIST OF PROCLAIMED OFFENDERS Sr. Date of Date of CNR No. Case No. Case Title Particulars of P.O. FIR No. Date Under Section Police Station Court Name No. Instt. Order Om Parkash Village Dhakana Kalan 1 PBPTA10040742017 COMA/672/2017 09/05/17 Mahesh Kumar Vs Om Parkash NA 138 NA 17/08/18 Ms. Karandeep kaur JMIC Rajpura Tehsil Rajpura 1. SUNIL KUMAR H.NO. 381 GURU PARWINDER SINGH VS SUNIL ANGAD DEV COLONY RAJPURA 2. 2 PBPTA10009012015 COMA/438/2015 07/09/15 NA 138 NA 15/11/17 Ms. Karandeep kaur JMIC Rajpura KUMAR BHUPINDER KUMAR H.NO. 381 GURU ANGAD DEV COLONY RAJPURA ROHIT MUNJAL VS. NARESH NARESH KUMAR. 1539 NEAR MAHAVIR 3 PBPTA10027592017 COMA/480/2017 07/11/17 NA 138 NA 17/08/18 Sh. Abhinav kiran Sekhon ,JMIC, Rajpura KUMAR MANDIR WARD NO 22 RAJPURA Sukhdev Kumar New Dhiman Furniture 4 PBPT030007622018 COMA/329/2018 01/17/18 Vikas sood vs Sukhdev Kumar NA 138 NA 18/08/18 Ms. Neha Goel ,JMIC Patiala. Gaijukhera Rajpura STATE V/S NADEEM KHAN PS MANDI 13 GAMBLING P.S URBAN ESTATE 5 PBPT03-000966-2014 Cha/44/2014 02/11/14 171/2013 30/07/14 SH.RAMAN KUMAR,ACJM,PATIALA . NADEEM KAHN MUJAFARNAGAR U.P Act , PATIALA DHARMINDER SINGH @ MANGA S/O 336,427,419,420 CIVIL LINES 6 PBPT03-000586-2014 CHA/54/2014 7-6-2014 STATE VS PARDEEP KUMAR SURJIT SINGH R/O VILL NIJARA,DIST 305/16-11-13 8-7-2016 MS.NIDHI SAINI,JMIC,PATIALA. ,467,IPC PATIALA JALANDHAR RAJAT GARG S/O RAKESH GARG R/O CIVIL LINES 7 PBPT03002260-2017 CHI36/2017 5-4-2017 STATE VS NISHANT GARG 251/19-11-16 406,420 IPC 16-8-2018 MS.NIDHI SAINI,JMIC,PATIALA. -

Find Police Station

Sr.No. NAME OF THE POLICE E.MAIL I.D. OFFICIAL PHONE NO. STATION >> AMRITSAR – CITY 1. PS Div. A [email protected] 97811-30201 2. PS Div. B [email protected] 97811-30202 3. PS Div. C [email protected] 97811-30203 4. PS Div. D [email protected] 97811-30204 5. PS Div. E [email protected] 97811-30205 6. PS Civil Lines [email protected] 97811-30208 7. PS Sadar [email protected] 97811-30209 8. PS Islamabad [email protected] 97811-30210 9. PS Chheharta [email protected] 97811-30211 10. PS Sultanwind [email protected] 97811-30206 11. PS Gate Hakiman [email protected] 97811-30226 12. PS Cantonment [email protected] 97811-30237 13. PS Maqboolpura [email protected] 97811-30218 14. PS Women [email protected] 97811-30320 15. PS NRI [email protected] 99888-26066 16. PS Airport [email protected] 97811-30221 17. PS Verka [email protected] 9781130217 18. PS Majitha Road [email protected] 9781130241 19. PS Mohkampura [email protected] 9781230216 20. PS Ranjit Avenue [email protected] 9781130236 PS State Spl.